Can A Roman Catholic Ever Inherit The British Throne?

The death of Queen Elizabeth II on September 8 left people around the world asking a lot of questions: What happens now? What happens now that Charles II is now king? What happens at a royal funeral? Can people give gifts or tributes? The truth is, it's been quite some time since the United Kingdom changed monarchs; Queen Elizabeth celebrated 70 years on the throne in 2022. Many don't really remember, or even know, the details of royal succession. At the very least, we're thankfully far, far removed from the days of bitter and bloody battles for the throne.

And yet there are still a lot of rules left over from earlier centuries that the British government and monarchy must still abide by. Prominent amongst them is the very clear tenet that no one who is Catholic shall ascend to the throne. And make no mistake, this is a hard, fast, intractable law that's not likely to change any time soon. It doesn't have anything to with some great, present-day hatred within England towards Catholics, although prejudices do still exist, as The Guardian outlines. It has everything to do with the glacially slow churn of political and religious change, especially in a very old country like England with a long-established monarchical tradition. Specifically, it has to do with the Act of Settlement of 1701, passed to ensure a peaceful change of hands from leader to leader, as the Royal Household explains.

The long reason, though? It's way, way longer than you might think and requires a crash course into 2,000 years of English history.

From Thor to Jesus in 1,000 years

To understand the very complex relationship between church and state in England, we've got to go back to the reason why England is Christian at all: Ancient Rome. Come 313 C.E., the Roman Emperor Constantine officially converted to Christianity, and the entire empire followed suit. The Romans made it all the way to "Britannia" — the Roman name for England and its surrounding islands — in 43 C.E., as Historic UK explains. By 122 C.E. they'd crossed England south to north, and abutted some ornery Scots in the north. They wiped their brows and said something akin to, "Geez, subduing barbarians sure is tiring," and built Hadrian's Wall to demarcate the edge of the empire. England stayed under Roman sway all the way to 410 C.E.

During this entire time, and until the famed St. Augustine arrived in 597 C.E., England underwent a slow change from paganism to Christianity, as English Heritage recounts. English tribes previously honored all of those gods that we've come to know from Norse mythology. Two tribes, the Anglos and Saxons (from modern-day Denmark and Germany, respectively), settled in England from the 5th to 6th centuries. By the reign of King Æthelstan (924 to 939 C.E.) they'd fused into one tribe — the Anglo-Saxons — under one king, via the British Library. Æthelstan was staunchly religious, and strengthened ties with the church in Rome.

Unified under one Catholic church

Sites like Great English Churches make it clear how messy things got when England underwent its religious change from the 4th to 10th century C.E.: regional differences, an array of languages, the interconnectedness of faith and politics, existing heathen influences on new beliefs, and so forth. But by the time of the Norman Conquest of 1066 C.E., when William the Conqueror came over from the European mainland and took over the English monarchy, "Christian" meant only one thing: Catholic. The Church was the most powerful unifying force of its time. It appointed the head of the Holy Roman Empire, a confederation of European states that lasted from 962 to 1806 C.E. (as World History explains), and also had deep ties with the Byzantine Empire; the eastern remnants of the Roman Empire that survived until 1453 C.E.

After William the Conqueror took over the English crown in 1066 C.E., he overhauled the state of Christianity in the land, as English Heritage explains. He replaced Anglo-Saxon bishops with his own Norman ones, and favored English saints got supplanted by new ones. Monasteries, churches, and cathedrals rose left and right over the next 150 years, and order after order of friars – Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites, and Augustinians — took root and swallowed up the Gilbertines, England's native order. England underwent a religious fervor during this period through the crusades (1096 to 1291 C.E., via History), which took a turn during the Protestant Reformation in the early 1500s.

Henry VIII, founder of Anglicanism

Here's where things get odd and even messier. By the 1500s, how could such a staunchly Catholic nation undergo a change radical enough to lead to the modern-day British crown completely outlawing the ascension of a Catholic to the throne? Quick answer: King Henry VIII, who ruled from 1509 to 1547.

Henry VIII was a highly religious person who "had no wish and no need to break with the Church," as Professor Andrew Pettegree at the University of St. Andrews told History. He had the expected array of money and power of someone in his position but lacked one thing: An heir. He married his brother Arthur's wife, Catherine, after Arthur died and he was crowned. Catherine got pregnant seven times, and only one child — Henry's daughter, Mary — survived past infancy. As Royal Museums Greenwich tells us, Henry thought he was cursed by God for marrying his brother's wife and turned his amorous attention to one of Catherine's ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn. Anne got pregnant, and Henry wanted to do something very commonplace nowadays: Get divorced and re-marry.

The pope, however, denied Henry VIII's request because of a potent political reason: Catherine's nephew, Charles V, was the Holy Roman Emperor. And so, Henry married Anne in secret, and the Church excommunicated him. Then in 1534, Henry passed the Act of Supremacy establishing him as the head of a new church: The Church of England, aka the Anglican church. Anglicanism piggybacked on the rise of Protestantism and became, technically, a Protestant denomination.

The reign of Bloody Mary

Henry VIII's move to found his own church had a tremendous economic and political impact. All the Catholic church's property and holdings in England were absorbed by the Crown and changed hands in "the greatest redistribution of property in England since the Norman Conquest in 1066," as History quotes Professor Pettegree. In a shift similar to William the Conqueror overhauling Christianity in England from 1066, so too did Henry VIII's Reformation — as it came to be called — rebrand all the churches, monasteries, cathedrals, parishes, etc., in the country to "Anglican."

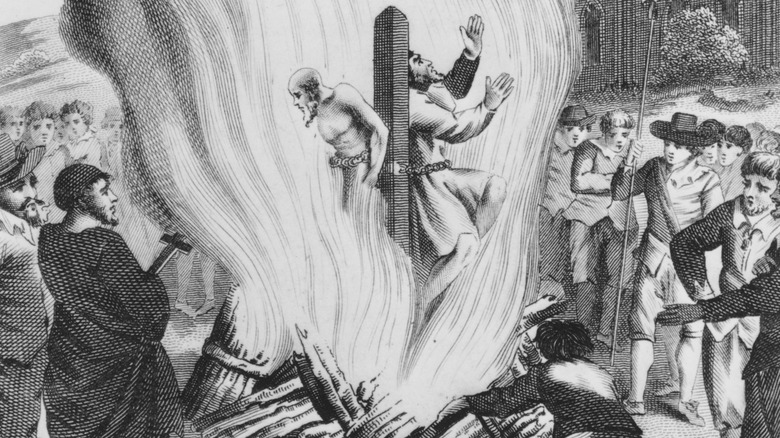

Our tale doesn't end here, however. After all of this work — irony of ironies — Henry VIII and Anne couldn't produce a male heir, anyway. Henry turned his attention to another lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour, and Anne was eventually executed on charges of adultery, conspiracy against the king, and other illicit charges (per a separate article from History). Henry and Jane did produce a male heir in 1537, Edward VI, but he died in 1553, seven years after his father's death. Then, Henry's sister Mary became queen. "Bloody Mary" began a short-lived counter-Reformation to re-Catholicize England, and burned Anglicans who refused to convert at the stake as History on the Net reports. She died in 1558.

Elizabeth I became queen in 1559, reinstated Protestantism, and set about stabilizing England, as Royal Museums Greenwich says. At this point, there was plenty of tension between Catholics and Protestants, but Catholics could still legally take the throne.

No more Catholics, ever

Less than 100 years after Elizabeth I died in 1603, England kicked off its final round of Catholicism vs. Anglican. The Glorious Revolution of 1688, as it was called, began in 1685 when King James II took the throne. James wasn't just Catholic, he was super Catholic. And because of the eternal entanglement of religion and politics, England's history of contentious religion-swapping came to a head under his reign, but in surprisingly peaceful way.

As Historic UK says, James II began his rule by appointing Catholic after Catholic to positions of power. It only took three years for many people — nobles and commoners alike — to get fed up with him. By this point, though, folks far and wide were afraid of bloodshed and civil wars. To make a long story short, the nobility took the bloodless route and pushed James out through rumors and innuendo regarding his heirs. In 1689, James fled the country and went to France. His daughter, Mary, was offered the throne on the condition that she would rule jointly with her Dutch Protestant husband, William of Orange.

England passed the Act of Settlement only twelve years later, in 1701, which sought to maintain peace and lines of succession by banishing Catholics from the throne forever. As the Royal Household continues, the act stands to this day. It took all the way to 2013, under the Succession to the Crown Act, for royals to even be allowed to marry Catholics.