Lord Of The Rings Details Inspired By J.R.R. Tolkien's Service In WWI

There's a decent chance you're familiar with the famous writers connected with World War I — good old Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, E. E. Cummings, and the whole band of Lost Generation writers. That classification has been around for a long while, but have you ever considered adding J.R.R. Tolkien to their ranks? (Well, the ranks of World War I writers; the Lost Generation was an American movement, if you want to be technical, and Tolkien was a Brit.)

Yes, the author of "The Lord of the Rings" and "The Hobbit" can be considered a World War I writer. Plenty of discussions have been had regarding Tolkien's influences and just how much of his World War I service actually seeped into his books. Mind, Tolkien himself had quite a bit to say on the topic: "It is neither allegorical nor topical ... I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence" (via Mythlore). That's from the foreword to "The Lord of the Rings," which does shut down that argument to a degree.

That said, it's pretty hard to deny some similarities between "The Lord of the Rings" and World War I, and despite Tolkien refuting the claims his story was an explicit allegory, he has admitted to some influences gleaned from his wartime service. The Great War may never have happened in Middle Earth, but it certainly seemed to shape it.

The importance of literature in Middle Earth

If you've read "The Lord of the Rings," it's hard to forget just how many songs the characters sing, especially in the early part of the story. This might seem silly, especially in the context of a huge war between good and evil, but it actually comes from very real circumstances around the time of World War I.

In the late 19th century, there was a push in Britain toward greater public education. The Education Act passed in the 1870s led to the construction of state-funded schools all around the country. Young people could finally be guaranteed an education, and literacy rates skyrocketed to over 95% by the turn of the 20th century. By World War I, many British soldiers were well versed in literature, often making reference to novels in their letters home, comparing themselves to their favorite fictional heroes. The war even gave rise to a literary genre known as "trench poetry."

Literature plays a similar role in "The Lord of the Rings." The citizens of Minas Tirith sing about old myths as a way to get through dark days of war during "The Return of the King." And in "The Two Towers," Sam directly compares himself and Frodo to the heroes in his favorite tales: "I used to think that [adventures] were things the wonderful folk of the stories went out and looked for ... But that's not the way of it with the tales that really mattered ... I wonder what sort of a tale we've fallen into?"

Small moments of respite

While the main plot driving "The Lord of the Rings" is a war between the forces of good and evil, you really don't have to look hard to find moments of respite. Of course, there are the big examples of this — entire locations that are literal oases right when the characters need them most. The hobbits and Aragorn arriving in Rivendell, right after the encounter at Weathertop. Or the Fellowship finding their way to Lothlorien after the (apparent) death of Gandalf. But there are the smaller, more intimate beats that shine as well, in which characters find moments of peace. After being captured by orcs, Merry and Pippin take a bite of lembas bread and feel themselves whisked back to happier times, nearly forgetting the battle raging around them. And even while inside Mordor, Sam can glance toward the sky and feel hope as he finds a star shining through the clouds.

World War I was oddly similar in certain ways (well, minus the magic bread and orcs). There were famously peaceful respites in the midst of the war: the Christmas Truce of 1914, for example, in which British and German soldiers just stopped fighting, instead meeting in No Man's Land to chat, play soccer, and trade drinks. But the smaller moments likely pulled from more common experiences. C.S. Lewis commented on this in his own work "A Reader's Companion to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings," making note of "such heaven-sent windfalls as a cache of choice tobacco."

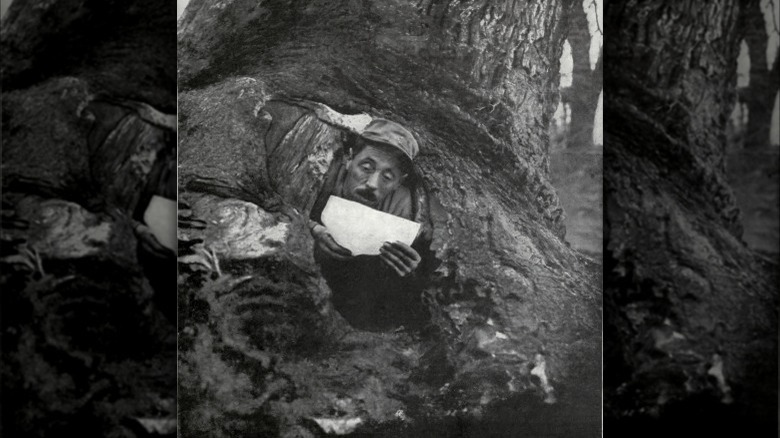

The imagery of the Dead Marshes

Most of the time, J.R.R. Tolkien was pretty loath to admit to any part of "The Lord of the Rings" pulling from his experiences in World War I. But that wasn't always true, and there are a few things that he did explicitly state were at least somewhat influenced by the war. In his own words, written in a letter from 1960: "The Dead Marshes and the Morannon owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme" (via "The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien").

For reference, the Battle of the Somme was a 141-day-long battle of attrition; with a total casualty count of over 1 million, it wasn't just one of the bloodiest battles of World War I, but one of the bloodiest battles ever fought. It was also accompanied by some particularly disturbing sights, such as corpses sinking slowly into the mud as the battle dragged on. Or, especially relevant in this case, there's Siegfried Sassoon's account from "Memoirs of an Infantry Officer": "Floating on the surface of the flooded trench was the mask of a human face which had detached itself from the skull."

It's certainly an eerie image, and one that's similar to the sights of the Dead Marshes. Sam falls into the water, exclaiming, "There are dead things, dead faces in the water" (via Tolkien's "The Two Towers"). Frodo notes their pale, sad faces, and Gollum adds further context, explaining that these people died in battle years ago, only for their bodies to be swallowed up by the marsh.

Frodo, Sam, and shell shock

Nowadays, PTSD is a recognized condition that afflicts plenty of soldiers returning home from war, but the same couldn't be said in the early 20th century. World War I was actually the first time that this kind of trauma was ever officially noted, and it went by a different name: shell shock. Many accounts have survived talking about how the trauma affected people long after the war's end. British veteran Edwin Bigwood noted, "They never really recovered in mind," and Bertram Steward said, "One of my friends ... was accustomed to shut himself up in his home or in his garden and he wouldn't come out at all" (via IWM). In other cases, after soldiers returned home, they just couldn't find ways to talk about their experiences; it was too much to parse.

"The Lord of the Rings" illustrates both of those cases perfectly, with Frodo being the primary example. Plenty of Frodo's actions immediately after the destruction of the One Ring align with our modern-day understanding of PTSD, and memories of the journey haunt him for years, even after he's returned home. He withdraws from the rest of the Shire and eventually has to leave Middle Earth entirely for the Undying Lands, unable to return to the life he used to know. Meanwhile, Frodo sees that Sam can heal, but he wasn't free of trauma. Specifically, he found he couldn't explain anything that happened to Rose, because the entire experience was too horrible and complicated to put easily into words.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

The hobbits' return to the Shire

If you only know the movie version of "The Lord of the Rings," then here's a chapter that's pretty notably left out. "The Scouring of the Shire" features the hobbits returning home, only to find it entirely changed. Many of their friends are imprisoned, and Saruman is at the head of this imposed totalitarian regime. They defeat him, of course, but an article from Mythlore posits that the hobbits finding their home so different is a direct comparison to J.R.R. Tolkien himself, who returned from war to an England he didn't recognize.

There's the effects of loss, of course, but there's another interesting facet to this. Tolkien was notably anti-modernist, and "The Lord of the Rings" exemplifies those beliefs very explicitly. The evil forces of Saruman and Sauron are heavily industrialized, often tearing down or twisting nature wherever they go; in contrast, good-aligned people and locations have plenty of natural influences. (Lothlorien and Rivendell are built into natural environments, but even the city of Minas Tirith has its gardens.)

In real history, World War I actually changed the face of London; quiet and relatively empty districts in the western part of the city became the home of munitions factories, and even more industries began to move into the area immediately after the war ended. Tolkien returned to find once-empty sectors of England filling with factories, just as the hobbits were literally met with a stone and metal gate built at the behest of Saruman, one of the main industrial forces in Middle Earth.

The prevalence of humor

You'd think that when facing down the threat of an evil lord, his huge, floating eye, and the corrupting influence of the One Ring, there wouldn't be a lot of space for humor. In that same vein, you could easily assume that the middle of the trenches, constantly threatened by gunfire, would be the last place you'd find comedy. But in reality, the truth is exactly the opposite in both cases.

Many soldiers used dark humor to make life in the World War I trenches a little more bearable. British soldiers even started up their own fake newspapers. They were filled with articles, ads, sports and entertainment sections, and even works of fiction and poetry. Nearly every piece was chock-full of darkly humorous takes on the war, whether that be advertising the latest in trench fashion, describing the battles as if they were a popular sporting match, or likening attacks to the latest movie. (Not to mention a parody of Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, instead named "Herlock Sholmes.")

The characters of "The Lord of the Rings" do much the same thing (albeit, not by riffing on popular fictional detectives). Upon being captured by the orcs in "The Two Towers," Merry asks Pippin where they could get bed and breakfast, calling the entire thing a "little expedition." And there are Legolas and Gimli, who quite literally turn a battle into a sporting competition with each other. (Who can forget the two of them yelling out numbers as they slaughter orcs in the movie?)

Messy systems of alliances

If there's one thing to be said about the causes of World War I, it's that they were complex, with many different factors all happening to erupt at the same time. One of those factors was a twisted system of alliances that had sprung up in the decades preceding the actual war, with various countries basically picking sides long before any fighting broke out. So when conflict did arise due to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, both Serbia and Austria-Hungary looked to their respective allies for support. Presumably, those alliances were invoked to try and prevent war, but instead, it pulled many nations into a conflict that could have, hypothetically, remained a local problem — something for Serbia and Austria-Hungary to sort out on their own.

The conflict in "The Lord of the Rings" can actually be described in almost the exact same terms. When Sauron began to build up his forces in Mordor, that immediately posed a threat to Gondor, making them the equivalents of Austria-Hungary and Serbia in this situation. Any ensuing war could have, technically, remained between those two nations, but both called on other forces. Sauron allied with Saruman and his forces in Isengard, leading Gondor to reach out to Rohan and the Rangers of the North for aid. Suddenly, all of these nations were involved in a fantasy version of a world war.

Sam Gamgee and the honorable British soldier

Given J.R.R. Tolkien's stance on allegory, it's really not that surprising that he gave very few examples of World War I inspiring anything in "The Lord of the Rings." But there was one aspect of the story that he openly admitted was influenced by the war: the character of Sam Gamgee. In a 1956 letter (via author John Garth's website), he wrote, "My 'Samwise' is indeed ... largely a reflexion of the English soldier ... the memory of the privates and my batmen that I knew in the 1914 War, and recognized as so far superior to myself."

There's even more nuance here, though. "Batmen" isn't a reference to a superhero, but rather a soldier assigned to cook, clean, and generally assist an officer, usually coming from a lower social class than said officer. Already sounds a lot like Sam, right? But more than that, as officers were usually given their titles due to class, they typically weren't terribly experienced or particularly capable; in practice, they usually ended up relying pretty heavily on their batmen to help them out. C.S. Lewis made this point succinctly by praising his own batman, writing, "I was a futile officer (they gave commissions too easily then), a puppet moved about by him, and he turned this ridiculous and painful relation into something beautiful" (via "Surprised by Joy").

And when it comes to "The Lord of the Rings," it's pretty hard to ignore just how much Frodo depends on Sam — a pretty direct mapping of the officer and batman dynamic.

The realities of war

In a lot of stories, it's easy to hope for happy endings, especially at the end of a hard-won war. Good triumphs over evil, and the heroes finally have the chance to celebrate. Right?

But neither "The Lord of the Rings" nor World War I itself had any of that for the normal people who were forced to fight. Not the soldiers on the front line, or many of the main characters in the novel. In essence, many of J.R.R. Tolkien's characters pull their qualities from the people he served with, particularly the resilience to just keep going, to see the war through to its inevitable end. There was incredible courage to keep fighting, but also a kind of stoicism, a refusal to give in to anger. In short, the soldiers in the trenches were admirable, and the characters of Middle Earth prove themselves admirable in the exact same way.

None of it was pretty, though, and those same honorable soldiers rarely saw the glorious side of military victories. All they could really do was wait for the next battle, stewing in the futility and fear. It's an experience communicated through Merry and Pippin in the aftermath of the Battle of Pelennor Fields; the men of Gondor and Rohan are singing and celebrating their valor, but the reader saw the fighting through the eyes of the hobbits, who had a front seat for battlefield horrors. They feel no glory in that, in much the same way as World War I soldiers.

The steadfast commitment to fantasy

There's probably a reason most people don't associate "The Lord of the Rings" with World War I. On one hand, it's fantasy, but it's also fundamentally different from its contemporaries. Most writers post-World War I leaned into the dark, realistic, and ironic, preferring straightforward, simple language. J.R.R. Tolkien, in contrast, created a story that spotlighted heroism and courage, told through poetic language.

Tolkien's commitment to his unique voice — and to the fantasy genre in general — might be a direct result of the war. There are his own words on the topic, as he explained that "a real taste for fairy-stories was ... quickened to full life by war" (via Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories"). Scholars have delved even further into this idea. In "Tolkien's Great War," Hugh Brogan questioned how Tolkien could hang onto his romanticism despite the war; his conclusion was that it had to be a choice, a "deliberate defiance of modern history" (via Mythlore).

John Garth added to that in "Tolkien and the Great War," explaining that such a defiance only made sense. One of the strange effects of World War I was a vilification of the arts, romanticism, and linguistics (one branch of it, at least) — essentially all of the things that made up the basis of Tolkien's creative inspiration. That's reason enough to be upset and fight back, but given that C.S. Lewis once claimed, "No one ever influenced Tolkien. You might as well try to influence a bandersnatch," it almost seems like a foregone conclusion that he'd stick to his style.