The Last Cavalry Charge In History Was Later Than You Think

It may offend our modern sensibility, conditioned by televised war, but the cavalry charge was once considered the most dramatic, the most glorious of military tactics. Soldiers mounted on horseback would draw their swords and bring their mounts to a gallop, crashing into the enemy. (Those are Marshal Ney's curaissiers in the print above, at Waterloo.) Tennyson's "Charge of the Light Brigade" was only the most famous of many 19th century poems that celebrated these daring, sometimes suicidal attacks. "When can their glory fade? / O the wild charge they made!" — words memorized by schoolchildren for over 100 years (via Poetry Foundation).

It's easy to see how the cavalry charge came by its glamour. Horses are beautiful, and danger is attractive. Napoleon's general of light cavalry, the hard-drinking Lasalle, said that any hussar over the age of 30 was a bum (a "jean-foutre"); he himself died in battle at 34 (via Fondation Napoléon). Cavalry had panache. They wore extravagant uniforms and facial hair, like rock stars. Maneuvers like the charge, however rare and dangerous, moved people in ways that seem impossible today.

It seems a long time ago that anyone thought like that, and even longer that horses ever changed the course of a war. The machine guns, barbed wire, trenches, and gas of World War I made warhorses impractical. But cavalry did not go extinct. It hung on for longer than most people think — charges and all.

1917: Beersheva

The trench warfare of World War I forced many cavalry units to dismount permanently, as War History explains. But on some fronts, mounted warfare continued. Mikhal Sholokhov's epic novel "And Quiet Flows the Don," which won him the Nobel Prize, tells of cavalry battles on the Eastern front, between the Russian and Austrian armies wielding lances and sabers.

Cavalry played a particularly important role in the Middle East, where the British and French clashed with the Ottoman Turks. Most of the British cavalry was really mounted infantry, or dragoons: Infantrymen who rode horses or camels to reach the battlefield, but dismounted to fight (per New Zealand History). But occasionally, they fought as true cavalry, and this meant charges. In October 1917, the British Army surrounded the strategic town of Beersheva, in Palestine. It was a slog: German air raids had worn down the besiegers, who could not reach the Turkish trenches.

Just before dark on October 31, Lieutenant General Harry Chauvel had an idea. He ordered the Australian 4th Light Horse Brigade to mount and advance on horseback. None of the men had swords, so they clutched their bayonets instead. At about three kilometers, Chauvel ordered a gallop. The Turks opened fire, but the Australians were too fast, leaping over the gunners and scattering the Turkish infantry. It was a mad plan, and it paid off: the British marched into Beersheva that night, behind their horsemen (via the Australian War Memorial, London).

1942: Izbushensky

Horses continued to play a role in the irregular conflicts that followed World War I, like the Spanish Civil War. Even when World War II broke out, horses played a major, if generally off-field, role. Rare Historical Photos, which hosts images of German Wehrmacht troopers learning to fire rifle from the saddle, notes that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union used about 6 million military horses altogether, mostly to pull heavy artillery.

When Hitler launched his suicidal 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, Italian dictator Mussolini began sending divisions of his own (badly overstretched) army to help, as King's College London explains. Among these units were the Cavalleria Savoia, or Savoy Cavalry. On August 23, 1942, this unit found itself the unlikely hero of one of the kinds of battles many people already considered extinct.

Per History, near the village of Izbushensky, the 600 Italian troopers found themselves face-to-face with 2,000 Soviets, the latter dug in with machine guns and mortars. The horsemen, armed with swords and hand grenades, attempted the impossible: a glorious, 19th century-style charge into the Russian flank. It worked. The Italian horsemen closed the gap faster than the Russians could turn their guns around, and scattered them. As a battle, Izbushensky made little impact. But it was a huge coup for fascist propaganda. A suitably melodramatic movie, "Carica Eroica" (or "Heroic Charge"), was released immediately.

1942: Morong

Far from Russia, in the Philippines, the American army would have a similar, unexpected success. An American colonial territory since the Spanish-American War, the Philippines became a key target for the Japanese Army, who seized Manila in 1942 (via Defense Media Network). Some of the most savage fighting in the war would take place on the island of Luzon, as well as the infamous Bataan Death March (per History).

In the leadup to that vicious battle on Luzaon, an American mounted patrol from the 26th Cavalry (Philippine Scouts) entered the village of Morong, near the Japanese lines. The village was deserted, but as the American troopers reached the central square, shots rang out. Japanese infantry were just beginning their own breach of Morong. The advance guard had arrived; a larger force was likely just behind.

If the patrol retreated, they would give up the village. If they stayed, the Japanese would quickly overwhelm them. Their commanding officer, 24-year-old Lieutenant Edwin Ramsey, made a quick decision. Trusting that reinforcements would follow the sound of the guns, he drew his revolver and order a charge — the first U.S. cavalry charge in half a century. Again, it worked. The horsemen moved faster than the Japanese could react, trampling and shooting the advance guard. The patrol held Morong, suffering only three casualties. From there the story gets grim, however: the 26th, facing starvation over the next few months, would slaughter and eat all of its horses.

1966: Angola

The cavalry charges of World War II had an air of anachronism. This was part of their success: No one behind a machine gun expected to be charged by a man on horseback, swinging a saber. The cavalry of later wars would be less anachronistic and more pragmatic, part of a reliance on combined arms that continues to shape military tactics.

This new approach to cavalry was pioneered in Africa. In the late 1960s, the empire of Portugal was crumbling. The colony of Angola was in revolt, fighting the Portuguese army in woodlands and high grass. According to John P. Cann's book "Portuguese Dragoons 1966-1974: The Return to Horseback," the high grass in particular posed a tactical problem. It was too tall to see over and too thick to drive through. Helicopters could spot enemy troops hidden in the grass, but they were expensive, and could not establish friendly relations with civilians on the ground like infantry could.

The solution was a return to horses. Portugal's African Dragoons sat high enough in the saddle to see over tall grass, and could cover rough terrain faster than foot patrols. Often they moved in coordination with a helicopter, which could provide cover fire (depicted in a Portuguese-language report on YouTube). Portugal withdrew from Angola in 1975, exhausted and in debt, but the African Dragoons had been a stroke of genius, as clever as it was unexpected.

2003: Darfur

Angola was not the end of cavalry in Africa. The 1990s saw tensions in the country of Sudan boil over into war. As Britannica explains, Sudan's pastoral, Arab majority and agricultural, black minorities clashed over control of the government and relations with Sudan's neighbors, Libya and Chad. The violence would become a civil war, pitting the Arab government in Khartoum against black communities in regions like Darfur. These wars have claimed over 2 million lives, according to PBS, and displaced some 4 million refugees.

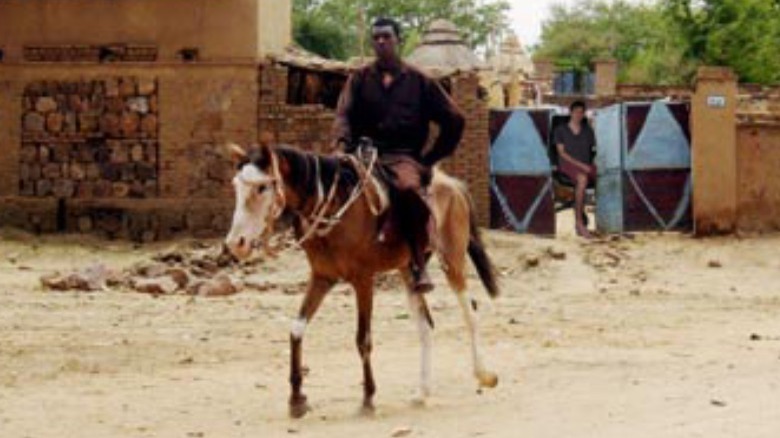

In 2003, the Sudanese government began enlisting the support of mounted Arab militias to kill and terrorize civilians in Darfur. These militias were known as "janjaweed," apparently derived from the Arabic words for jinn and horse. The janjaweed lived up to their sinister name, raping, murdering, driving off livestock, poisoning wells, and kidnapping children. Tactically, they specialized in combined arms operations, like the Portuguese dragoons in Angola. The initial attack would be by helicopter or bomber; then the horsemen would arrive, armed with military-grade weapons, courtesy of Khartoum.

Luckily, a UN peacekeeping operation in 2008 put a stop to the janjaweed's five-year pogrom. But neither the horses nor the horsemen are gone, and the Khartoum government, in a grim indication of its mood, has doggedly supported Russia's invasion of Ukraine (via Al Jazeera).

Afghanistan: 2011

When Barack Obama debated Mitt Romney ahead of the 2012 U.S. presidential election, he delivered a quip that made headlines. Romney complained that the U.S. Navy had fewer ships under Obama than it had in 1917. "Well, Governor," Obama shot back, "we also have fewer horses and bayonets" (via Reuters).

Fewer horses, surely, but even as Obama spoke, American serviceman were in the saddle on operations. Special Forces in Afghanistan found themselves in a similar situation as the Portuguese in Angola. The terrain was rough, impassable even to jeeps, but the war against the Taliban required mobility. The Afghans themselves rode sure-footed horses over the mountains, covering far greater distances than they could on foot. Low tech worked, and the Americans caught on immediately. A U.S. Army article notes that few of the Special Forces operators had any experience with horses at all, much less covering long treks through the badlands. Riding is as much an art as driving, and can take as long to perfect; it's also a physical activity, calling on muscles most people never use. But it worked.

As one Green Beret put it, "We're blending, basically, 19th-century tactics with 20th-century weapons and 21st-century technology in the form of GPS, satellite communications, [and] American air power." The armies evolve; the horse remains.