Directors Who Are Really Weird People

Throughout "The Joy of Painting," Bob Ross would encourage viewers who painted along with him to name the trees, bushes, and mountains in his landscapes and make friends with them, even invent stories about them. He even encouraged them to go outside and talk to the trees and plants in their yard. "People [will] look at you like you're a little weird," he cautioned with a laugh (via YouTube), "but just tell 'em you're an artist ... as artists, we're allowed to be a little different."

If not universally true — plenty of people take up arts and crafts without talking to trees — Ross' broader point that the arts are a haven for eccentrics has been the case throughout history. Whether it's painters who go about with flamboyant moustaches and pet ocelots or brilliant composers with scatological senses of humor, art history is packed with geniuses in all disciplines who had their share of quirks. It's no different in the modern era — consider all the great '80s musicians who were really weird people.

But what about the people at the helm of a more collaborative art — say, film directors? Cinema depends on a wide range of talents beyond the chief filmmaker, and some directors are reluctant to even consider it an art rather than a craft. Nevertheless, there are some who raise their films into undeniable art. And there are also directors who can be just as strange in private life as certain painters, composers, and musicians.

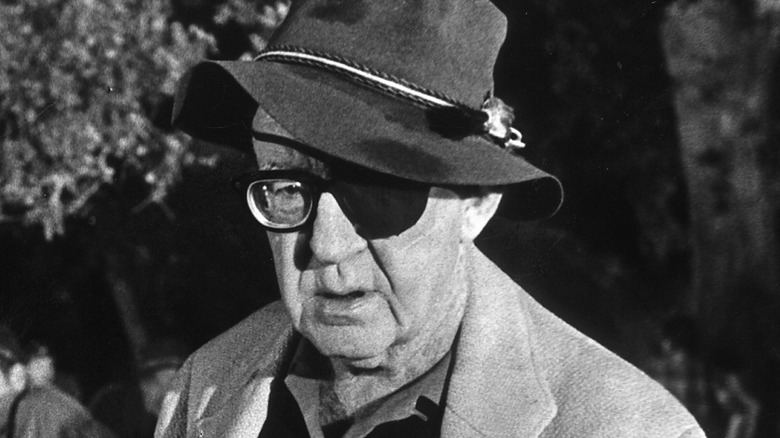

John Ford

When you look at John Ford, with his eyepatch, cap, and old jacket, you probably wouldn't think him an eccentric artist. Nor did Ford present himself as an artist or even as a person particularly emotional about his work. He put on a tough front for on-camera interviews, seemingly determined to give the most blunt, unromantic, and unrevealing answers possible.

But Ford once conceded in a BBC interview that "everybody has a little eccentricity in their character." Though he wouldn't consider his own quirks, there are a few undeniable examples in his working habits. It's rare, for instance, that directors insist on live music being played during filming or demand English-style tea breaks. And Ford was known for his handkerchiefs — specifically, how he'd chew them apart during takes, going through several a day.

Stranger than any habits, though, is why Ford felt his tough persona had to be maintained so strenuously. There was a massive disconnect between the director who belittled John Wayne mercilessly on set and the man who pensioned 22 families during the Great Depression (per Tag Gallagher's "John Ford: The Man and His Films"). Yet when a desperate old actor approached Ford for help paying for his wife's operation, Ford made a show of rage before storming off, leaving an aide to provide the requested funds. He always used intermediaries to do his charity and kept his beneficiaries from directly contacting him, lest they offer thanks he couldn't bear to hear. If they did, "people would realize what a softy Jack is," his brother Francis said. "He's built this whole legend of toughness around himself to protect his softness."

James Whale

English director James Whale's Hollywood career was unusual. At a time when the studio system assigned movies to directors and maintained the final cut, he was given virtual carte blanche by Universal Studios. The success of Whale's 1931 classic "Frankenstein" was so great that, as long as he turned in another horror film every once in a while, he could do as he pleased. Even on such later horrors as "The Invisible Man" and "Bride of Frankenstein," Whale had the unprecedented freedom to shape the projects to his stylish, subversive, and humorous liking.

That Whale could achieve such creative control under the studio system would be unusual enough. Stranger still was that he managed it as a gay man in an era of intense homophobia. Whale wasn't outspoken about his sexuality, but he did nothing to hide it either. It was unheard of then to be openly gay, particularly in his native Britain, where homosexuality was illegal.

Yet his lifestyle seems to have had no effect on his career in any sense. In response to more modern critics reading "Bride of Frankenstein" as a gay film, his friend, Curtis Harrington, told Films in Review: "I would bet my life that James Whale would never have had such concepts in mind. He was making a wonderfully amusing entertainment." With that said, though his sexuality never hurt his career, a regime change at Universal cost Whale his creative freedom, and he retired soon after. In his older years, he took to hosting all-male pool parties at his California home, despite the fact that he couldn't swim.

Tod Browning

Before James Whale's "Frankenstein," there was Tod Browning's "Dracula." Together, they launched the horror genre as we know it. But unlike Whale, who was at times ambivalent about his horror films and always sought other projects, Browning was comfortably ensconced in mystery and macabre thrillers. His heyday was in the silent era, where critics and studio publicity dubbed him "the Edgar Allan Poe of the screen." But Browning came by that association with classic Gothic literature in a roundabout way.

Born in Kentucky in 1880, Browning got his start in show business through the circus. He ran away from home at age 16 to join up and immediately took to the darker side of circus acts (he headlined as "The Living Corpse" in a live burial act). An encounter with D.W. Griffith led to work as an actor in Hollywood, followed by jobs as a writer and finally as a director. His career really took off with a long and fruitful collaboration with Lon Chaney, who had similar interests in the macabre. Browning's career was eventually derailed when his 1932 passion project "Freaks" proved too disturbing for contemporary audiences.

In his private life, which he kept well-guarded, Browning was no prince of darkness, but he had an unfortunate habit. Per David Skal's "Dark Carnival," both Browning and his wife were compulsive thieves. They made a habit of taking jewelry (jewel heists being a regular feature of Browning's stories), and Browning used his circus background to avoid paying full fare at the MGM commissary despite his lucrative career — and his pilfered gemstones.

Frank Capra

Frank Capra's most famous films can be thought of as Americana embodied in celluloid. "It Happened One Night," "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington," and "It's A Wonderful Life" have all been hailed for their charm, humor, and affirmation of American ideals. In the era of the Great Depression and World War II, such themes resonated strongly with an American public that overwhelmingly voted for Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his New Deal.

And yet Capra himself was no fan of FDR. One of the strangest things about the director is the intense contradiction between the themes in his work and his own politics. He was a lifelong Republican voter, a fierce anti-communist, and a proponent of loyalty oaths during the McCarthy era. Yet his career was helped enormously by screenwriters Capra knew were New Dealers and communists, a fact he tried to downplay later in life. Ironically, it was the villainous banker in "It's A Wonderful Life" that led the FBI to wonder if the film was wholesome entertainment or communist propaganda — something that cut Capra to the core. After all, he was self-conscious about his own rags-to-riches story and griped about the high taxes on the rich in his heyday.

Perhaps strangest of all is Capra's infatuation with Francisco Franco and Benito Mussolini in the 1930s. It may be that Capra, like many conservatives, considered fascism preferable to communism. Yet it's difficult to reconcile that attitude with a film like "Meet John Doe," which deals with a possible fascist takeover of the United States and comes down firmly on the side of American democracy.

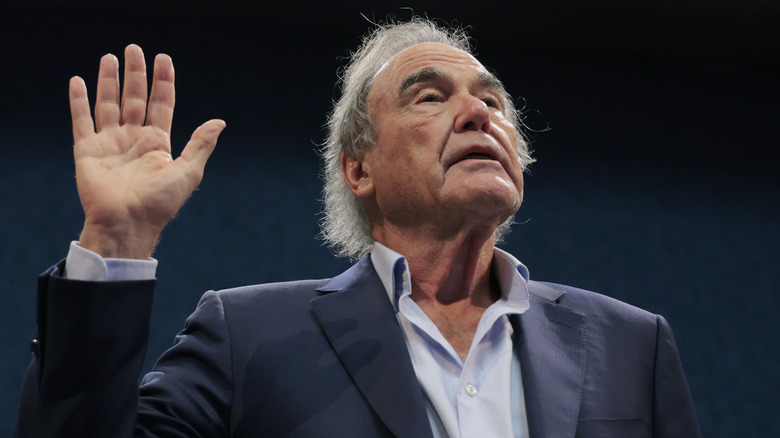

Oliver Stone

You don't have to be a conspiracy theorist to make movies about conspiracy theories or even take them that seriously (just ask the minds behind "National Treasure"). But in Oliver Stone's case, the two coincide. "JFK" remains one his greatest claims to fame, but its proposed conspiracy isn't exactly accurate or beloved by historians. Even Stone admits these days that its premise is based more on "vibes" than facts, though he's also called for new congressional investigations into the assassination as of 2025.

Possible plots against John F. Kennedy are hardly Stone's only indulgence in conspiracy theories. At an HBO Films panel in 2001, Stone left the audience and his fellow panelists shocked when he blended reasoned concerns about the corporate consolidation of media in America with the idea that the September 11 terrorist attacks were somehow connected to the 2000 presidential election. At the same time, he implied that the attack was in some way analogous to the French and Russian Revolutions.

Away from conspiracy theories, Stone has attracted controversy for his comments about dictators, past and present. He was criticized in the lead-up to his Showtime docuseries "The Secret History of America" (later renamed "The Untold History of the United States") for calling Adolf Hitler an "easy scapegoat," though he was referring to the need to put figures like Hitler in the context of events surrounding them (per Reuters). But Stone has unambiguously praised Hugo Chavez and conducted an interview with Vladimir Putin that was widely criticized for being deferential, even admiring.

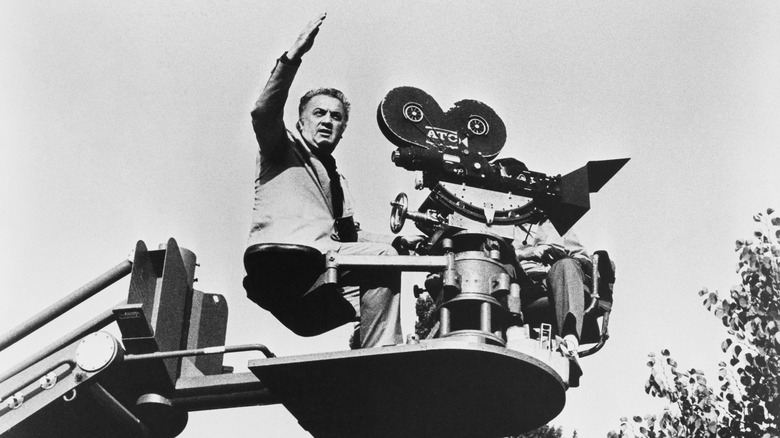

Federico Fellini

A lot of ink has been spilled over the ways a director's films reflect their personalities and obsessions. The auteur theory, as it's known, has its limits. Directors-for-hire tend not to be picky about subject matter, and one never knows how much producers and studios meddle in a movie's final composition. But there are cases where the theory holds true, and one of those cases is undoubtedly the work of Federico Fellini.

Moving from offbeat and surreal narratives to ostentatious exercises in mood and style, Fellini's work was so distinct that he inspired his own adjective. Critics have remarked, not always kindly, that Fellini's movies became increasingly about himself, his talent, and his own foibles. And Fellini's presentation of those themes may have been heavily influenced by an LSD trip in the summer of 1964 (per The Face).

That trip, supervised by Fellini's psychoanalyst as a new kind of therapy, was his only experience with LSD. But the experience had a profound impact on the director. "[It] was naturally a vision of Heaven and Hell ... and like all genuine visions, very difficult to express in words," he recounted later (via his own "I'm a Born Liar: A Fellini Lexicon"). He spoke about the incredible perception of colors he had under the influence, which some critics have tied into his use of color in later films, and attributed the short "Toby Dammit" as his closest representation of the experience. The connection between Fellini's trip and movies is intriguing enough to have a multi-author academic paper about it: "A phenomenological analysis of Fellini's films to understand the effect of LSD therapy on his creativity."

Michael Cimino

Few directors have followed the standard "rise and fall" success arc like Michael Cimino. After making "The Deer Hunter" in 1978, he became the toast of Hollywood, lauded and awarded and entrusted with millions of dollars and creative control over his next project, "Heaven's Gate." It was such a massive flop that it was blamed for ruining United Artists and has been blamed for ending the New Hollywood era of cinema.

Cimino's name went from brilliant to mud with the studios, and he struggled for the rest of his life to get projects off the ground. Frozen out of Hollywood creatively, he retreated more and more from it socially, until his own agent called him "the Howard Hughes of Hollywood" (per Vanity Fair). His closest friends weren't invited to his home, where he lived alone. Colleagues described meetings in darkened rooms with hushed voices and a cloth covering Cimino's face. And while denying rumors of substance abuse, Cimino, by his own admission, played fast and loose with his life story. "When I'm kidding, I'm serious, and when I'm serious, I'm kidding," he told Vanity Fair in a rare interview.

The interviewer commented on Cimino's radically altered appearance, which the director said came from weight loss and surgery on his jaw, though a friend blamed it on a car accident. His physical changes fueled longstanding rumors that Cimino was transgender, which he denied. But after his death, cosmetologist Valerie Driscoll claimed that she helped Cimino present as a woman named Nikki in the 1990s (per The New Yorker). But given how deceptive Cimino was about himself in life, it's hard to separate his truth from lies in death.

Orson Welles

For all the ups and downs in his long life and career, Orson Welles was never bored or boring. In theater, radio, and film, he continually pushed boundaries as a writer, director, and actor. If his on-set behavior was sometimes difficult, he also impressed colleagues with a jovial demeanor. And however his films did at the box office, nobody could deny his talent.

But Welles had a curious insecurity as an actor and public figure: he thought his nose was too small. Author Joseph McBride, who wrote three books about Welles, told Laura Bannister that Welles was discontented with his face overall. "[H]e said he had the face of 'a rather depraved baby,'" McBride recalled. Not that Welles completely hated the way he looked, or his nose in particular. He just didn't think it was a good fit for his profession. "For all normal purposes, my nose is pleasant," he declared. "For dramatic purposes, I detest it."

To get around that, Welles regularly wore prosthetic noses on stage and in film. He had a collection of them, and he got double duty out of them by incorporating them into his magic tricks done for houseguests. According to filmmaker and critic David Cairns on his blog Shadowplay,He even named the noses, though not for the characters they went with. And Welles made no secret about it either. In television appearances, he volunteered to the audience that he looked so different because, unlike in movies, he didn't have a large fake nose on.

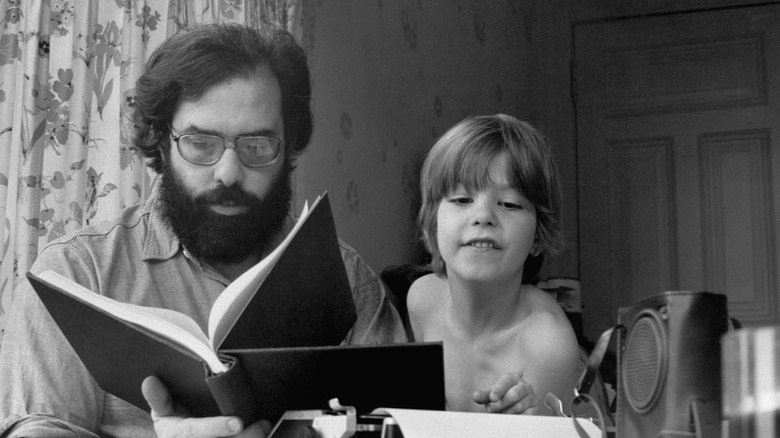

Francis Ford Coppola

For those who haven't had overwhelming success, it can seem strange that anyone should resent it. Yet Francis Ford Coppola has long been ambivalent about his position as a towering presence in Hollywood. "I had an impressive career as a younger person," he told Time in 2007, "but it was like an older director's. ... The younger director never had his moment." Films like "The Godfather" put Coppola at the top of the cinematic food chain, at least until the failure of "One from the Heart" left him digging his way out of debt for over a decade. Between those two pressure points, he was often constrained from taking the risks a young, experimental director might.

But "you can't be an artist and be safe," Coppola told The New York Times. After stepping back from professional filmmaking in the 1990s, Coppola did a series of self-financed independent films before going big on 2024's experimental epic "Megalopolis," defying naysayers in the press and the studio system. Even after an unsuccessful first run in theaters, Coppola's doubled down on his desire to experiment, taking "Megalopolis" on tour and vowing to re-cut it to "make it more weird" (via Word of Reel).

But even when in the midst of his Hollywood career, Coppola showed a maverick spirit in other ways. Many successful directors would have nannies or household staff to look after their kids while they went off on location to shoot a movie. Coppola pulled his children out of school to come with him on any trip longer than 10 days and raised them on the sets of his movies.

Tim Burton

Directors who make odd movies, and their families, sometimes resent the assumption that they must be weird in private. Stanley Kubrick's widow was very upset at the perception of her husband as a weird recluse. And Tim Burton has personally pushed back on claims that he's an oddball. Across many years' worth of interviews, he's insisted that he isn't strange.

"I never felt strange and, until this day, I don't feel strange," Burton told The Times in 2004. "I always felt like I was a normal person. ... Why I was categorized as strange, I have no idea. But from the beginning, I was." Ten years later, he was saying the same thing to The Times again, though he did volunteer monster movies as one reason people might find him weird. But his larger point — the arbitrary, unfair nature of categorization — remained the same.

And a true point it is. Still, even Burton's family has conceded that he's a little offbeat. While appearing on "The Graham Norton Show" (via YouTube), Burton's then-partner Helena Bonham Carter described their family Christmas as a traditional one ... except for one detail. The tree, which Burton maintained decorating control of, was loaded up with ornaments of zombies and dead babies. But at least he had arranged them in such a way that they weren't noticeable until you got up close.