Tragic Details About The Warner Brothers

The company known as Warner Bros. Pictures has been responsible for some of the most iconic films in the history of cinema. From Golden Age classics such as "Casablanca" and "A Streetcar Named Desire" to present-day epics such as the "Harry Potter" franchise and "Joker," the studio shows no signs of slowing down. Yet, how did the company become such a powerhouse? And, better yet, when?

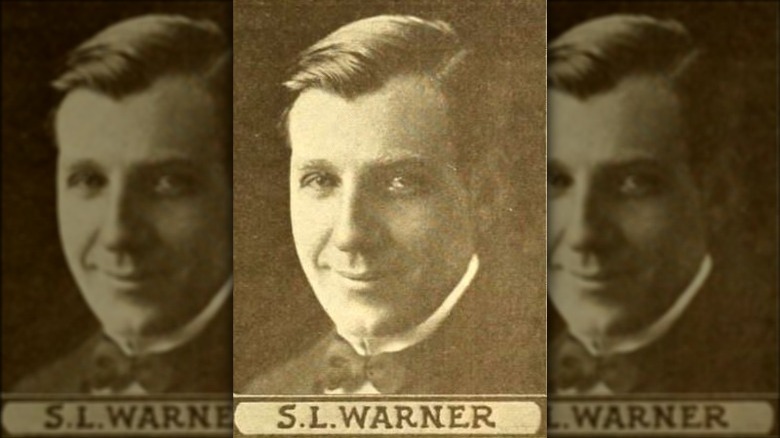

As anyone may have guessed, Warner Bros. Pictures was founded by the Warner brothers themselves: Harry, Albert, Samuel, and Jack Warner. According to Britannica, their last name was actually Eichelbaum, as they were the sons of Polish immigrants who had moved to America. While their company was officially established in 1923, they were grinding for years before then, facing numerous setbacks that made their rise to fame even more noteworthy — but more on that later.

The Warner brothers truly had a rags-to-riches story, overcoming legal obstacles, censorship — and even each other. By the time the final brother, Jack, had died in 1978, the familial bonds that united the men were a mere distant memory. Let's look at the tragic details of the Warner brothers.

The first three brothers were born in Poland, to a poor family

Jack Warner, who later became known as the face of Warner Bros. Pictures, was the only brother of four born outside of Poland, according to the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews. The other three were born in Krasnosielc, a village near Warsaw. Coming from a family of modest means, the Warners' mother, Perla, stayed home looking after her children, while their father, Benjamin, was a shoemaker — in a town that already had quite a few cobblers. Of course, this wasn't the ideal financial situation, so the Warners packed up their bags and left Europe in 1889.

Per Polin, the family first arrived in Baltimore, Maryland, but after finding little success there, they briefly went to Canada, where Benjamin began trading leather. Finally, in 1896, the brood traveled back to America, where they settled down in Youngstown, Ohio. Benjamin put his sons to work early on, and the brothers worked a variety of different jobs. Harry, the eldest, worked as an apprentice at his father's shoe shop and later opened up a bike shop with Albert and Sam. After this venture failed, Albert became a door-to-door salesman, while Sam sought inspiration in the cultural world and worked for various carnivals.

According to Bright Lights Film Journal, Jack, the youngest, wasn't exempt from a hard day's work, and he delivered groceries in their neighborhood. Of course, the boys' profits would go directly into the family's savings.

The Warner brothers could barely afford to buy their first projector

Sam Warner developed a love for the entertainment industry thanks to his carnival job, where he worked as a snake charmer and human shield for different shows. According to Polin, it was during this time that he decided he wanted to be in the biz, too.

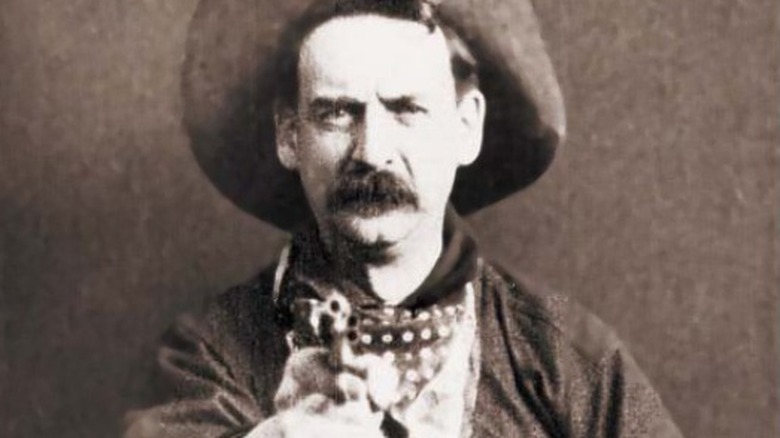

Per Bright Lights Film Journal, Sam abandoned his job at the carnival in 1903, choosing instead to work at a penny arcade in Youngstown, Ohio, where he met a woman selling her projector, a model B Kinetoscope. The 16-year-old, who already had a knack for tinkering with gadgets, was immediately drawn to the item, and after the woman told him she'd also give him a copy of "The Great Train Robbery," Warner knew he had to figure out a way to get his hands on it.

Of course, the teen didn't have the asking price of $1,000, so he marched home to his family to ask for help. Per Bright Lights Film Journal, the Warner brothers put together all the money they had made while their father, Benjamin, sold their family heirloom: a gold watch. With the projector in their hands and one movie to play, the Warners made a tent in their backyard and opened up their first "theater."

Their first few theaters ended in disaster

The Warner brothers' makeshift cinema in the backyard of their Youngstown, Ohio home proved to be short-lived. Per Polin, although surprisingly successful, their neighbors grew annoyed at the theater-going crowds. After nearby residents made one noise complaint to the police, the young businessmen packed up and headed for Niles, the city now known as "the birthplace of Warner Brothers."

Sadly, the Niles theater ended in disaster after a visit from a safety inspector resulted in a fatal explosion for the man thanks to his lit cigar. Yet again, the Warners gathered their equipment and left, and, perhaps due to Sam's background as a carnival worker, they found inspiration to create a "moving" cinema, taking their theater on the road and making stops in nearby towns.

The Warner brothers' final stop came in New Castle, Pennsylvania, where Sam and Albert decided it was finally time to settle down. As explained by Polin, they convinced their older brother, Harry, to sell his bicycle shop back in Youngstown, and they yet again pooled their money together to buy a building in New Castle's city center.

The Warner brothers' first movie theater was a dump

The Warner brothers' opened up their first movie theater in New Castle, Pennsylvania in 1905, dubbing it "The Cascade Movie Palace." According to Polin, the cinema's name didn't exactly match the actual locale. Although The Cascade was elaborately decorated outside with Byzantine arches and Greek columns, the inside was a bit of a dump, with the funeral home nearby loaning their chairs to the Warners. A foul smell permeated the nostrils. It was dirty.

Nevertheless, The Cascade was a success, and perhaps this could be attributed to the brothers knowing how to capitalize on their various talents. As detailed in Bright Lights Film Journal, Harry, the more serious and responsible brother, was the ringleader of the business, handling most of the company's deals. Sam, who was initially the man who came across their first projector, ran it, while Albert was the bookkeeper. Jack, ever the loudmouth, steered the crowd out of their seats at the end of showings. According to the American Film Institute, Jack's official title was a "chaser" — the man responsible for poorly belting out songs.

Business was booming at The Cascade almost immediately. Within a mere few months, the Warners were so successful that they opened up a second cinema in town: The Bijou (via Polin).

Selling their movie theaters made room for another severe setback

When the Warner brothers opened up their first proper movie theater in 1905, they officially founded their Warner Brothers film company — which they later registered in 1923. According to Polin, once they saw the success of their two cinemas in New Castle, Pennsylvania, they realized they could make more money in another avenue of the now-growing film industry: distribution.

In 1907, the Warners sold their two theaters and moved to Pittsburgh. There, they founded their first distribution company, The Duquesne Amusement Supply Company. Much like their cinemas, this business venture proved to be a wise decision, so they opened up another, The Duquesne Film Exchange, in Norfolk, Virginia. Along with launching a movie newspaper, the brothers grew in notoriety, receiving agreements with over 200 producers to be the only ones permitted to distribute their films (via Polin). This is where things started to turn sour. According to Bright Lights Film Journal, the Warners were forced to sell everything they had worked so hard for to Thomas Edison due to his Edison Trust, officially known as the Motion Picture Patents Company.

The Edison Trust, which lasted from 1908 to 1912, was a collection of several businesses that held ownership over film stock and filming equipment. By collecting all the various company patents together, Edison effectively dominated the entire film distribution business. Tragically, this meant the Warners had to, yet again, start from scratch and pivot.

The start-up years of their production company almost left them bankrupt

After losing their distribution companies to the Motion Picture Patents Company, the Warners knew they needed to come up with another business opportunity. Per Polin, that came in the form of their first production company, which Harry opened up in an old steel mill in St. Louis, Missouri. From there, the brothers began releasing movies with Sam and Jack as producers. Sadly, Missouri wasn't exactly considered a cinephile's state, so the Warners moved to New York.

By 1913, the movies that the Warner brothers produced hadn't brought them any financial gain — even in New York. Around this time, producer Sam Goldwyn released Hollywood's first feature-length film, and the Warners, ever observant, packed up their bags (save for Harry and Albert, who stayed in New York to handle their finances), and headed to Los Angeles, where they opened up offices and rented buildings and shooting halls. Hollywood, during this time, was void of any of the glitz and glam it's associated with today. "There were practically no shops and no restaurants," one resident remembered, per Bright Lights Film Journal, while wild animals such as coyotes and deer roamed into Tinseltown for food at night.

As The New York Times recalled decades later, during these early years of their business, Jack would roam the studio after everyone had left, switching off lights that employees had left on as a means to keep their bills as low as possible.

After moving to Hollywood, tension began to rise between the brothers

Along with the literal divide placed between the Warner brothers after Jack and Sam moved to Hollywood, tensions began rising. As detailed by Polin, Jack, the only brother that wasn't born in Poland, began dubbing the other three men "Polish fools" for what he considered was a lack of creativity, while Sam picked up a gambling addiction and subsequent investment in an oil company, draining the studio's funds.

Nevertheless, according to Bright Lights Film Journal, the Warners at least had a knack for "penny-pinching," and eventually, they moved their initial 1918 headquarters from downtown Los Angeles to the center of Hollywood at Sunset Boulevard and Bronson Avenue the following year. The brothers constructed the studio themselves, hiring some of their cast and crew to help out during filming breaks. Of course, finances were still in shambles, but the silver lining came in the form of a German Shepard: Rin-Tin-Tin.

Rin-Tin-Tin came to Tinseltown by way of a former army corporal who rescued him during World War I. With the war over, the man taught the dog a variety of different tricks, and by 1923, he crossed paths with the Warners. Per Bright Lights Film Journal, the pooch starred in more than 20 films during the 1920s and became one of the decade's most profitable stars, saving the Warners from financial ruin. He'd later be dubbed "the Mortgage Lifter" by Jack himself.

Their first great success came with a devastating tragedy

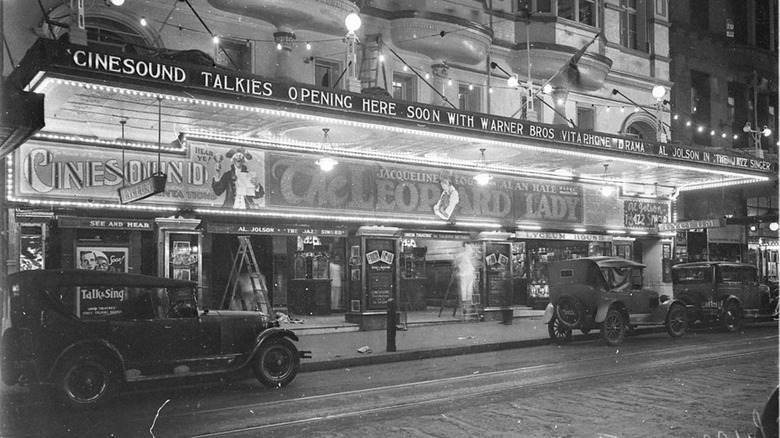

Although the success of A-list pup Rin-Tin-Tin helped dig the Warner brothers out of debt, times were still rough. According to Polin, competition in the film industry was suddenly growing, and the desperate Warners invested the little money they had left into the radio — a new technology. By 1925, they officially made their mark in the new industry by starting one of the first three radio stations in Los Angeles.

Sam, the technologically innovative brother (who after all had the initial idea to purchase their first projector), suddenly saw the benefit of sound in entertainment. He came across Bell Labs, a research group inventing a sound system called the Vitaphone that allowed for dialogue to be synchronized with visual film images (via Culture.Pl). When Sam approached Harry about the product, he reportedly quipped, "Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?!"

Regardless, the Warners ultimately invested in the Vitaphone, becoming co-creators of the patent. By 1927, they released the first-ever film with synchronized dialogue: "The Jazz Singer." Sadly, per Bright Lights Film Journal, Sam suffered from horrible headaches that were later revealed to be a sinus infection. As he put off any treatment due to the production of "The Jazz Singer," his illness got worse, eventually spreading to his brain. After four failed surgeries, Sam Warner died on the operating table at 39 — the day before the film's premiere in New York, per Polin.

After the death of Sam Warner, the brothers weren't unified anymore

The Warner brothers faced a brutal blow with Sam's death. As if that wasn't enough, they were delivered even more shattering news within the next two years. According to Polin, the first ever Oscars were held in 1929, and although one would think the first-ever movie with synchronized sound and dialogue would get nominated, the Academy Awards snubbed "The Jazz Singer" since they believed the flick had an unfair advantage in a sea of silent movies. Instead, the Warners settled for a "special" Oscar for technical innovation.

Besides the professional cold shoulder, the brothers were bickering behind closed doors, too. As revealed by Bright Lights Film Journal, after Sam's untimely passing, the rivalry between the men grew, particularly between Harry and Jack. Harry, the eldest brother, was known for his quiet reserve and professionalism, while Jack was the entertainer of the family, always craving attention. According to "The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution" (via Bright Lights Film Journal), Jack's son, Jack Jr., once claimed, "I think Jack would have shared power willingly with Sam," adding, "And, Sam would have been able to mediate between Jack and Harry."

After Sam's death, Jack was the only brother left in Hollywood, as Harry and Albert ran their finances from New York, per Polin. Along with the physical distance between the men, Jack was also estranging himself from them, running the day-to-day operations of their studio all by himself.

They had to fight the Hays Code, established in 1930

After the premiere of 1927's "The Jazz Singer," the Warner brothers experienced a brief period of financial success. According to Bright Lights Film Journal, the brothers' combined salaries were $100,000 before the film's release, yet after gaining the respect of their peers, that number skyrocketed to $500,000 a year.

Unfortunately, Tinseltown was changing. In 1930, the Motion Picture Production Code (better known as the Hays Code) was established, spelling disaster for production companies — the Warners included. "The Hays Code was this self-imposed industry set of guidelines for all the motion pictures that were released between 1934 and 1968," explained curator Chelsey O'Brien to ACMI, adding that the code prohibited any sexually suggestive content and profanity on camera. As it turned out, movies from pre-code Hollywood were racy and indulgent, and with the Wall Street Crash of 1929 emptying movie-goers' pockets, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America wanted to attract the masses with these edgy films.

So, how did the Warners get around the Hays Code? Better yet, how did they become known for their gangster-centric flicks during this time? Per Bright Lights Film Journal, the Warners claimed that their movies showed audiences the risks of a life of crime. As explained by the American Film Institute, during their release of 1931's "The Public Enemy," Harry declared that the movie's message was the following: "Crime does not pay."

Their stars weren't exactly happy with how they ran their business

By the 1930s, Warner Bros. had finally become a respected production company. However, the brothers had also grown tough in their industry, projecting this rigorous obsession with success onto their most prized stars and working them day and night (via Bright Lights Film Journal).

As detailed in "Hollywood and the Great Depression," Old Hollywood stars had to follow countless rules while signed to a major production company, including the clause that they couldn't quit or work for competitors. Some stars grew fed up with these standards, such as Bette Davis, who filed a lawsuit against the Warners and wanted out of her contract. Unfortunately, she lost (via Bright Lights Film Journal).

More A-listers rose to fight the Warners, but it's Olivia de Havilland's takedown of the studio system that will forever go down in Hollywood history. When she was still a minor, de Havilland signed a contract with Warner Bros. that bound her to the company for seven years, per The Hollywood Reporter. However, a clause of this agreement stated that if the star could not work, her contract would extend. De Havilland, who missed six months, was not free until she filmed the hours owed to the brothers, so she sued them in a two-year court case (via Bright Lights Film Journal). Miraculously, the starlet won, effectively changing the studio system in what would become known as the De Havilland Law in 1943.

Things went downhill after Albert Warner signed the Waldorf Statement

Although Warner Bros. saw great success as one of the leading production companies during the Great Depression, by the time the 1940s came around, their influence on the industry was beginning to decline. In 1947, Albert Warner acted on behalf of his brothers and signed the Waldorf Statement, a document that Polin describes as being responsible, in part, for "the mass layoffs of those suspected of left-wing beliefs." While none of the brothers interjected, Jack began to resent his position within the company and yearned for more power.

With the arrival of a new decade in the '50s, Albert began craving retirement, yet he could not sell his shares unless Jack and Harry did, too. Thankfully, Jack stepped in with a buyer willing to offer $22 million to the men for their combined 800,000 shares of stock, per Bright Lights Film Journal. In May 1956, the brothers finally sold their company. Suddenly, Albert and Harry realized to their horror that their brother had made a separate deal: he bought 200,000 shares worth of their stock back, becoming the company's largest stockholder and, effectively, president.

According to Polin, when Harry found out about Jack's conniving "double-cross," he had a heart attack, followed by a brain hemorrhage.

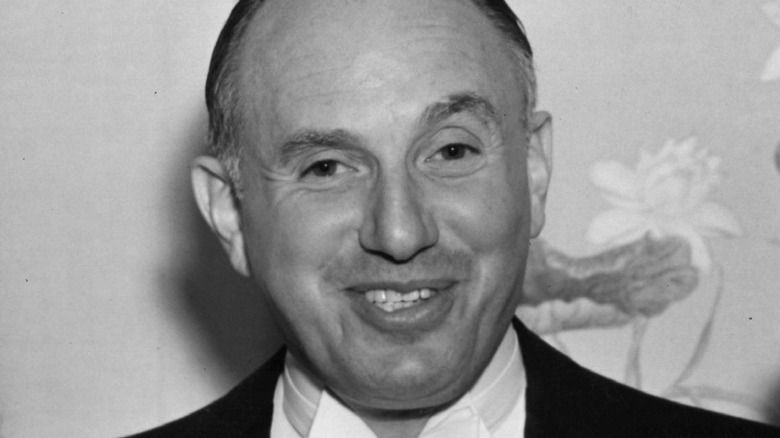

Albert and Jack Warner never spoke again after Harry's death

After Jack took complete control of Warner Bros. in 1956, neither Harry nor Albert ever spoke to him again. According to "The Brothers Warner: The Intimate Story of a Hollywood Studio Family Dynasty" (via Bright Lights Film Journal), when Harry died of cerebral occlusion two years later, his wife, Rhea, declared, "Harry didn't die. Jack killed him."

Per Polin, Jack wasn't welcome to attend his elder brother's funeral — although it begs the question: Would he even have come? "I didn't give a s**t about Harry," he declared to guests at his vacation home at the time, according to the book "Clown Prince of Hollywood: The Antic Life and Times of Jack L. Warner" (via Bright Lights Film Journal). Picking up a letter, he then cruelly quipped, "But hey, look at this. It's a letter of condolence from President Eisenhower. Ain't that something?" Having severed all ties to his family, Jack began spending more time in his luxury villa in Cap d'Antibes, France. Although he finally succeeded in claiming what he believed was his rightful title to the Warner Bros. throne, he was alone.

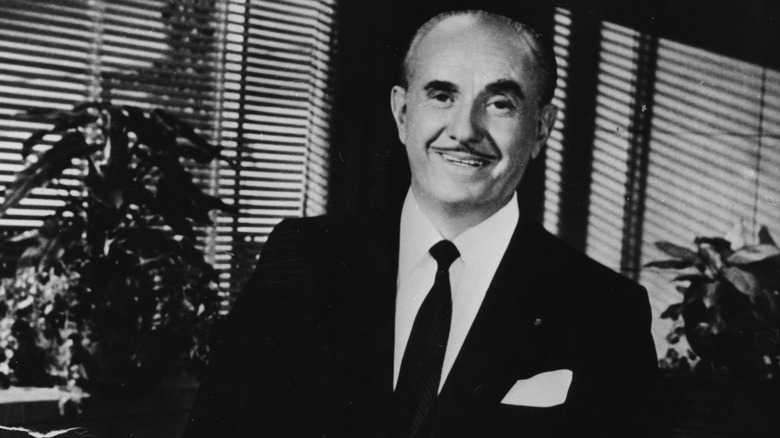

Ironically, the studio began floundering under Jack's ownership, and in 1966, he sold it to Seven Arts Productions. Jack and Albert never spoke again, the latter dying in 1967. At long last, Jack Warner himself passed in 1978. According to The Washington Post, he was considered the final first-generation film mogul.