A Big Secret Lies Behind Lincoln's Head On Mount Rushmore

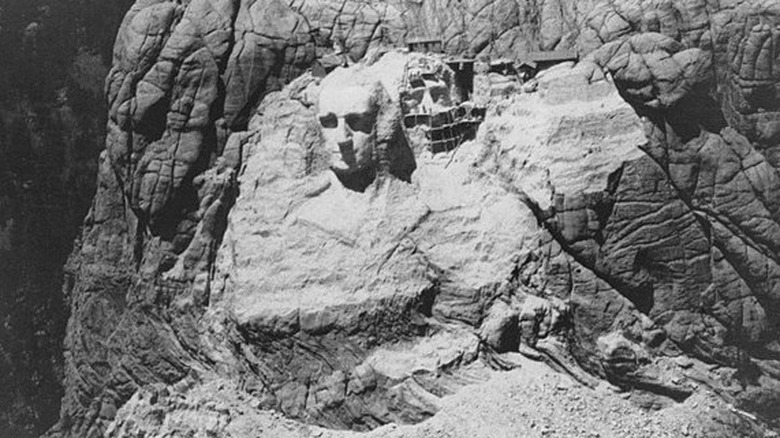

The United States is home to some of the world's most iconic and stunning landmarks. Some of them are natural, such as the majestic Grand Canyon, which stretches for an astonishing 277 miles in length. Others were built by humans, such as the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, and the Lincoln Memorial. Count among the man-made wonders of North America, Mount Rushmore. At the monument, four of America's most iconic presidents — George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, and Teddy Roosevelt — are impressively carved into pure granite in the Black Hills of South Dakota, as the National Park Service (NPS) explains.

For the 2 million people who visit there annually, Mount Rushmore is fascinating and awe-inspiring to behold from the outside, but there's something just as intriguing inside Lincoln's head, envisioned by sculptor Gutzon Borglum when the Rushmore monument was conceived in the 1920s as a repository for the nation's precious documents. Today, few have seen the interior of the space carved behind Honest Abe's likeness, which went unfinished in Borglum's lifetime. Today, it is now in use, less as a tribute to the history of the U.S. but as a space to tell the story of Mount Rushmore to future generations, the presidents memorialized there, and the people who made Mount Rushmore an important part of America's landscape.

Mount Rushmore's history

According to History, the mountain that now holds the Mount Rushmore monument derives its name from Charles E. Rushmore, a lawyer from New York who, in the 19th century, was in the Black Hills to investigate recent gold findings in the region. The area has long been a sacred site of the Lakota Sioux, an indigenous population of the area. The land surrounding what is Mount Rushmore today has seen centuries of conflict between Native Americans and the U.S. federal government, worsened when gold was discovered, such as the Battle of the Little Bighorn and the Massacre at Wounded Knee. Because of this, Mount Rushmore's splendor means something different to some indigenous populations and their ancestral homeland.

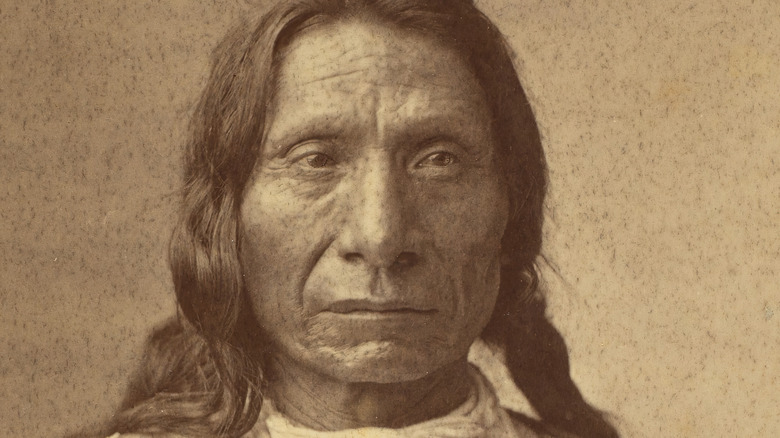

At first, Rushmore, the eastern gold prospector and the monument's namesake, christened the unnamed peak, sitting nearly 6,000 feet above sea level, Rushmore Peak, which later became Rushmore Mountain and then Mount Rushmore. By the 1920s, a similar project to what would one day be Mount Rushmore was proposed with iconic characters of the Old West, including possibly Red Cloud, a Sioux chief (pictured). By 1927, the four presidents we know today were settled on, and Danish sculptor Gutzom Borglum was chosen for the project. With the support of President Calvin Coolidge — not to mention dynamite and powerful new equipment that was required to tackle a project of this size — the work on Mount Rushmore started in October 1927 and for the most part, was finished by the late 1930s.

The hallowed hall of records

Though the final of the four presidential portraits carved into granite at Rushmore, Theodore Roosevelt, was completed in 1939, sculptor Gutzom Borglum died before all the finishing details were taken care of. This work was posthumously done by Borglum's son, Lincoln. Per Black Hills Visitor Magazine, Borglum had originally intended to create a carving at the site, which would detail various events in the nation's history. The issue Borglum found was, given Mount Rushmore's location, getting close enough to read something from a distance was all but impossible, and not without it being so big as to obscure those famous faces — essentially, if Borglum chose to carve words into the mountainside, nobody could have read them.

Borglum's proposed answer was what he saw as an elaborate Hall of Records, that secret chamber mentioned behind Lincoln's head. There, Borglum planned a sort of museum of U.S. history where priceless Americana like the Declaration of Independence would be stored. The goal was to conserve valuable information and context for future generations, but, as mentioned, the Hall of Records was only in construction when Borglum died in 1941. At that point, nothing more than a 70-foot chamber existed where Borglum thought the Hall of Records would be located, and it wasn't until 1998 that a less elaborate, more practical Hall of Records was created, according to the National Park Service.

Today, the Hall of Records contains 16 porcelain panels

This chamber known as the Hall of Records, which is not open to the public and which only a very few have ever seen, doesn't house important documents like the Declaration of Independence, but instead, it's where 16 pieces of porcelain enamel panels are kept. On those porcelain panels is written the story of the Mount Rushmore project, its architect, and of the United States itself, along with the details of each man who worked on the carvings, and why each president was chosen to be immortalized on the mountain.

Though perhaps not as grand as what Borglum planned, the Hall of Records as it now stands is in keeping with this quote from the sculptor, as quoted by The National Park Service. According to the NPS, Borglum said: "You may as well drop a letter into the world's postal service without an address or signature, as to send that carved mountain into history without identification." And though it was not completed in Borglum's lifetime, that type of identification is the role the Mount Rushmore Hall of Records, inside Lincoln's head, fulfills today. Knowing it exists is about as far as any of us will get to visiting the space, however, as it's closed to visitors.