How Knitting Was Used By Spies During WWI And WWII

Subtle little wallflowers woven into the ambience of any given room — unsuspecting, unthreatening, undetectable. Whatever it took to protect shield your identity from foreign combatants was paramount to wartime spies on treacherous missions of reconnaissance. There's no trivializing the act of picking up a rifle and storming the battlefield alongside fellow soldiers, but walking straight into the lion's den truly is a whole other animal. Nonetheless, it had to be done, and without the help of spies over the past century of conflict, it's tough to say whether or not things would have turned out differently.

Spying on the enemy carried significant — and often fatal — risks. In World War I alone, 235 Allied spies were captured by German forces during their missions. Eavesdropping on conversations, codebreaking, and various other inconspicuous methods of silent infiltration were characteristic of spy tactics during both World Wars. Other double-agents opted for a more audacious position within enemy ranks. Mata Hari (Margaretha Zelle) was a revered belly dancer whose prowess and reputation were legendary amongst German soldiers. In 1914, when the French government commissioned her to gather secret information from a high-ranking enemy figure, her identity was tragically exposed after she passed along false information to that was intended as bait. She was found guilty by enemy captors and was executed three years later (via DK Find Out!). Scattered cases of misfortune were inevitable, but many others prevailed. One method of avoiding suspicion was particularly effective, though bizarre all the same: knitting.

Spies used knitting to translate codes

"Spies have been known to work code messages into knitting, embroidery, hooked rugs, etc.," A passage from "A Guide to Codes & Signals" (1942) reads. According to Atlas Obscura, women placed within a certain enemy environment where information was rich would use their knitting needles to transcribe messages into the fabric of whatever soft garment they were stitching together. One particular anecdote recounts an old woman who, while seated before an open window in the heart of Belgium, observed German trains passing. She'd use various stitches, bumps, and holes along the fabric line to indicate the number of trains that she observed racing by — almost like a rudimentary form of morse code. The translation would be understood by Allied executives and her correspondence would prove invaluable.

"I always carried knitting because my codes were on a piece of silk," famous British spy Phyllis Latour Doyle once shared while reflecting upon those harrowing years. "I had about 2000 I could use. When I used a code I would just pinprick it to indicate it had gone. I wrapped the piece of silk around a knitting needle and put it in a flat shoe lace which I used to tie my hair up." Doyle's work as a spy was exemplary of what military officials at the time called stenography, which was an unconventional way to deconstruct codes (per Atlas Obscura).

The art of stenography

Trains that often carried enemy soldiers, weapons, or resources were of significant interest to Allied forces. When a spy wanted to translate the number of trains she spotted passing, she'd indicate the figure using purls (an overlapping of yarn that forms a horizontal line). One purl indicated a certain kind of train while dropping a purl signified another (via Handwoven Magazine). Knit stitches — a type of stitch formed in a "v" shape — were incorporated in sequence with purls to construct cryptic messages. It was an elaborate system that managed to subvert detection most times, though things got tricky when the spy had to hand the garment off to a soldier (often a spy as well) who was acting as the messenger. If either were found out, execution was more or less imminent for both of them (per Atlas Obscura).

"I can remember being taken to the station and a female soldier made us take our clothes off to see if we were hiding anything," Phyllis Latour Doyle explained in a 2009 interview with New Zealand Army News. "She was looking suspiciously at my hair so I just pulled my lace off and shook my head. That seemed to satisfy her. I tied my hair back up with the lace-it was a nerve-wracking moment." Axis territory was a boiling pot of suspicion, so spies had to keep all their wits about them if they wanted to stay alive (per Atlas Obscura).

Spies used morse code while knitting

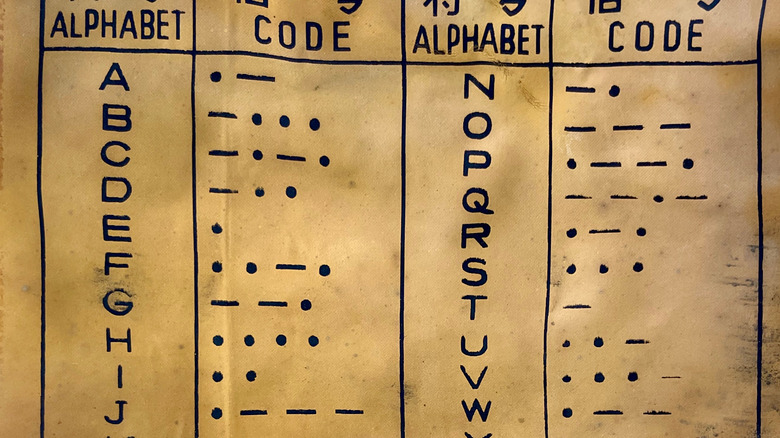

Sometimes, the scarf or sweater taking shape across the lap of a spy was entirely irrelevant to whatever imperative message that needed to reach the top. Morse Code — a system of denoting numbers and letters using pulses, noises, or lights in a certain sequence — was developed by Samuel F.B. Morse during the 1830s. According to Britannica, Morse's method was later taken on by government entities for correspondence purposes and became the prime form of communication for the telegraph.

For wartime purposes, the inconspicuous nature of Morse Code proved useful to spies. Madame Levengle, who masqueraded as a schoolteacher during World War II, would reportedly sit knitting in an upstairs room of her house while tapping her foot against the floorboards. Children pretending to do schoolwork on the house's lower level would decipher the sequence of her stomping that translated to a message in Morse. They'd then write the words down on paper and prepare the secret message for delivery to Allied forces. Other spies throughout Europe employed the same ruse (via Lit Hub).

Germans also used the knitting system

The knitting method wasn't limited to spies within the Allied ranks. Germans also caught on to the practice and would, according to various accounts, knit entire sweaters that contained elaborate codes. Essentially, if a message was woven into a garment, it was likely to remain undiscovered if the piece of clothing was exceptionally large, thereby making it harder to find the code's location. In effect, Germans also knew to keep a watchful eye out for seemingly innocent old women who were hard at work with knitting needles (via Atlas Obscura).

"When the German authorities carefully unraveled such a sweater, the story went, they found the wool thread dotted with many knots," author L. J. Adlington shared in her book "Stitches in Time" (per Atlas Obscura). "By marking a vertical door frame with the letters of the alphabet, spaced an inch apart, the knots could be deciphered as words by measuring the yarn along this alphabet and marking which letters the knots touched."

Knitting codes predated WWI and WWII

While it wasn't necessarily a "transcription" process like the ones used by spies during both World Wars, yarn was by no means irrelevant to earlier methods of covert communication. Handwoven Magazine reports that during the Revolutionary War, Molly "Mom" Minker utilized yarn to send messages to colonial troops. Fed up with British occupation throughout her town and in her own home, Rinker would eavesdrop on conversation between members of The King's Army and transfer her secret knowledge to a small sheet of paper. She'd then wrap it around a rock, which she in turn wrapped in a garment she'd fashioned out of yarn, and hide it in the nearby woods for rebels to find.

Around the same time on the other side of the world, female bystanders at public executions would casually knit red caps and sell them to rebels. The head pieces became trademark for French soldiers in open resistance. While it was far from a system of secrecy and codes produced by spies, yarn was instrumental nonetheless, albeit in a more symbolic way (per Lit Hub).