Loretta Lynn's Tragic Real Life Story

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

When people wax nostalgic about the golden age of country music, they inevitably get around to talking about Loretta Lynn, the self-described coal miner's daughter from Butcher Holler, Kentucky. In her roughly seven decades of songwriting and singing, Lynn racked up 16 No. 1 country hits, including "Don't Come Home A-Drinkin' (With Lovin' on Your Mind)," "Fist City," and "Feelins'," helping change country music from a male-dominated genre to one that welcomes and embraces women's voices.

Her songs have spoken to people from all walks of life, probably because every song she's written has come in large part from her own experience. Many women have seen Lynn as a kindred spirit, a refreshingly candid ally in a world that often seems to favor men, especially those of the hard-drinkin,' hard-livin' variety. She also found a loyal audience in both rural and urban America, where people were itching for her unique take on hardship and triumph.

You might think that fame, not to mention the money and adoration that came with it, would have brought Lynn happiness, but what many casual country fans don't know is that her life was far from perfect. In fact, it was marred by loneliness, tragedy, and loss, but not being one to waste time feeling sorry for herself, she worked hard to put all that heartache right back into her art.

Loretta Lynn was dirt poor but proud of it

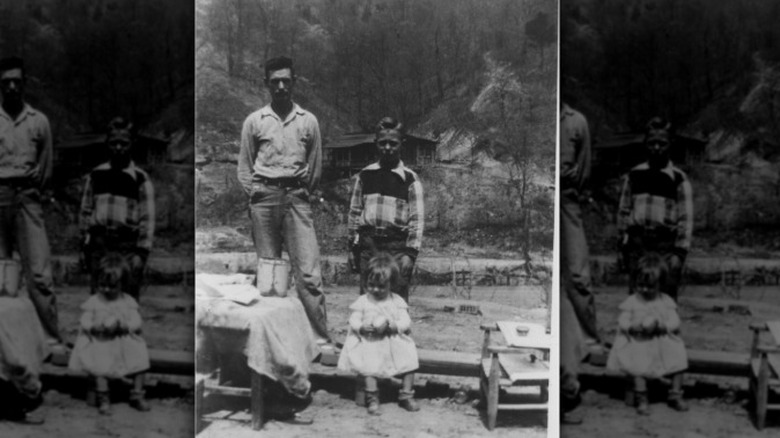

Loretta Lynn wasn't shy about what it was like to grow up the impoverished daughter of a coal miner in Butcher Holler, Kentucky. The second of eight children born to Ted and Clara Webb (pictured above; her father, brother Herman, and sister Peggy Sue), Lynn wore old flour sacks to church and school and often went barefoot. Going to bed hungry was normal; going without was simply a way of life. Lynn's early childhood years coincided with the Great Depression, when family life for many was tough, and many were in need of clothing, food, and stable shelter.

The Webbs lived in a one-room home with no electricity, running water, or indoor toilet. Clara Webb decorated the walls of the house with pages she tore from magazines. That's where Clara got Lynn's first name: She thought Loretta Young, the actress known for the film "The Farmer's Daughter," was especially beautiful and kept a photo of her over her daughter's crib.

There wasn't much to do in Butcher Holler except socialize with the neighboring families, keep the house running and clean, watch babies, and go to church. What the Lynn family's lifestyle lacked in excitement and worldly wealth, though, it more than made up for in love, and, in her best-selling autobiography "Coal Miner's Daughter," Lynn claimed that being poor made her strong, self-sufficient, and capable of fighting life's many battles on her own.

Loretta Lynn was Daddy's little girl

Growing up, Loretta Lynn worshiped her tender, coal miner father, Ted Webb. Webb loved his children unconditionally — incidentally, Lynn's sister, Crystal Gale, is also a country music legend — and Lynn's confidence in his affection and love helped her through many a difficult time. In "Coal Miner's Daughter," she wrote: "I feel like Daddy's been the most important person in my life. ... I had almost fourteen years of Daddy giving me love and security, the way a daddy should. ... Daddy is the main reason I always had respect for myself when times got tough between me and Doolittle. I always knew my daddy loved me."

Lynn's husband, Oliver "Doolittle" Lynn, made two promises to Ted when he married Loretta against her father's wishes. First, he said he would never physically harm her. Second, he promised not to take her away from her family. He quickly broke both promises: On their wedding night, he beat Loretta for jokingly calling him a whore, and then he dragged her all the way to Washington state to work in the logging camps.

Loretta was in Washington when Ted Webb died of a stroke at 51. The loss was almost impossible to bear, and she was overwhelmed with guilt and grief. Her Christian faith, though, helped her survive that loss, and it would get her through many more losses in the years to come.

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

As a child bride, Loretta Lynn learned the hard way

Loretta Webb met Oliver "Mooney" Lynn at a pie auction in Butcher Holler. The auction was intended to raise money for the local school, but it was also by way of a matchmaking activity. Mooney, straight from the Army and smitten with Loretta's fresh-faced, brunette beauty, bid on her pie and walked her home. Loretta fell hard and fast for Mooney, a charmer with a flair for the romantic who also had a reputation for being both a drinker and a womanizer.

Four months later and in direct conflict with her loving parents' wishes, Loretta agreed to marry Mooney. She was just 15 years old, and Mooney was 21. According to Loretta Lynn's book "Coal Miner's Daughter," she was only 13 when Mooney carried her across the proverbial threshold, but journalists accessed Lynn's birth certificate and corrected the record in 2012. Regardless, she was obviously too young to know what lay in store for her: heartbreak, financial struggles, and six kids.

The first of those children, Betty Sue, came in 1948, after the young couple had moved to Washington. Mooney, who had left Loretta for another woman when she got pregnant, came back to his wife just before the birth.

Lynn's experiences of motherhood inspired one of her biggest hits

Loretta Lynn had four children by the time she reached her mid-20s. She would go on to have two more (not to mention three miscarriages) and to write a hit song in homage to the birth control pill, which includes lines like, "This old maternity dress I've got is goin' in the garbage/The clothes I'm wearin' from now on won't take up so much yardage." "The Pill," Lynn's instant feminist anthem, was banned by a host of radio stations and denounced by several Christian leaders as sacrilegious, but attempts at censoring the tune only made it more popular.

Lynn admitted in interviews that she would have loved having access to the pill as a young woman. In fact, she said, she would have eaten the pills like popcorn, but in her memoir "Coal Miner's Daughter," she claimed to have grown up largely ignorant of reproductive matters. "I never knew where babies came from until it happened to me," she wrote.

Teenage motherhood was difficult for her; it wore her down. And she didn't get much help from her husband, who, when Lynn took to the road to tour, hired a nanny to do the hard work.

Loretta Lynn was married to a man that tormented her

Loretta Lynn's husband, Oliver, whose nicknames were "Mooney" (for his favorite drink, moonshine) and "Doo" (as in "Doolittle," a nickname whose origins were unclear), often made Lynn's life a torment. He left her when she was pregnant with their first child. He was AWOL when she gave birth to their son, Jack Benny. He even slept with her brother's wife. It is perhaps one of country music's most bittersweet stories that Lynn's first No. 1 hit was 1967's "Don't Come Home A-Drinkin' (With Lovin' on Your Mind)," an obvious nod to Mooney's dissolute habits.

Mooney disappeared for two weeks early in Lynn's life as a mother, and she and her children survived on dandelions and game she shot in her own backyard. Despite the many challenges of their life together and Mooney's innumerable failings, Lynn was devoted to her husband to the last (he died of heart failure in 1996), crediting him with laying the foundations of her career.

It was Mooney, after all, who convinced her that she had talents as a singer and songwriter. He also bought her first guitar, a $17 Harmony acoustic from Sears. She used that guitar to write "Honky Tonk Woman," the song that rescued her from poverty and obscurity and, in 1960, landed her on the Grand Ole Opry stage.

Lynn's son Jack Benny died in a tragic accident

In 1984, when Loretta Lynn's favorite child, Jack Benny, was 34 years old, he took his horse out on the family ranch in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee, and drowned while trying to ford the notoriously dangerous Duck River. Authorities say he most likely struck his head on a rock during the crossing. A search party found Jack Benny's horse under a bluff at the river's edge and the young man's lifeless body in the water.

Lynn, then 49, was in Illinois at the time of the accident and had checked herself into a hospital for exhaustion, as she had been found unconscious in the back of her tour bus. Her husband broke the news to her.

By then, Lynn had already suffered more than her fair share of heartbreak and strife. Losing Jack Benny, though, introduced her to a new world of grief and pain. In many ways, Jack Benny was like his father — in love with liquor and allergic to hard work. He'd only recently started paying more mind to his wife and children. But those flaws didn't make him any less precious to his doting mother, who, convinced that someone actually tried to deliberately hurt Jack Benny that fateful day, collapsed at his funeral and had to be taken back to the hospital afterward to heal and recover. Mooney, too, was devastated by his son's death, and the family was never the same.

Lynn outlived many of her loved ones

Loretta Lynn lived through almost unimaginable loss. In 1963, Lynn said goodbye to her friend and mentor, Patsy Cline, who died in a plane crash. Her favorite child, Jack Benny, died in 1984, having struck his head on a rock while attempting to cross a river on his horse. In 1996, Lynn's husband, Mooney, died of congestive heart failure after four years of trying to treat the disease and a veritable lifetime of causing trouble.

In 2013, her daughter, Betty Sue, died from emphysema. Three years later, Jack Benny's oldest son, Jeffrey, died unexpectedly on the family ranch in Tennessee. And that's not even counting the deaths of her frequent collaborator, Conway Twitty, at age 59, and her beloved manager, Owen Bradley, who died in 1998 of a respiratory ailment.

Some might say that Lynn's career as a country music artist was aided by these tragic losses, given the country genre's reputation for songs about crying in one's beer over cheating spouses, dead parents, and missed opportunities. It's true that Lynn's songs were inspired by her own life and experience, but she often told her daughters that if she could have picked between being a famous musician always away from home when tragedy hit and being a nobody who had more time with her family and friends — even if that meant confronting loss firsthand — she would have certainly picked the latter.

Loretta Lynn often pushed herself to exhaustion

In the 1980 film "Coal Miner's Daughter," a rags-to-riches tale adapted from Loretta Lynn's memoir of the same name, the character of Lynn, played by Sissy Spacek, has a serious mental break on stage. The moment is a condensation of a number of episodes of exhaustion and mental health issues that Lynn experienced during her years of relentless touring, and the scene was not far off the truth.

In the early to mid-1980s, Lynn was performing as often as twice a night — sometimes until the early hours — for 10 months a year, and her extreme work ethic dated back to her earliest days of singing success some two decades prior. Returning home was little respite, as the family ranch she worked tirelessly to pay for was waiting with a nerve-wracking amount to do, which her husband was reportedly too distracted to take care of fully. Lynn's husband of 48 years, Oliver "Mooney" Lynn, was an alcoholic womanizer and, to a large extent, a deadbeat. While Lynn spent months on the road, touring and making money to support their large family, he drank, slept around, and spent Lynn's hard-earned dollars on land they could neither afford nor take care of.

The stress eventually got to Lynn more than once, who at one point turned to sleeping pills, albeit with little success, and she was hospitalized more than once for exhaustion-related medical issues such as bleeding ulcers, high blood pressure, and migraines.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Loretta Lynn had excruciating migraines for much of her life

During her performances, Loretta Lynn would sometimes need to leave for extended breaks while her band members played on. This and other sporadically unusual onstage behaviour, including passing out on stage, led to rumours of intoxication, but the reality was that Lynn had a lifelong experience of dealing with serious and extremely painful migraines.

In her memoir "Coal Miner's Daughter," Lynn revealed that she had her first migraine at 17, and that her father was also prone to such painful episodes that they would reduce him to tears. For Lynn, the migraines would drive her to cut or pull out her hair, and on one occasion, the pain of a migraine even brought Lynn close to death by suicide. The effectiveness of any medical treatment she was given was spotty, with water pills (to prevent brain swelling) and anti-nausea injections — among other treatments — giving only brief respite.

Loretta Lynn's songs have been repeatedly banned

Loretta Lynn wrote 14 songs that were, to varying degrees, banned from the radio because of their sensitive and controversial subject matter. The first song to offend the delicate feelings of mid-century American DJs was "Fist City," in which Lynn warns another woman that if she keeps pursuing her man, the other woman will get a right hook in the kisser. The tune, incidentally, was inspired by real-life events. While out on tour, Lynn learned her husband, Doo, was keeping company with a certain woman who had come to town just to pursue him. Lyunn, furious, quickly traveled home to confront Doo, composing the song in her head as she drove.

"The Pill," her love letter to contraception and the freedom it gives the women who take it, also caused a stir in the country music community. So did "Rated X" (her exploration of divorce), and "Don't Come Home A-Drinkin' (With Lovin' on Your Mind)" (her repudiation of drunk sex), "One's on the Way" (arguably her most unapologetically feminist song to date), and "Wings Upon Your Horns" (a look at losing one's virginity through the lens of Christianity).

Lynn had always written songs about real life, real problems, and authentic situations, and that made a number of people uncomfortable. "Sometimes," she told The Wall Street Journal, "I write songs in a way where they can't play 'em."

Was Loretta Lynn the other woman?

As if Loretta Lynn didn't have enough to manage with her husband drinking away some of her profits and cheating on her with at least three women (including her children's bus driver), her own powerful and often steamy duets with fellow country music legend Conway Twitty led some fans to blame her for the breakup of Twitty's first marriage.

Lynn and Conway Twitty, good friends and frequent collaborators, put out, much to Doo's hypocritical consternation, the No. 1 hit "After the Fire is Gone" in 1971 and the album "Lead Me On" in 1972. The passion in the songs Lynn and Twitty made together had a number of people (not just Doo) suspecting that their enthusiasm for each other couldn't possibly be limited to the studio.

Lynn always insisted that their relationship was purely platonic, though, and that Doo loved Twitty as much as she did. Also, Twitty remarried Temple "Mickey" Medley, the wife he divorced in 1970, and remained married to her until 1984, so Lynn's rumored stint as the other woman was short-lived.

Loretta Lynn fought against rumors about her death

Over the course of her long life, Loretta Lynn fought many battles. In her later years, those were often with the tabloids, whose stable of sleazy writers kept insisting she was either dead, dying, or being thrown in a home by her uncaring family.

In response to one such rumor, Lynn wrote on her Facebook page that she'd had enough of it: "Well, through the years they've said I'm broke, homeless, cheating, drinking, gone crazy, terminally ill and even dead! Poor things can't ever get it right ... I'm about an inch from taking 'em to Fist City!"

In reality, Lynn was still actively making music. In 2004, she collaborated with Detroit folk rocker Jack White (pictured above) to put out the acclaimed "Van Lear Rose." In 2016, she got fellow miraculously-still-living-country-star Willie Nelson to collaborate with her on a song for her new album. The heart-wrenching news of Lynn's death finally came on October 4, 2022, when she was 90 years old.

Lynn had holes drilled in her head when she was a baby

Loretta Lynn's childhood in the hollers of rural Kentucky gives new meaning to "hard scrabble." Her family was so poor that she often didn't have traditional clothes to wear. Instead, her mother fashioned skirts for her out of old flour sacks. Adding to the difficulty of Lynn's impoverished upbringing was a severe ear infection she contracted when she was 11 months old, which required doctors to drill two holes in her skull to clean out the affected areas.

The family couldn't afford to keep Loretta in the hospital overnight, so every day her mother, Clara, would walk the 10 miles to the Golden Rule Hospital (its real name) in Paintsville, Kentucky, for her daughter's treatment. Lynn still bears the scars of those long-ago holes, and that is why she's always worn her hair long. The illness also goes some way to explaining why she didn't walk until she was 4.

She performed a wild show after dental surgery

Loretta Lynn was, above all, a trouper, as evidenced by the strange history of three unlucky performances in Evansville, Indiana, in the mid-1970s. In 1975, hooligans stormed the stage and punched Conway Twitty in the face for unclear reasons, with the rest of the crowd heckling her until she sang "The Pill." In 1976, she fought through a case of the flu to keep her date with fans. And in 1977, an oral cyst had required the removal of several teeth and a powerful dose of Novocain, and helpers stood ready offstage to ice her jaw between her solo set and her duet with Conway Twitty, who had apparently forgiven the Evansville crowd.

Most people who have ever had dental surgery will recognize Lynn's continuing the show for the tough-cookie triumph it was, but dental abscesses are more dangerous than they may sound, with infection possibly spreading to the throat or into the blood to cause life-threatening sepsis. Instead of choosing the safer option of resting after oral surgery, Lynn risked her health to thrill her fans.

Her marriage was sometimes abusive

Though loving, Loretta Lynn's marriage was also volatile, with Oliver Lynn's alcoholism and abusive behaviour creating a difficult situation for his wife even as her fame grew. Loretta's comments about the issue were usually not very explicit, but she did tell interviewers that she fought back — not a healthy dynamic, but what you might expect from the singer of "Fist City." At one point, she socked her drunken husband so good that two of his teeth fell out, and Oliver stayed snaggle-toothed until she made enough money singing to replace them.

Loretta's experience allowed her to be a helpful ally when her granddaughter Tayla Lynn (pictured above), also a singer, herself faced domestic abuse from her stepfather. The elder Lynn believed Tayla and took her in, gaining custody of the girl when she was 14. Tayla's grandmother remained a support for her into adulthood, supporting her as she worked to address her addiction and build a performing career. Tayla even sings with Tre Twitty, grandson of her mother's old compadre Conway Twitty.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues or is dealing with domestic abuse, contact the relevant resources below:

-

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Advertisement -

The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

Her politics tracked those of a changing South

Over the course of her career, Dolly Parton has expertly dodged political questions, remaining one of the few public figures in American life to remain above the red-versus-blue fray. She may have decided on this course after watching her colleague Loretta Lynn refuse to keep mum, instead publicly supporting Republican candidates. Despite some kind words about FDR in her memoir "Coal Miner's Daughter," Lynn was solidly on the red team by the 1980s. When campaigning with George H.W. Bush in 1988, she assured supporters he was "country," which was presumably meant as a compliment, but did not seem to be a terribly accurate description of the upper-crust New Englander.

Lynn's fans on the left side of the aisle were even more dismayed in 2016, when she endorsed Donald Trump and sang his praises at the end of her shows, though she softened this unwelcome-for-some news with jokes about getting booed if she'd supported Hillary Clinton. Nevertheless, Lynn's choice dismayed a number of fans, even if the love many had for her never truly wavered.

Lynn died in 2022 after declining health

Through the 2010s, Loretta Lynn's health started to fail, though she continued to perform as long and as frequently as circumstances allowed. In 2011, a bout of pneumonia caused Lynn to be hospitalized, and 2012 saw Lynn push back a couple of concerts while she recovered from knee surgery. In 2016, minor injuries from a fall meant she couldn't comfortably inhale deeply enough to sing, leaving her sister Crystal Gayle to carry a planned dual show alone. The next year brought worse news, with a stroke in May requiring a stay in a rehab facility and a few more months of rest as Lynn worked to improve her balance.

In September 2017, she triumphantly reappeared to induct Alan Jackson into the Country Music Hall of Fame, requiring support to stand but charming the crowd and joining Jackson in singing "Will the Circle Be Unbroken." Another fall on New Year's Day 2018 slowed the star down further, but she was well enough in June 2019 to clap back against rumors that she was on her deathbed. And she was right: Lynn lived another three years before dying in her sleep at home on October 4, 2022, at 90 years old. Little is known about what happened to the fortune Lynn left after she died.

She's left an enduring legacy

Loretta Lynn's career lasted for over 60 years and saw her release 50 albums. She was nominated for 18 Grammy awards and won four, the last in 2019, and gathered a trophy case full of accolades like the Presidential Medal of Freedom and induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Her influence was enormous, especially for other female country musicians who now had another trailblazer to follow in the mold of Patsy Cline and Kitty Wells. In a tribute in Garden & Gun magazine, Tanya Tucker – called her friend and heroine "Retti" – wrote that she was "thanking my God above for blessing me first with her music and her guidance through the perils of the music world way before we ever met." Country music fans the world over knew Lynn through her bold and from-the-heart songwriting, which will likely endure even longer than Lynn's long life and career.