Professional Athletes Who Went To War

For professional athletes who find their careers intersecting with military conflicts, what to do isn't always clear-cut.

Take Joe DiMaggio. He was playing for the Yankees when the U.S. entered World War II, and according to Tinker Air Force Base, it was the same time he was doing some pretty heavy negotiating for a pay increase. Even though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued an official statement saying that the games should go on (and provide some much-needed entertainment and distraction for the nation), DiMaggio's negotiations didn't go unnoticed. Soldiers from Florida's Camp Blanding told him via telegram that he was more than welcome to enlist if the pay raise fell through, and ultimately, that's what he did.

DiMaggio's experience was far from that of the ordinary soldier: When most professional athletes joined the military — even when there was a war going on — their purpose was entertainment. They entertained the troops, boosted the morale of the nation, and at the end of the day, they were mostly kept out of harm's way.

Mostly. Even as DiMaggio played baseball games on the mainland and in Hawaii, others did see active combat. Their stories — like the stories of other, more "ordinary" soldiers — are pretty incredible.

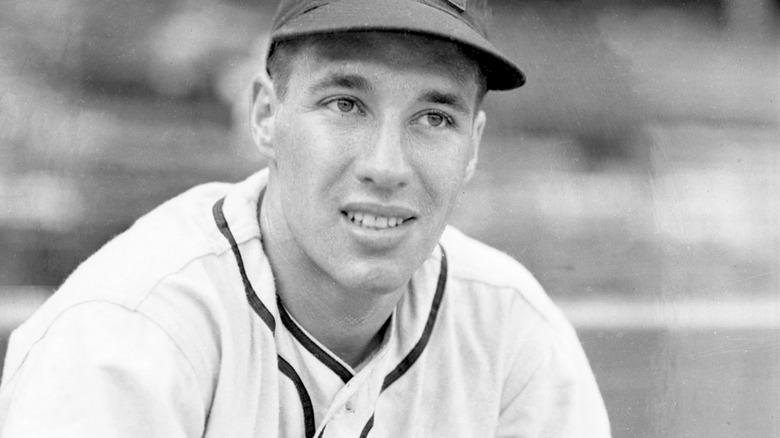

Bob Feller

Bob Feller signed with the Cleveland Indians when he was still in high school. His salary? A dollar, and an autographed ball. According to Major League Baseball, Feller was one of the best pitchers of his era, and although the team had made a ridiculously good choice in hiring the teen, the world changed on Dec. 7, 1941.

That was, of course, Pearl Harbor — and it was also the day Feller was supposed to sign his contract for the 1942 season. He later recalled: "It was about noon; I had the radio on in the car and had just crossed the river into Quad Cities when I got the news. That was it. I had planned on joining the Navy as soon as the war broke out. Everybody knew that we were going to get in it sooner or later, and that was the day" (via ESPN).

Even though he was exempt from the draft for family reasons, Feller became a chief petty officer and was assigned to the USS Alabama as a gun captain. Then? They got dropped into the middle of the action. The Alabama served as a convoy escort in both the North Atlantic and the Pacific, where its crew saw combat, including in the Marshall Islands and the Philippines. In addition to defending aircraft carriers from attacks, they provided support during amphibious assaults and even weathered a typhoon.

Fifteen days after Hiroshima, Feller was transferred to inactive duty and ultimately returned to pick up his professional baseball career (via Military.com).

Bob Kalsu

All-American offensive lineman Bob Kalsu was poised on the edge of a breakout career. It was the late 1960s, he was making a name for himself in Oklahoma, and he was drafted by the Buffalo Bills. He would go on to be their Rookie of the Year, and then, he would go on to the military, where he would find another kind of fame — as the only professional athlete to die in the Vietnam war (via Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund).

As reported by Sports Illustrated, after eight months of training, Kalsu got his orders to head to the front. He shipped out, and his wife wrote to him shortly after he left to tell him the news — she was pregnant.

Kalsu saw her once more — seven months later, for a week's worth of leave. Then, it was back to Vietnam. She was due on July 21, 1970, a day that Kalsu would find himself in the middle of the bloodiest conflict he'd been involved with, this one at the ominously named Firebase Ripcord. With him was Pfc. Nick Fotias, who recalled the moment Kalsu read the letter from home, confirming the baby was coming. A split second later, a mortar landed only a few feet away. Fotias saw everything go dark, and when the darkness faded, he pushed the weight off his chest.

The weight was Kalsu. He was dead, and his family received the news on the same day his son was born: July 23, 1970. He was named James Robert Kalsu Jr.

Bobby Jones

World War II was all-encompassing, and The Augusta Chronicle says that golf stars were getting involved, too, with some of the biggest names holding exhibition events and raising money for the war effort. Bobby Jones — co-founder of the Masters Tournament — started out that way, but after the 1942 Masters, he applied for a commission in the Army Air Forces.

Then 40 years old, Jones had to push for a commission that was something other than ceremonial. Golf Digest quotes him as explaining, "I don't want to be a hoopty-da officer of some camp," and he got his way. He joined up as a captain with the First Fighter Command, was promoted to major with the Ninth Air Force, and by 1943, he was in England.

Months after arriving, it was all-hands-on-deck for D-Day and the Normandy invasion. Jones and his unit were right there for Operation Overlord, among those who stormed the beach on the second day of the incursion. He and his men spent several days on the beach and under fire, and — like many D-Day veterans — would never talk about what he had seen and experienced there. He was discharged in August of that year, and returned to the U.S. and to golf.

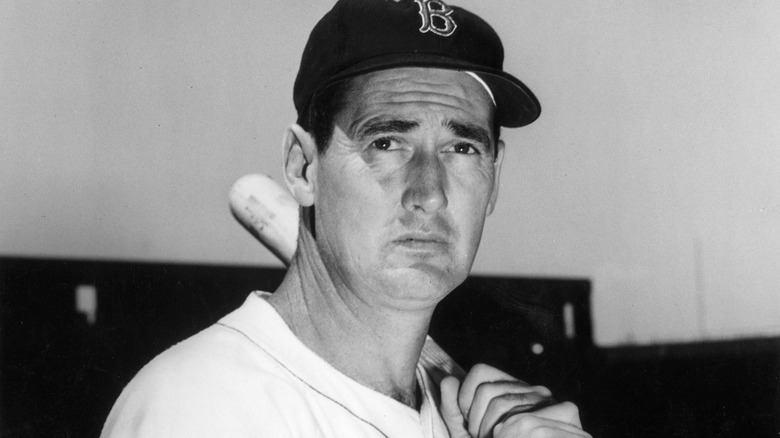

Ted Williams

The word "legend" gets tossed around a lot, but ask anyone from Boston — especially anyone who follows baseball — and Ted Williams is bound to be mentioned. In addition to taking home MVP titles and a whole bunch of other accomplishments most efficiently described as "etc., etc.," Williams also served on active duty during both World War II and Korea.

NBC says that he already had the nickname Teddy Ballgame when he temporarily left baseball for the military, where — according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame — he went to flight school and became part of the elite 10% of students who earned their wings. Between 1942 and 1946, Williams was a part of the U.S. Navy Reserve and saw active duty as a naval aviator.

After the war, he had the chance to apply for a full discharge but opted not to. Instead, Ted Williams signed up for the inactive reserves and returned to baseball and the Red Sox, but just a few years later, he found himself getting a call to return to duty.

So, he did. After attending 1952's spring training, Williams went through a flight school refresher course and then, to the front lines of the Korean War. Boston.com says that he would go on to fly 39 combat missions, including several with future astronaut John Glenn. Although there were close calls — including one crash landing — Williams eventually returned to baseball yet again, after being sent home after developing ear trouble stemming from a bout of pneumonia.

Larry Doby

Jackie Robinson famously broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, and three months later, the Society for American Baseball Research says Larry Doby became the American League's first Black player. Before that, though, Doby played for the Newark Eagles (who were a part of the Negro League) and served in World War II.

Born in South Carolina, Doby had baseball in his blood: His father was a semi-pro player. After losing his father in a tragic accident, the 8-year-old Doby moved with his mother to New Jersey, where he grew up. After high school, college, and some time in the Negro Leagues, he joined the Navy — and was outspoken about the discrimination he faced (via The New York Times).

According to the U.S. Department of Defense, Doby's military service came at the height of the war — from 1943 to 1946. After being stationed in Illinois and California, Doby was sent out to the front lines of the Pacific theater. He was stationed on a Caroline Islands atoll called Ulithi in 1945, and at the time, the base there was prepping for the push into first the Philippines, then Japan. Larry Dobby's service was meaningful for another reason, too: His father wasn't just a baseball player, he had served during World War I.

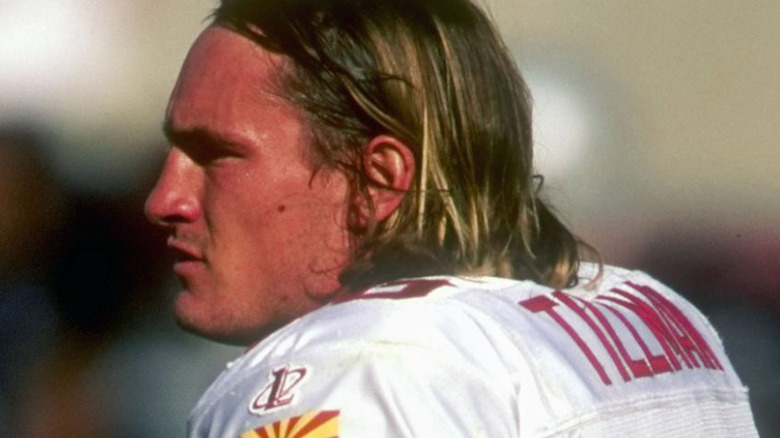

Pat Tillman

When it comes to the military careers of professional athletes, few have been as headline-making or as controversial as that of Pat Tillman's.

Tillman made waves as a college football player, and became a starter for the Arizona Cardinals the same year he was drafted: 1998. He broke records, per History, and he seemed poised on the edge of an award-winning, accolade-filled pro football career when he decided to join the Army.

The Intercept says Tillman's decision was born in the aftermath of 9/11: Tillman's decision was simple and deeply personal. Not only did his brother join him in his enlistment, but he turned his back on both a $3.6 million contract and on all interviews regarding his decision to leave football for the military.

Tillman's military career was very much hands-on: He served in Iraq in 2003 and was deployed in the midst of the rescue of Jessica Lynch — something that he infamously called "a big Public Relations stunt" (via CBS News). In 2004, he was sent to Afghanistan, and there, he was killed — not by the enemy, but by friendly fire.

The fallout was fast, but years later, questions linger. The initial military investigation came with phrases like "gross negligence" and even "criminal intent," leaving many to wonder just what really happened leading up to that day.

Ty Cobb

The U.S. Department of Defense credits Ty Cobb with setting 90 records during his career, which went from 1905 all the way to 1928. There was only a brief time that he wasn't playing, and that was when he enlisted in the Army and was sent to France as a part of the Chemical Corps' Gas and Flame Division.

Cobb explained his decision to enlist: "I feel mean every time I look at a casualty list. I feel I must give up baseball at the close of the season and do my duty by my country in the best way possible."

Cobb was sent to France in November of 1918, and the unit's role was dire stuff. As the National Baseball Hall of Fame explains, Cobb and his unit were the ones pushing through no man's land, dousing enemy trenches with liquid fire and gas bombs. He was one of the instructors, and he would later tell the story of how one of his unit's drills went terribly wrong.

In order to get soldiers used to grabbing and equipping gas masks under pressure, they would be sent into an airtight room and gas would be released. One drill went bad, leading to complete chaos and eight deaths. The division would never see active combat — Armistice came not long after Cobb arrived in France — but Cobb was still so sick from the incident when he returned stateside that he announced his retirement. (He later decided to keep playing.)

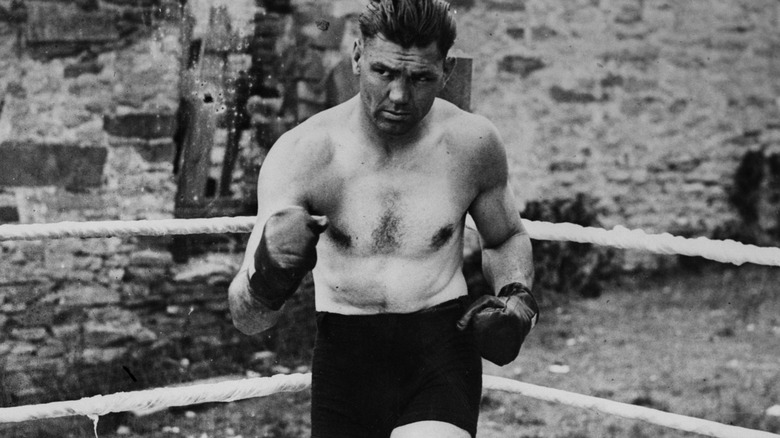

Jack Dempsey

Jack Dempsey's World War II service wasn't just impressive, it was born of a deep-seated need to make amends.

Dempsey was the right age to enlist during World War I, but at the time, he claimed a perfectly legitimate exemption as the sole supporter of his wife, his mother, and his disabled sibling. It happened to be during those years that his boxing career took off, and according to the Veterans Breakfast Club, Dempsey never forgave himself for a 1918 publicity stunt where he was photographed "working" in a Philadelphia shipyard. His shiny shoes and clothes gave away the fact that he wasn't working there, and by the time WWII rolled around, he was determined to make it right.

He was 47 years old when Pearl Harbor happened, and Dempsey joined first the New York National Guard, then the Coast Guard. Initially dumped right back into the world of publicity and morale, Dempsey pushed for active duty. He got it: He was assigned to the USS Arthur Middleton, which was part of the assault on Okinawa.

The U.S. Coast Guard says that the Middleton landed on Okinawa on April 1, 1945. It took until April 4 to offload all the personnel and equipment — amid constant air attacks — and Dempsey was one of the oldest soldiers to set foot on the beach. He would later say, "They branded me a draft dodger in World War I and a hero in World War II. They got it wrong both times."

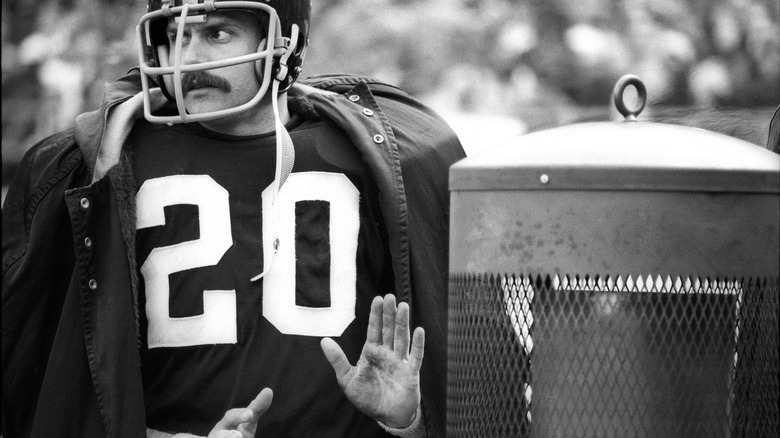

Rocky Bleier

Running back Rocky Bleier was drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1968, and the following year, he was drafted into the Army and sent to Vietnam.

Bleier made it back to football and would become a part of the team famous for the Steel Curtain, but according to We Are The Mighty, he very nearly died overseas. It was August of 1969 when Bleier and the rest of Charlie Company were sent in to back up some of their fellow soldiers, and Bleier was shot in the leg. He made it back to their base, but it wasn't any safer. He described the grenade that was thrown at him: "It ... rolled between my legs, and by the time I jumped to get up, it blew up. I was standing on top of it and it blew up on my right foot, knee, and thigh..."

After an extensive series of surgeries to remove more than 100 pieces of shrapnel, Bleier was told that his football career was over. It would have been easy enough for the Steelers just to cut their losses, but they didn't: They kept him on injured reserve, he was actively playing again by 1972, and ended up joining Pittsburgh for four Super Bowls.

Tim James

Tim James went from the University of Miami to the Miami Heat, and from there, he played three seasons in the NBA. According to ESPN, he was looking ahead to the next thing even before his career in basketball was over: "I wanted to experience a new part of my life. And, I wanted to make a sacrifice."

So, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and was assigned to a division called ODIN (Observe, Detect, Identify, and Neutralize). When The Miami Herald talked to him in 2009 (via the NBA), he was sweltering in the desert more than 100 miles north of Baghdad, where he had been careful to avoid telling his fellow soldiers about his past as a professional basketball player — he didn't want the fuss, and "I didn't want to have a basketball conversation every day." He still carried two basketball cards with him, though: "to drift off on the bad days."

The stories about James' service were hindered a bit by military clearances and permissions, but it wasn't the end of his service either. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs adds that James was later transferred to the 1st Cavalry Division and was honorably discharged in 2011.

Jack Lummus

There's no doubt that had Jack Lummus been born in a different era, his life would have taken a very different path. After getting a scholarship to Baylor, he dropped out near graduation. It was 1941, and Lummus had signed up for the Army Air Corps. Flight school wasn't kind, and after washing out, he hit up the New York Giants and made the team. Still, he played just nine games before Pearl Harbor, and once the U.S. got involved in World War II, he turned back to the military and the Marines.

He entered as a Second Lieutenant and was ultimately assigned to F Company, 2nd Battalion, 27th Marines, 6th Marine Division. That might not ring immediate bells, but The National WWII Museum clarifies: They were sent to lead the assault on Iwo Jima.

Lummus led a charge against pillboxes dotting Kitano Point, which is when he stepped on a landmine. War correspondent Bill Ross would later call his injuries "the spark that ignited the steamroller charge," and his unit plowed ahead even as he was evacuated.

After extensive attempts to repair the damage to his legs — and 18 pints of blood — the 29-year-old Lummus was overheard saying, "I guess the New York Giants have lost the services of a damn good end." And then, he died.

Yogi Berra

Even those who don't follow baseball have heard of Yogi Berra, the catcher who spent most of his wildly impressive, 19-year career behind home plate for the Yankees. Before he was on the receiving end of some serious fastballs, he was under a different kind of fire.

According to the U.S. Navy Memorial, Berra turned 18 when the world was already knee-deep in World War II. He was playing in the minor leagues when he was drafted and ended up joining the Navy. It wasn't long after he got through basic training that he volunteered for a mission that was strictly classified, and set off for more training. What was it?

Berra was deployed as one member of a six-man crew helming a Landing Craft Small Support boat, or LCSS. They were going to be providing support and cover for the Allied troops going ashore at Normandy Beach, and on D-Day, they headed out with the USS Bayfield. Berra's job — when he wasn't at one of the machine guns — was to oversee the boat's weapons and ordinance.

His craft survived D-Day and went on to be deployed elsewhere during the remaining war years. Berra, however, was wounded, and according to the U.S. Department of Defense, received a Purple Heart for his actions at Normandy.

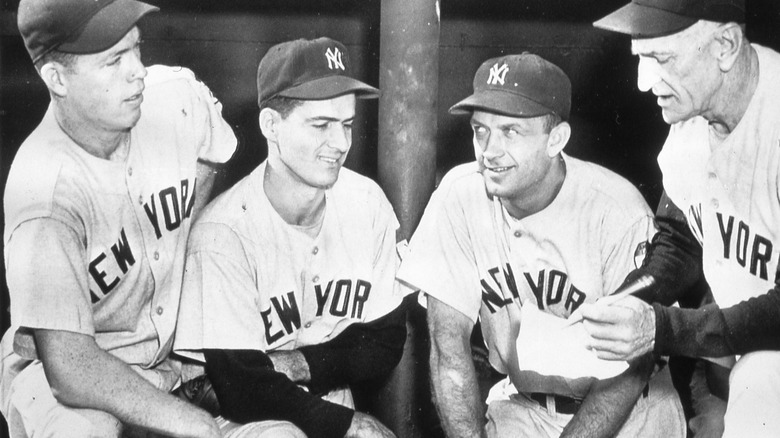

Jerry Coleman

Jerry Coleman (second from left) went to six World Series with the Yankees and went on to become a broadcaster for both the Yankees and the San Diego Padres. Per The New York Times, when he passed away in 2014, the Padres threw open the gates to their stadium so fans could pay their respects.

USA Today quoted him as saying, "The most important thing in my life was not what I did in baseball, but what I did in my service as a Marine in two wars."

The proudest moment of his life was when he was given his pilot's wings: It was April 1, 1944, and he would go on to fly 57 missions in the Pacific (in a Dauntless dive bomber). He returned to the military in 1952, to fly another 63 missions in a single-person fighter.

There were a number of close calls, including a near-collision with a jet and a malfunction that led to his own fighter flipped on the runway before takeoff.

Coleman returned to baseball after being discharged from the military with a slew of awards, medals, and citations, but didn't talk about his service much. There were too many bad memories, including watching the death of his roommate Max Harper. He later explained: "I had to follow him down to see if he got out in a parachute, but there was no chance. I can still see his face today. ... I had an awful lot of heroes, and very good friends. Now, they're all dead."

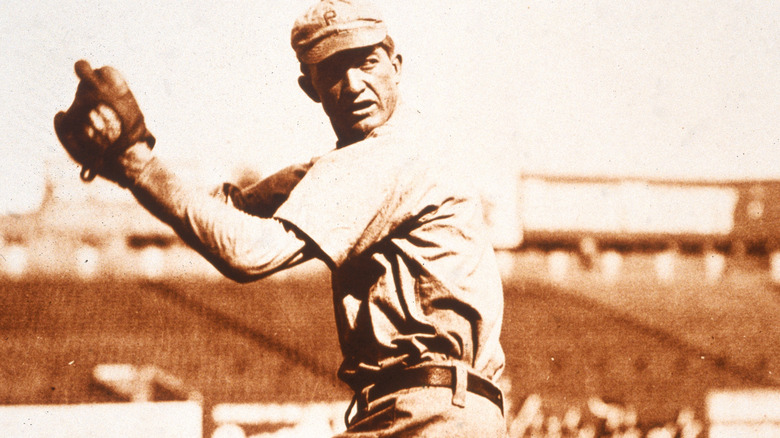

Grover Cleveland Alexander

Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander was lauded as one of the best in the game (via the National Baseball Hall of Fame). He started pitching in Philly in 1911 and was inducted into the game's Hall of Fame in 1938, but in between was World War I.

It wasn't a good time. Alexander was drafted into the Army, became a sergeant, and served on the front lines of France. He was subjected to gas attacks and close-quarter explosions, and when he returned to play for the Chicago Cubs in 1919, he wasn't the same man who had left.

Not only had his pitching arm been severely damaged by high-impact weapons fire, but he was deaf in one ear, peppered with shrapnel and was suffering from what's now called PTSD and struggling with epileptic seizures that were becoming more and more frequent. Still, he continued to pitch and pitch well for a shocking amount of time, only retiring in 1930.

Baseball and World War I historian Jim Leeke wrote "The Best Team Over There: The Untold Story of Grover Cleveland Alexander and the Great War," piecing together the story of Alexander's service (via Project MUSE). He believed that it was a combination of Alexander's post-war struggles and his front-row seat to the horrors of the Spanish flu that left a deep and lasting impact not only on his career, but on the rest of his life.

Tom Landry

Before Tom Landry was one of the most famous coaches for the Dallas Cowboys, he was on the field for both the New York Giants and the New York Yankees. And before that, he served in the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II. According to Lone Star Flight Museum, he flew 30 combat missions — and wasn't the only one of his family to do so.

His beloved older brother, Robert, got there first — and died over the North Atlantic in 1942. A little over a year later, Landry was drafted, went through basic training, then became a pilot just like his brother. And, just like his brother, he stepped into the cockpit of the B-17.

The 19-year-old Landry was sent to England and immediately dispatched on bombing runs into Germany. His first target was an oil refinery in Merseburg, defended by around 600 anti-aircraft guns. Landry later recalled (via HistoryNet): "I never saw anything like that. When we got there, it was just a cloud of black smoke from flak as you headed into the target. ... It was like flying inside a thundercloud."

That run alone was 12 hours in the air, and there were other, even more eventful ones — like their crash-landing in France, which everyone walked away from simply because the plane was so out of fuel, there was nothing left to explode — and missions over the Battle of the Bulge. Landry returned home, married his college sweetheart, and became one of the biggest names in NFL history.