Scandals That Destroyed These Reporters' Careers

Stripped of the trappings of personal, political, or corporate bias, journalism is a noble profession. Writers apply their reporting and storytelling skills in a never-ending pursuit of the truth. It's a scary reality being a journalist, as they really only have one tough job: Find the facts and share them with the world. It's a service to the public, and it connects communities and holds leaders accountable.

Journalism has simple core tenets, but sometimes those truth-seeking authors and interpreters of world events and nonfiction stories fail to do what they need to do. For whatever reason they found compelling at the time, many journalists have stolen the work of others and passed it off as their own, failed to maintain composure or balance, or straight up lied in what they presented and published as factual material. They usually get caught, and after a public denouncement, they're largely barred from their profession forever. Here are some once high-profile journalists who became the story when they scandalously violated all kinds of ethical standards.

Janet Cooke

After working as a reporter for the Toledo Blade, Janet Cooke landed a job at the Washington Post in early 1980. That fall, she published a lengthy and harrowing feature story called "Jimmy's World." Ostensibly about the crime and drug problems purportedly raging through inner Washington, D.C. at the time, the story was also a profile on an 8-year-old boy. Identified only as Jimmy, he was living amongst many daily dangers and hopelessly addicted to heroin. The piece became a local sensation, and D.C. Mayor Marion Barry and city officials all vowed to find Jimmy, give him the help he needs, and arrest his horrible parents.

In April 1981, Cooke won a Pulitzer Prize for "Jimmy's World." At this point, the Post's ethics officer noticed that the bio the author sent to the Pulitzer committee differed from the one she'd given her employer. That cast doubt on the legitimacy of Cooke's work, and questions had already been raised after no one in the D.C. government had been able to find Jimmy. Cooke finally confessed: She'd made the whole thing up, and Jimmy wasn't real. It was based somewhat in fact: An employee at a hospital's drug treatment ward told her they'd seen an 8-year-old, and after pitching it to an editor, she was unable to find the individual. Cooke was fired, and no publication would hire such a high-profile fabricator. By the late 1980s, she'd moved back to the Midwest and worked at a succession of department stores.

Jack Kelley

Jack Kelley began filing stories for USA Today in 1993, rising to the rank of foreign correspondent. It's tough being a reporter in a war zone, and in 2001, his first-person description of a suicide bombing landed him on the Pulitzer Prize short list. A decade into his tenure at USA Today, it became clear that Kelley was a serial fabricator and fictionalizer.

In early 2004, after editors followed up on a lead that Kelley may have falsified some stories, the reporter confessed to taking unethical liberties with a translator and resigned. Nine writers and editors then examined 720 Kelley stories published over the previous decade and found mistruths and falsehoods in 100. Hotel and phone records proved he hadn't been in many of the places he'd said he traveled to. Evidence recovered from his company laptop indicated that he'd coerced quotes by writing up scripts for what he wanted said and then got his associates to say them. Kelley had never been embedded in a terrorist cell or a group hunting Osama Bin Laden, never saw a terrorist hatch a plan to attack the Sears Tower, and never explored a terrorist camp in Afghanistan.

"As an institution, we failed our readers by not recognizing Jack Kelley's problems," USA Today publisher Craig Moon wrote. "For that I apologize. In the future, we will make certain that an environment is created in which abuses will never again occur." Kelly retired to private life and has quietly volunteered with charitable organizations.

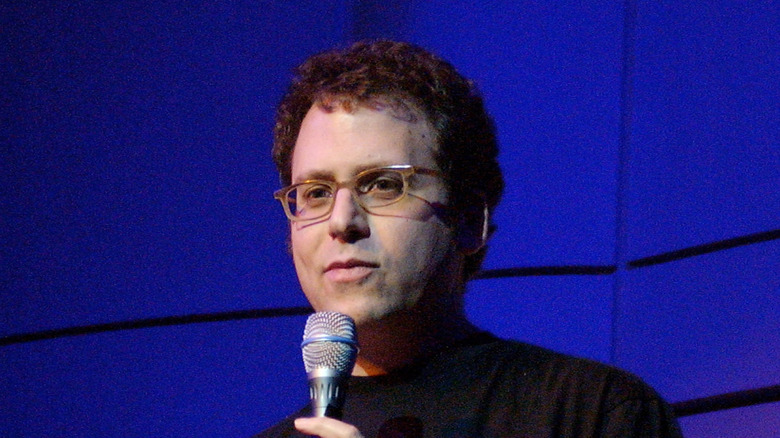

Mike Daisey

Mike Daisey is a monologist, meaning he delivers monologues about social and cultural issues. In January 2012, he performed a portion of his one-man show, "The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs," on public radio's highly rated and much downloaded show and podcast, "This American Life." Well over a million people experienced "Mister Daisey Goes to China," a segment in which Daisey, a self-professed enthusiast for Apple products, gets his thoughts out about visiting some factories in China. They were operated by electronics contractor FoxConn, where iPhones are manufactured. Daisey soon rethought and shed his Apple fandom, as he witnessed and then described to listeners the subhuman and degrading working conditions he saw at the FoxConn plant.

Apple was urged to act, and in covering that story, the public radio show "Marketplace" interviewed the interpreter Daisey had used on his factory visits — and they said Daisey stretched the truth quite a bit. Not only did he lie about how many factories and workers he talked to, but he also said he met the victims of a poisoning accident. That occurred, but not at a facility Daisey visited. And the climactic moment, where Daisey presented a finished iPad to a Chinese worker who had never even seen the fruit of his labors, was total fiction. "This American Life" issued a retraction of the story. Daisey continued to perform monologues, but not for "This American Life," and he focused on less controversial topics in smaller venues.

Terry Moran

One of ABC News' most accomplished journalists, Terry Moran co-anchored and reported for "Nightline." He also served as the organization's chief foreign correspondent while also covering domestic politics, including presidential elections and debates and Supreme Court rulings. Notably, Moran interviewed President Barack Obama nine times and sat down with President Donald Trump in 2025 ahead of big changes his presidency could bring. He generally kept an even hand and reported without revealing any of his personal biases or political preferences.

Then, in a June 2025 post on X, formerly known as Twitter, Moran let his distaste for the Trump administration be known, calling deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller (via the New York Times) "a man who is richly endowed with the capacity for hatred" and the president "a world-class hater." Moran quickly deleted his postings, but they'd already been widely viewed. Vice president and horrific childhood survivor J.D. Vance asked for an apology from ABC News for what he deemed on X to be "an absolutely vile smear." Within a day, ABC News moved to suspend Moran indefinitely, and days later, the reporter's employer of 28 years fired him outright. "I was thinking about our country, and what's happening, and just turned it over in my mind," Moran told the New York Times.

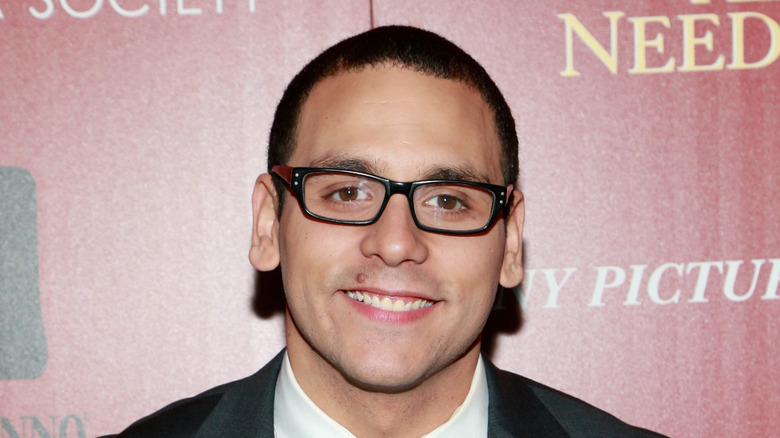

Jayson Blair

Jayson Blair interned at the New York Times and was hired on as a junior writer. He wrote prodigiously, turning in 600 articles in about four years' time. In October 2002, he was named a staff reporter on the national news desk, despite almost getting fired earlier that year for sloppy work. Just seven months later, with discrepancies appearing in his work, Blair resigned his position. In one of the biggest controversies to ever hit the New York Times, a staff investigation found that half of the articles he wrote as a staff reporter contained something untruthful.

Blair claimed to have traveled to Maryland, Texas, and Virginia to write, research, and gather interviews for stories about the effects of the Iraq War on military families and the Washington D.C. Beltway sniper case. But he hadn't left New York at all. Using details he spotted in news photographs of his subjects, he convincingly made his reporting seem real. Blair was also found to have invented or doctored quotes and taken passages from other publications and wire services and turned them in as his own work. When they went back to look at his early stories, Times staff found falsehoods in those pieces, too. About a year after he was ousted, Blair wrote "Burning Down My Masters' House," a memoir about his Times years and his bipolar disorder diagnosis. He later created the Depression Bipolar Alliance of Northern Virginia and became a mental health and life coach.

Ruth Shalit Barrett

By age 24, Ruth Shalit had worked for several of the country's most prestigious news outlets and had been named an associate editor at The New Republic. In 1994, the publication discovered that her story about youthful politicos in the administration of President Bill Clinton contained lengthy passages lifted from a Legal Times article. Then parts of a National Journal profile on presidential candidate Steve Forbes appeared unchanged in another Shalit piece. Shalit claimed that she'd accidentally plagiarized twice because she'd mistakenly published her notes instead of the completed articles. After more accusations of plagiarism and quote embellishment, Shalit exited The New Republic in 1999 and worked for a New York advertising agency but managed to publish again, albeit under her married name of Ruth Shalit Barrett.

More than two decades removed from scandal, Barrett landed a piece on the link between obscure high school sports and Ivy League college admissions in a late 2020 issue of The Atlantic. The publication soon had to post an explanation on the digital version of the story, telling readers that the piece could be misleading. One source Barrett interviewed, a parent who went by Sloane, turned out to not have a son at all. "Sloane" claimed that Barrett had come up with the idea to go along with the falsehood. The Atlantic cut ties with Barrett, who then sued the magazine, claiming that outing the phony details in her work "destroyed her reputation and career," per The Washington Post.

Benny Johnson

Benny Johnson served as the viral politics editor for BuzzFeed in the 2010s. In July 2014, users on X, formerly known as Twitter, started posting samples of Johnson's work at BuzzFeed that closely resembled previously published works composed by other authors. J.K. Trotter of Gawker dug deeper and found that many of Johnson's articles had used phrases, sentences, and chunks of content from other publications without any credit. Johnson's most common sources: Wikipedia, Yahoo! Answers, the New York Times, and U.S. News and World Report.

BuzzFeed's editorial board quietly launched an internal investigation, and after examining 500 pieces written by Johnson, the team discovered that 41 articles, published from January 2013 to June 2014, had been plagiarized in some way. BuzzFeed staff rewrote all 41 articles so they were comprised of 100% original reporting, and editor Ben Smith issued a public apology. "This plagiarism is a breach of our fundamental responsibility to be honest with you," he wrote. "We will work hard to be more vigilant in the future, and to earn your trust."

BuzzFeed immediately fired Johnson, who apologized on X, formerly known as Twitter. "To the writers who were not properly attributed and anyone who ever read my byline, I am sincerely sorry," he wrote. Johnson went on to become an independent online journalist unaffiliated with any major news organization and a political podcaster.

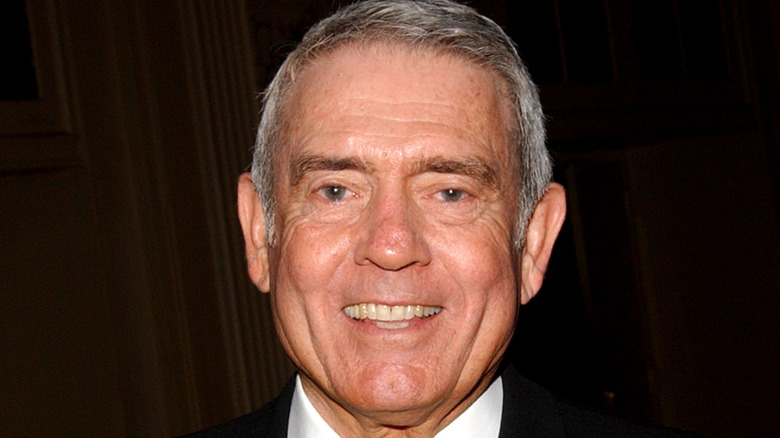

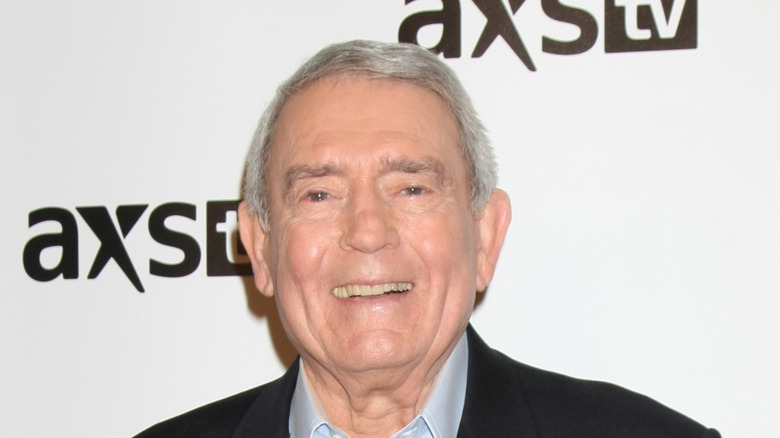

Dan Rather

In the pre-cable and pre-internet world, Dan Rather was one of three evening network anchors and thus one of the most influential figures in television news. Succeeding the beloved Walter Cronkite in 1980, Rather starred on and helped run "CBS Evening News" for decades. He dutifully delivered the news while also investigating and reporting his findings, including a bombshell 2004 story on President George W. Bush, who at the time was up for reelection. Other news entities had looked into the commander-in-chief's term of service in the Texas Air National Guard in the 1970s and if he'd landed a plum and privileged assignment because he was from a powerful and wealthy family. But Rather evidently blew the story open. He and producer Mary Mapes discovered documents allegedly generated by Bush's commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Killian. They indicated that the future president didn't have to endure a medical check and enjoyed glowing evaluations he didn't necessarily earn.

After Rather shared his findings on CBS News programs, watchdogs called the Killian documents into question. They suggested the information had been faked on account of how a character looked like it was generated by a modern computer, not a typewriter. At first, CBS stood by Rather and his work, but after it became clear that the documents couldn't be verified, it ordered him to kill the story. Mapes was fired, and on March 9, 2005, Rather appeared on his final broadcast of the "CBS Evening News."

Stephen Glass

Fresh out of college in 1995, Stephen Glass got a job as an editorial assistant at The New Republic, and soon he became an associate editor. He built a following for his crackling, richly woven stories populated by highly realized characterizations of his subjects. One such article in that style was a May 1998 piece, "Hack Heaven," in which Glass profiled 15-year-old computer hacker Ian Restil. Restil had allegedly been hired as a security consultant by Jukt Micronics after he'd remotely breached its network and extorted its executives and also attended a convention held by the National Assembly of Hackers.

Forbes Digital Tool reporter Adam Penenberg pitched a follow-up on Restil but found that he couldn't verify a single thing mentioned in Glass' piece. Instead, Penenberg wrote an exposé, and his publication alerted The New Republic lead editor Charles Lane. Previously accused by outside, profiled parties of inventing material for his stories (accusations that were dismissed by the magazine), Lane discovered that Glass made up pretty much everything in "Hack Heaven" and had also concocted fake evidence to bolster his lies. Restil didn't exist, and neither did Jukt Micronics or the National Assembly of Hackers — although Glass built a website for the former and printed a newsletter for the latter. A look at Glass' other stories revealed similar creative liberties. The journalist was fired, and after attending law school and passing the bar, he worked in a low-level position at a firm specializing in injury cases.

A.J. Clemente

On April 21, 2013, Bismarck, North Dakota NBC affiliate KFYR began its live broadcast of the Sunday night edition of its flagship newscast, "Evening Report." It marked the debut of the station's newest anchor hire, the just-graduated A.J. Clemente. Nerves likely played a factor in Clemente monumentally bungling the story, committing a couple of unforced errors that generated a historically terrible news blooper that actually happened on-air. After Clemente tentatively read off of a script to tease a couple of stories the program was about to cover, the announcer took over to introduce the show. Immediately thereafter, and with his microphone live, the first-day anchor muttered, "Gee, f****** s***," and kept mumbling as his cohort Van Tieu spoke, attempting to introduce the visibly frightened Clemente. When given the chance to speak again, he garbled his words, but at least he didn't swear. "Thanks, Van, I'm very excited," he managed. "I graduated from West Virginia University, and I'm used to, um, you know, from being from the East Coast."

After turning out what is probably the worst and most profanity-addled first broadcast performance in TV news history, Clemente was fired by KFYR within hours. "Rookie mistake. I'm a free agent," he announced on X, formerly known as Twitter. "Can't help but laugh at myself and stay positive." After his unfortunate viral moment, Clemente never worked in news media again and went on to become a bartender in Delaware.