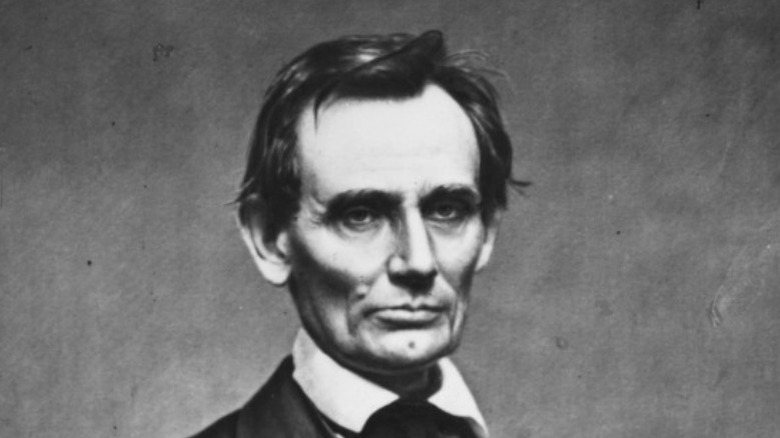

The Truth Behind Abraham Lincoln's Relationship With Frederick Douglass

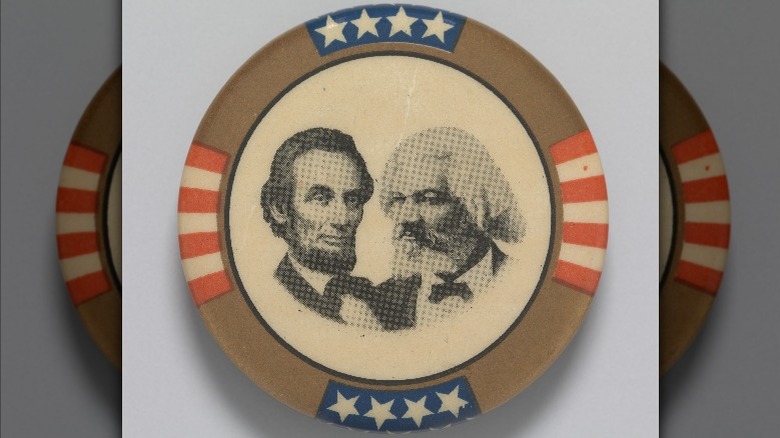

In the mid-19th century, the United States spiraled down a path towards Civil War and bloodshed. The election of an antislavery candidate to the presidency signaled to many that a showdown was going to come between rivals in the north and south. Yet, at the same time, two remarkable men who were polar opposites in almost every way, shape, and form came together to work for the future of America. President Abraham Lincoln and former enslaved person Frederick Douglass developed a friendship during the Civil War that was based on mutual respect and appreciation. According to History, Douglass was one of the most influential African-American speakers in the world at the time. He was an excellent orator whose stories of bondage and enslavement deeply resonated with many sympathetic members of the public.

Unfortunately, Lincoln and Douglass' relationship was not destined to be long, as John Wilkes Booth killed the president during a performance at Ford's Theater in 1865. In the annals of history, their friendship has been mythologized and, at times, hyperbolized, but the two men undoubtedly shared a close bond over their several meetings. This is the truth behind Abraham Lincoln's relationship with Frederick Douglass.

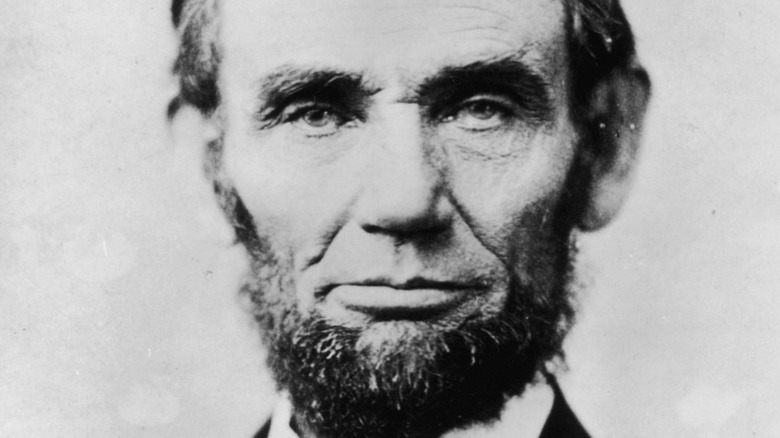

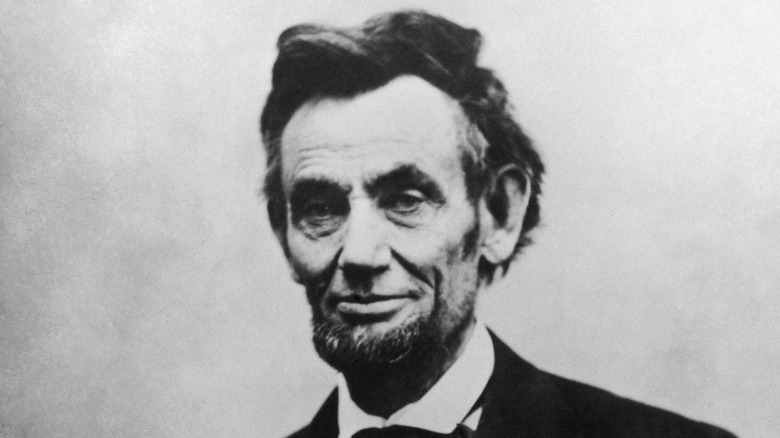

Abraham Lincoln and slavery before the Civil War

Abraham Lincoln's life was surrounded by slavery from the very beginning. According to David Herbert Donald in "Lincoln," when he was just a young boy, Lincoln's father moved the family from Kentucky to Indiana because of his opposition to slavery on both moral and religious grounds. Lincoln grew up in Indiana, living in a small log cabin while his family struggled with poverty. During his law career, Lincoln argued several cases involving slavery. Sometimes Lincoln defended the enslaved, and other times he defended the enslavers (per "Lincoln"). However, his willingness to take cases involving enslaved people or enslavers was not a referendum of his thoughts on the institution of slavery — he simply could not afford to turn away any prospective clients, regardless of their problems.

In 1858, Lincoln made his famous "House Divided" speech after accepting the Republican nomination for the presidency. The speech contained Lincoln's famous proclamation, "A house divided against itself cannot stand ... I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free ... It will become all one thing, or all the other." In the 1860 election, Lincoln received 1,866,452 votes — just under 40% of the popular vote, but enough to win the presidency. This caused the southern states to start seceding from the Union, which brought on the Civil War.

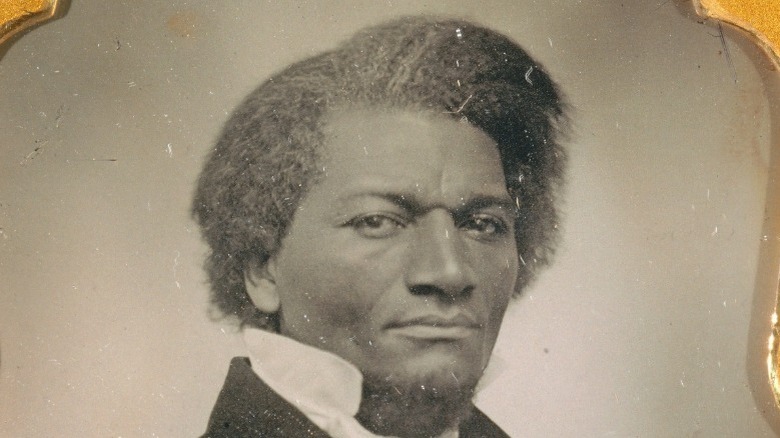

Frederick Douglass and his escape from slavery

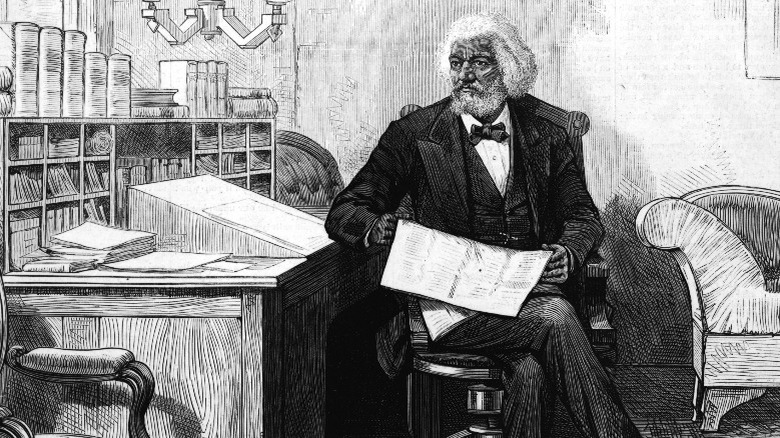

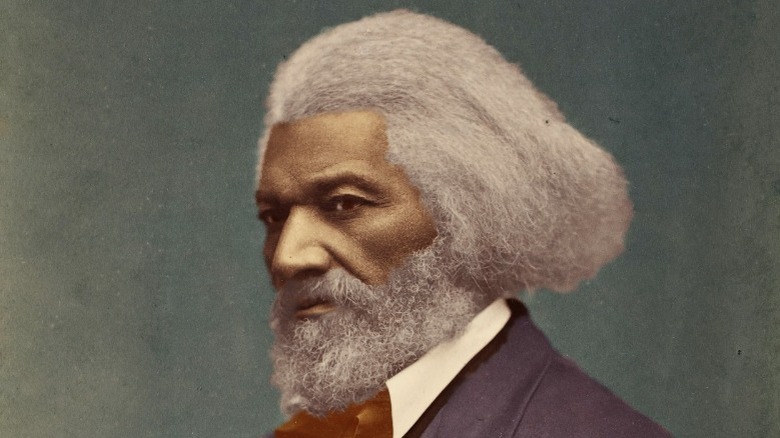

Before Frederick Douglass was a famous and renowned orator and public speaker, he endured a tragic life of slavery. According to his autobiography, "The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," he was born in Talbot County, Maryland. He didn't know the date or year of his birth, which was not uncommon for enslaved people in his area, and he guessed he was born in 1817. Enslavers destroyed his sense of community and family, and when they forcibly took him from his grandmother as a child, it was a traumatizing experience.

Douglass escaped from slavery when he was aged 20, and he adopted the surname Douglass to replace the name given to him by his enslavers (via the University of North Carolina). He wrote three autobiographies during his life, and he immediately started working as an abolitionist after his escape. According to the university, Douglass saw the Civil War as a "moral crusade to eradicate the evil of slavery." He traveled throughout the country and gave speeches on issues relating to racism, and he eventually became a respected editor and minister to Haiti in 1889. Douglass died in 1895 and is still respected as one of the most charismatic and influential speakers in American history.

Douglass supported Lincoln for President in 1860 before they had even met

Leading up to the 1860 election, Frederick Douglass was conflicted about who to support. David W. Blight argues in "Frederick Douglass" that the activist saw Republicans not as true opponents to slavery but rather as just opposed to the power that enslavers could wield politically. Still, he saw supporting the Republicans as his only real option because they at least "humbled the slave power" and fought against it as an institution. Douglass expressed a willingness to work with the Republicans even though he was disappointed by their overall platform. He wrote an article a few months before the election that was positive toward Lincoln.

In the months leading up to the election, Douglass continued to stump for Abraham Lincoln by giving many speeches, and he was involved in other campaigns, like trying to abolish the racist $250 property requirement for Black voters in New York (per Blight). He also worked as a recruiter, getting Black soldiers to join the war effort. A month after the election, Douglass wrote an article in his newspaper, "Douglass' Monthly," in which he stated the nomination of Lincoln "demonstrated the possibility of electing ... an anti-slavery reputation to the Presidency of the United States."

Douglass was initially at odds with Lincoln over his policies

Even though Frederick Douglass supported the Republicans, he still lamented what he saw as the shortcomings of the new Lincoln Administration. These included refusing to entirely abolish slavery throughout the country and not repealing the contentious Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (via the University of Rochester). Among other policies that angered Douglass was Abraham Lincoln's proposed plan to send African Americans to Liberia or Central America to start a free Black colony (per The White House Historical Association). At the time, Lincoln wrongly believed that free Black and white Americans would never be able to live in harmony in America, even after emancipation and the end of slavery. His push for a new Black colony in Africa offended Douglass as a racist and stupid proposition.

In 1862, Lincoln famously held a meeting with influential Black leaders at the White House, where he talked about the colonization plan, and he declined to invite Douglass. A few months later, Douglass publicly called out Lincoln in a scathing article in Douglass' Monthly. In the article, Douglass criticized Lincoln's handling of the Civil War and castigated him for being "quite a genuine representative of American prejudice and Negro hatred." He claimed Lincoln was missing a "genuine spark of humanity" and did not really care about improving the lives of previously enslaved Americans.

Their first conversation was about Black troops fighting the Civil War

Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass did not meet each other until August 1863, nearly two-and-a-half years into the Civil War. Douglass was upset at the treatment of Black troops fighting in the 54th Massachusetts regiment, especially their tragic fates after being captured by Confederate soldiers (per David W. Blight in "Frederick Douglass"). Douglass traveled to Washington to meet the president on August 9, and it must have been an emotional journey for Douglass as he entered into Maryland for the first time since he had escaped slavery nearly 25 years earlier.

Douglass showed up at the White House uninvited, but he used his connections to gain access to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and, eventually, Lincoln. During his meeting with Stanton, the secretary suggested that Douglass travel toward the front lines of the war near the Mississippi River valley to help recruit more Black troops, which Douglass agreed to do. When Douglass had his meeting with Lincoln, his opinion of him completely changed. Lincoln awed Douglass with his presence and demeanor, and Douglass came away from the meeting with newfound respect for the president. They talked about the conditions of Black soldiers fighting the war, and Douglass thanked Lincoln for pushing for equal pay for them.

Lincoln wanted Douglass to help him free slaves stuck behind Confederate lines

A year later, in August 1864, Abraham Lincoln invited Frederick Douglass back to the White House for another meeting (per the National Parks Service). Lincoln wanted to enlist Douglass' help in a scheme that involved going behind enemy lines into the confederacy and helping slaves escape from bondage. According to Russell Freedman in "Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass: The Story Behind an American Friendship," Lincoln wanted Douglass to establish a group of Black men who would travel as government agents and spread the word of the Emancipation Proclamation. During their meeting, Lincoln kept the governor of Connecticut waiting for over an hour so he could finish talking with Douglass. This shocked Douglass — that Lincoln would make a white man wait in the hall while they talked — and went a long way toward convincing him of Lincoln's sincerity.

In his autobiography, Douglass wrote about his meeting with Lincoln. He said that Lincoln had expressed regret over the lack of enslaved people that had come north due to the Emancipation Proclamation, and Douglass suggested the enslavers had likely hidden the truth about it from the enslaved. When Lincoln won reelection in 1864, the scheme was abandoned, but it showed the depth of Lincoln's respect for Douglass as an influential Black American.

Douglass felt Lincoln treated him like an equal

While he may have been skeptical of Abraham Lincoln prior to their meetings, by the end of their second encounter in August 1864, Frederick Douglass thoroughly respected the president. According to his autobiography, Douglass claimed Lincoln "showed a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I had ever seen before." He repeatedly called Lincoln a "great man" and said that he never felt discriminated against during any of their conversations. This was in stark contrast to his feeling about Lincoln just over a year earlier, and it showed how much their friendship had grown through their meetings.

A few days after their second meeting, Lincoln invited Douglass over to the White House for tea. Lincoln even sent over a horse and carriage to pick up Douglass and bring him back to the Soldiers' Home where he was staying. Douglass had to decline because he was scheduled to give a speech at the same time and said not meeting Lincoln was one of his biggest regrets. He felt that Lincoln truly respected him as a person and a Black organizer, and he wrote about supporting Lincoln for the 1864 election over his rival, former Union Gen. George B. McClellan.

Douglass attended Lincoln's 1865 inauguration

After Abraham Lincoln won reelection following a contentious election season, Frederick Douglass attended his inauguration in March of the following year (per his autobiography). He met with Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Salmon Chase (pictured above) the night before and even helped him try on the new robes that he was going to wear during the ceremony. Douglass expressed anxiety during Lincoln's inauguration and subsequent parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. He was worried that Confederate saboteurs could be stationed along the route, waiting to assassinate the unsuspecting president. Thankfully, those fears were unfounded, and the president made it back to the Capitol building, where he was officially inaugurated and gave a speech.

Douglass was moved by the address, which he described in his autobiography as "contain[ing] more vital substance than I have ever seen in a space so narrow." He claimed that he repeated the speech to friends and colleagues several times in the years afterward because it was so powerful. However, Douglass came away with a very unfavorable opinion of Lincoln's vice president, Andrew Johnson. He called him a "demagogue" who "certainly is no friend of our race."

Their final meeting followed the inauguration

According to Russell Freedman in "Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass," after the inauguration, Frederick Douglass sought out another meeting with Lincoln, this time in the White House. However, as Douglass approached the White House door, two police officers stopped him from entering. They told him they had been given explicit instructions not to allow any Black people into the building. In his autobiography, Douglass wrote that they tried to usher him away, but he exclaimed, "I shall not go out of this building till [sic] I see President Lincoln." He found someone he recognized and gave them a note to give to the president, alerting him to their presence.

Lincoln quickly came out to see Douglass. Douglass described Lincoln as a towering figure and claimed that the president recognized him even before he could reintroduce himself. Their interaction was very brief, but Lincoln told Douglass, "There is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours." Douglass felt honored to have spoken with Lincoln again, and though he did not realize it at the time, this would be the last time they would ever meet.

Douglass praised Lincoln after his assassination

Just under a month after Abraham Lincoln's inauguration and his final meeting with Frederick Douglass, the Union officially defeated the Confederacy in the Civil War after the battle of Appomattox. Just a few days later, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln while was watching a play at Ford's Theater in Washington (via "Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass"). Douglass was in Rochester, New York, when he heard about Lincoln's death, and when he found out, he was devastated. In his autobiography, Douglass wrote he was "stunned and overwhelmed" by the news and so shocked he could hardly speak at first.

Later that night, he gave a speech at the city hall in Rochester that was incredibly emotional and filled the audience with sympathy. Douglass lamented that Lincoln was not going to be able to preside over his second term, where he could actually govern the country how he wanted, instead of conducting a war. He called the country "redeemed and regenerated" from the Union victory in the war and originally had very high hopes for what Lincoln's second term was going to bring.

Mary Todd sent Lincoln's cane to Douglass as a token of their friendship

After Abraham Lincoln's assassination, the country collectively grieved for his death (at least in the Union). According to Russell Freedman in "Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass," Frederick Douglass took Lincoln's death hard and viewed it as not just a personal loss but also a loss for the nation. A few months after his death, Douglass received a strange package in the mail. It was long and slender and was from Lincoln's widow, Mary Todd.

In the package was the former president's "favorite walking stick" and a note from his widow. The note said that Lincoln had considered Douglass a "special friend" and that even before he died, he had wanted to send Douglass something as a sign of respect and friendship. Since he died too soon, Mary Todd decided to make good on her husband's plan, so she sent Douglass the staff. Douglass was still grieving when he received Todd's present, and he was grateful to have a reminder of Lincoln after his death.

On the 11th anniversary of Lincoln's death, Douglass gave a final speech praising his former friend

After Abraham Lincoln's death, Frederick Douglass continued to mention him during his speeches and orations. He frequently talked about Lincoln's accomplishments in the Civil War and getting rid of slavery, which he called Lincoln's "greatest mission" (via "Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass"). Eleven years after Lincoln's death, Douglass gave a speech about him at the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C. The monument itself depicts Lincoln extending his hand to a kneeling ex-enslaved person and is known colloquially as the Freedmen's Monument (via the Smithsonian).

In his speech, Douglass continually praised Lincoln for his contributions to freeing the slaves. He praised Lincoln's "exalted character" and called him "the first martyr President of the United States." He did mention that Lincoln was not always committed to antislavery and emancipation during his presidency but overwhelmingly praised him for eventually becoming a huge proponent of freeing the slaves and called him "a great and good man."

Douglass himself died in 1895, leaving behind an incredible legacy of courage and abolitionism. His last house is a national historic site in Washington D.C., and it is full of activities that explain his life and impact. Lincoln and Douglass are two of the most influential people in history, and their friendship serves as an incredible reminder of the ways Americans from all walks of life can come together.