How WWII Could Have Been Even Worse

It is chilling to imagine World War II being even worse than it actually was. Few events in history resulted in the deaths of more people than that global conflict: An estimated 45 to 60 million people died, both military and civilians. And while the battles were bloody, the millions of Jewish people and others from minority groups who died in the Holocaust brought the horrors of the war to another level.

So the idea of things going even worse is difficult to contemplate. But war is complicated and messy, which means there are any number of junctures where, had things gone a little bit differently, the outcome could have been disastrous. Add just a few of those "sliding doors" moments up over the course of the conflict and you could be looking at millions more deaths, the war dragging on for years longer, or, most disastrous of all, the Axis powers emerging victorious from the conflict.

Some of these events came within a hair's breadth of disaster, while others were always unlikely to happen. Yet they all could have changed the course of world history if things had gone a little differently. Here are just some of the ways that World War II could have been even worse.

The Kyūjō incident

After Germany surrendered to the Allies on May 8, 1945 — V-E Day — Japan was the last of the three Axis powers standing. Italy had surrendered way back in 1943, and there was no guarantee that Japan would ever do the same. After all, this was the same country that resorted to kamikaze attacks in desperation. The nation where soldiers and even civilians sometimes died by suicide rather than surrender to the Allied troops island-hopping across the Pacific.

The United States had plans if Japan hadn't surrendered in World War II, including even more firebombing campaigns and a possible full-scale invasion, which would have cost innumerable more lives. There was also the possibility that the already hungry Japanese population would starve if the war continued. After the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Emperor Hirohito knew his country needed to surrender. But not everyone in the government agreed with him, even after a second nuclear attack on Nagasaki.

In a last-ditch attempt to keep Japan from surrendering, members of the government and the Imperial Guard tried to foment a coup and stop the emperor's plan. On the night of August 14, 1945, Kenji Hatanaka and Jiro Shiizaki led other rebels to the Imperial Palace, where they successfully took control of the compound. Thankfully, the Kyūjō incident failed because the rebels were unable to locate the emperor or the declaration of surrender, and no military leaders agreed to support their attempt to keep Japan in the war.

More destruction at Pearl Harbor

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt stood in front of Congress and called December 7, 1941 "a date which will live in infamy," he was not exaggerating how terrible the Pearl Harbor attack was for the United States. The Japanese took the Hawaiian military base completely by surprise, and the losses were devastating. A total of 2,403 Americans died, including 68 civilians, with more than a thousand additional military members and civilians suffering injuries. Eight battleships were lost or damaged, as well as seven other ships and almost 200 planes.

Despite the staggering tragedy, it could have been much worse. While a successful sneak attack in many respects, the destruction at Pearl Harbor barely put a dent in the United States' Pacific fleet. The Japanese pilots only hit 18 out of 96 ships (15 were repaired and later used in the war), and all three aircraft carriers just happened to be out at sea at the time. There are plenty of things about the Pearl Harbor attack that don't make sense, but one of the weirdest things is that the U.S. was actually very lucky that it was a complete surprise. Had they expected an attack to happen at any moment, there is no way the Navy would have left Pearl Harbor undefended by its aircraft carriers. However, with Japan countering with a force of six carriers, the outnumbered U.S. could have lost anywhere from 33 to 100% of its most vital ships in the coming war.

The success of Operation K

Because the attack on Pearl Harbor was not a complete success for the Japanese due to the most important ships not being in port at the time, plans were quickly drawn up for a second attack on the military base. The code name for a second planned mission was "Operation K," and it was to take place several months after the first. This follow-up was never meant to do the kind of destruction the original did — it was meant to cause additional damage, disrupt repair work at the base, and damage morale.

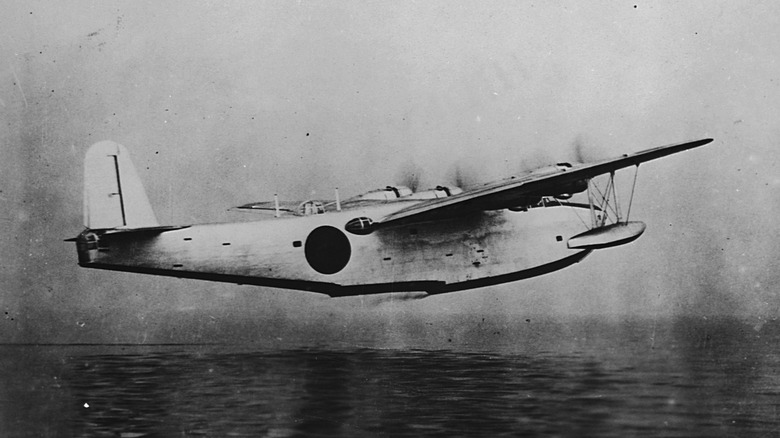

The plan was for five long-range Kawanishi H8K planes (pictured) to drop four 550-pound bombs on the base. But the flights would also gather reconnaissance information on how quickly repairs from the original attack, which was almost even more important. The Japanese needed to know when the U.S. Navy in the Pacific would be back up to full strength. Luckily for the U.S. war effort, when the conditions were right for the attack on March 4, 1942, only two of the planned five Japanese planes were available.

In a record-breaking flight, the aircraft flew over 2,000 miles round-trip from the Marshall Islands to Hawaii. More went wrong along the way. Not only were the planes detected by U.S. forces, but thick cloud cover also resulted in them being separated and unable to properly aim the bombs. In the end, the explosives fell into the ocean and near a school. They caused little damage and no casualties.

Spain joining the Axis

On paper, Spanish dictator Francisco Franco would have been the perfect ally for Adolf Hitler during World War II. They were both dictators of fascist governments, and Franco was open about his Nazi sympathies. German and Italian troops had even assisted in Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War. Despite all this, Spain stayed neutral during World War II. Had the country ever decided to join the fight on the side of the Axis, Hitler would have been ready with plans that would have been disastrous for the Allies.

Perhaps the biggest concern would be Franco's demand for Gibraltar. Britain had conquered the "Rock" off the coast of Southern Spain in 1713, and Spain wanted it back. If Hitler had been forced to commit to taking Gibraltar in order to get Franco to enter the war, and had he succeeded in invading the island, the Allies would have lost access to the Mediterranean, as well as a key location for planning and launching military campaigns in North Africa.

Gibraltar was not the only piece of land Franco wanted in exchange for officially joining the war on Hitler's side. Fortunately for the Allies, the two dictators were never able to come to an agreement on terms, despite serious attempts to come to a deal almost all the way up to 1943. But while Franco provided support to the side he wanted to win through trade and propaganda, he never committed Spanish troops to the war.

Operation Sea Lion

Following the Fall of France, the Battle of Dunkirk marked the tragic culmination of a devastating period for the Allies early in World War II. Pretty much the only good thing for the Allies was that Hitler made a critical mistake in the Battle of Dunkirk: He delayed sending in the tanks that would have wiped out the Allied forces. Instead, they had several days to mount a massive evacuation by sea to Britain.

Hitler had driven the opposing forces out of mainland Europe, but he had also failed to destroy them so completely that an Allied surrender would be conceivable. With this in mind, he began planning for his next logical step: invading England. Had the Germans successfully invaded the island, World War II would have been a completely different story. After being forced out of Continental Europe, Britain became the epicenter of planning and organizing the D-Day landings, and it was the only location the Allies controlled that would have allowed for a successful invasion of France.

Hitler began massing ships at ports in Northern France (pictured). The Luftwaffe was tasked with destroying the Royal Air Force so German ships could safely cross the English Channel. However, they never managed to do this. The invasion of England, which Hitler originally wanted completed by August 10, 1940, kept being pushed back as the Nazis waited for the conditions to improve. While Hitler never officially canceled Operation Sealion, the perfect conditions never materialized before Germany's defeat.

A German atomic bomb

The United States wasn't the only country racing to crack the physics necessary to harness the power of the atom into a destructive force unlike anything the world had ever seen. Indeed, the "what ifs" of an alternate scenario where the Nazis succeeded in getting a nuke send shivers down the spines of historians. While it turned out the Nazis were nowhere near successfully cracking the problem of nuclear weapons, the Allies knew they were trying to. We even have the mysterious cube that the Nazis may have used when they tried to build an atomic bomb. And while some of the most brilliant scientific minds in the world were German, many of them — including Albert Einstein and Erwin Schrodinger — had fled the country after Adolf Hitler's rise to power. While the Nazis still had Werner Heisenberg (pictured), the Allies had the upper hand in terms of physicists on their side.

If the Nazis had overcome other problems they faced — including a lack of sufficient money and resources — and built the bomb, there is no way of knowing what Hitler would have done with the superweapon. It is possible he might have chosen not to use it, or even that using it would not have been as effective on a huge country like the Soviet Union as the nuclear bombs were on an already beleaguered Japan. It is just as likely that he could have used them strategically and won the war.

The Axis capturing the Suez Canal

When Italy invaded Egypt on September 13, 1940, it was clear what their ultimate objective was: Take control of the Suez Canal. The waterway was vital for shipping, and since 1936, it had been guarded by British troops — troops who were now desperately outnumbered. Had German troops shown up to support their Italian allies, there is a very good chance they would have succeeded in controlling the canal.

Hitler knew this, and he offered the necessary troops — it was Benito Mussolini who refused the help. It turned out that the dictators were a bit at odds at that time, with Mussolini upset that Hitler had rejected Italy's offer to assist in the Battle of Britain. Mussolini believed that taking the Suez Canal without German support would restore Italy's pride.

This was extremely lucky for the Allies. The Nazi forces would have been a far more formidable opponent. After the war, German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring said of the Italian troops (via Warfare History), "They seemed to have a garrison mentality, and, in fact, much of their training was done in garrison—a totally inappropriate practice for exposing troops to the hardships of the battlefield. Their training remained superficial, without having reached a satisfactory level. The Italian soldier was not a soldier from within. The Italian soldier cannot be compared to the German soldier." While obviously biased himself, his opinion was shared by most observers, and the Italians failed to capture the canal.

Operation Pastorius

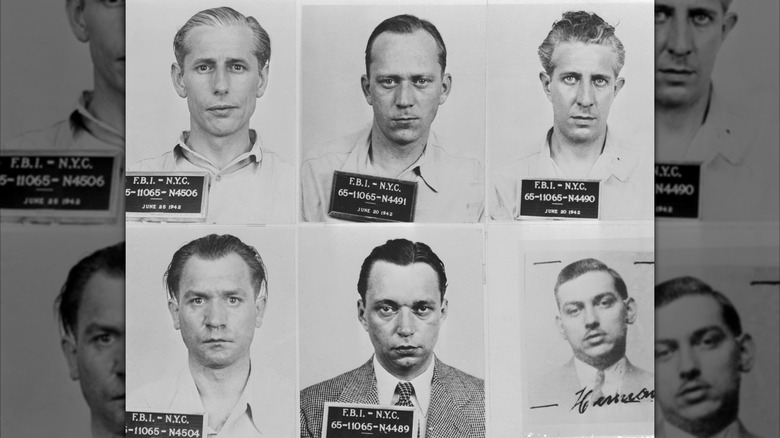

On June 13 and June 17, 1942, eight Nazi saboteurs were smuggled into the U.S. with explosives and tens of thousands of dollars in cash. They had a detailed plan to spend the next two years blowing things up, with the goal of hindering military production, creating panic, and lowering morale in America, which had only entered the war about seven months before. There was every chance the Nazi saboteurs would succeed, as they were well-financed and well-prepared. After 18 days at a special training camp in Germany where they learned the finer points of terrorism, two groups of four saboteurs each landed in Florida and Long Island.

All eight men had previously lived in the U.S., but they were not experts in this kind of warfare. For the New York group, things immediately went wrong. George John Dasch almost drowned getting from the U-boat to the shore. While lying on the sand recovering, he was discovered by a member of the coastguard. For some baffling reason, the saboteurs landed wearing their Nazi uniforms. Dasch attempted to bribe the man, who subsequently reported the incident to the FBI. Dasch made it easier for law enforcement by turning himself in and spilling everything.

The World War II German saboteurs who tried to blow up America faced serious consequences. Six were executed by electric chair on August 8, 1942. Dasch was originally sentenced to death, but this was commuted to a 30-year sentence, while the eighth conspirator's death sentence was commuted to life in prison.

Either side could have used chemical weapons

While World War II resulted in the deaths of many more people, certain aspects of World War I were arguably more horrific. No matter how bad you already think it was, World War I was worse than you thought. One of the main reasons? The poison gas that was regularly used on the battlefield not only caused unbelievably painful deaths, but it also left surviving soldiers with injuries, including scarring and blindness.

The Axis and the Allied countries both had access to stocks of chemical weapons a quarter of a century later, and it is easy to see a scenario where the leaders of one or both sides could have gotten desperate enough to use them. The Germans, in particular, had extremely deadly stores of sarin and mustard gas.

We may never know why neither side, but especially the Germans, resorted to using gas, but there are theories. It may be that since Adolf Hitler and Franklin Roosevelt were still traumatized by the effects of poison gas on World War I soldiers, they chose not to use chemical weapons on the battlefield during World War II. The Axis and the Allies were equally concerned that if they made the first move and used chemical warfare on the battlefield, the other side would respond in kind.

The Nazis could have figured out the location of D-Day

After the Fall of France, it was clear that defeating the Axis would be impossible unless the Allied troops managed to regain a foothold on the continent of Europe. This meant there was no great mystery about what they would eventually do. Adolph Hitler knew the Allies would attempt an amphibious assault somewhere in Western Europe — the question was where?

The Allies knew that maintaining the secrecy of their plan was vital. If Hitler had predicted where they would invade, he would have made sure to build up the German military presence in that area, meaning D-Day's chance of success would have been seriously hampered. General Dwight Eisenhower was aware of the chances of failure, even if the attack was largely a surprise, and wrote a statement taking responsibility for the failure of D-Day, should the worst happen.

To keep the Führer guessing, the Allied powers went to huge lengths to make it look like they were planning to land somewhere else, like Pas-de-Calais. Despite many complicated deceptions, some of Hitler's underlings still managed to correctly predict that the Allied invasion would be at Normandy. Fortunately, Hitler disagreed, or the war could have ended much differently.