Weird Details People Ignore About These WWII Generals

One of the things your history class didn't teach you about World War II is how unusual many of the military leaders in charge of it were. Considering how many people fought in the conflict (an estimated 70 million were in the combined armed forces of all participating countries), it was always guaranteed that some of them would be a bit kooky. When it was a regular soldier or even a low-level officer who saw the world differently or lashed out at the drop of a hat or was always running off to look for birds, that was one thing. It's when these sorts of men made it all the way up the ranks that their strange foibles started affecting lots of soldiers.

Rather than the stoic, carved-from-a-log cliche of the military general, these men proved that the right person for the job of leading troops into battle might be flamboyant or literary or very, very angry. Perhaps the type of brain that is best equipped to lead an army is never going to be completely normal, and the various eccentricities of these brilliant but wildly different men led to plenty of World War II stories that sound fake, but aren't.

Sometimes their personalities only affected their private lives, and sometimes they changed the course of the war. Here are some weird details people ignore about these World War II generals.

General George Patton

While there were plenty of strange rules soldiers followed during World War II, considering the reality of the stress on the front lines, some of the less important regulations were often allowed to slide. However, if you served under General Patton, your uniform was going to be up to code every single day. This included the order that officers wear their regulation neckties into battle. He is alleged to have said, "How can we trust our soldiers to fight our wars if we cannot trust them to wear their uniform properly?" (via U.S. Air Forces Central). His uniform rules were so infamous that they were pilloried in wartime satirical cartoons in the military's Stars and Stripes magazine.

Despite this, Major General Omar Brady believed the requirements were overall positive, since, as he said, "Each time a soldier knotted his necktie, threaded his leggings, and buckled on his heavy steel helmet, he was forcibly reminded that Patton had come to command the II Corps ... and that a tough new era had begun" although he admitted the rules did "little to increase [Patton's] popularity..." (via "General George S. Patton and the Art of Leadership: One of America's Greatest Ever Generals").

Unfortunately, another one of Patton's quirks was that he did not believe in PTSD (then known as shell shock). In two separate incidents, when encountering physically fit soldiers with the serious mental condition in a hospital, the general slapped and yelled at the men. He was severely reprimanded for this abuse.

General Sir Harold Alexander

General Sir Harold Alexander (later promoted to field marshal) was what his countrymen might call a "jolly good chap." Alexander, known as "Alex," was considered the perfect English gentleman by his peers, and his poise and good manners got him far in life, not least of which in the military. However, this extremely old-world sense of decorum did lead to some strange situations when transferred to the front lines.

After having dinner with Alexander, future Prime Minister Harold Macmillan wrote in his diary that despite what was happening outside the mess hall, the general's chosen topics of discussion at the meal included "the campaigns of [military commander of the Byzantine Empire] Belisarius, the advantages of classical over Gothic architecture, [and] the best way to drive pheasants in flat country ... There was no fuss, no worry, no anxiety — and a great battle in progress!" (via "Tug of War: The Battle for Italy, 1943–1945").

While the ability to discourse on such topics might sound impressive, as people got to know Alexander more — or were forced to work alongside him — they often grew concerned that his calm, genial manner was simply good cover for the fact that he was incredibly stupid. Fellow generals were not shy about the fact that they believed he was anything from just plain incompetent to wholly reliant on his subordinates to do any actual thinking that his job required. Regardless, Alexander's success and reputation continued to increase after the war.

Major General Dr. Brock Chisholm

Major General Dr. Brock Chisholm was the Canadian director general of medical services during World War II. While he seemed to have gotten through the conflict without weirding anyone out, he made up for that immediately after the war ended. It seems the medical-military man felt quite emphatically that children who believed in Santa would be the downfall of civilization.

No, really. In a 1945 speech, Chisholm said, "Any man who tells his son that the sun goes to bed at night is contributing directly to the next war ... Any child who believes in Santa Claus has had his ability to think permanently destroyed ... He will become a man who has ulcers at 40, develops a sore back when there is a tough job to do, and refuses to think realistically when war threatens" (via Literary Review of Canada). When given the chance to walk back these comments, Chisholm instead doubled down, telling a reporter, "Santa Claus was one of the worst offenders against clear thinking and so an offence against peace."

While Santa had the majority of his ire, Chisholm — a founder and the first director-general of the World Health Organization — also hated superstitions. "It is a terrible fact that there is hardly a hotel in New York that has a floor numbered 13. The implications of this are enormous and disturbing, and nobody is doing anything about it," Chisholm opined in a 1946 speech, according to The New York Times.

General Bernard Montgomery

Considered by some to be on the shortlist for worst generals of World War II, General Bernard "Monty" Montgomery was not a wholly unsuccessful commander, at least when it came to what he achieved on the battlefield. For those who had to interact with him, however, the man was a complete disaster.

The general (later field marshal) was blunt to the point of rudeness with everyone, even his superior officers. In his diaries, General Sir Alan Brooke wrote of one interaction with Montgomery, "I had to haul him over the coals for his usual lack of tact and egotistical outlook which prevented him from appreciating other people's feelings" (via Kevin Telfer's "The Summer of '45: Stories and Voices from VE Day to VJ Day"). Perhaps the most striking example was when Montgomery's own stepson escaped a German POW camp and made it back to the Allied lines. According to The Sunday Times, Montgomery's first words to him were "Where the hell have you been?" This apparent inability to interpret social cues has led some historians to speculate that the general may have been on the autism spectrum.

Montgomery's behavior even caused a rift between the Allies. An American general made a bet with him that was clearly intended as a joke, but Monty won the bet and insisted on receiving the prize — a B-17 Flying Fortress as his personal transport. His refusal to back down meant General Dwight Eisenhower was forced to make the rare and coveted aircraft available for Montgomery.

General Douglas MacArthur

General Douglas MacArthur was a complicated man. Undoubtedly a brilliant general and military tactician, he was also a massive egotist who was obsessed with projecting a certain image. Perhaps nothing sums up this part of his personality more than MacArthur's famous corn cob pipes. Most of the iconic pictures of the general (which he was always happy to take, if not insistent on), show him with the large, oddly shaped pipe clamped firmly between his lips. The pipes are impossible to miss and have become iconic, forever connected with the general.

This was all part of MacArthur's plan; he designed the pipe himself and sent the specifications to the Missouri Meerschaum company. After a bit of back and forth between the general and the company on the design, it produced the "MacArthur 5-Star Corn Cob Pipe," which is still in production today. "When the company's staff at the time sent him that creation, he was delighted and would rarely be seen in a photograph without it," Meerschaum's General Manager Phil Morgan told Missouri Life. While functional, the corn cobs did not actually make for good smoking pipes, and anyway, MacArthur preferred cigarettes in private.

Even after he was ingloriously relieved of his command during the Korean War, MacArthur continued to use his iconic pipes. The Meerschaum company still has a letter MacArthur sent to its owner in 1959 saying, "With the passage of time, I find each year brings increasing enjoyment of my corncob pipes."

General Sir Alan Brooke

Battlefields are probably not the best place to go looking for birds, what with all the loud bangs scaring them off. But if General Sir Alan Brooke ever found himself in that situation, you can be sure that one eye would be scanning the skies, just in case. The general (later field marshal) was an obsessive bird watcher.

While Brooke was a dedicated soldier and Winston Churchill's right-hand man during the war, he was not one to miss the opportunity to do something bird-related, no matter what else was going on. Churchill generally took a nap in the afternoon, and once Brooke realized this, he used that time to sneak off and buy books on ornithology. Under constant guard when at the Kremlin, the general's Soviet security was once forced to chase after him when Brooke went looking for a black woodpecker.

After the war, Brooke had any number of incredible stories he could tell, including being in the room with Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, and Josef Stalin when world-altering decisions were made. Despite this, if you got to chatting with him, he was more likely to start talking about birds than the historic moments he had been witness to. However, his obsession also served to humanize the general. Brooke's biographer, Andrew Sangster, told Key Military, "I was ... bemused by his love of birds, and not until reading another ornithologist's autobiography did I realize that Brooke was really capable of fun and laughter like the rest of us."

Lieutenant General Lewis Brereton

Today, flying is one of the safest forms of travel, but this was not the case a hundred years ago, and certainly not when it involved military fighter pilots. Lieutenant General Lewis Brereton was one of the first to sign up for what would eventually become the U.S. Air Force. As a pioneer in the field of military flight, it was a big problem when he developed a fear of flying so bad that he had to consult a psychiatrist.

On February 22, 1927, Brereton requested sick leave, saying, "I have been under a nervous strain due to my conditions of living for a protracted time. ... The condition is adversely affecting my flying" (via Air Power History). Major Benjamin Warriner of the Medical Corps agreed that Brereton needed time off, saying that he was "suffering from an incipient anxiety neurosis of moderate degree characterized by a beginning fear of flying. ... Cause — domestic difficulties." Apparently, they all believed it was his estranged wife's fault.

While Brereton appeared to have gotten over his fear of flying by the time World War II began, he brought some additional odd behaviors to that conflict. Noted for having an almost photographic memory when it came to airplanes, and able to speak several languages, he was also notorious for forgetting his luggage when traveling during the war. When his suitcases did manage to get on a plane with him, they included a bulky typewriter — which he never used.

General Edmund Ironside

In hindsight, it is easy to forget that Nazi Germany could have won World War II, and that some Allied military leaders were sympathetic to or even supportive of the fascist cause. It's not known what British General Edmund Ironside's thoughts were, but he was good friends with the openly fascist Major General J. F. C. Fuller.

For whatever reason, Ironside did not make it a priority to end this relationship and even tried to help rehabilitate Fuller's military career. As recounted in a diary entry included in "Ironside: The Authorized Biography of Field Marshal Lord Ironside", he wrote of meeting Fuller for lunch to discuss a job: "Naturally, he was careful not to express his fascist feelings to me too strongly, because he wanted to know if he would be employed or not. ... Had he not been away playing so long with these Mosley Fascists he might have been invaluable."

Ironside was so fond of Fuller that it led to accusations that the general was part of a fascist plot to overthrow the English government. A since-declassified report includes information relayed by undercover MI5 agents about Ironside. Once the coup began, the plan was that "Italy would declare war almost immediately, that France would then give in, and that Britain would follow before the end of the week. ... General Ironside would become dictator and after things had settled down, Germany could do as she liked with Britain" (via the Berkeley Center for Right-Wing Studies).

General Dwight D. Eisenhower

While he is often ranked as one of the best military commanders in human history, it's possible that General Dwight D. Eisenhower would be more interested in where he ranks on a list of historical bridge players. The future president was a massive fan of the then-popular card game.

Eisenhower was such a serious and competitive bridge player that even in the midst of the most intense days of the war, he made personnel decisions at least partly based on someone's talent at the card table. When it came to selecting his naval aide, the general's right-hand man, he chose skilled bridge player Captain Harry Butcher. Nor was this a one-off; after the war, he selected as his second-in-command at NATO a man known to be the best bridge player in the U.S. Army, who had won the "Bridge Battle of the Century" in 1931. "I ought to take [former Chief of Staff] Bedell Smith, but I think I'll take [General Alfred] Gruenther because he's the better bridge player," Eisenhower said (via NATO).

This obsession continued during his time in the White House, where the president often hosted games. According to the American Contract Bridge League, famous bridge player Ely Culbertson said, "You can always judge a man's character by the way he plays cards. Eisenhower is a calm and collected player and never whines at his losses. He is brilliant in victory but never commits the bridge player's worst crime of gloating when he wins."

General Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke

General Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke (pictured right) was leading the German defense of Brest in France in August 1944. Opposing him were U.S. forces led by Major General Troy Middleton (pictured left). During the weeks-long battle, the adversaries corresponded constantly, to the point that it was somewhat unusual. On September 12, 1944, Middleton wrote a seven-paragraph letter to his adversary, laying out all the reasons the Nazis should surrender. He said, in part, "Your men have fought well ... it is the consensus of all that you and your command have fulfilled the obligation to your country. ... I am calling upon you, as one professional soldier to another, to cease the struggle now in progress" (via Frank James Price's "Troy H. Middleton: A Biography"). His normally effusive pen pal replied with a single line: "General: I must decline your proposal."

Despite this mic drop, Ramcke was soon captured; he was discovered in a bunker with his dog, his mistress, 20 military uniforms, a full dinner service, and tons of alcohol. His official surrender (pictured) was just as surreal. Ramcke brought his dog and happily posed for photos as Middleton directed him where to stand. According to a reporter covering the event, at one point, Ramcke said, in English, "I feel like a film star."

After his capture, Ramcke spent some time in one of America's World War II German POW camps. He also continued writing to his old nemesis, Middleton: the two generals would continue to correspond regularly for the next 15 years.

General Archibald Wavell

There is nothing strange about men, even military men, being in touch with their more feminine or literary sides. Still, it is quite surprising that General Archibald Wavell was not only so obsessed with poetry that he collected and edited an anthology of it, but that he did so while serving on active duty in the middle of World War II. The general (later field marshal) was a huge fan of poetry, although he was too shy to recite it unless he was alone.

In the middle of the war, while stationed in Burma, Wavell put together a manuscript of 200 classic poems he knew by heart, along with his notes about them, and sent it to a publisher. Unfortunately, while the general might have loved poetry, he wasn't well-educated in it, so the literary world was far from impressed. The editor who saw his submission wrote a scathing reply, noting that the selections were far too old-school and that (since Wavell had written down the poems from memory) many of the poems had inaccuracies. Fortunately, another editor saw the potential and "Other Men's Flowers" was published in 1944. The book was a massive bestseller.

The poet T.S. Elliot later said of the general, "I do not pretend to be a judge of Wavell as a soldier ... What I do know from personal acquaintance with the man, is that he was a great man. This is not a term I use easily ..." (via The Guardian).

General Nathan Twining

When it comes to the weirdness surrounding General Nathan Twining (pictured far right), he really could not have seen it coming. In fact, he was doing something necessary and logical under the circumstances, but because of it, in the ensuing years, Twining's name would be inextricably linked with UFO conspiracy theories.

After serving in World War II, Twining went on to have an even more illustrious career, serving as chief of staff of the United States Air Force from 1953 to 1957, and as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1957 to 1960. But it was as head of the Air Force Technical Service Command that the general would make his contribution to the conspiracy world. On September 23, 1947, he signed his name to a top-secret memo entitled "AMC Opinion Concerning 'Flying Discs,'" which said that UFOs that Air Force pilots sometimes reported interacting with were real and should be studied. The memo stated, "It is the opinion that the phenomenon reported is something real and not visionary or fictitious" (via WPRI 12). This led to the establishment of Project SAUCER in 1948, which was quickly renamed Project SIGN, before changing again to Project GRUDGE, and finally into the infamous Project BLUE BOOK in 1952.

While Twining didn't mean the crafts were from outer space, this memo and the resulting project he headed up would hand ufologists all the evidence they needed that the government was covering up the existence of aliens, and the Twining memo became notorious.

General Hap Arnold

Aviation pioneer General Henry "Hap" Arnold was an affable-looking man. He always had a half-smile on his face, although this was not due to a positive outlook on life. The perpetual grin was the result of an issue similar to Bell's palsy, and anyone who misinterpreted what it meant was in for a world of hurt, because, in reality, Arnold was a ball of rage who had been lashing out uncontrollably at those around him since he was a cadet at West Point. "Hap," short for happy, was the most ironic nickname of all time.

Arnold would pick a fight with anyone, no matter their rank. His hair-trigger temper was legendary, and he was said to have no sense of humor. He constantly micromanaged his staff and had huge expectations, leading to him receiving a second nickname: "Do-it-yesterday Arnold."

Perhaps it is not surprising that a man who was basically an angry time bomb waiting to go off had suffered five heart attacks by the end of World War II. (Not that dedication to his job helped with the stress: Arnold remains the only airman to this day who became a five-star general.) He retired in 1946 in an attempt to relax. Despite his aggressive and abusive manner, it seems those who worked with the general came to terms with his personality. According to HistoryNet, one staff officer who knew what it was to be screamed at by Arnold allegedly said, "How can you hate a guy who's always smiling at you?"

General Hoyt Vandenberg

You would be forgiven for thinking that the attractive gentleman in the above image was not a soldier but rather a Hollywood leading man, cast in the role of a general for a World War II epic. However, that is actually General Hoyt Vandenberg, and while most military men are not remembered for their appearance, Vandenberg was so remarkably handsome that no one could stop talking about it at the time (or since).

Allegedly once called "the most impossibly handsome man on the entire Washington scene" by The Washington Post (via "Makers of the United States Air Force"), secretaries at the Pentagon would lean out of their offices to watch the general walk by. One aide saw Vandenberg attending a congressional baseball game and commented, "You never saw such pulchritude (beauty)! The women were falling all over themselves trying to get a look at [him]!" (via "Hoyt S. Vandenberg: The Life of a General"). It's even said that when asked which three men she would want to be stranded on a desert island with, Marilyn Monroe chose her husband Joe DiMaggio, Albert Einstein, and the gorgeous General Hoyt Vandenberg. The general graced the covers of several magazines over the years, including Life.

His attractiveness seems to have both positively and negatively affected Vandenberg's military career at different times. While looking the part may have contributed to his exceptionally rapid rise in the military, some saw him as just a dumb pretty boy coasting on his looks.

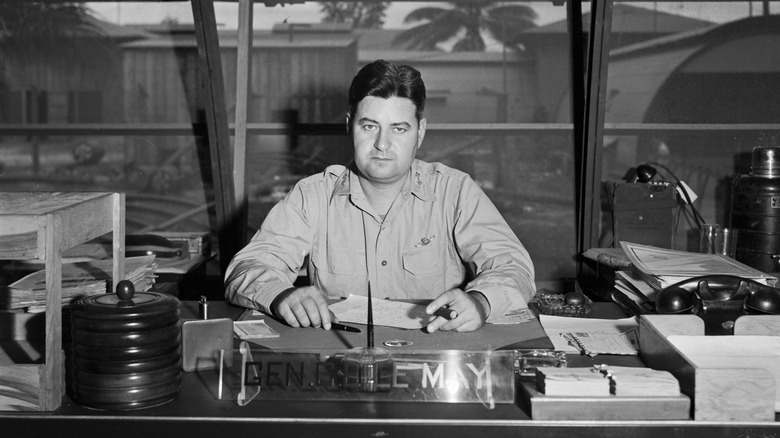

Major General Curtis LeMay

General Douglas MacArthur was famously relieved of his command in the middle of the Korean War, at least in part because he was very insistent about his desire to drop nuclear bombs on the country. However, as crazy as that possibility seems now, it doesn't hold a candle to the image that Major General Curtis LeMay was building for himself during the same period. After serving in World War II, LeMay became so famous for his gruff manner and paranoia during the Cold War that he was the inspiration for the unhinged General Jack Ripper in the classic black comedy satire "Dr. Strangelove."

As leader of the Strategic Air Command, LeMay was obsessed with the idea that the United States would be attacked. He once told a visiting businessman, "If I see that the Russians are amassing their planes for an attack, I'm going to knock the s*** out of them before they take off the ground." When the shocked man pointed out that was the opposite of U.S. policy, LeMay replied, "I don't care. It's my policy. That's what I'm going to do." (According to "Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb," another witness said LeMay's reply was actually, "It's my job to make it possible for the President to change his policy.")

Some felt that LeMay's openly aggressive attitude was part of an attempt to get the Soviet Union to start a full-scale war with the U.S.

Major General Charles Gerhardt

Major General Charles Gerhardt (center of the front group) came to the U.K. to train U.S. troops there prior to the Normandy invasion. In the U.K., his soldiers quickly learned he was a bit quirky. While they appreciated his unexpected decision to give them three days of leave, they were less impressed by his habit of dropping grenades on them from a plane while they practiced maneuvers. And locals were terrified of the trigger-happy general, who would pull out his sidearm and start shooting rabbits at any moment, even when in a moving car.

Gerhardt was what soldiers refer to as a "martinet," an angry officer who fixates on the smallest mistakes and makes troops suffer for them. He insisted on soldiers keeping the uncomfortable chin strap on their helmets buckled at all times. He himself wore cavalry boots shined to within an inch of their life and a fetching neckerchief. And Gerhardt's cooks were often sent scrambling to fulfill any strange craving he had.

The general was best known for his obsession with cleanliness, especially when it came to trucks and Jeeps. Gerhardt would order troops to stop whatever they were doing and clean the dirt off their trucks. Perhaps the most shocking example of the general being a fastidious taskmaster was when he yelled at a soldier for dropping the peel from an orange he was eating onto the beach at Normandy ... the day after D-Day, while surrounded by the still-smoking remnants of the battle.

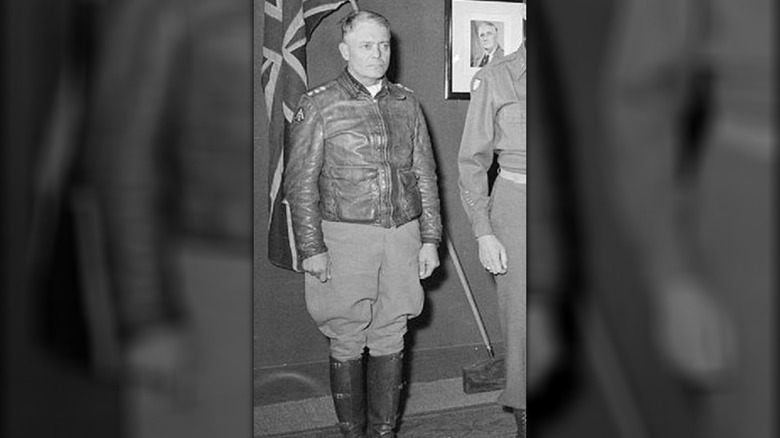

General Lucian Truscott

In war, there is no guarantee you will survive the next time you charge at an enemy under heavy fire, so it is understandable that some soldiers become superstitious. If you survived one battle, doing things the same way the next time might mean you get out of that one alive, too. For General Lucian Truscott, this meant making sure he was always wearing his "lucky" clothing.

It would be one thing if Truscott's lucky outfit were just a standard issue uniform, but it was not. As seen above, Truscott always wore an old pair of breeches and cavalry boots, along with a leather jacket. He also made a new white scarf for each battle with an escape map drawn on it in case things went wrong.

You might think that Truscott's clothing could not have had any real effect on his success in the war, but when he was injured by a shell shortly after the D-Day landings, his thick boots helped save him from a far worse injury than the one he sustained. The soldiers under Truscott embraced the suspicion just as much as he did, and many started wearing their own scarves in battle. During the Italy campaign, Truscott was injured in a Jeep accident; as a result of injuries to his legs, he was unable to put on his boots. Soldiers came to his hospital bed to beg him to keep trying, as they needed him to be wearing them during the next offensive, even if Truscott wouldn't be part of it, for luck.