The True Story Of What Happened The First Time The U.S. Invaded Korea

On June 27, 1950, the United States invaded Korea and the U.S. entered the Korean War. But one of the most bizarre things about the Korean War is that many people don't remember that this actually wasn't the first time the United States invaded Korea. Almost a century earlier, the United States decided that it couldn't tolerate the Kingdom of Korea's unwillingness to trade with the Western world and decided to push the concept of open trade by force, according to The Korea Times.

In the 1860s, German businessman Ernst Oppert tried to grave rob the father of Heungseon Daewongun, the regent of the Joseon Dynasty, in order to extort the country into open trade with the West, reports The Korea Times. Although this plot failed, it's demonstrative of the lengths that Westerners were willing to go to in order to push a nation into economic relations.

Within a decade, the United States followed the lead of the German businessman and another French invasion of Korea in an attempt to establish trade. But the first time around, what was known as the Korea Expedition proved that extorting economic relations wasn't going to be as easy as once thought. This is the true story of what happened the first time the U.S. invaded Korea.

The Backdrop: Isolationism in the Joseon Dynasty

The Joseon Dynasty, also known as the Chosŏn Dynasty, took control over the Korean Peninsula after the fall of the Goryeo Dynasty in 1392. And for over 500 years, until Japan occupied Korea in 1910, the Joseon Dynasty maintained its rule over Korea, writes ThoughtCo.

By the end of the 16th century, the Joseon Dynasty took on more and more of an isolationist position. According to David William Kim's book "Daesoon Jinrihoe in Modern Korea," other than infrequent interactions with the Chinese emperors of the Qing dynasty and some trade occurring with Japan via the Tsushima island, Korea remained relatively shut away from the outside world.

According to "Korea" by Michael J. Seth, the Joseon Dynasty was given the nickname the "Hermit Kingdom" by Westerners due to its isolationism. Residents of the Kingdom of Korea were also reportedly "forbidden to travel abroad except on diplomatic missions to China or Japan."

However, there was still occasional outside contact. According to Kim's "Daesoon Jinrihoe in Modern Korea," foreign ideas entered the country through Korean envoy missions to the Qing court and after Western Catholic missionaries reached China and Japan in the 16th century, which "was done by stealth, either via the China-North Korean border or the Yellow Sea."

The General Sherman goes missing

In August 1866, the USS General Sherman, a ship loaded with weapons, entered Korean waters and traveled to Pyongyang via the Taedong River. According to "A Concise History of Modern Korea" by Michael J. Seth, the merchant ship carried a crew of American, Malay, British, and Chinese people and was reportedly seeking to open trade, despite knowing that Korea was closed to trading with Western countries.

As the General Sherman sailed up the Taedong River, the crew was repeatedly told by emissaries from the Kingdom of Korea that there wasn't going to be any trade and that they should leave immediately. Ignoring this, the crew shot at the crowd on the riverbanks, burned down some boats, and continued to make its way upriver. C. Douglas Sterner writes in "Shinmiyango" that there was little concern over whether or not the Korean people actually wanted to trade with them. Some of the crew boasted that if the Korean people didn't want to trade, "they would loot the cities and return with Korean gold and other valuables."

Within a few days, the General Sherman got caught along the way in a receding tide and became stuck in a sandbar. Seizing an opportunity, the Korean government ordered the General Sherman to be destroyed, writes Paul Edwards in "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War." After the General Sherman was set on fire, the entire crew was captured and massacred.

Pushing for an explanation

After the General Sherman disappeared in Korean waters, the United States government demanded an explanation. But according to "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War," the U.S. government was told that the ship was wrecked in a sudden storm, despite the fact that the French "reported seeing what was left of the burned vessel." In 1867, the U.S. sent another ship to Korea to investigate the disappearance of the General Sherman, but the Korean government was largely unwilling to speak with American officials and the ship returned to the United States without any information. The following year, another ship was sent to Korea to investigate, but once again returned with little to no information.

But according to "Project Eagle" by Robert S. Kim, it's unclear why the American government needed an explanation so badly. Although the ship was a former Confederate blockade runner, known then as the Princess Royal, it had been sold to a British firm in Tianjin, China making it a commercial vessel owned by British people, rather than a U.S. Navy ship. According to "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War," the majority of the people on board were also Malay and Chinese, yet still "America took offense, claimed the ship as its own, and demanded an explanation as to what happened."

Frederick Low's diplomatic delegation

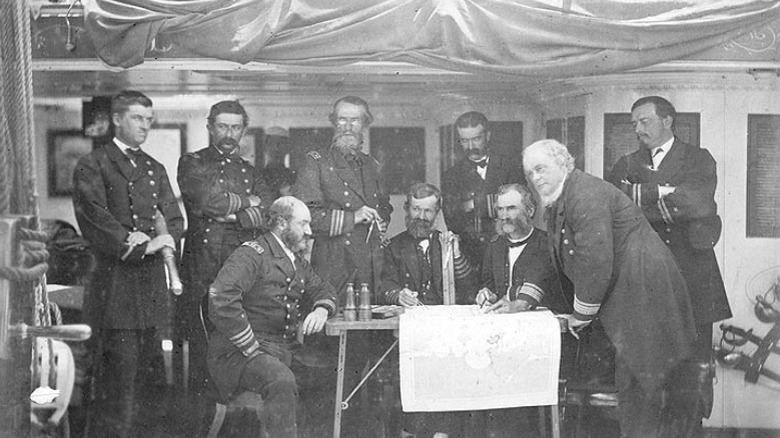

After several failed attempts to determine what happened to the General Sherman, the United States decided to send an expedition to Korea in 1871. According to "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War," this expedition had three goals: to report "a full account of what happened to the General Sherman," to establish "a treaty protecting American seamen shipwrecked in Korea," and make "an agreement for open trade" with Korean officials.

The new Minister to China, Frederick Low, was assigned to head the delegation and was told to seek open trade "should the opportunity seem favorable," per Penn History Review. However, the principal aim of the mission was to secure protection for shipwrecked seamen and Low was cautioned to "avoid a conflict by force unless it cannot be avoided without dishonor."

Low wasn't optimistic about the trip, but after reaching the Harbor of Nagasaki, he notified the Zongli Yamen of the Qing dynasty, which was the governmental office in charge of foreign policy, of his expedition into Korea on March 17, 1871. China, aware of the situation, informed the Joseon Dynasty of the American expedition. The Korean government responded to China, asking if China could help them evade conflict by convincing the U.S. to cancel Low's mission. But because the Korean government forbade direct communication with the Americans, Low didn't get the message and assumed that they were to be peacefully welcomed. He set sail for the Korean Peninsula.

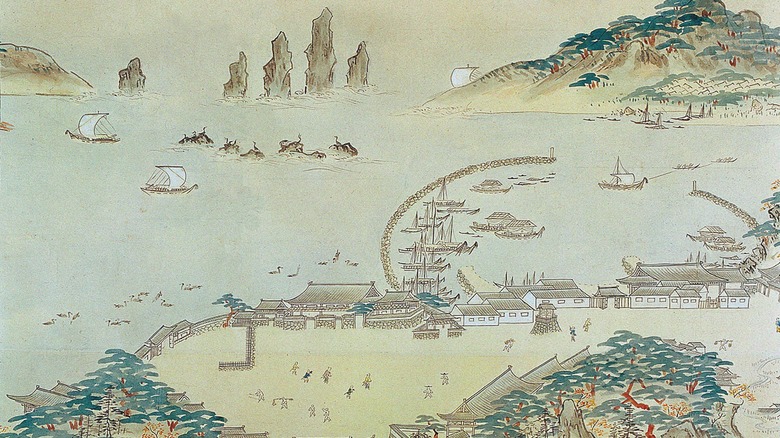

Entering Korean waters

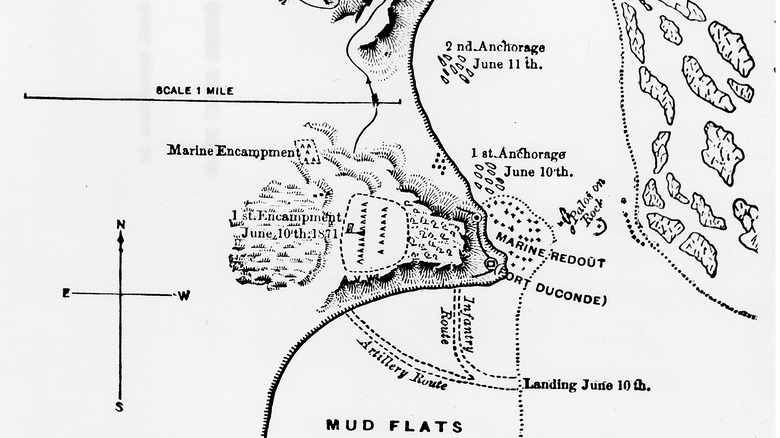

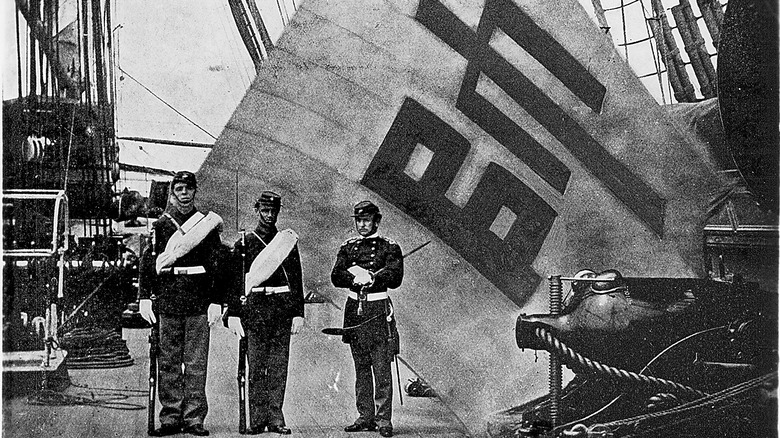

Frederick Low set sail on a military expedition to Korea with five ships, led by the U.S.S. Colorado, known as the Korean Expedition. Edwards writes in "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War" that the force of this fleet was "immense for the time, consisting of 85 cannon and 1,230 Marines and sailors."

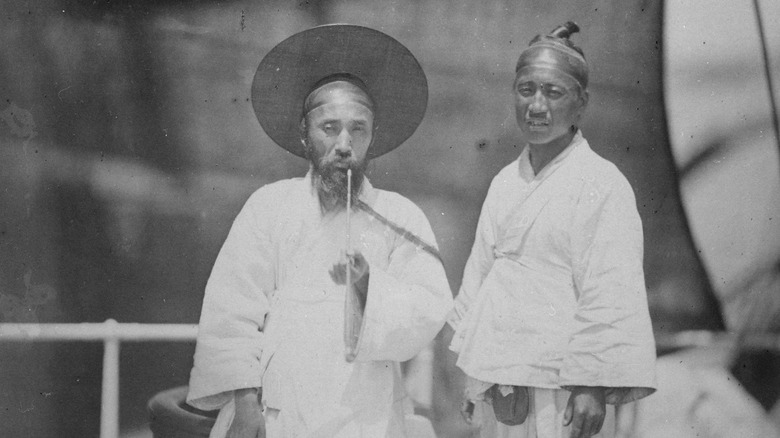

The fleet anchored near the island of Wolmi-do near Inchon harbor on May 23, 1871. The crew undocked and began to explore the area, coming into contact with the citizens of Wolmi-do. Their arrival was also noted by Korean officials, who let them know that communication from the Korean government would be arriving soon. By May 30, the fleet had arrived at Changyak on the banks of the Yomha River, which led to the Han River. There, they were met by three Korean officials, who told them that although the Joseon Dynasty hoped to maintain amicable relations with the United States, they had no intention of trading or forming treaties with the Americans.

Low and his assistants let the officials know that they planned to continue sailing to scope out the riverway and the Korean emissaries reportedly left without commenting on this intention. Penn History Review writes that this was taken as "implicit approval for Low's explorations." However, their silence was actually a refusal, and any movement of a foreign ship into the Han River was seen as an act of war, per "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War."

Bombardment on the bend

The Korean Expedition continued up the Han River, led by two gunboats and four small launches. But just a few days into its journey, as the American forces reached the Sondolmok bend in the river, shots were fired on the Americans from the forts along the river, and a hail of gunfire soon erupted from both sides, per Penn History Review. According to "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War," although it seemed as though Korean forces had an advantage due to their high ground, they were soon overwhelmed by the Americans' firepower.

Although the firefight only lasted about 15 minutes, according to "Shinmiyango," Admiral John Rodgers on the Colorado decided to prepare for a ground assault because they were unaware that they'd technically launched an invasion. Frederick Low managed to convince Rodgers to delay the ground invasion and they agreed to set aside 10 days during which they would wait for the Korean government to apologize for the bombardment.

If they didn't receive an apology, the Korean Expedition planned to launch an assault on Ganghwa Island. But as Penn History Review notes, the American forces were likely feigning ignorance and weren't as innocent as they put on. A Western newspaper in China reported that the American forces ignored numerous warning signs along their way, including a demonstration by 2,000 soldiers.

Communicating back and forth

The decision to issue a 10-day ultimatum was largely a ploy on Frederick Low's part in order to allow for the tide of the Han River to literally turn and make an escape route for the Americans, per Penn History Review. Over those 10 days, the American and Korean forces did communicate back and forth as Korean forces attempted to reconcile the situation.

Bak Gyusu, the local governor who was responsible for ordering the destruction of the General Sherman, first sent a letter to the American forces on June 4. According to Penn History Review, the messages were sent back and forth via a pole erected in the mud flats near where the American ships were anchored. As a last-ditch effort, one final message was sent by a ship with a white flag to Low.

However, Paul Edward writes in "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War" that this message didn't contain an apology and instead maintained that "according to international law the Americans had invaded their sovereign territory and [the Korean people] had every right to defend it." Low reached out to the Korean government again on June 7, suggesting that without an apology military action would be imminent. And with no apology offered by the morning of June 10, the Korean Expedition prepared for their ground assault.

Battle of Ganghwa

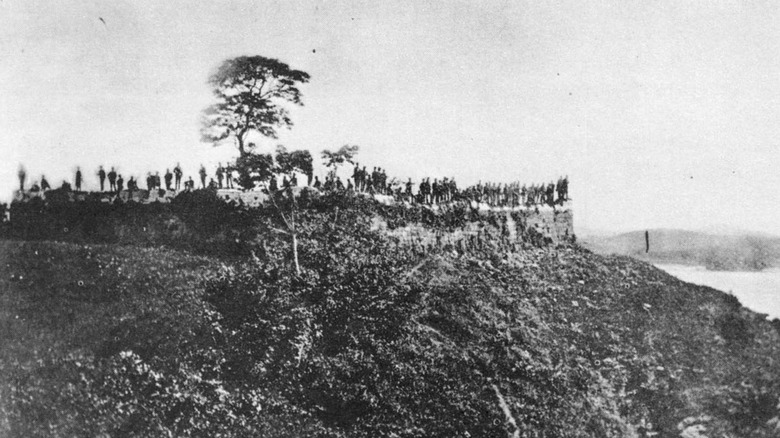

Around 10 a.m. on Saturday, June 10, 1871, the USS Palos and Monocacy set off toward the Kanghwa Strait, bringing 22 smaller boats with them full of Marines and Navy soldiers, according to "Shinmiyango." As they advanced, they captured and burned six villages and five small forts until they reached Gwangseongbo Fortress, from where they had originally been fired upon, according to "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War."

The battle over Gwangseongbo Fortress lasted through Sunday morning. As the American invaders advanced on the fortress and the Korean soldiers ran out of ammunition, they began fighting with swords, rocks, and spears. When General Oh Choe-yon was killed by Marine Private James Dougherty, the Korean soldiers started to pull back from the fortress. But as they ran for the river, Marines shot at them with Remington rifles, "kill[ing] all but a few who managed to escape," according to "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War."

After taking over the Gwangseongbo Fortress, the American forces renamed it Fort McKee after one of their killed men, despite the fact that little remained of the fortress other than rubble and bodies. Meanwhile, when reporting back on the Korean Expedition to the Secretary of State, Frederick Low claimed that "he had made every effort to resolve the dispute amicably, and resorted to violence only as a last resort," per Penn History Review.

The US withdraws

After imprisoning 20 Koreans, the American forces reached out once more to the Korean government. This time, they stated that if the Koreans agreed not to fight against them anymore, their people would be returned to them, according to "Shinmiyango." But per the Association for Asian Research, Korean officials reportedly turned down the offer to negotiate, stating that the "POWs were cowards" and would face consequences once returned. Frederick Low was "welcome to keep the wounded prisoners."

Unable to use them as a bargaining chip, Low released the imprisoned Korean people and on July 3, the Korean Expedition turned around and started sailing back to China, per "Shinmiyango." Seth writes in "A Concise History of Modern Korea" that after the Battle of Ganghwa, Low and Admiral John Rodgers decided to withdraw after being frustrated by the Korean government's refusal to negotiate. Stone signs were even displayed that read "Western barbarians invade our land. If we do not fight we must then appease them. To urge appeasement is to betray the nation."

Edwards writes in "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War" that the Americans were told what happened to the General Sherman and after being offered nothing more, they decided to retreat. Even President Ulysses S. Grant, in his annual address to Congress, avoided mentioning that the Korean Expedition had ultimately failed, stating instead that "the expedition returned, finding it impracticable under the circumstances to conclude the desired convention," per Penn History Review.

Hundreds left dead

The Battle of Ganghwa was one of the bloodiest conflicts between the United States and an Asian country at the time, and according to Penn History Review, the battle "inflicted more casualties on Asian peoples than any other American military action until the Philippine uprising of 1899." "Shinmiyango" writes that at least 243 Korean people were killed in the Battle of Ganghwa in addition to the 20 wounded captives. Meanwhile, three Americans were killed and 10 were wounded.

After the American forces retreated from Korean waters, the Kingdom of Korea "officially maintained a state of war against the Americans for the next 10 years" since there was no treaty made after what was considered to be an official act of war, Edwards writes in "Unusual Footnotes to the Korean War." Until Japan forcibly ended Korea's isolationism five years later, the Korean government refused to deal with the Americans.

Falling to another colonizer

It wasn't long before another colonizer decided to use a similar tactic to persuade Korea to open trade. According to "A Concise History of Modern Korea," the Empire of Japan considered provoking an incident that might lead to an invasion of Korea in 1873, but they ultimately decided against this. Instead, the country decided to use violence to force Korea into open diplomatic and trade relations. In May 1875, two warships were sent by the Empire of Japan to the Kingdom of Korea to sail along the coast and survey the waters. When they reached Kanghwa Island, they were fired upon, just as the Americans had been. After returning fire and overrunning a fort on a small island, additional warships were sent to Busan "with the excuse of protecting the Japanese residents there."

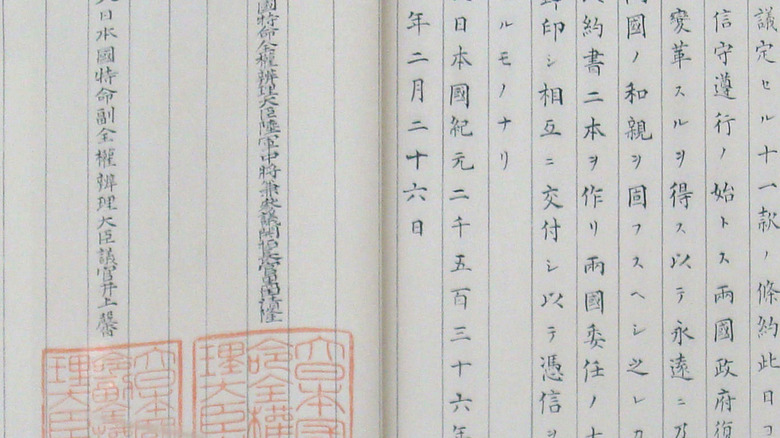

In February 1876, a large military force arrived on Kanghwa Island, demanding an apology for the attack on Japanese ships. As part of the apology, Korea was to open diplomatic and trade relations with Japan. Otherwise, the Japanese fleet threatened to bombard Seoul, writes the Association for Asian Research.

This time, the Kingdom of Korea was forced to concede and the Treaty of Kanghwa was signed with Japan in February 1876, per "A Concise History of Modern Korea." And within 10 years, the United States had its own trade agreement established through the Joseon–United States Treaty of 1882, which Korean Quarterly writes was Korea's first treaty with a Western nation.