The Truth About US Presidential Frenemy, Roscoe Conkling

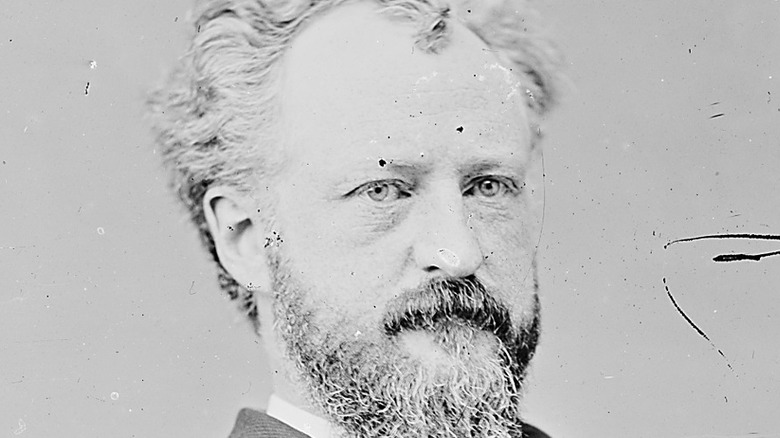

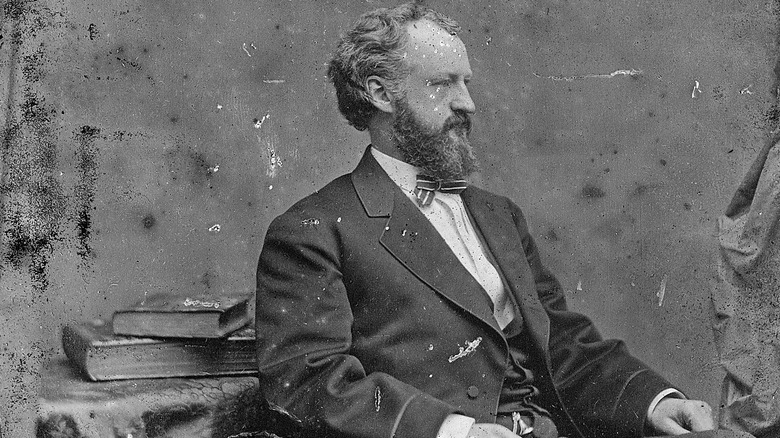

Roscoe Conkling: such a unique name alone is enough to pique one's interest. Yet, to the general public, it is a name in history that is mostly forgotten and overlooked today in history textbooks. In the years leading up to and following the Civil War though, Roscoe Conkling was a name well-known (and sometimes feared) to those versed in the current events and politics of the day. With his rise from a U.S. representative to New York to one of the most powerful Republican senators in Congress, Conkling's abrasive oratory and shrewd political maneuvers were as legendary as they were frustrating to his political opponents — who were often taken aback by his way of dress, which included bright colored shirts and pants during a time in which darks colors were dominant in the capital (per The Washington Post).

In many ways, Conkling was politically ahead of his time, proudly and assertively supporting issues that would have been considered controversial and progressive during his political career, particularly concerning race relations. As his power and influence increased on his quest to become to most powerful political force in New York, what he prioritized also changed. During the years following the Civil War, as Conkling's political power grew, it created a divide within the Republican Party itself as presidents and presidential hopefuls reckoned with a simple question: "Do I need to keep Roscoe Conkling on my side?"

He was influenced by his father to enter law

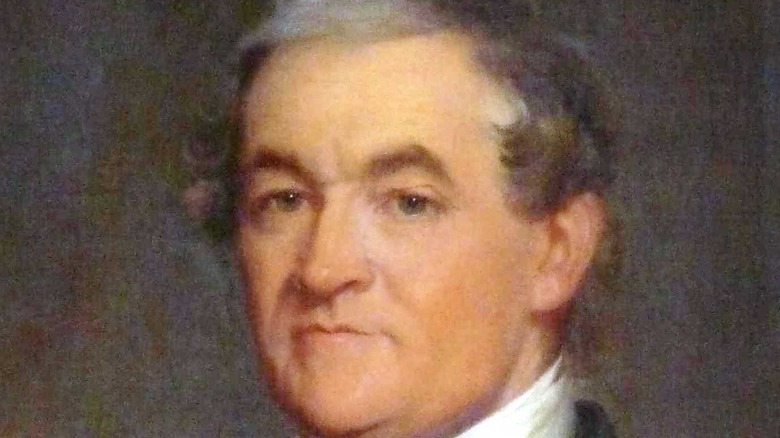

Roscoe Conkling was born in Albany, New York, on October 30, 1829, the son of Alfred Conkling, a former prosecuting attorney and U.S. representative who had become an influential U.S. district judge after being nominated to the position by President John Quincy Adams (per Federal Judicial Center and House.gov).

In 1939, the family then moved to Auburn at the suggestion of future secretary of state William Seward, where the young Conkling was initially only interested in riding horses and exploring the outdoors but was not so fond of reading or school, according to The Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling. When he was 13, his father then sent him to stay at the Mount Washington Collegiate Institute in New York City for a year, where he learned how to be a proper student and, as his later life would reveal, began to understand the power of oratory. As described in a biography by Henry Wilson Scott, after transferring to Auburn Academy, his peers recognized him as superior both inside and outside of the classroom.

At age 16, he began studying law, was admitted to the bar in 1850, and began practicing law in nearby Utica shortly after (per House.gov).

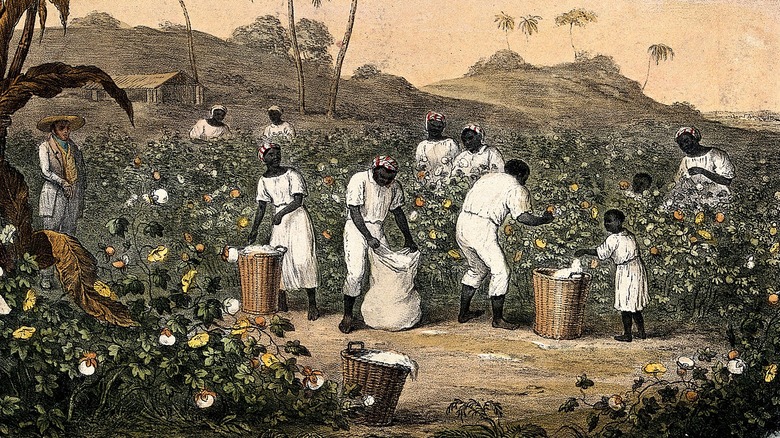

He was an early and staunch abolitionist

By the time he was 20 years old, Roscoe Conkling was a firm abolitionist when it came to slavery. This was an era in which the United States was a decade away from the Civil War, and many of those who were anti-slavery preferred the idea of gradualism, which was the belief that slavery should gradually be phased out rather than immediately dismantled (per Cornell). Conklin, who later as a politician would describe the system of slavery as a "barbaric and detestable crime" committed by the United States, knew that one way or another slavery would eventually be abolished throughout the nation (per NPS).

Later on in life, Conkling's long belief in abolitionism would come full circle. In 1875, a decade after the Civil War's end, Senator Blanche Kelso Bruce of Mississippi, who had been enslaved before the war, presided over the Senate and was ignored by many of the white senators in the room. As Senator Bruce walked down the aisle alone, due to being ignored by his fellow Mississippi senator, Conkling rose and joined him (per Senate.gov). As described by The Washington Post, Bruce never forgot this moment, and he and his wife named their first son after him as a result.

He was a 19th-century health nut

Read most biographical writings on Roscoe Conkling and this will inevitably be mentioned somewhere: the guy really took his health seriously. He also never drank nor smoked, like many of the men of his time (via WYNC). He was an imposing presence, regularly exercised, and was in great shape for most of his life. One contemporary referred to him in 1873 as "tall" and "well made" in addition to being "a very good looking man" that women of the era swooned over (via "Behind the Scenes in Washington").

He was known as a body-builder, enjoying boxing as a means for staying in shape, which led to him being so intimidating that while in Congress, he served as a bodyguard of sorts to U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens whose fiery anti-slavery speeches on the House floor in the late-1850s threatened to turn violent against him (per Lewis & Clark Digital Collections).

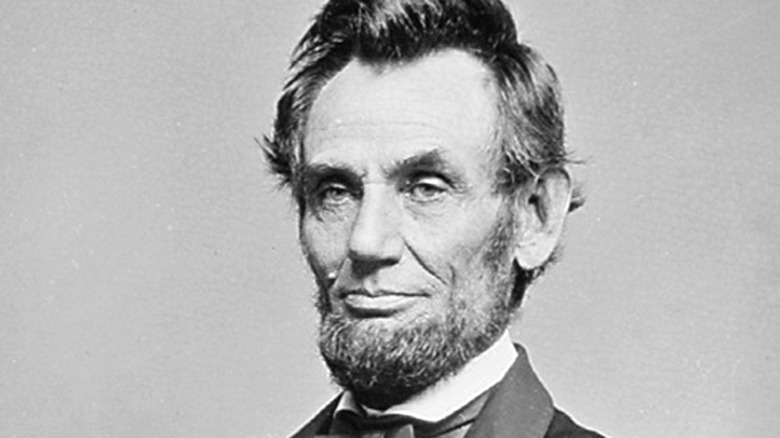

He supported Lincoln's presidency and the Civil War

After eight years as a district attorney, Roscoe Conkling toyed around with the idea of running for office and, in 1858, he became the mayor of Utica, New York, and then he ran on the Republican ticket for the U.S. House of Representatives, joining the 36th Congress in 1859 (per House.gov). Leading into the Republican Convention of 1860, he had supported family-friend and fellow New Yorker William Seward (the expected nominee), but Abraham Lincoln, coming off a Senate campaign defeat in 1858, won it in a surprise upset (per Britannica). Conkling immediately threw his support behind Lincoln for the general election. As described in "The Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling, he used his substantial oratory skills (and trademark humor) to help convince people of Lincoln's honesty and skill as a lawyer, while pushing back against the notion that he lacked manners due to being from Illinois.

As civil war broke out, he maintained his support for Lincoln as well as the war itself (via NPS). In March 1863, he gave a speech in support of the war, transcribed by The New York Times, in which he compared the Civil War to the Revolutionary War of their ancestors, declaring that they planted a tree of "religious, political and civil liberty" and they "watered it with their blood." In his re-election campaign the following year, Conkling received a personal endorsement letter from President Lincoln, whom he often embellished as a close friend of his (per NPS).

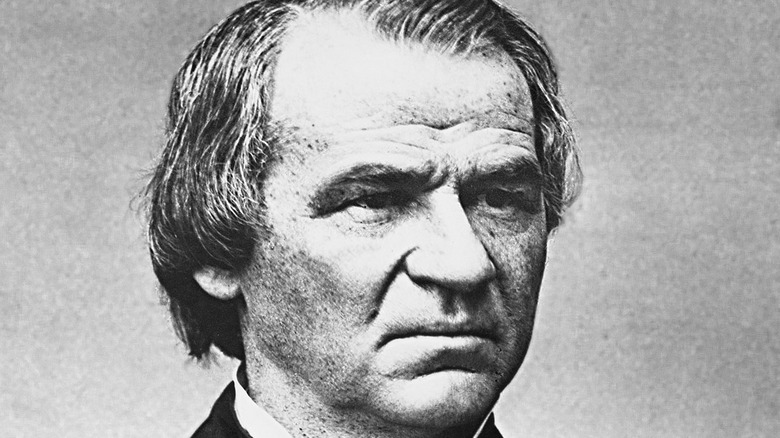

He became President Johnson's worst enemy during Reconstruction

After President Lincoln's assassination following the end of the Civil War, Vice President Andrew Johnson was sworn into office. For those who supported Lincoln's vision of post-war unification, they were gravely disappointed by President Johnson's leniency during the years of Reconstruction (per Britannica). It should be no surprise then that he became the sworn enemy of U.S. Representative Roscoe Conkling. Along with Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Conkling became a leader among a coalition of lawmakers known as the Radical Republicans, who believed in strict military occupation of the defeated Confederate states and advocated for more rights for freed slaves (per Britannica). As a result, Conkling and the Radical Republicans were one of the largest thorns in Johnson's side during his presidency. He publicly and viciously criticized Johnson as president, stating he "incited and emboldened" the "lawlessness, disloyalty and contempt" among former rebels in the south, going as far as saying he had made treason "more fashionable" than support of the union (via "Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling").

Eventually, the Radical Republican coalition would spearhead the impeachment of President Johnson in 1868, which became a full-blown constitutional crisis, according to Senate.gov. Conviction was a mere one vote short. And still, later in life, Conkling would compare Johnson to Napoleon III and call him an "angry man" who was "frenzied with power and ambition" (via "Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling").

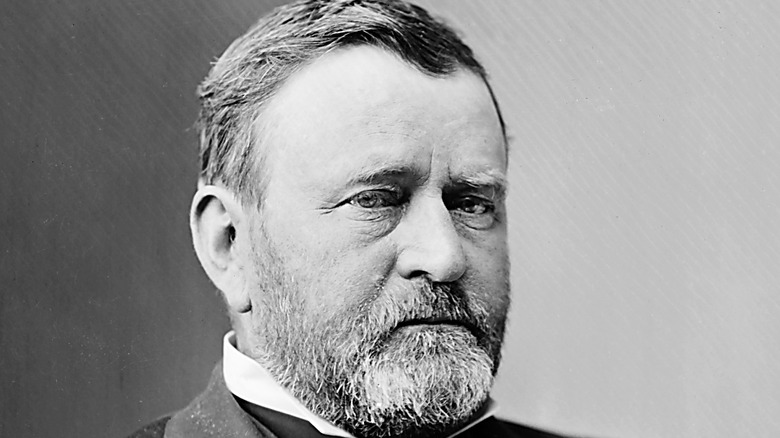

He was a powerful ally to President Ulysses S. Grant

After the disaster that was President Andrew Johnson, Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant easily won the presidential election of 1868 on the Republican ticket. Roscoe Conkling feverishly supported him — despite the fact that Grant was running against former governor of New York Horatio Seymour, Conkling's own brother-in-law (per NPS). Very early on during Grant's presidency, Conkling, who was by this point the de facto leader of New York's Republican Party, made himself influential on the Grant administration (per Britannica). Yet, as described in The American Journal of American History, despite being so publicly outspoken and so trusted by President Grant, the more that Conkling's power grew as he worked to increase the power of the Republican political machine, the less he was paying attention to the important issues of the day, leading to him having very little influence on meaningful long-term legislation in Congress.

As the Grant administration was increasingly plagued by scandal, there were calls for civil service reform to help prevent corruption and ineptitude in government, reforms which Conkling pushed back against, leading to a fracture within the Republican Party (via NPS). Although Conkling broke with Grant on his support of forming a commission to investigate potential civil service reforms, he still did not waver in his support of the president, whom he would even help campaign for a third term (per Lewis & Clark Digital Collection).

He believed in machine politics and opposed reform

Part of what divided the Republican Party entering the Gilded Age was the patronage system, a system passionately supported by Roscoe Conkling but one opponents accused of fueling machine politics and encouraging cronyism and corruption. Under this system, often called the "spoils system," elected officials could appoint anyone to federal positions without any oversight, leading to politicians appointing family members, friends, and supporters regardless of qualifications or proficiency (via NPS). For many of these appointments, appointees neglected their duties to instead use their positions as political operatives and organizers, describes The Miller Center.

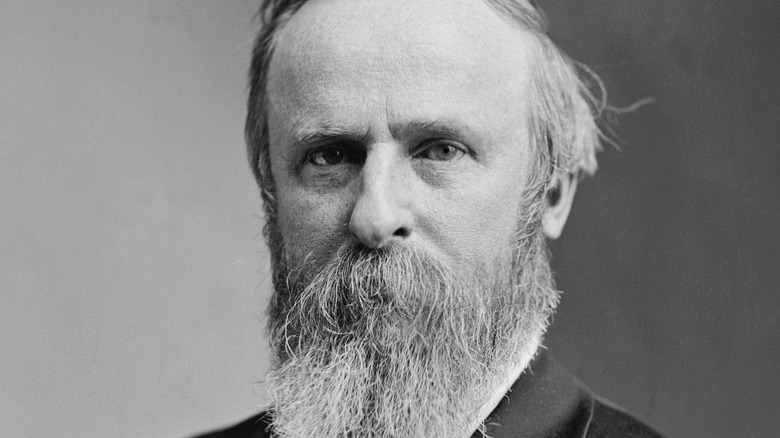

When Rutherford B. Hayes was elected president on the Republican ticket and vowed to support legislation reforming civil service requirements, Conkling used all of his influence and power to resist such changes (per Britannica). After all, it was the patronage system and the loyalty among appointees that made Conkling as powerful as he was in New York.

This divide within the party led to the solidification of growing factions called the Stalwarts and Half Breeds. The more conservative Stalwarts, led by Conkling along with his political machine ally Chester A. Arthur, made it their mission to stop Hayes's reforms, whereas the moderate, but slightly more liberal Half Breeds pushed strongly to end the patronage system, according to Britannica. And just to top it off, one of the leaders of the Half Breeds was James G. Blaine, a personal enemy of Conkling's dating back to their time serving in the U.S. House of Representatives together during the Civil War (via NPS).

He was a thorn in President Hayes' side

As described by History, the Gilded Age is often associated in the modern public consciousness with political corruption. This isn't without merit. Machine politics is often at the core of that discussion, and it is what many politicians such as Roscoe Conkling fought for, and what presidents such as Rutherford B. Hayes fought against. In the first months of Hayes' presidency, he signed an executive order banning federal employees from engaging in political activities, according to Miller Center. Conkling, who referred to Hayes as "Rutherfraud B. Hayes" (per NPS), was furious. As explained by The Washington Post, it seemed almost personal between these two men, as Hayes worked to dismantle the power system that Conkling had built, while Conkling referred to Hayes and his supporters as hypocrites and the "carpet knights of politics."

Eventually, Hayes decided to make an example of someone disobeying his executive order and fired Conkling's friend Chester A. Arthur as the head of the New York Customhouse. Conkling, in response, rallied his Stalwarts to block Hayes' appointment of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., into the position (via Miller Center). As his first term was coming to an end, Hayes then made good on his promise and, much to Conkling's almost certain delight, declined to run for a second term (per The White House).

Despite all of this, they did fall in line together on occasion, such as when Conkling supported Hayes against House Democrats attaching riders to bills defunding the U.S Army to weaken their oversight of southern elections (per NPS).

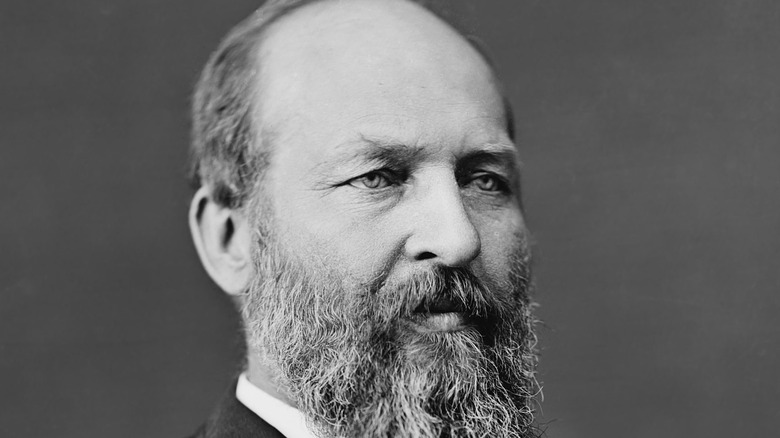

James Garfield needed Conkling on his side to win the presidency

During the election of 1880, the Democratic Party had settled on Gettysburg war hero Winfield Scott Hancock, a U.S. Army General who was perhaps best known for commanding the forces who fought off the Confederates at Pickett's Charge (via History). On the Republican side, the divide within the party had created quite a mess, but ultimately it would be another veteran of the Civil War, a moderate Half Breed, who would be selected by delegates as a compromise candidate: James A. Garfield (via Britannica).

In the months leading up to the Republican National Convention, Roscoe Conkling had thrown his support behind Ulysses S. Grant returning to run for a third term. Behind the scenes of the convention, Conkling's adversaries were succeeding in blocking Grant's nomination (per NPS). After Garfield was selected as the compromise candidate, Garfield realized that he needed the full support of Conkling and his New York machine if he was going to win the state. So, according to PBS, Garfield made the trip to meet and negotiate with Conkling in person, but he never showed up for the initial meeting, meaning Garfield instead had to meet with Chester A. Arthur. While what exactly happened behind closed doors is unknown, but eventually, Conkling and his Stalwarts gave their unenthusiastic support in exchange for what they believed were guarantees over maintaining control of New York patronage ... and eventually, Garfield even offered Arthur to be his vice president (per Washington Post).

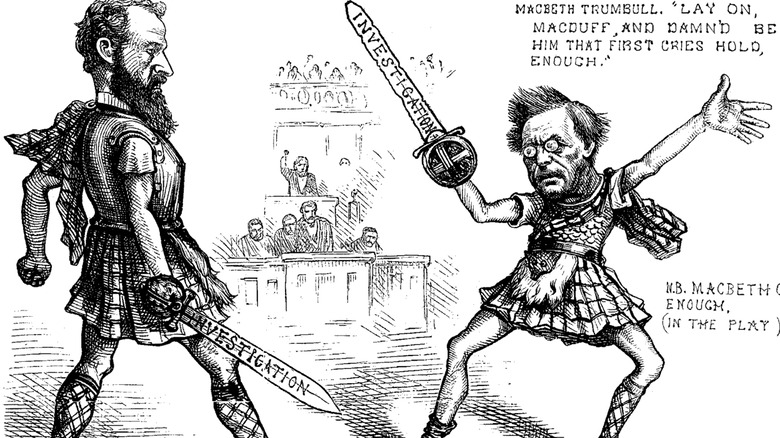

Conkling felt betrayed by Garfield and resigned from the Senate

While James A. Garfield won the electoral college 214 to Winfield Scott Hancock's 155, the popular vote margin nationwide was a mere 10,000 votes (per The White House). Very quickly, and much to Roscoe Conkling's frustration, Garfield very much was his own man as president. For one, many of the supposed promises made behind closed doors between the two men were not being honored by Garfield (per NPS). Their most significant disagreement, though, came over Garfield's unapproved appointment of William Robertson, one of Conkling's rivals who wasn't on his approved list of appointees, to be in charge of the New York Customs House (via The Washington Post). According to the National Park Service, this battle between Garfield and Conkling lasted for months. It became a game of chess between the two, as Garfield viewed this as a way to challenge the patronage system.

Conkling, in return, worked to have the Senate confirm all of the Stalwart-approved nominations but not vote at all on Robertson, which led to Garfield withdrawing all of the rest of his nominations besides Robertson (via The White House). Finally, in May 1881, Conkling (and the other New York Senator) resigned from the Senate in protest of the attacks on the patronage system. Yet, even this was a political game: Conkling hoped that the state legislature would re-elect him to the position, giving Conkling more leverage and authority against Garfield (via Senate.gov). That would ultimately not come to pass.

Garfield's assassination changed Conkling's political trajectory

On the morning of July 2, 1881, not even a year into his presidency, President James Garfield was shot from behind while at the train station preparing to head to Williams College (via Miller Center). A grueling two months would pass before the president finally succumbed to infection and, as a result, Roscoe Conkling's good friend and protégé Chester A. Arthur found himself being sworn in as President of the United States, per Britannica.

At the same time, the death of Garfield changed the political playing field, and Roscoe Conkling, as a result, lost his bid to be reinstated to his Senate seat, bringing a finality to his long and turbulent political career (per Senate.gov). Meanwhile, Conkling's old friend, President Arthur, demonstrated that he was not merely a pawn of the political machine and began to vote against the interests of his fellow Stalwarts; that included, shockingly, his support of the Pendleton Civil Service Act of 1883, which helped dismantle the corruption of the patronage system by incorporating a system based on merit (via Britannica). Conkling and his fellow Stalwarts felt betrayed.

He turned down a Supreme Court seat ... twice

Perhaps one of the more notable tidbits of Roscoe Conkling's long and fascinating career in politics was that he turned down a nomination to the Supreme Court ... twice. The second time was after being rejected from the Senate following Garfield's assassination and, like a good friend and former protégé, President Chester A. Arthur decided to nominate him to the court without first confirming with Conkling that he would accept, according to The Washington Post. Even with the Senate already confirming his appointment, Conkling was already disillusioned by his old friend's presidency and his anti-Stalwart policies. He declined the nomination and returned to practicing law in New York City (per Britannica). Conkling's biographer Donald Barr Chidsey noted that his rejection letter was polite, but made it clear that their friendship had ended (via The Washington Post). According to The Atlantic, this makes Conkling the last person to declined a nomination after being confirmed.

This wasn't the first time that Conkling had declined a nomination either. President Ulysses S. Grant had also nominated him to the Supreme Court years earlier, but Conkling denied the nomination due to the belief that he could be more impactful in his role as Senator (via Lewis & Clark Digital Collections).

A walk in a blizzard led to his death

Conkling would spend the last years of his life practicing law in New York City. As described by WNYC News, it was from these law offices that Conkling emerged into a rare March blizzard in 1888 and, after being offered a ride at an upcharge, decided to make the trek on his own. The city was essentially at a standstill that evening, with the storm's wind gusts approach 75 miles per hour as Conkling made the nearly three-mile voyage by foot (per NPS). In his own writings, Conkling described this walk, stating that he could barely tell where he was going, and that it was completely dark. "[I] was up to my arms in a drift," he wrote and then added, "I came as near giving right up and sinking down there to die as a man can and not do it." It had taken him three hours.

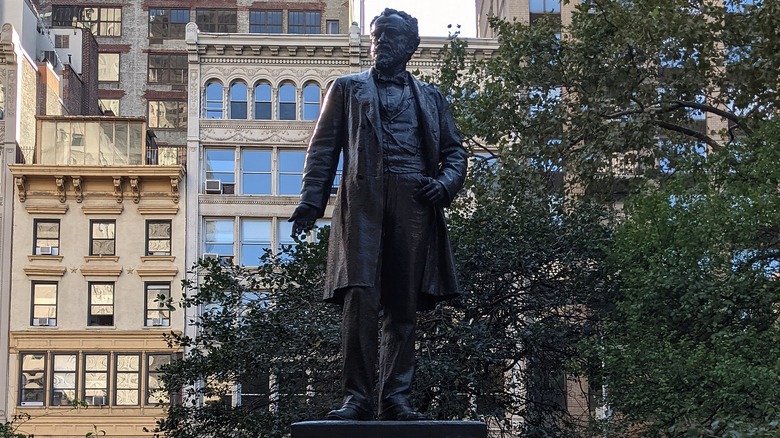

When he arrived home, he fell to the ground and an arriving doctor noted that he had an abscess in his ear. After a few weeks, it was clear that an operation was needed and doctors punctured his skull to release the buildup of fluids, but Conkling soon feel into a coma (per NPS). He died on April 18, 1888. Today in Madison Square Park, a statue of Roscoe Conkling memorializes the complex, combative, and interesting political figure (via WNYC).