How Germany's Eulenburg Affair Helped Lead To WWI

The generally accepted narrative of what started World War I is pretty universal. After all, ask just about anyone, and if they have any answer to give you about the cause of the First World War, it's probably something to the tune of "the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand." A Serbian national kills a visiting Austro-Hungarian noble, everyone starts pointing fingers at everyone else, and then all of a sudden, a world war breaks out. It makes sense.

But the more you start reading into what actually caused this conflict, the messier the whole narrative becomes. Really, it's much closer to a complex web of somewhat-related events and policies, rather than a single, isolated, catastrophic event (via the Indiana Department of Education).

And it's that complicated mess that proves to be the perfect backdrop for Germany's Eulenburg Affair. Described by historian Norman Domeier as "the first homosexual scare of the 20th century," the Eulenburg Affair was a domestic scandal that would ultimately prove to have much more international effects (worldwide effects, quite literally speaking). It's a little-discussed piece of early 20th-century history, but one that might have been a lot more consequential (and complicated) than it would immediately seem. Here's that story.

Otto von Bismarck and the years before the Eulenburg Affair

To really understand the kind of effects the Eulenburg Affair had on Germany, it's pretty helpful to have a sense of just what was happening in the years prior to it. And given that the Eulenburg Affair is largely said to have taken place from 1906 to 1909 (via "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I"), well, just what was going on in Germany in the late 19th century?

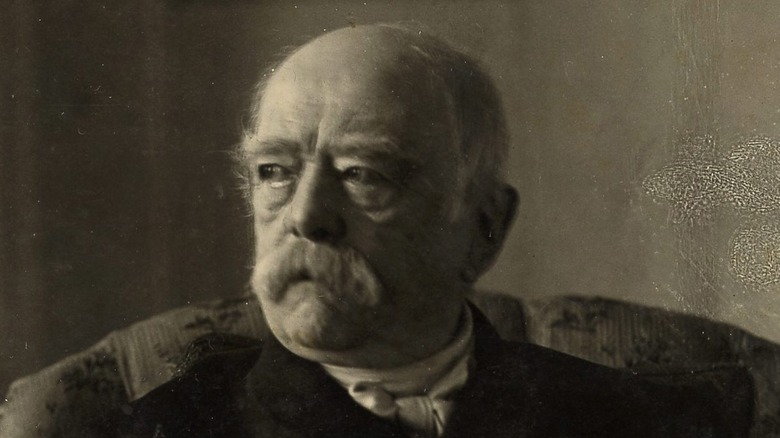

When it comes to events important to this narrative, that can be summed up by looking at one historical figure: Otto von Bismarck. Per History, Bismarck was a hugely important figure in German national identity. Known as the "Iron Chancellor," Bismarck served as chief minister under Prussian king William I, but he was really the power behind the throne. Major reforms and heavy industrialization came to be under his leadership, but maybe more important than that was the credit he's given for the unification of Germany. That's no small task, and on top of that, he made Germany into a force to be reckoned with on the international stage, waging strategic wars and carefully balancing rivalries across Europe.

Though his rule ended in 1890, Reuters explains that he's maintained a type of hero-worship across Germany – a legacy that's actually rather complicated in the modern day. Present-day Germans don't know exactly where he should stand in their history books, but prior to World War II, he was someone to be worshipped and a symbol of nationalistic pride.

The court of Kaiser Wilhelm II

The reign of Otto von Bismarck came to an end in 1890, but, per History, rule under his successors proved to represent a pretty wild swing away from the policies under the Iron Chancellor. Without getting into the full history of the German royal family, it was the grandson of William I, Wilhelm II (or William II) who ultimately ousted Bismarck from power, intending to plot his "New Course," as History describes it. But that course of his ended up fraught with problems.

Over the course of his reign, Wilhelm II was prone to making decisions based purely on his emotions, leading to instances where German foreign policy didn't really make much sense. And that wasn't counting the times when he committed social faux-pas, sometimes offending people on a national scale.

On top of that, according to a review of "The Kaiser and His Court," Wilhelm II effectively set the German court back a few decades. Where Bismarck was known as a man of the people and a capable statesman, Wilhelm modeled his court more like the aristocratic, monarchic organizations of the past – something that would've been considered pretty anachronistic, especially following the changes brought under Bismarck. The old-school, decadent, aristocratic bearings of Wilhelm's court are also mentioned a number of times by Norman Domeier, who then goes on to recount contemporary accounts which linked the aristocracy with effeminacy – a link that would ultimately have quite the dramatic effect on the world at large.

The prince of Eulenburg

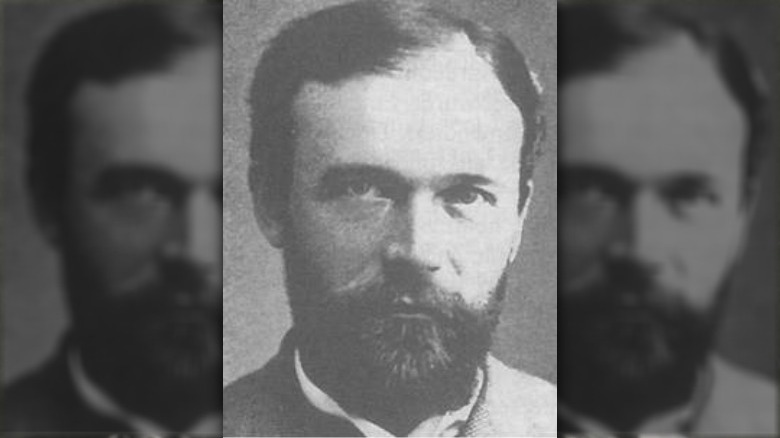

Alright, so it's one thing to start deep diving into the nuances of German politics and society prior to the Eulenburg Affair, but just who was this big affair named after anyway? Well, that would be Philipp Friedrich Karl Alexander Botho, Fürst zu Eulenburg – or, more simply, Philipp, prince of Eulenburg. As is clear by his title, Eulenburg was an aristocrat, but more than that, he was an incredibly influential member of Kaiser Wilhelm II's court. In fact, he was actually a close personal friend of Wilhelm, although Britannica chooses to use the wording "intimate friend." Given his place in this story, the word choice isn't entirely unjustified.

Eulenburg was a member of the Liebenberg Dining Circle (via "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I"), a group of friends who had taken their name from Eulenburg's own castle, and which, in general, came to widely represent an image of posh, aristocratic decadence that had become almost anachronistic in a nation that had been led by Otto von Bismarck. As such, that group fell under heavy scrutiny, but it was the fact that they had close ties to Wilhelm II that really set the stage for scandal. After all, the difference between the connotations of "close" and "intimate" meant a lot, especially in the early 20th century.

Maximilian Harden and Die Zukunft

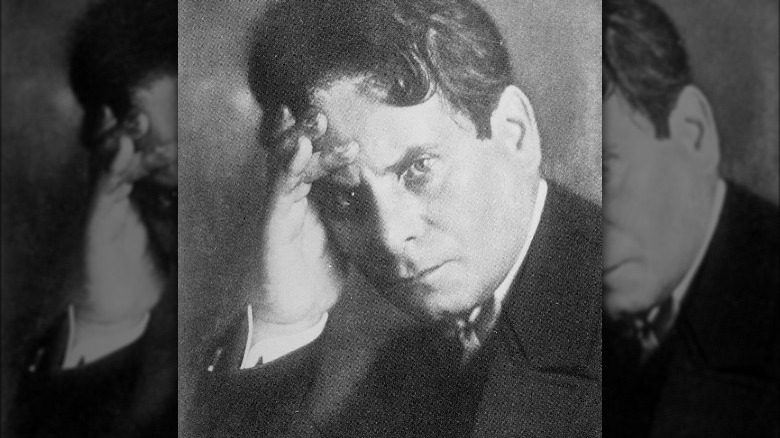

As stated in "The Eulenburg Affair," the political and social situation in Germany had already primed the country for a great crisis of some kind, but despite all of that pre-existing tension, the precarious situation still needed that last thing to push it over the edge. Enter Maximilian Harden.

Already a controversial journalist at the time (via "The Power of Sexology in the Eulenburg Affair, 1906-1909"), Harden happened to get his hands on a handful of letters that had been exchanged between Wilhelm II's close group of friends – Eulenburg included. Per "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I," the writers of those letters referred to each other with intimate nicknames ("sweetie," "old badger," and "sweetheart," to name a few, with the last one allegedly referring to Wilhelm himself). With that information, Harden penned a scathing article and published it in his own magazine, "Die Zukunft," accusing the kaiser and his inner circle of homosexuality, and specifically alleging that Eulenburg was their ringleader.

But it went beyond just accusations of sexuality. Rather, Harden took the chance to slander Eulenburg and his circle, blaming them for every political failing of Wilhelm II up to that point and, essentially, using them as very convenient scapegoats to push his own agenda.

The trials of the Eulenburg Affair

With Maximilian Harden's scathing article regarding Eulenburg and the Wilhelmine court as a whole, it only made sense that trials would follow. And while, according to "German, Jew, Muslim, Gay: The Life and Times of Hugo Marcus," the trials were something of a mess, filled with contradictory testimonies from a supposed expert, they did seem to have an effect in the larger scheme of things.

One of the trials is mentioned fairly often, and it's the one of General Kuno Graf von Moltke, a friend of Eulenburg. As explained in "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I," a large part of Moltke's trial centered around his relationship with his wife; she reportedly beat him on numerous occasions, and he feared her sexual advances. Officially, the testimony put the blame on her for the problems in their marriage, but unofficially, it emasculated one of the highest officials in Wilhelm II's court, something that surprised the public and, most likely, began to sow seeds of doubt in the minds of the people regarding their nation's reputation.

However, it's also worth mentioning that, per Britannica, the accusations toward Eulenburg, at the very least, were never proven. (For that matter, there's never been any evidence proving that Wilhelm II was gay, either, despite him being indirectly implicated in the entire affair). And as for Harden? In case you were curious, Moltke sued him for libel, though he was eventually acquitted.

Sexuality, politics, and morality

Even though the technicalities of the Eulenburg Affair might seem somewhat straightforward – accusations of homosexuality leveled at prominent government officials – the actual implications that color those accusations are quite a bit more complex.

For one, per "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I," the trials weren't just about sexuality, but rather about treason, with Maximilian Harden making claims that Eulenburg and his friends were more likely to (and had) committed treason largely as a result of their sexuality. Little of concrete value actually came from those claims, though they did tie Eulenburg and his circle with a supposedly dangerous political pacifism – one that Harden argued was isolating Wilhelm II from the people, and Germany from the rest of the world. Harden even went so far as to claim that Otto von Bismarck himself had named Eulenburg's group as a danger to national interests, as well as the force behind the downfall of his government in 1890.

But things don't end there because, of course, morals also have to get pulled in. Norman Domeier adds that Harden had a bit more to say on that topic, accusing Eulenburg's circle of being "degenerated" individuals who were surrounding the kaiser with the intention of bringing about not just a political decline from Bismarck's empire, but also a moral one.

The Eulenburg Affair and the First Moroccan Crisis

When it comes to talking about the Eulenburg Affair and its relations to the failings of the Wilhelmine court, it's easy to get caught up in generalizations about political pacifism and bungled international dealings. But there is one event that helps to more concretely define just what Harden was thinking about: the First Moroccan Crisis.

As told by History, in March 1905, Britain and France were settling their imperialist affairs in Africa. But Germany saw that the other two nations were intentionally leaving it out of international affairs. So Wilhelm II decided to take matters into his own hands. Turning his attention toward Morocco, he loudly announced that he recognized the country's independence, doing so with the intention of assuring that Germany could have equal trade rights in Africa. But that didn't quite pan out as expected. Instead, Wilhelm's actions invited suspicion, which in turn invited a whole host of international discussions in Algeciras. At the end of the day, France actually came out on top, with controlling interests in Morocco and an informal alliance with Britain.

As for Germany? According to Norman Domeier, Maximilian Harden spun it this way: Germans wanted to use the conference in Algeciras to project strength and threaten war if things didn't go their way. But, at the behest of Eulenburg and his circle, Wilhelm made it public that he desired peace. Doing so undermined the legitimacy of any shows of strength, and that ultimately led to Germany's embarrassment on the world stage. All of a sudden, the nation was supposedly the laughing stock of the world, and no other nation would take them seriously. At least, that's what Harden claimed.

The Eulenburg Affair and views of masculinity

While it's one thing to sum up the technical events of the Eulenburg Affair, it's another thing entirely to trace how it ultimately affected all of the events to come later (World War I, included). Because this isn't as simple as one nation getting revenge for an assassination, or something like that; it has a lot more to do with the German people's view of themselves, and that's the kind of thing that starts to get a little murkier.

Norman Domeier gets into all the details. In effect, the Eulenburg Affair made all sorts of connections between a bunch of different concepts. Homosexuality got linked to pacifism and aristocracy, but also a whole host of traits that were, at the time, considered effeminate (softness, meekness, and the like). More generally speaking, these were all traits that were seen as weak, and all of a sudden, Germans were concerned that the international community viewed them as a minor power that would back down from every fight.

In contrast, masculinity came to be associated really heavily with things like rampant imperialism and outright violence, as well as power and progress in a very vague sense. Being viewed as a country that was hyper-masculine by this definition also meant being viewed as a major power in international affairs, the kind of power that shouldn't be trifled with. After losses in foreign affairs and being forced to confront their views of themselves, many Germans decided that belligerent masculinity (and a fear of appearing effeminate) was the way forward.

The international community didn't help

While Germany was in the midst of a crisis of self-perception, given that the Eulenburg Affair took place around the turn of the 20th century, this seemingly domestic affair proved to be anything but. In actuality, the rest of the world was watching with interest — and making plenty of comments, some of them pretty provocative.

In general, a number of international observers saw Germany's sudden fall from grace, equating political problems, moral decline, and overall scandal; Wilhelm II, in particular, came to be the target of plenty of scorn (via "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I").

But it was the French who really saw all of this and decided to run with it. Warmongering newspapers explicitly attacked the German sense of masculinity by poking fun at Wilhelm II, painting him as an effeminate leader surrounded by scores of adoring men. (In contrast, they made it well known that Napoleon – their brilliant military man and leader of the past – would've been surrounded by tons of adoring women. Because this was the early 20th century, so, unfortunately, insults looked like that.) Other publications even said that the scandal and scrutiny were merely Germany's just desserts for the earlier Franco-Prussian War, per "The Power of Sexology in the Eulenburg Affair, 1906-1909," and were fortunes reversed, Germans would gladly point and laugh at the French. So in a way, they saw it as justifiable. The Germans, though? They saw it as an unforgivable insult, and one that would have consequences.

Reactionary warmongering

Germany was in crisis mode, to say the least. The German people were questioning everything about their government, national identity, morality, and how all of those things played with each other, and all of a sudden, they were also being insulted by the French. All they knew was that something needed to be done, and that became the perfect place for German imperialists to step in and offer a solution: war.

It shouldn't need to be said that war is a terrible solution to anything, but plenty of arguments in its favor began to fly about. Per "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I," the idea of revitalizing the German military became much more appealing as a way to remind the world that Germany was, in fact, strong and masculine and a force to be reckoned with. Following that logic, war was raised as the perfect vehicle for doing just that; it would allow them to build up their military and give them the chance to, essentially, show off just how tough they were. What was more, due to the connections between aristocracy and pacifism, a war would necessarily drive out those pesky, pacifist nobles; speaking more metaphorically, a war would allow Germany to shed its old skin and emerge as a fully modern nation (you know, the modern nation that many ascribed to the influence of Otto von Bismarck.)

Contemporary journals summed up this feeling, saying, "A fresh and merry war can be a blessing for the people," and all the while, German policy became more and more aggressive and nationalistic as the 1910s approached. If that's not set up for World War I, then what is?

Maybe the Eulenburg Affair was just a symptom of something much larger

In a number of different ways, the Eulenburg Affair was far from an isolated incident. "The Power of Sexology in the Eulenburg Affair, 1906-1909" illustrates that, not only going into the fact that this was an early example of mass media allowing international audiences to snoop on scandals worldwide but also adding that it wasn't the only time accusations of homosexuality had made waves. Europe in general was in the midst of a crisis of masculinity, with various people across the continent giving their two cents about what did or didn't contribute to their concept of true masculinity.

But this concept goes past solely masculinity and sexuality. "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I" also delves into the then-emerging idea of globalization, of international groups being formed that reached across national borders. Maximilian Harden raised the point to try and argue that gay men cared little for nationalistic pride, and while that logic is flawed, the general idea of globalization is, perhaps, still interesting.

European nations were looking to others as a means of deciding where they stood on morals and identity, but also foreign policy. The Indiana Department of Education gives a short list of causes for World War I, and many of them have to do with those international relations, whether the complex mess of alliances or the competitive natures of imperialism and nationalism. In short, the world was just getting a lot smaller, and in some ways, the Eulenburg Affair was potentially only an extension of problems that were already there.