The Time The US Government Prosecuted Over 100 Communist Party Leaders

After the Second World War, the United States government decided that in addition to fighting communism in the Cold War, they would wage a domestic battle as well. And for over 20 years, hundreds of American socialists were targeted and persecuted for their political beliefs.

Some American socialists were arrested and fined while others were deported from the country. Many of those who were targeted were members of the Communist Party of the United States, and ironically, they were some of the ones who applauded when the persecutions started.

Although the Communist Party of the United States continues to exist after over 100 years of existence, the beating it took in the 20th century left it all but unrecognizable. And this was neither the first time socialism was attacked in the United States nor was it the last. This is the story of the time the U.S. government prosecuted over 100 Communist Party leaders.

Socialism in the USA

The socialist movement in the United States grew during the 19th century as it became involved in the American labor movement. People like Lucy Parsons and Eugene Debs pushed for a recognition of workers' rights and an abolition of capitalism, but in response, they found themselves repeatedly targeted and harassed by the United States government. Similarly, incidents like the Haymarket Affair in 1886 reveal the lengths to which the United States government was willing to go to suppress leftist opposition.

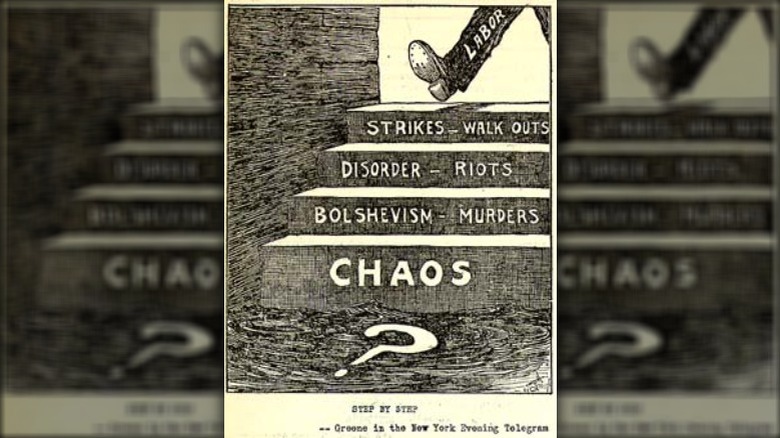

In "Political Economy of Labor Repression in the United States," Andrew Kolin writes that the suppression of strikes during the end of the 19th century were "all taken in the name of oppressing labor Communism." And after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, both the American government and American capital became convinced that the American labor movement was associated with the Russian revolution in one way or another.

In response, the American government manufactured what's known as the First Red Scare, which saw its peak in 1919-1920. By 1923, the FBI was tracking up to 450,000 people. In addition to waves of arrests and deportations, laws were also introduced that established penalties for speaking out against the United States. This was done under the cover of the First World War, but PBS writes that the war became an excuse to prosecute "labor activists, dissidents, and radicals — especially the anarchists, Wobblies [IWW members], and left-wing socialists."

What was the Smith Act?

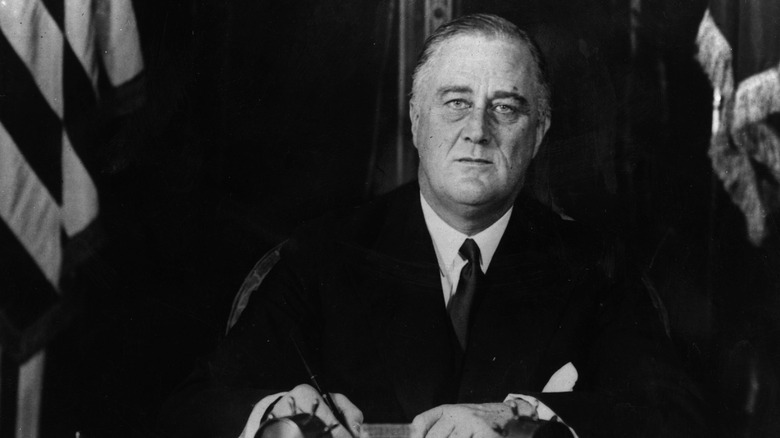

The Alien Registration Act of 1940, also known as the Smith Act, was signed into law by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on June 28, 1940. One of the provisions of the Smith Act mandated that all adults who were not citizens of the United States were required to register with the federal government and agree to be fingerprinted. The second provision made it a crime to "knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the duty, necessity, desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States" or even associate with any organization that may be accused of similar charges, writes the University of Washington.

According to "Trotskyists on Trial" by Donna T. Haverty-Stacke the passage of the Smith Act marked a huge shift in the legislation surrounding the protection of free speech in the United States. And Dickinson College refers to the act as "one of the most effective weapons in the government's arsenal during its domestic war on communism."

The Smith Act during WWII

In 1941, the United States government used the Smith Act for the first time against a group of Trotskyist Socialist Worker Party (SWP) members. Twenty-eight people were charged under the Smith Act and, according to "Fear Itself" by Ira Katznelson, all 28 persons were either members of the SWP or Local 544 of the Teamsters Union in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The Militant writes that there was support amongst the labor movement to free the imprisoned SWP members, but the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) refused to speak out against the persecution. In fact, top CPUSA leaders even went so far as to assist the police by giving them documents to help in their prosecution of SWP members and union leaders.

The trial lasted from October to December 1941 and in the end, 18 people were convicted of violating the Smith Act. Meanwhile, Communist journalist Milton Howard wrote in the Daily Worker that "The American people can find no objection to the destruction of the Fifth Column in this country. On the contrary, they must insist on it." Little did he know that in just five years, the law would be turned against the CPUSA as well.

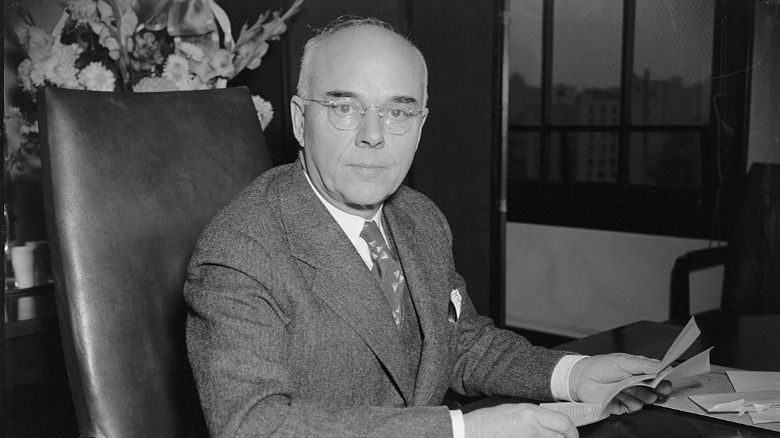

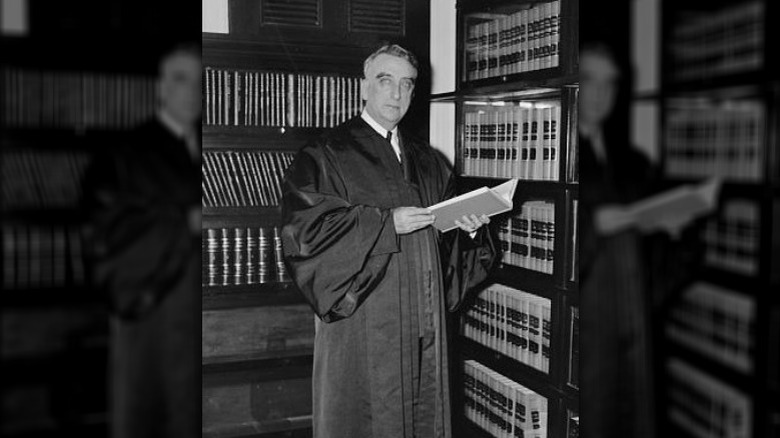

In 1944, the Smith Act was also used to prosecute up to 30 American fascists, but after Judge Edward Eicher (pictured) died of a heart attack during the trial, his replacement, Judge Bolitha Laws, declared a mistrial, according to "The National States Rights Party" by Michael Newton.

Hoover and the CPUSA

In 1945, the CPUSA was the strongest it had ever been with upwards of 80,000 members. And this didn't escape the attention of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. According to "Spying on America" by James Kirkpatrick Davis, Hoover and the FBI began investigating the CPUSA and in March 1946, Hoover informed Attorney General Tom C. Clark that their investigation into the Communist party nationwide was intensifying. In addition, they also started monitoring groups that weren't associated with the Communist Party but were considered to be promoting "party objectives," such as organized labor and civil rights groups.

In addition to the FBI's Security Index, which listed people who were to be detained by the FBI during a national emergency, a Communist Index was also created. This list included practically every single known member of the CPUSA in the entire country.

Hoover wasn't one to shy away from making his feelings about communists known. During a speech before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, Hoover referred to the "venom of the American communists" and claimed that communism was "an evil and malignant way of life. It reveals a condition akin to disease that spreads like an epidemic; and like an epidemic, a quarantine is necessary to keep it from infecting the nation."

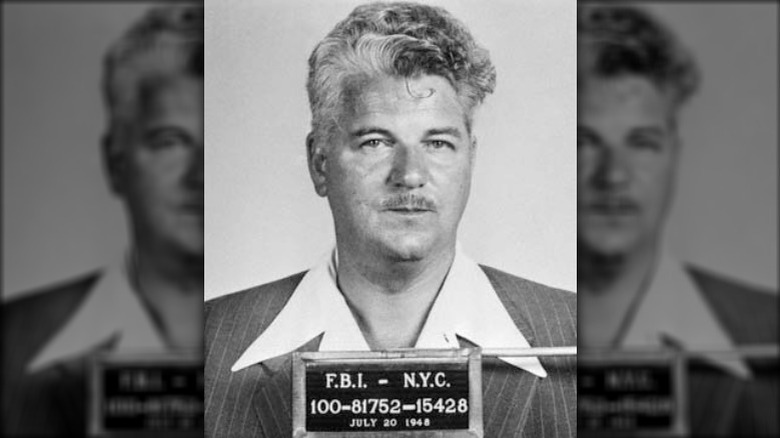

A dozen communists

On July 20, 1948, 12 members of the CPUSA's Central Committee, including party leaders such as Eugene Dennis (pictured), Henry Winston, Gil Green, and Robert Thompson, were indicted by a federal grand jury for violating the Smith Act by conspiring to subvert the United States government. However, the indictments alleged "no overt act whatever, except 'teaching and advocating the principles of Marxism-Leninism,'" according to the 1956 House Committee Hearings on Un-American Activities. As Dorothy Healey and Maurice Isserman note in "California Red," "it was not so much a trial of the defendants as of one of the books they had read."

The trial, which became known as the "Battle of Foley Square," lasted from January to October 1949 against 11 defendants, since the trial against Nation Chairman William Z. Foster was separated due to his failing health, reports LIFE Magazine. During the trials, the prosecution sought to prove that even if the defendants hadn't explicitly planned a revolution, they were guilty by association with the CPUSA. Black Perspectives writes that many of the witnesses used by the prosecution were paid former CPUSA members who were paid to testify that the Party advocated for a revolution. One of the witnesses, Harvey Matusow, would later admit that he and others had lied during the trial.

The CPUSA described the arrests as a frame-up, an attack on the Bill of Rights, and a "fascist provocation," according to the Report of the Subversive Activities Control Board.

11 guilty verdicts

After a 10-month trial, the jury found all 11 defendants guilty of violating the Smith Act on October 14, 1949. According to the Center Daily Times, 10 defendants were sentenced to five years imprisonment as well as a fine of $10,000. Robert G. Thompson, the 11th defendant, was instead given only three years due to his wartime service. And LIFE Magazine reports that those weren't the only sentences given out that day. After the guilty verdicts were given, all of the lawyers of the CPUSA members were given "sentences varying from 30 days to six months in jail for contempt of court."

At the time, this trial was the longest federal criminal trial in American history, surpassing the 1944 sedition trial. It was also "the most picketed trial in U.S. history" of its day. It was reported that at times, there were several thousands of picketers outside of the trial. The House of Representatives even went on to pass a bill outlawing picketing at federal trials during the trial, but the Senate never ended up voting on it. The trial also reportedly cost the American government over $1 million in legal fees, equivalent to over $11 million in 2022.

But despite the picketers, there was little public support for the defendants in the 1949 Smith Act trial. According to "California Red," unlike the 1920-21 trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, "there was almost no public outcry."

Supreme Court affirms

After the trial, the 11 members of the CPUSA appealed their conviction. But after taking their case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, their convictions were sustained by Judge Learned Hand, according to "Freedom of Expression in the Supreme Court," edited by Terry Eastland.

In response, the case was taken all the way to the United States Supreme Court. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court, in an opinion authored by Chief Justice Fred Vinson (pictured), ended up similarly affirming the decision against the CPUSA members in Dennis v. United States in 1951, effectively affirming the Smith Act's constitutionality. And the United States government heard the Supreme Court ruling loud and clear. In less than a decade, the Justice Department made up to 150 indictments under the Smith Act.

According to "The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America" by David Schultz and John R. Vile, this Supreme Court decision in Dennis v. United States was the "most restrictive decision the Court would issue concerning free speech."

Second-tier trials

The Supreme Court decision led the FBI to renew their persecution of communists with full force. Just two weeks after the Dennis v. United States decision, the FBI arrested 17 more leaders of the CPUSA. This time, they went after the second-tier leaders (including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, pictured). And according to "Trotskyists on Trial," over the following three months, an additional 24 CPUSA members were also arrested. By the end of 1951, the Justice Department had indicted 68 members of the CPUSA under the Smith Act.

ABA Journal writes that many of those who were accused under the Smith Act also struggled to find lawyers who could represent them. Having seen what happened during the 1949 Smith Trials, few lawyers were eager for that kind of adverse publicity and financial sacrifice.

The waves of prosecutions continued over the years and were especially strong in 1954 and 1956. The fear that communists were going to take over Hawai'i was also the alleged reason behind the arrest and trial of the Hawaii Seven in 1951, according to "Shaping History" by Helen Geracimos Chapin.

Hundreds of arrests

In total, almost 150 people were indicted under the Smith Act throughout the 1950s, running in tandem with the era of McCarthyism. Out of those indicted, over 100 went to trial and 93 were convicted. And while some of those who were convicted were given relatively short prison sentences, Black communists like Benjamin J. Davis Jr., Pettis Perry, and Claudia Jones all received prison sentences of up to three years and were fined up to $6,000. According to "W.E.B. Du Bois" by Charisse Burden-Stelly and Gerald Horne, Jones was also deported in 1955. Others, like Roberto Galvan, were deported after marching to stop police harassment in California, writes the NYLS Law Review.

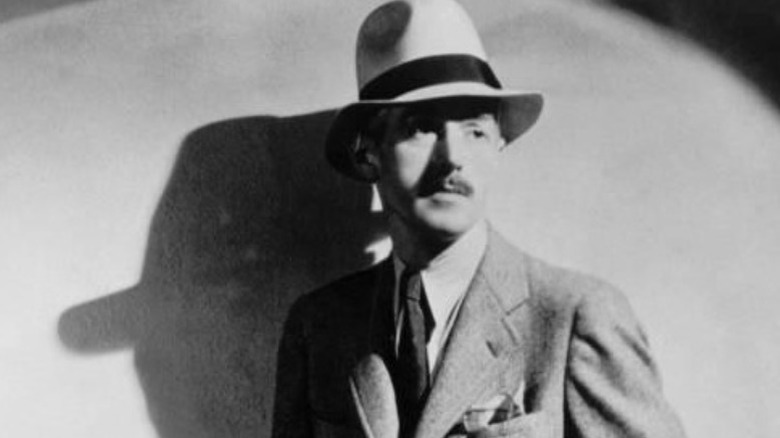

The Bail Fund for the CPUSA was also targeted. One of the trustees of the bail fund, author and activist Dashiell Hammett (pictured), was called before a grand jury and sentenced to six months in prison when he invoked the Fifth Amendment after being asked to name the contributors to the Bail Fund. And after he was released, he was blacklisted from radio, television, and films, and was audited by the IRS.

Many people in various occupations were also made to sign pledges stating that they weren't affiliated with the CPUSA. Even the American Bar Association, according to "In Calmer Times" by Arthur J. Sabin, briefly required such pledges and between 1951 and 1953, recommended that attorneys who advocated for Marxism-Leninism be "expelled from the practice of law by state regulatory bodies."

Red Monday

The anticommunist persecution by the American government continued until a series of Supreme Court rulings in 1957 challenged and restricted their power. According to the "Historical Dictionary of the 1950s" by James Stuart Olson, the final Supreme Court decision in regards to the Smith Act was Yates v. United States, in which the Supreme Court ruled that discussing the merits of overthrowing the government is not the same as actively planning to do so. In doing so, the Supreme Court reversed the convictions of 14 CPUSA members.

The Supreme Court released the rulings for four cases, including Yates v. United States, on June 17, 1957. This day became known as Red Monday and although many applauded the ruling for "restoring the credibility of the Bill of Rights," FBI Director Hoover condemned the decision and claimed that the Supreme Court was promoting communism.

However, according to "Historic U.S. Court Cases" by John W. Johnson, despite the seeming win from the Supreme Court, the ruling in Yates v. United States was "carefully avoided a direct reversal of Dennis and forced on two largely semantic issues."

One final conviction

The last prosecution under the Smith Act occurred in 1916 with Scales v. United States. According to "The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America" by David Schultz and John R. Vile, while all the other prosecutions under the Smith Act were based on a charge of organizing, Scales v. United States is the only Supreme Court case where the individual was convicted under the membership clause of the Smith Act, effectively prosecuting him for just being a member of the CPUSA. And unlike some of the other indictments, Scales wasn't charged with being involved in violent or subversive activities.

Scales was part of the Community Party in North Carolina and was involved in the coordination of civil rights and labor organizing activities in the Southern United States. The New York Times reports that Junius Scales was first arrested in 1954 and despite the case making its way to the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court ended up upholding his conviction and he was sentenced to six years in prison. It's also notable that Scales' conviction was upheld four years after the Yates decision, making him the only person convicted after the Yates decision. According to "The Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties," this was reportedly because of the martial arts demonstrations given by Scales.

Scales served 15 months of his sentence before President John F. Kennedy commuted his sentence on December 24, 1962.

What happened to the CPUSA?

By the 1960s, the persecution under McCarthyism and the Smith Act had taken a toll on the CPUSA. According to "Americans and the Wars of the Twentieth Century" by Jenel Virden, by 1956 membership numbers were dwindling to less than 5,000 and many historians state that most of the remaining members, if not one in three, were FBI agents or informants.

The waning influence of the Smith Act also coincided with the rise of COINTELPRO, so the FBI was easily able to continue harassing and keeping tabs on CPUSA members. According to the Senate Hearings before the Committee on the Judiciary, the FBI boasted that "the success of the FBI in this regard has been so outstanding that the Communist Party in this country doesn't know which of its Communist members to trust."

According to SNAC, the CPUSA was also affected when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev acknowledged some of the genocides committed under former Premier Joseph Stalin in 1956. Although many in the CPUSA had denied the reports of Stalin's genocides, after Khrushchev's acknowledgment, many had to face reality. The suppression of the Hungarian Revolution was also a blow to many CPUSA members. Paul Buhle and Dan Georgakas write in "The Encyclopedia of the American Left" that although some sought to acknowledge the crimes of the Soviet Union, by this point the majority of those who remained in the CPUSA were either Stalinist loyalists or FBI agents. The organization wouldn't recover until the 1970s.