Things About The Pearl Harbor Attack That Don't Make Sense

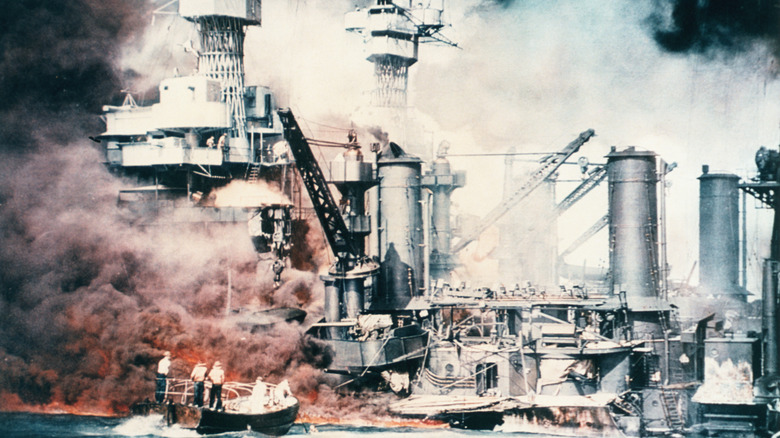

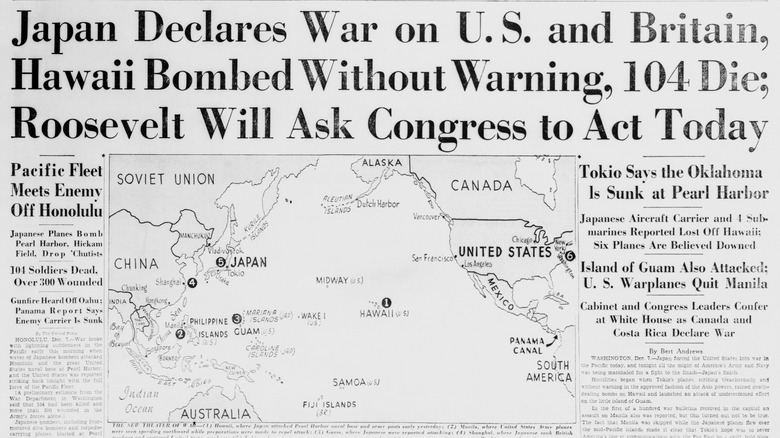

Though World War II was undeniably a complex and world-spanning conflict, for many Americans U.S. involvement comes down to one of the most important battles of the war: Pearl Harbor. On the morning of December 7, 1941, two waves of Japanese planes descended on the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor, on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. After it was all done, five battleships and numerous other craft sank, while 300 aircraft were destroyed or heavily damaged. Over 2,000 people died in the attack.

Yet, it did not bring the U.S. to its knees as Japan had hoped. All of the U.S. fleet's aircraft carriers were away from the harbor, while key sites like repair facilities and fuel depots were largely left intact. On December 8, President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his now-famous speech to Congress in which he called December 7 "a date which will live in infamy." Congress approved Roosevelt's declaration of war against Japan shortly thereafter. Three days later, Japanese allies Italy and Germany declared war against the U.S. The Americans had officially joined the war.

Decades later, there are still confusing things about World War II and the Pearl Harbor attack in particular that draw attention. First, there's Japan's decision to strike the U.S. in the first place, which certainly seems like a poor choice considering its later defeat. Moreover, details of the leadup to the attack and U.S. planning (or lack thereof) leave many wondering just what everyone involved was thinking.

Why did Japan decide to attack Pearl Harbor?

Upon first glance, it may look as if Japanese commanders made a stupendously reckless and unprovoked decision to strike Pearl Harbor. Yet Japan's motivations were far more complicated. Its leaders had an eye on imperial expansion and, when the U.S. began imposing sanctions and otherwise blocking the other country, this was poorly received. Japan's attack at Pearl Harbor was an attempt to get the U.S. off its back, allowing Japan to continue its expansion, secure vital resources like oil and metal, and establish itself as a major power.

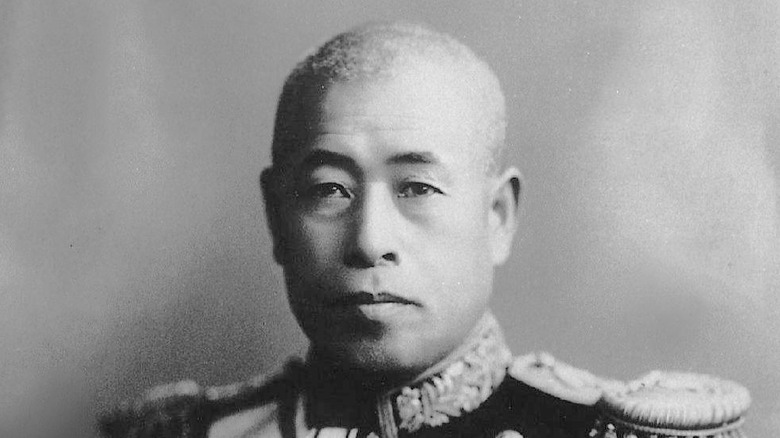

Even within Japan, part of the attack's disturbing history is that there was much back-and-forth prior to the strike, with war-hungry nationalists favoring action and more moderate voices expressing serious doubts. This last group included the commander in chief of Japan's Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who warned that an extended war would destroy Japan. He said the only chance was an intense, sudden attack that so thoroughly destabilized the U.S. it couldn't retaliate. But, after the attack saw the U.S. declare war against Japan and officially join World War II, it was clear to Yamamoto that things had gone poorly and they now faced a seriously messed up aftermath to the war. "I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve," he reportedly wrote in his diary (though the ominous statement may have really come from the screenplay for 1970's "Tora! Tora! Tora!").

Was the attack really inspired by a speculative novel?

The idea that the Pearl Harbor attack was inspired by a work of fiction may seem so nonsensical that you'd immediately dismiss it ... but don't be quite so hasty. The novel in question is "The Great Pacific War," which hit the market in 1925, 16 years before the Pearl Harbor attack. In it, author Hector C. Bywater wrote of what may have seemed downright fantastical to some at the time: a war between Japan and the U.S. It contains what are now eerie parallels with the real-life 1941 attack. In Bywater's work, Japan launches a surprise strike on the U.S. and, while it doesn't take control of Hawaii, it does command numerous other locations in the Pacific that help it establish a serious hold in the region. Yet the U.S. looks to take on an island-hopping strategy of amphibious warfare that could lead to Japan's defeat anyway.

Though this connection is speculative, it's hard to ignore the similarities between novel and real life. What's more, the architect of the attack, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, was stationed at the Japanese embassy in Washington, D.C. at the time of the novel's publication. Just a couple of years later, he was delivering speeches and holding discussions that paralleled many of Bywater's plot points. In fact, Yamamoto met with Bywater himself in 1934 London, where the two spent an evening discussing — what else? — a hypothetical war in the Pacific theater.

Why didn't U.S. military commanders communicate better?

The popular narrative of the Pearl Harbor attack is that it took everyone unawares. While many were aware of Japanese expansionism and increasing tensions between Japan and the U.S., the idea of a sudden attack simply wasn't on most minds. Yet, when it comes to at least some military commanders, their high-level picture of the situation makes their relative inaction confusing. Why didn't they read the writing on the wall and more obviously discuss how the U.S. was going to be drawn into the war?

Perhaps part of the problem was that command — and therefore, communication — was often divided. General Walter C. Short was in charge of the Army stationed in Hawaii, while Admiral Husband E. Kimmel commanded the Pacific Fleet. What's more, Short and Kimmel didn't always communicate for security reasons. This meant that, when Kimmel's Navy intelligence lost track of a steadily growing Japanese fleet less than two weeks before the attack, he didn't let Short know. Neither of the two commanders were able to set up an effective cross-department communications network, leaving key radar stations short-staffed and poorly informed of Navy aircraft maneuvers. Even then, surveillance managed to pick up suspicious Japanese activity, including aircraft launches and the appearance of miniature Japanese submarines near Pearl Harbor shortly before the attack, though slow communications and sluggish response times meant these early warnings made little difference.

Why didn't U.S. officials prepare more thoroughly?

Even with the major miscommunications between military branches, it's hard to understand why both Army General Walter C. Short and Navy Admiral Husband E. Kimmel didn't do more to prepare for an attack. They were well aware of tensions with Japan, which had been escalating since at least the late 1930s and had grown even more heated in the last year. Shortly before the attack, American intelligence indicated Japanese ships were moving in the direction of Southeast Asia, hinting at a troop buildup.

What's more, Japan had even outright warned the Americans ... kind of. As Japan continued negotiating, U.S. forces had received three warnings from their own government in 1941, on October 16, November 24, and November 27. That last warning, which came barely a week before the December 7 attack, baldly told Kimmel that "This is a war warning." He was instructed to "execute an appropriate defensive deployment," though the missive didn't contain details about dates or potential target sites (via U.S. Naval Institute). Yet Kimmel and his staff declined to put reconnaissance aircraft into action, in part because they interpreted the message as warning of a general attack by Japan somewhere else and not a movement specifically aimed at Hawaii. Meanwhile, Short ordered that Army planes should be closely grouped together at the island's Wheeler Field. He apparently meant to protect them from damage, but this also increased the efficiency of enemy attacks in damaging the craft.

Why were so many military officials convinced an attack would happen elsewhere?

Leading up to Pearl Harbor, at least some of the top U.S. military officials knew that the Japanese were mustering for an attack. But an attack on U.S. territory? That was apparently quite the mental leap. To be fair, previous intelligence efforts had indicated that Japan's navy was mostly interested in defense. Yet, U.S. forces in the Hawaiian islands didn't seem to even entertain the notion, with no practice drills or war games playing out such a scenario.

Try to put yourself in the mind of a military commander in 1941. You know that Japan is assembling a fleet and will attack somewhere. But why would Japan strike against the U.S., which admittedly had a rather small but growing military in response to increasing global tensions? Besides, weren't there more resource-rich territories to attack? British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia had all sorts of things the Japanese might want, including oil, ore, and rubber. Plus, those colonies (including American outposts in the Philippines) were much closer to Japan.

Others suspected a possible confrontation in the Marshall or Caroline Islands, still significantly east of Hawaii. Surely, many must have reasoned, Pearl Harbor was just too risky or inconvenient of a target. But U.S. officials didn't account for the possibility that their Japanese counterparts would break from the mold and agree to enact a daring, dangerous, and deadly attack.

How did the Japanese fleet manage to cross an ocean practically undetected?

By the time Japanese forces actually began moving across the Pacific towards Pearl Harbor, the attack fleet had grown seriously large. It included six of the nation's best aircraft carriers and more than 420 planes, accompanied by an array of other ships meant for a variety of purposes, from attacking the U.S. to refueling the fleet. All told, it was the largest attack force assembled by Japan. So, how did such a massive group of craft manage to make it 3,500 miles from Hitokappu Bay (now Kasatka Bay in the Kuril Islands between Japan and mainland Russia) to their position 230 miles north of Oahu practically undetected?

Part of the plan involved intense preparation, which included monitoring U.S. communications and military movements. Training areas were also closely guarded, with foreign vessels escorted out of sensitive areas and censoring of navy-related stories rampant.

Extreme secrecy was central, too. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the attack, did not inform many of his military compatriots of the plan. The ships were then sent on a far northern route that was meant to keep them out of shipping lanes. For further security, no radio communications were allowed, leaving personnel on the ships to communicate via lights or flags. It also helped that the ocean is extremely large and contained plenty of room for Yamamoto and his associates to map a route that keep such a large force out of sight.

How do you just lose track of Japanese aircraft carriers?

People have already wondered about how the Japanese fleet made it to Honolulu more or less undetected, but there's another facet to this situation that poses its own question: how did the U.S. lose track of the group? U.S. Navy intelligence did have a lock on the fleet ... until it didn't.

More specifically, radio monitoring lost track of the building group of enemy ships in mid-November, shortly before the Japanese fleet began sailing for Pearl Harbor. The likely explanation is that Japan tightened its radio security, and there were few other avenues for intelligence — it's not as if anyone had drones or digital footprints back then — so the U.S. lost track. Still, it's odd that no one seemed much alarmed, even though they acknowledged Japan was up to something. Even worse, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, who was in command of the U.S. Pacific fleet, did not communicate this quasi-disappearance to his counterpart in charge of the Army in Hawaii, General Walter C. Short.

The U.S. had actually been monitoring Japan for quite some time. Beginning in the late 1920s, America had been keeping an eye on Japanese radio communication. But analysts had concluded that Japanese naval forces were mostly interested in defense and were most likely to strike in Southeast Asia. If the U.S. had managed to regain monitoring of the fleet — admittedly pretty difficult — they would have seen the group moving east instead.

Why did radar operators misinterpret incoming Japanese planes?

There's very little evidence that the U.S. chain of command had any real, concrete indication of a coming Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor until too late. Sure, there were rumblings of conflict, which some higher-ups interpreted as a sign that Japan was likely to strike U.S. bases Philippines or perhaps in Borneo — but not in the U.S., they thought.

There was one key point where a different decision could have changed everything — and it came at a mobile radar unit stationed on the northern coast of Oahu. There, Privates Joseph L. Lockard and George E. Elliott Jr. were told to sit inside the unit van between 4:00 and 7:00 a.m. Though Lockard was in charge of the unit's oscilloscope, Elliott briefly took over near the end of their shift for practice. Just after 7:00, he detected a blip on the scan that indicated a large number of incoming aircraft, perhaps 50 or even more approaching the area from about 137 miles north. But, with such technology still in its infancy (in fact, World War II helped advance radar and other technology), neither private could tell exactly how many planes were approaching and where they were heading.

Lockard called the Army information center, where he reached Private Joseph P. McDonald. When McDonald consulted with the lieutenant on duty, however, the officer repeatedly told him that it was probably just a group of American planes and instructed them to ignore the signal.

Why did Kimmel skip so many patrols around Oahu?

Prior to Pearl Harbor, the military patrolled the area around Oahu, but curiously enough, those sweeps only concerned themselves with the southwestern bits of the coast. If either Naval Commander Admiral Husband E. Kimmel or Army General Walter C. Short had sent something in the other direction, perhaps they would have spotted the Japanese fleet stationed about 230 miles north of Oahu.

So, why didn't anyone do just that? The U.S. government did issue "War Warnings" to Kimmel throughout the fall and winter of that year, including a November 27 warning that some have since interpreted to mean he should have sent more aircraft out. But his interpretation of those warnings, along with a lack of intelligence information from Washington, D.C., led Kimmel to follow a more standardized war plan focused on the Philippines — which Spain had basically sold to the U.S. in the 19th century — or elsewhere closer to Southeast Asia. He was also specifically warned to avoid alarming civilians, which an increase in patrols could easily do. Though his mistakes aren't exactly excused, Kimmel was operating under military commands to prepare for battle elsewhere.

Moreover, an agreement signed by Short in April 1941 meant decisions about long-range reconnaissance were the responsibility of Rear Admiral Claude C. Bloch, Commandant of the 14th Naval District. Short's Army Air Force would defend the airspace around Oahu, but he wasn't necessarily in the decision-making circle anymore. In fact, he was reportedly more worried about a "fifth column" strike that could come from the local population.

Why did Japan's sub deployment fail at Pearl Harbor?

The Zeros and other planes that rained munitions down on the U.S. fleet weren't the first Japanese craft to reach Pearl Harbor. That distinction went to the military's newly developed miniature submarines, popularly referred as "midget subs." The craft were about 78 feet long and designed to handle the shallow waters of the harbor. Each carried just two sailors and two supercharged torpedoes, as well as weapons the crew were expected to use on themselves in case of capture.

But some Japanese commanders were nervous about sending the subs ahead of the fleet. If spotted, one could give away the plan. The quartermaster of the U.S.S. Condor did just that when he noticed a periscope peeking out of the water shortly before 4:00 a.m. on December 7. By 6:45 a.m., the destroyer U.S.S. Ward fired on the sub and sank it. The report had barely made its way to Admiral Husband E. Kimmel when the attack began.

The subs experienced near-total failure. Four of the original group of five subs sank in battle that day, due to strikes or mechanical failure. The only one to survive was plagued by malfunctioning equipment — perhaps the ultimate explanation for the defeat. When sailors scuttled it, one drowned while the other, Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki, washed up on a nearby beach and soon encountered U.S. Corporal David M. Akui. Sakamaki became the first prisoner of war captured by the U.S. in the conflict.

Why did one Japanese commander mess up a vital signal?

Though the Pearl Harbor attack was devastating, it could have been far worse. But why wasn't it? It has to do with flares. Commander Mitsuo Fuchida was in charge of tactical decisions for the first wave. There were two possible plans: one if the Americans were surprised, and another if U.S. forces caught on before the attack. One flare would signal a surprise attack and two indicated a more cautious "no surprise" plan.

Though the U.S. was unaware, Fuchida fired two flares. He later claimed to have fired one but, thinking it was a dud, set off another. Yet, given the complexity of loading and firing flare cartridges from the cockpit, Fuchida may have meant to fire two all along. He certainly never seems to have corrected this mistake. In an even odder detail, this plan was never communicated via radio, though other commands were relayed between Japanese planes in this way.

Perhaps commanders had believed that torpedo bombers, considered key to the success of the attack, would have been left vulnerable in a surprise-style plan. In that scenario, the torpedo bombers would have attacked first, followed soon after by dive bombers. It could also be that Fuchida lied because the attack became an uncoordinated mess that did not strike the Americans as hard as originally intended. In attempting to cover for himself, he may have been trying to shift the blame for the mix-ups that day onto other commanders.

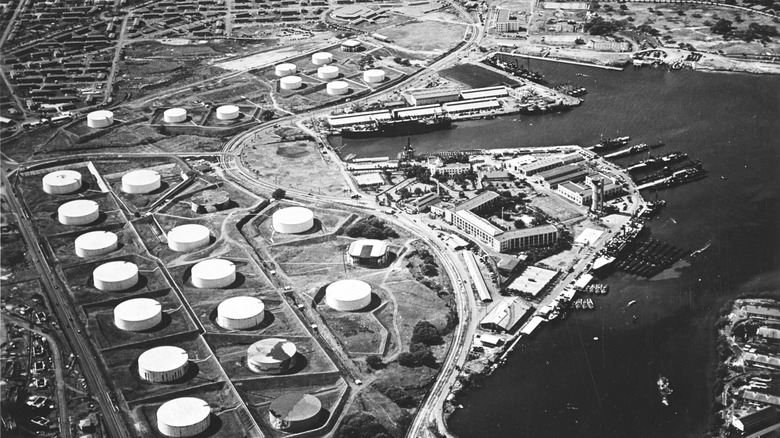

Why did Japanese fighters miss U.S. fuel depots?

During the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese planes struck several U.S. ships, yet there was an odd oversight: the fuel tanks. That the largely exposed tanks remained mostly intact was already strange, but it gets odder when you realize that Pearl Harbor was basically the only U.S. military refueling station in the region. If Japan had managed to destroy the fuel, such a loss could have dramatically hampered the U.S. recovery. What's more, they also missed the USS Neosho, a fleet oil tanker whose destruction would have been likewise devastating. Even odder was the matter of the pre-existing oil embargo. In response to Japan's aggressive expansion into China, FDR cut off key avenues of trade between the U.S. and Japan — including the one that supplied about 80% of Japan's oil. One can imagine that a strike on such a major U.S. fuel depot would carry great symbolic as well as strategic weight.

Perhaps Japanese Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, in charge of the main carrier battle group, was overly focused on striking battleships and aircraft. He and other commanders that day also seemed especially eager to get the attack over with. That's understandable to an extent, as lingering might not have done the Japanese much good as part of a sudden surprise attack. Yet, a little more time and flexibility may have dramatically changed the Japanese plan of attack, the state of that fuel, and the course of the war.

Why wasn't there a direct line between Hawaii and D.C., anyway?

When it came to communication during the infamous events of December 7, 1941, there was already the major issue of how the different branches of the military stationed at Pearl Harbor communicated with one another (in a word: poorly). But there was yet another speed bump: there was no direct line between Pearl Harbor and Washington, D.C. However, that's perhaps not entirely fair, as the communications technology of 1941 wasn't exactly on par with the ultra-fast technology of today.

The morning of the attack, officials in Washington received word that a Japanese force was approaching Pearl Harbor mere minutes before the attack began. With the communications delay, personnel at Pearl Harbor were none the wiser. When D.C. received the sensitive information, it had to send it via telegram for security's sake, but because it was Sunday, many telegram offices were closed. When the message finally got to Honolulu, it still had to make its way to a military command post ... via bicycle courier.

Said cyclist had to take cover as the attack began, but managed to bring the message to Fort Shafter just before noon. By the time it was decoded and in the correct hands, it was nearly 3 p.m., and the Japanese planes were gone. If the military and U.S. government had somehow been able to manage better communications — imagine Roosevelt simply being able to telephone Kimmel or Short — personnel at Pearl Harbor could have been given a critical heads-up.

How come so many aircraft carriers were away from the harbor?

One of the saving graces of the Pearl Harbor attack was that no U.S. aircraft carriers were in port. This made Japan's sudden, targeted attack far less successful, considering some of those key targets were elsewhere. When the aircraft carriers and their personnel returned, they were certainly an asset to America's relatively fast response and now far more motivated entry into the war.

How did such a stroke of luck happen? At the time, the U.S. Navy had three aircraft carriers in the Pacific Fleet (four others were in the Atlantic), and each one was away on a mission to bolster U.S. support elsewhere in the Pacific region. The closest at the time of the attack, the USS Enterprise, had gone to Wake Island with 12 fighter planes, and was on its way back to Pearl Harbor when it got word of the attack. Eighteen fighters were launched from the Enterprise and were part of the American defense (though some were shot down by friendly fire). The USS Lexington was hundreds of miles away on a similar mission, while the USS Saratoga was picking up troops and aircraft in San Diego.

And, yes, the Japanese commanders were well aware that all three carriers were coincidentally away, but thought the many battleships at Pearl Harbor were a better target. Yet, as the carriers proved vital to ferrying aircraft and military personnel, it eventually became clear that this was a major miscalculation.

How did Japan keep all its planning secret?

How did Japan keep its plans so secret? Consider the task: Japan launched 354 planes, while the rest of its attack force included six aircraft carriers, two battleships, and 23 submarines, among many other naval craft. That's a lot to bring together without someone noticing. Japan achieved its surprise by picking an especially quiet cross-Pacific route, locking down radio communications, censoring news, and engaging in intensive training. Even the Prime Minister of Japan and departments like the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Japan's Army were unaware that Pearl Harbor was in the nation's sights.

However, Japan's security wasn't perfect. The U.S. had broken Japan's diplomatic cipher and was working on the more information-heavy military ciphers (but obviously didn't get there before the Pearl Harbor attack). However, it bears repeating — there was no forewarning conspiracy in which anyone but Japan knew about the attack in advance. Instead, the U.S. consistently underestimated the other nation's abilities and willingness to attack other nations.

As the war progressed, Japan's intelligence security began to break down. Ahead of the Battle of Midway, the Allies broke ciphers used by the Japanese Navy, giving them a major advantage. Japanese commanders ignored hints that the code had been broken and experienced major defeats not just at Midway, but also at the Battle of the Coral Sea. Broken codes and intercepted documents were bad, but Japan's lack of counterintelligence proved at least as harmful, while its weak response to such breaches was confusing.

How did the Americans manage to respond so quickly?

The whole point of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor was to kneecap the United States. If the barrage was thorough enough, reasoned Japanese strategists, the Americans would be so overwhelmed by rebuilding that they could offer no resistance to Japan as it continued on its empire-building ventures. Yet, in the space of just six months, the U.S. went from Pearl Harbor to the Battle of Midway, where it so thoroughly defeated a Japanese fleet that many now consider it one of the most important battles of World War II.

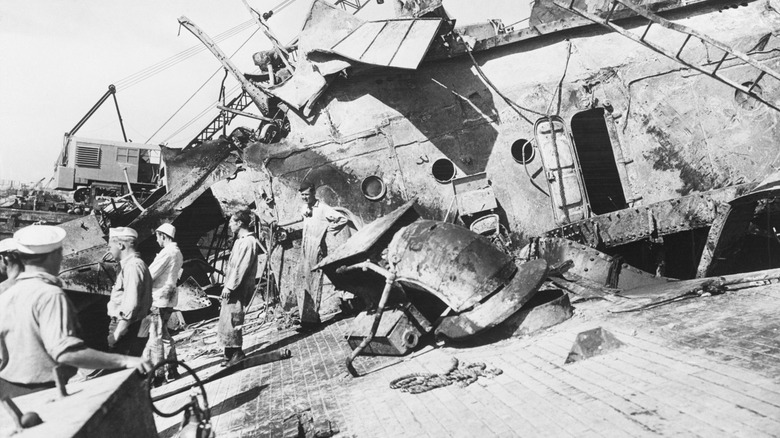

So, what made the difference? In a strange way, the Japanese gave the Americans a leg up, making strategic errors such as leaving drydock repair facilities largely untouched. Likewise, fighter pilots never really circled around to strike clearly visible fuel depots or search for any major ships not in the harbor. And what did remain in the waters of Pearl Harbor wasn't necessarily there for long.

Salvage operations began almost immediately afterward, with repair crews able to get one ship, the USS Nevada, back on the water the following February, and on active duty by the end of 1942. Other ships were also raised, though some (such as the heavily damaged USS Arizona and USS Utah) remain in Pearl Harbor to this day. U.S. service members and civilians alike were also certainly more motivated to join in the war effort and avenge the deaths of those who fell at Pearl Harbor.

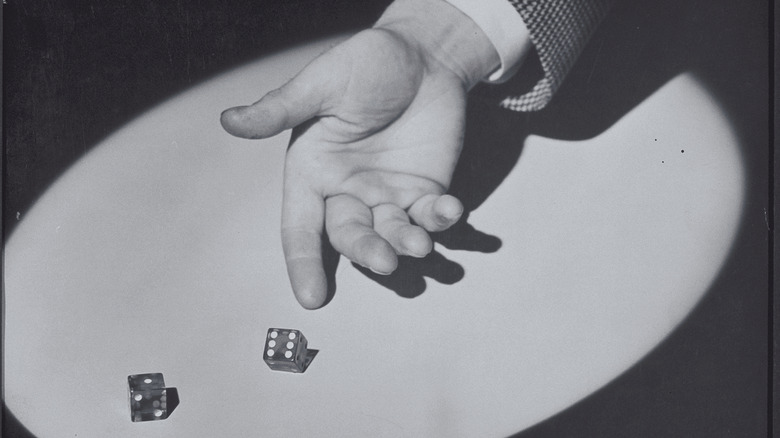

What was going on with that dice game ad?

In the whole story of the Pearl Harbor attack, perhaps few things are weirder than a magazine ad. The oddness began when a November 1941 edition of the New Yorker ran an advertisement showing people happily playing a dice game ... in an air raid shelter? It was a bit strange, especially given that the game was rather ominously named "The Deadly Double." Actually, this was a series of ads in the issue, with six small tags throughout the magazine referring back to the main image of a jarringly cheerful group playing the game belowground. Those tag ads sometimes included dice bearing 12 and seven; not numbers you'd see on a standard six-sided die.

The story goes that this ad was actually some sort of warning that Pearl Harbor was going to be struck, bolstered by the fact that the attack took place on December 7 (12/7, if you will). Supposedly, the ad was given to the printers in person and paid for in cash, leaving investigators with few leads. Only, there absolutely were leads, they just didn't create a flashy story of international conspiracy.

Instead, the ads were all just a bizarre coincidence of many in WWII, according to the widow of Roger Paul Craig, the game's creator. She spoke out against the conspiracy when it came back around in the 1960s. Previously, Craig himself spoke to the Los Angeles Times in May 1942, publicly decrying what he saw as a ridiculous rumor.

Why do people still believe in a forewarning conspiracy?

If there's one persistent misconception about Pearl Harbor, it's surely the forewarning conspiracy. In its most basic form, this maintains that President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other high-level government officials knew darn well that Japan was set to rain devastation down upon Pearl Harbor. Yet, they said and did nothing, hoping to both bring the U.S. into the war and keep a flagging Britain in the conflict. Plus, with the U.S. officially in the war, it would be able to more overtly aid allies in the fight against the Axis Powers.

But, as much as someone may find conspiracy stories compelling, in this case it's definitely just a story. While there are some elements of truth to it (including evidence that U.S. officials expected some sort of warlike action from the Japanese military), the idea that Roosevelt would allow a highly destructive attack to hit a significant portion of the Pacific fleet simply doesn't make sense — especially if the U.S. planned to join the war afterward. Why wouldn't Roosevelt have just declared war, even if his popularity took a hit? The attack also meant that the U.S. was now effectively engaged in two theaters of war, with a complicated and consuming front on the Pacific in addition to the European side of the conflict. Indeed, American warships were redirected from the Atlantic, leaving some British operations vulnerable as the U.S. shifted a major portion of its focus to the west.

Why were some service members' remains left in sunken ships?

In the Pearl Harbor attack, 2,404 people were killed on the U.S. side, including 68 civilians and 1,177 on the U.S.S. Arizona alone. Five battleships sank in the harbor, as well as three destroyers and a training ship. Many more suffered serious damage.

While some survived the attack, one of the most horrifying details of what happened to the bodies at Pearl Harbor centers on those trapped in wrecked ships. Afterward, some reported hearing the taps and bangs of sailors trapped inside, while the salvage crew that raised the remains of the U.S.S. West Virginia reportedly found the remains of sailors and a calendar indicating that they had marked off a chilling 16 days stuck inside. It took decades for the U.S. Navy to admit the details of this story to the sailors' families.

But how could sailors be left inside a wrecked battleship for over two weeks? While crews worked desperately to save service members in the wreckage, they were presented with some seriously difficult choices. The area was often coated with fuel leaking from mangled ships, meaning attempts to cut through metal decking could spark a deadly blaze. Likewise, creating an opening in the wrong spot could flood the interior. For similar reasons, over 900 bodies were left behind in the U.S.S. Arizona and declared "buried at sea." Survivors of the sinking may also be buried in the wreckage. To date, 44 service members have been interred there after the attack.

Why is the USS Arizona still leaking oil?

If you visit the Pearl Harbor National Memorial today, you will likely be able to take a small boat out to the USS Arizona Memorial, a white structure in the harbor that sits just above the wrecked ship of the same name. Look over the side and you may spot a slick of oil floating atop the water. This is fuel leaking from the USS Arizona, which it's been doing ever since it sank.

Sure, this isn't on the scale of the chilling Exxon Valdez oil spill, but why has all that oil been allowed to seep out of a shipwreck for over 80 years? More specifically, the USS Arizona still contains thousands of tons of oil, with about two quarts leaking every day. Of course, there's the deeply-held symbolic importance of the wreck, which is not just a memorial but also a graveyard containing the remains of sailors who died that day, as well as a number of survivors who were later laid to rest there. Disturbing that final resting place is not something to take lightly.

The other reason the oil is still there is actually directly connected to environmental concerns. If some agency were to try and remove the remaining oil, there's a chance that it could leak out all at once and cause a major environmental disaster. For the time being, careful monitoring of the USS Arizona and its oil is considered the safest and most respectful thing to do.

Should Kimmel really get so much of the blame?

Who bears the blame for Pearl Harbor? For many, it's U.S. Navy Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, who was the senior military officer on Oahu. Yet, Army General Walter Short was in charge of defending the island of Oahu and its military bases. Meanwhile, Rear Admiral Claude C. Bloch was also one of the main decision-makers when it came to long-range reconnaissance. Kimmel also sometimes met with resistance from the U.S. government, which repeatedly took vessels from his Pacific fleet to face off with German U-boats in the Atlantic.

Kimmel also did not have potentially important decoding equipment for intercepted Japanese diplomatic communications — but those in D.C., the Philippines, and elsewhere did, indicating that someone thought it was worthwhile. In 1945, TIME reported that a military inquiry had also found other blame-bearers, among them Admiral Harold "Betty" Stark, then Chief of Naval Operations at Pearl Harbor. Stark had routinely steered Kimmel away from considering a Japanese attack on Oahu, and perhaps even failed to deliver information that would have pushed him in the other direction.

Certainly, Kimmel is not free of responsibility. He was in a position where, had he made other decisions (perhaps increasing patrols or stepping up readiness drills), Pearl Harbor could have looked very different. But does it make sense to pin him as the major blunderer? Perhaps it did to officials in Washington, who needed a pair of scapegoats in Kimmel and Short, and maybe didn't want the same level of attention turned to their own mistakes