Things Maestro Leaves Out About Leonard Bernstein And Felicia Montealegre's True Story

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

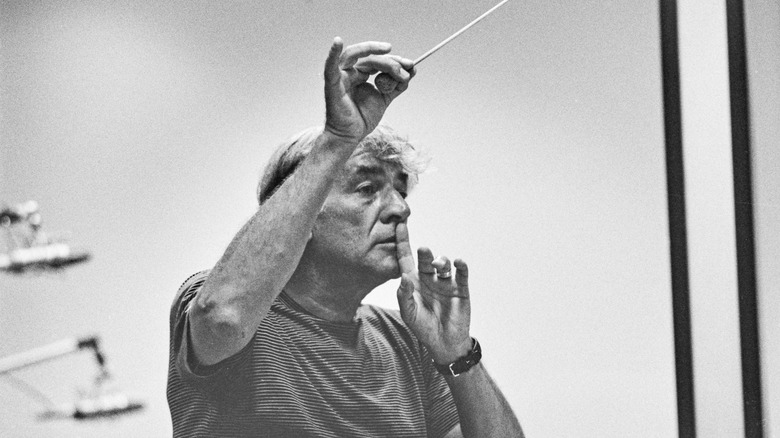

It might be assumed that "Maestro" is a traditional biopic about legendary musician, composer, and conductor Leonard Bernstein, portrayed by Bradley Cooper. However, the film is instead the story of his loving but tumultuous marriage to actress Felicia Montealegre Bernstein, portrayed by Carey Mulligan. After meeting in 1946, the two were instantly smitten with each other and would go on to share a deep bond romantically and artistically. However, Bernstein's dedication to his craft, not to mention his overt homosexuality, would cause a rift between them in their later years. The two would later reconcile after Montealegre was diagnosed with lung cancer; Bernstein put his career on hold and cared for her up until her death in 1978.

In taking a more unique approach to chronicling Bernstein's life, Cooper – in his second outing as director, co-writer, and star following "A Star is Born" in 2018 – leaves much of Bernstein's major musical and political accomplishments out of the picture. Those expecting reenactments of the creation of "West Side Story" or Bernstein's concert at the falling of the Berlin Wall will be left disappointed. However, even in the stricter context of Bernstein and Montealegre's marriage, Cooper paints broad, if not wholly inaccurate, strokes over a number of important details that help to better color their unique partnership. Here is just a taste of what "Maestro" left on the cutting room floor.

Felicia Montealegre was originally born in Costa Rica

When we are first introduced to Felicia Montealegre in "Maestro," it is quickly explained that she has arrived in the United States from Chile to become a successful actress. Many would be quick to assume that, because she came from Chile, Montealegre is Chilean. However, she was actually born in Costa Rica to a native mother, Clemencia Montealegre Carazo, and an American father, Roy Elwood Cohn.

Born Felicia María Josefa de Jesús Cohn Montealegre, she remained in Costa Rica until her father relocated their family to Santiago, Chile, so he could take a leadership position at an American mining company. Along with her two sisters, Nancy and Madeleine, Felicia was raised in a bilingual household, speaking both English and Spanish.

"Maestro" also glances over Montealegre's journey to the United States. She knew from a young age that she would immigrate to North America, hoping to become an actress. However, her parents disapproved and instead had her study under family friend and accomplished pianist Claudio Arrau (he would go on to introduce her and Leonard Bernstein, which the film instead portrays as having been done by Leonard's sister, Shirley, portrayed by Sarah Silverman). Montealegre complied to appease her parents, but she had no intentions of becoming a pianist. She would enroll in drama school shortly after arriving in the United States, and make her Broadway debut just two years afterward.

Felicia Montealegre was convinced she would marry Leonard Bernstein after seeing him perform

Bradley Cooper and Carey Mulligan first share the screen as Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre during a house party, which reenacts how the two first met in 1946. However, in reality, Felicia had known of Bernstein before this first meeting — as had most of New York City.

According to biographer Meryle Secrest's Bernstein biography, "Leonard Bernstein: A Life," a friend of Montealegre's had suggested she marry Bernstein, but the aspiring actress was far more focused on fostering her career. However, after attending a New York City Symphony Orchestra concert conducted by Bernstein, she was so impressed by him that she was determined to marry him.

This concert was mere hours before they would meet at the aforementioned party. Her piano teacher, Claudio Arrau, was a featured soloist at the concert and hosted the party at his home in Queens, New York. Arrau personally introduced the two later that night and it was love at first sight. As documented in Secrest's biography, Montealegre describes her experience meeting Bernstein as being "completely bowled over ... It's very rare that people see and meet someone with whom they feel they are destined to share a life."

Leonard Bernstein used therapy to better understand his bisexuality

One of the daunting realities looming over "Maestro" is Leonard Bernstein's sexuality. The musician had everything from casual trysts to deeply meaningful love affairs with both men and women, however, the film only lightly engages with the messiness behind Bernstein's affairs. In a series of letters edited by Nigel Simeone, much greater detail is excavated regarding Bernstein's struggle, including his time spent in therapy both before and after he began his relationship with Felicia Montealegre.

In an attempt to reconcile his urges, Bernstein spoke to multiple analysts and often explained his dreams to receive psychological interpretations. Bernstein's most frequent contact was psychoanalyst Marketa Morris, who interpreted from his dreams a constraining duality in his sexuality that became a pattern he couldn't escape. "In your dreams there is confusion," she describes in one letter, "you are not able to go where you have to go ... You are seeing Felicia and the day she leaves you have to see a boy ... You can't give up."

Bernstein's disparate sessions of analysis would not satisfy him, and only send him into further depression. "I can't kid myself any more," he explains in another letter, "into thinking that I have a closeness with someone when it is all really wishful thinking ... I find that I'm not at all interested in seeing anybody ... I used to run and see anybody at the drop of a hat. This all makes the trouble harder ... I still hate being alone, and yet don't want anyone in particular."

Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre briefly called off their initial engagement

Though briefly alluded to in the first half and very quickly mentioned in the second, "Maestro" does little to inform audiences of a crucial five-year period between Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre's engagement, and their eventual marriage. Not too long after they were initially engaged in late 1946, Bernstein consistently delayed marrying Montealegre due to a busy schedule of career developments, unforeseen health problems, and his still-prominent homosexuality. By December of 1947, an impatient Montealegre formally canceled their wedding plans, unwilling to wait for commitment.

Bernstein continued to pursue her, but Montealegre's career soon began to flourish, and she was no longer interested in playing second fiddle to Bernstein's unbridled popularity. This focus on her career led to Montealegre falling for frequent co-star Richard Hart (though he is briefly portrayed in the film by Tim Rogan, they share no scenes together as a couple).

Despite being both a married man and an occasionally violent drunk, Montealegre fell deeply in love with Hart and had moved on from Bernstein. However, Hart would suffer a heart attack from symptoms of his alcoholism in January 1951 and die shortly thereafter. As a result, Bernstein and Montealegre reunited as a couple and, by the fall of that same year, were re-engaged and formally married.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Felicia Montealegre converted to Judaism so she could marry Leonard Bernstein

If there's one glaring part of Leonard Bernstein's story that is especially missing from "Maestro," it is his strong Jewish identity. From the roots of his Orthodox upbringing to his staunch support of Israel later in life, there's no denying Bernstein's Judaism heavily influenced his work and his relationships.

"Maestro" covers his decision not to change his surname from "Bernstein" to "Burns" so that he could hide his Judaism, but an even greater concession is entirely omitted. Though Montealegre was ethnically Jewish on her father's side, the Jewish law states that a person is identified by the religion of their mother; this meant that Montealegre was considered Catholic and, by all accounts, not Jewish. In addition, Montealegre was raised Catholic and was not a practicing Jew.

This naturally concerned Bernstein's parents, who wished for him to marry a Jewish woman and raise his children Jewish. His father, while still giving them his blessing, requested Montealegre convert to Judaism, which she did before the wedding (despite this upsetting her own parents). Despite this, Montealegre never fully embraced Bernstein's Jewish tradition. She raised their three children with a hybrid of both Jewish and secular holidays. At the end of her life, Montealegre even requested there be no rabbi at her burial (Lenny would later involve a rabbi anyway). However, Bernstein remained very involved in the Jewish world of classical music and maintained his Jewish identity throughout his entire life.

Leonard Bernstein had affairs with both men and women

"Maestro" is largely concerned with Leonard Bernstein's homosexual affairs, as these caused the greater stir. Not only was being an openly gay public figure controversial when Bernstein was first garnering popularity, but it also often put Bernstein at odds with his traditional Jewish upbringing. However, according to Bernstein's biographer Humphrey Burton, Bernstein often had affairs with men and women both before and during his marriage to Felicia Montealegre.

They included Rhoda Saletan, his dentist's daughter, and Ellen Adler, the daughter of actress Stella Adler. That said, history more distinctly recalls his close male friends, including clarinetist David Oppenheim, classical composer Aaron Copland, and later music director Tom Cothran. Montealegre knew of Bernstein's homosexual affairs before marrying him and initially accepted him for who he was. She was convinced that, because he loved both men and women, Bernstein could discreetly give into his physical desire for men without sacrificing a marriage based on a deeper connection.

In a now-famous letter unearthed from the Bernstein archives, Montealegre revealed her progressive mindset on the topic: "You are a homosexual and may never change ... if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depend on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? ... let's try and see what happens if you are free to do as you like, but without guilt and confession, please!" These words would naturally backfire, as his relationships with men would almost destroy their marriage toward the end of Montealegre's life.

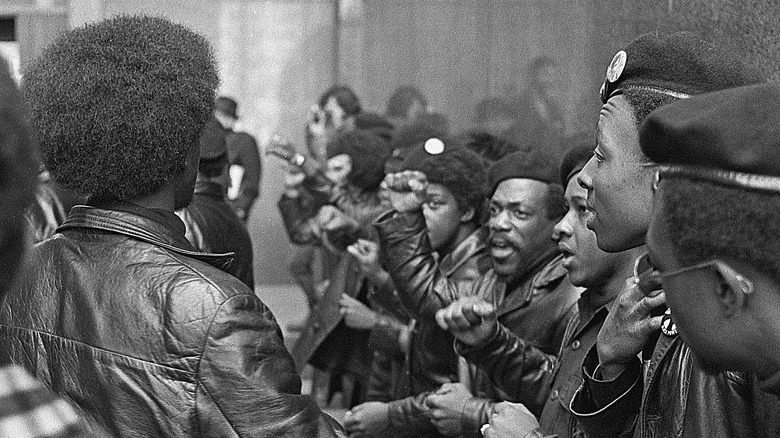

Lenny and Felicia hosted an infamous dinner with the Black Panthers

One wouldn't know it after watching "Maestro," but Felicia Montealegre was involved in many civil rights movements throughout the 1960s. She even co-founded the women's division of the ACLU's New York office. The majority of her efforts gave her a reputation as an openhearted humanitarian. However, one now infamous incident caused such a press frenzy that it put a stain on Leonard Bernstein's seemingly spotless reputation.

In 1969, 21 members of the Black Panther Party, a radical Black civil rights group, were indicted for conspiracy after it was discovered they had conspired to kill police officers and bomb multiple locations in New York City. However, they were not given a fair trial, and the bail was set so high that they were forced to remain in solitary confinement. After hearing this, Montealegre set up a dinner to raise funds in support of both the Panthers and their families.

The dinner was seemingly a success, having raised over $10,000 for the cause. However, the press spun the event as Bernstein showing naive support for the Black Panthers, who were not only openly anti-Zionist but often deemed as domestic terrorists. Several major publications wrote damning articles about the event, leading crowds to picket at Bernstein's events. Though Montealegre and Bernstein endured the public shaming, which surely caused a rift in their relationship, it is nowhere to be found in the final film.

Both Jamie and Alexander Bernstein learned their father was bisexual through gossip

One of the film's most heartbreaking moments is when Leonard Bernstein confronts his daughter, Jamie Bernstein (portrayed by Maya Hawke), about rumors she has heard about his homosexuality. Lenny denies the rumors, claiming it stems from people's pitiful jealousy. Jamie is relieved to hear that her father's sexuality isn't in question, but Lenny's eyes tell you there is far more to the story, which there is.

Jamie Bernstein's memoir, "Famous Father Girl," recounts this moment – the film recreates it with relative accuracy – but her feelings on the situation, in hindsight, are more complex. During a summer working at Tanglewood, the summer home for the Boston Symphony Orchestra in which her father was a legendary figure, the young Bernstein heard gossip about her father's homosexual affairs and was stunned. She wrote her father a passionately disillusioned letter, hoping she could speak to him about these rumors. Montealegre wrote back suggesting she come home, during which Leonard quelled Jamie's fears.

However, the film doesn't include what happened afterward. Upon Jamie's return to Tanglewood, she went to find her brother, Alexander Bernstein, who had also been working there at the time. The two smoked a joint together and discussed what happened. It turns out that Alex had also heard about the rumors while at Tanglewood and sported a similar disillusionment. Jamie writes, "Alexander and I stared helplessly at each other and were silent. But at least we had aired the subject."

Leonard Bernstein ran off with his lover, Tom Cothran, for multiple weeks at a time

In the second half of "Maestro," a major new character is introduced: Tom, or Tommy, Cothran, portrayed by Gideon Glick, the music director of a local radio station. Though he plays a pivotal role in the film's ongoing story, the extent of his relationship with Leonard Bernstein is left on the periphery. The two became entangled in a multi-year affair that would almost tear Bernstein's marriage to Felicia Montealegre apart.

Bernstein first met Cothran while at a party in San Francisco (the film depicts them meeting in Bernstein's home) and immediately fell in love with him. Bernstein valued Cothran's musical aptitude and affection so dearly that he made Cothran his right-hand man and a close friend to his family. Montealegre, who well knew Bernstein was openly having an affair with Cothran, began to feel bitter about his presence and quietly separated from Bernstein after it became too much for her to bear.

"Maestro" depicts this separation, but not how long it went on. It began with a six-week excursion to California, followed by weeks of performances across Europe. They vacationed for multiple weeks across Barbados, Palm Springs, and even Morocco. However, there was trouble in paradise; between getaways, Bernstein and Cothran would return to New York and brace hostility from Montealegre as well as Bernstein's children and friends. This naturally caused resentment between the two. Bernstein officially called off the relationship and reconciled with Montealegre in 1976, days before she was diagnosed with lung cancer.

Lenny was buried next to Felicia after he died of a heart attack in 1990

The final stretch of "Maestro" depicts Felicia Montealegre's battle with inoperable lung cancer between 1976 and 1978. Leonard Bernstein put many of his artistic responsibilities on hold so that he could take care of her in the final years of her life, reforging the strong bond they once shared toward the beginning of their marriage. She would die in his arms in 1978, after which Bernstein would never emotionally recover.

The film shows very little beyond Montealegre's death. Audiences get a brief look at Bernstein's later years, during which he continued working at Tanglewood and lived a far more open life as a queer man. What audiences don't see is Bernstein's heart attack in 1990, as a result of his emphysema. Both Montealegre and Bernstein were habitual smokers and died due to similar complications. Bernstein was buried next to Montealegre in Brooklyn's Green Wood cemetery, symbolizing their still-deep connection, despite years of turmoil. Bernstein was also buried with, amongst other things, a baton and a copy of Gustav Mahler's 5th Symphony, signifying Bernstein's deep love for Mahler's work.

Lenny and Felicia's three children continue to maintain their parents' legacy

Little is made of Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre's children in "Maestro." Jamie Bernstein is a minor supporting character during the film's second half, and her other two children, Alexander and Nina, portrayed by Sam Nivola and Alexa Swinton, respectively, have little screen time or dialogue. Despite this, they each remain outspoken members of the Bernstein clan, and have each done work to maintain and preserve their family's legacy. Bradley Cooper heavily consulted all three throughout the filmmaking process, which likely contributed to the film's accuracy.

The oldest, Jamie, went on to become a concert narrator, a broadcaster, and even a filmmaker in her own right. Her memoir, "Famous Father Girl," gave longtime fans new insights into her relationship with her father and the many nuances behind their family's struggles. Alexander would receive Bachelor's and Master's degrees in education and teach for five years, before taking leadership positions at The Leonard Bernstein Office, an organization that "sustains and strengthens Leonard Bernstein's legacy by inspiring global engagement with his work," as described in their website.

Nina currently serves as a nutrition educator for impoverished communities, however, she too bolstered her father's legacy by helping the Library of Congress digitize his archives during the internet's infancy. Needless to say, both Lenny and Felicia are proudly represented to this day.