Things About Japan's WWII Strategy That Don't Make Sense

If you looked at a map of the Pacific theater in early 1942, you might think Japan had the war all but won. They held Southeast Asia and big swathes of China, along with a constellation of smaller Pacific islands that pushed the battlefront far from the Japanese home islands. The U.S. Pacific fleet had been sucker-punched, the European powers whose colonies Japan was gobbling were distracted by Germans at home, and there was seemingly little in Tokyo's way.

Unfortunately for Japan's war strategists, their plans for conquest rested on some optimistic and faulty assumptions, and 1942 would see the high-water mark of the empire. Over the next three years, U.S. and allied forces would roll back Japan's conquests, and the cities of the home islands would come under devastating aerial assaults, including the only two hostile detonations of atomic weapons thus far. Unrealistic goals, pride, and an unwillingness to confront certain truths had doomed the Japanese war machine.

They faced resistance within Korea

In 1910, Japan forcibly annexed the Korean Empire, corresponding to modern-day North and South Korea. Western powers permitted the conquest, given that they were more interested in Japan countering Russia than they were in the rights of the Koreans. This prompted the beginning of a harsh rule over the peninsula and its people, which saw individuals and communities stripped of their lands, names forcibly changed, and cultural expression quashed.

Agitation for independence was bloodily crushed in 1919, but unrest continued, with spikes in 1926 and 1929. Japan reimposed military rule in 1931, and anyone maintaining order "at home," as the Japanese saw it, could not be used in the war abroad. As the war against China and later the Western allies began in earnest, the Japanese tried to tighten control over Korea, drafting Korean civilians for forced labor. Later, they were impressed into the Japanese army itself.

The Korean government in exile in Chongqing, China, pulled together an army of Korean exiles and existing resistance groups called the Korean Liberation Army. While not a major force, it received training from the U.S. armed forces and faced the Japanese on the Indian and Burmese fronts. A separate Soviet-sponsored force carried out guerrilla warfare in Korea and Manchuria. In another generation, Korea might have been more fully incorporated into the Japanese state and a bigger help to the war effort, but as it was, the colony was at best an asset with dangerous strings attached.

Japan is not self sufficient

The Japanese main islands are mountainous and rocky, which make for lovely views but limit its arable land. Additionally, Japan at the dawn of World War II was reliant on other imports needed for an industrial economy or a major war effort, particularly petroleum and rubber. These scarcities partially drove Japan's imperial expansion, as it hoped to be able to conquer and hold areas that could provide these resources, like the oil-rich Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, and British Malaya, now Malaysia, which was so full of rubber plantations it could almost bounce.

Unfortunately for Japan, these limitations on self-sufficiency meant that it didn't have the resources to fight the long, grinding war of attrition that the Pacific theater became, so Japanese forces needed to land quick, Blitzkrieg-like blows to grab territory fast, with the goal of then turning the captured territory's assets to the war effort. And at first, this worked, with Japan expanding like a balloon in the early days of the Pacific War, but ultimately the better-resourced Allies were able to out-supply, out-repair, and outlast Japan.

Japan invaded China too soon

After gobbling Korea in 1910, Japan's next target for expansion was the neighboring Chinese region of Manchuria. After a number of years of meddling, Japan manufactured a pretext for an invasion in 1931 and quickly overran the territory. They found the last emperor of China, overthrown as a child in 1912, and popped him onto a paper throne as the new ruler of Manchukuo, an effectively imaginary empire: Real power was held by the Japanese.

The conquest of Manchuria seemed like a good opening salvo for the later invasion of China, especially because the sitting Chinese government was too weak to effectively resist it, but it brought problems along with benefits. Manchuria was full of people eager to sabotage and resist the Japanese when the opportunity presented itself.

Additionally, Japan's invasion of Manchuria, subsequent pressure on China, and the ultimate invasion in 1937 interrupted an ongoing civil war. The Nationalist government of China and communist rebels had been fighting a civil war since 1927, and Japan had been able to move freely in Northern China because Chinese leadership was more interested in fighting the communists. This changed when the scale of the upcoming invasion became clear, and in 1936 the government and the rebels formed a United Front, essentially agreeing to fight the Japanese first, and each other later. Had Japan let the two sides batter each other for longer, they might have faced far less resistance.

Japan had no local allies

In Europe, Germany and Italy were the big boys leading the Axis alliance structure during World War II, but they were aided by a number of smaller partners who were able to advance Axis war goals on the continent. Romania's Ion Antonescu was thrilled to participate in ethnic cleansing alongside Germany. Finland was willing to open another front against the Soviet Union and menace Leningrad. Hungary and Slovakia sent men to the Eastern Front.

Japan's allies in the Pacific were almost all its own puppet states. In occupied China, Vietnam, Burma, and the Philippines, Japan set up ostensibly friendly governments but it had to invade and occupy these territories first, which didn't really lead to a net gain of fighters. The only real state ally Japan notched during the war was the Kingdom of Thailand, which only joined the Axis under extreme duress (i.e. after a Japanese invasion). This alliance generated a Free Thai Movement that resisted the Japanese occupation and Thai involvement in the war.

Japan was also able to ally with an Indian independence movement called Azad Hind. The Azad Hind were reliant on Japanese support for their actions against British authorities, making it arguably more of a drain than an opportunity for overstretched Japanese forces.

Japan missed the opportunity to kick the Soviets when they were down

In the summer of 1941, Hitler's Germany embarked on its boldest offensive campaign yet: The invasion of the Soviet Union. Operation Barbarossa was a massive undertaking designed to destroy and dismember the Soviet state. It almost succeeded, but its failure was one of the most decisive turning points of the war.

Japan and the Soviet Union had agreed on a non-aggression pact in April 1941, but nonetheless, Japan had a detailed strategy for invading the Soviet Union. Plan Kantokuen was an extremely nasty set of ideas: Had Japan enacted it, they would have used chemical and biological weapons to soften Soviet resistance in the Far East, ultimately conquering a chunk of territory contiguous to Manchuria. This would obviously have pulled Soviet attention, men, and materiel away from the front in Eastern Europe and imperiled the desperate Soviet resistance.

But Japan, heavily involved in China and lusting after resource-rich territories to the south, decided against joining Hitler in a pincer against Russia. Instead, later that year, they would begin a war against the United States with the Pearl Harbor attack. By mid-1945, with the Americans closing in on Japan from the Pacific side, the Soviets were ready to help. Soviet forces swarmed Manchuria in August, making colossal gains in a matter of days. This reverse, along with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, finally drove the stake through the Japanese war machine's heart.

Pearl Harbor was not successful enough

At first glance, the Pearl Harbor attack seems like a bold but credible gambit. If Japan could obliterate the U.S. armory in the Pacific, it would buy time to consolidate its position while the U.S. rebuilt. Starting a war is inherently risky, but you can see how this strike-first, strike-hard idea had some appeal.

The plan failed because the attack failed — or at least, it didn't succeed well enough. Three American aircraft carriers were away from port during the Japanese assault, including the USS Enterprise (no relation), which became one of the U.S. fleet's most valuable assets during the war. Japanese attackers were also so invested in destroying ships and planes that they didn't attack fuel supplies or, um, repair stations, which were immediately useful in mitigating the attack's effects. Japan ultimately only fully destroyed three battleships, with other vessels left damaged but salvageable, and these craft were fixed and sent into the war against Japan as quickly as could be.

This blunted sucker-punch led directly to a near-worst-case outcome for Japan. The resource-rich but reluctant United States was now fully committed to war against Japan, which had failed even to buy much time when it struck the dozing giant. Japan was left defending a huge front when the United States came in from the top rope to wallop them back across the Pacific.

They were defending a huge front

By the time of U.S. entry into the Pacific war, Japan was left defending an absolutely gargantuan front, with active fighting in several theaters. Japan's force commitment by 1942 would have badly stretched even better-resourced war efforts, and as the war continued, Japan began to lose its fatal game of Whac-a-Mole.

When the Japanese Empire crested in 1942, it occupied all of Southeast Asia, Manchuria, Korea, a huge swath of Eastern China, nearly all of modern Indonesia, the Philippines, and a vast constellation of smaller islands extending far out into the Pacific. In addition to occupations, Japanese forces were actively fighting in China, along an Indo-Burmese front, and in the sweltering mountains of New Guinea. This is a lot, even without the invasion of Australia they almost undertook! The plan, or at last hope, was that Japan could establish and then reinforce a heavily armed perimeter far from the home islands that its enemies would balk at storming, layering such defenses if it needed to.

But as Japanese military planners soon learned, taking territory is not the same thing as holding it. Their admittedly awe-inspiring conquests of the early war left them badly stretched, just at the moment the heavily resourced United States was entering the war. Had they limited or prioritized their objectives, Japan's success might have been less transitory.

They didn't neutralize China in time

Japan's invasion of China beyond its Manchurian conquest was a brutal, appalling affair, with enormous loss of life on both sides and atrocities leveled against many, many Chinese civilians. The cruelty Japan had intended to break Chinese resistance only galvanized it, and though at its peak Japan occupied huge portions of China, it was never able to declare victory and turn its full attention to other theaters of war.

At the Japanese invasion, the contesting parties in the Chinese Civil War agreed to unite against Japan, denying Japan the chance to benefit as much as it might from internal divisions. Chinese leadership retreated to the west, with the government setting up a temporary capital at Chongqing from which it continued to direct the war. Japanese control was never as thorough as it looked on a map, with territories Japanese forces had passed through organizing resistance activities after they had left. Effective Japanese dominance was often limited to major towns and transit connections between them, like islands in a sea of angry rural Chinese fighters.

Though Japan controlled most of China's major ports for most of the war, China was usually able to receive supplies overland from British India until 1942, and even after the fall of Burma some help trickled in by air, by difficult overland routes, and by smuggling. And by early 1944, the United States was not only delivering material help but also training exiled Chinese fighters in India. China's years-long resistance paid off, sapping Japanese forces for the duration of the war.

Japan couldn't attack the United States homeland

While Japan was able to run riot across China, and while Britain, France, and the Netherlands were too distracted by the war in Europe to commit much power to defending their colonies, Japan's most powerful foe was out of its direct reach. While the United States could and did pummel Japan directly, Japanese efforts to retaliate never amounted to more than a nuisance.

As early as April 1942, the United States attacked the Japanese home islands. In the Doolittle Raids, an aircraft carrier brought specially modified American heavy bombers within 600 miles of the Japanese mainland. The planes were able to assault a number of Japanese cities, including Tokyo, before continuing on to land in allied-held China. The damage was not physically enormous but shook Japanese confidence, focusing military plans on the fatal attempt to take Midway in the hope of preventing further such assaults. This plan failed, and by the war's end over 60 Japanese cities, Tokyo among them, had been heavily bombed.

Japan was never seriously able to threaten the American homeland, though it did try. In late 1944, the Japanese military built 10,000 "fu-go" balloons to carry heavy explosives across the Pacific and detonate in the continental United States, intended to cause forest fires in the heavily wooded Pacific Northwest. The balloons were hard to launch and reliant on wind conditions: While some reached the United States, their total toll was six dead civilians and a power outage.

Japanese cities were vulnerable

Traditional Japanese architecture is, like many of the art forms of Japan, both beautiful and practical. Wooden construction makes use of the forests that make up one of Japan's few truly abundant natural resources, and the wood-and-paper walls and generally lightweight construction of these homes make them resilient in earthquakes through a degree of flexibility. These structures are easy to repair when necessary, with such repairs incorporated into the cultural role of the buildings.

These buildings are not resistant to aerial bombing raids. By the beginning of 1945, American bombers could fly basically unimpeded over Japan, regularly darkening its skies with showers of incendiary bombs. Some public buildings had been constructed along Western principles from the late 1800s, but Japanese cities still comprised huge, closely packed areas of flammable materials.

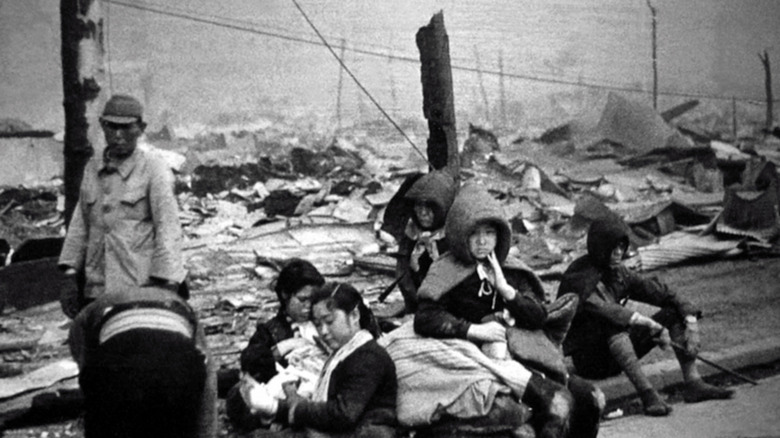

In the most deadly event of the war before the atomic bombs, over 300 American bombers left for Tokyo the evening of March 9, 1945. The resulting fires, sparked by colossal bombs full of napalm-like propellants and goaded by furious dry winds, scorched 15 square miles of Tokyo: The low estimate of deaths is nearly 90,000, with around a million left homeless. And this was only one night in a months-long campaign of firebombing that spared only five Japanese cities. One survivor was ancient Kyoto, and the other four, Hiroshima and Nagasaki among them, were left largely intact to better showcase the ruin if an atomic weapon were dropped.

Good old-fashioned hubris

Perhaps the most nonsensical aspect of Japan's war plan was its inherent optimism. Japanese war planners theoretically understood the country's weaknesses, including the critical issue of limited resources, but focused on the country's strengths to the extent of creating a false reality that governed their decision-making.

Japan bet heavily on winning a short war and, somehow, was willing to face the United States effectively alone in a long Pacific showdown that favored the more resilient power. While the United States did initially join its European Allies in liberating Europe from the Nazis and their flunkies, the Japanese had no guarantee of that approach and even with American attention divided, Japan was on the ropes when Germany surrendered in May 1945.

The miscalculations pile up. Japan thought the Soviets would be out of the war in 1942, which would let Japan reassign men stationed in Manchuria against a potential Soviet incursion. Japan calculated it could grow enough rice to meet the needs of an expanded, strained workforce and widely deployed military, but local shortfalls and effective blockades of food imports pushed the home islands into famine-like conditions by war's end. They expected the American Navy to only approach about 300,000 men by the end of 1943; the actual manpower confronting the empire topped 2 million. Japan planned for the war it hoped to fight, and it lost.