'70s Musicians We Completely Forgot About

Among the things people get wrong about the 1970s is that it wasn't just all about disco. In fact, the 1970s just might be the most creatively explosive decade in music history. Several different genres emerged, were invented, or reached their artistic or popularity peaks in the decade, like singer-songwriter folk-rock, reggae, arena rock, soft rock, and, yes, disco. All those innovators generating exciting new forms of music made superstars out of a great many of them, despite the very messed-up 1970s music industry. While they may have recorded before the '70s and even into the following decades, they'll likely forever be publicly associated with that 10-year period; the human and creative equivalents of bell bottoms, tricked-out vans, and bicentennial fever.

So whatever became of those distinctively 1970s superstars? A lot of them couldn't keep up the fame when the tone of the culture changed, others faded out of the music scene by choice, and a few were cursed by fate and circumstance. Here then are some musicians who were on top of the world in the 1970s that we all seemed to forget in the years since.

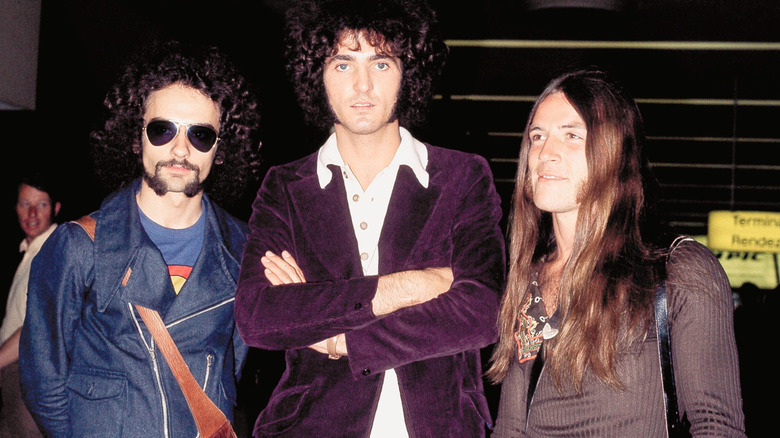

Grand Funk Railroad

One of the first hard rock bands to find mainstream success, Grand Funk Railroad (later known by just Grand Funk) churned out 10 albums between 1969 and 1974, and they all went gold or platinum. That was virtually unheard of for rock bands at the time, and the loud, relentlessly touring power trio also sold out Shea Stadium in New York in only three days, a feat only previously accomplished by the Beatles and over the span of weeks. The band's hard-charging boogie rock did well on the radio, too, as "We're an American Band" went to No. 1, as did its cover of the old pop chestnut "The Loco-Motion."

With its creativity and public interest slipping by 1976, Grand Funk Railroad stuck it out to work with Frank Zappa on one more studio album, before frontman Mark Farner tried to go solo, and the remaining musicians soldiered on as a new band called Flint. An early '80s two-album comeback attempt flopped.

The Raspberries

With its crunching guitars, hooks, and lush harmonies, the Raspberries was a significant proponent of an early 1970s pop-rock fad called power pop. Edgy but catchy songs like "Overnight Sensation (Hit Record)," "Let's Pretend," and "I Wanna Be With You" earned a lot of radio airplay, but its biggest hit, "Go All the Way," did better than all the rest. The No. 5 smash was rediscovered by Hollywood in the 21st century, and it's shown up on numerous nostalgic and '70s-set movie soundtracks.

The Raspberries' peak was brief. Most of its hits arrived in 1972, half the band left in frustration in 1973, and after officially splitting in 1975, frontman and main songwriter Eric Carmen embarked on a solo career, embracing a soft rock sound very different from the Raspberries. His most notable songs include the ballads "All By Myself" and "Make Me Lose Control." Carmen passed in 2024, and sadly was yet another '70s star who died without anyone noticing.

Seals and Crofts

Seals and Crofts were among the most commercially successful of the many gentle, sensitive, and warbling duos who took '60s-influenced folk-pop to the masses in the 1970s. Previously members of the Champs, one-hit wonders who deserved more than their 15 minutes of fame for their instrumental hit "Tequila," Jim Seals and Dash Crofts filled their recordings with acoustic guitars, woodwinds, and harmonizing, which were foundational for soft rock and adult contemporary radio. Between 1972 and 1978, Seals and Crofts scaled the pop and adult contemporary charts more than a dozen times with the likes of "Summer Breeze," "Diamond Girl," "We May Never Pass This Way (Again)," "Get Closer," and "You're the Love."

When the '70s ended, so did the partnership between Seals and Crofts. With their contract with Warner Bros. fulfilled and recognizing that their sound was on the way out, Seals moved his family to Costa Rica, and Crofts took his to Australia. They'd very occasionally reunite for concerts until Seals had a stroke in 2017, dying five years later.

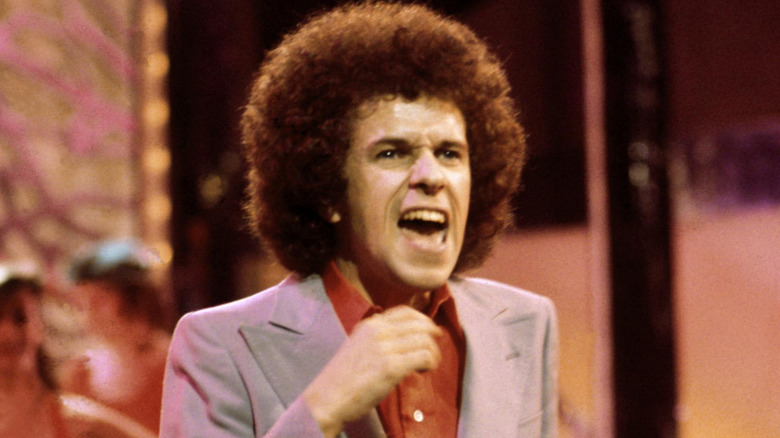

Leo Sayer

Something of an unlikely star, Leo Sayer presented many different sides of his creative self throughout the 1970s, yet never really sounding like anyone but Leo Sayer. Plucked from a failed duo called Patches, Sayer broke out after Roger Daltrey of the Who recorded some of his compositions, and then his 1973 single "The Show Must Go On" — a mix of banjo and theatricality sung in an anxious rasp — hit No. 2 in the U.K. Sayer then dropped that sound — and his stage look of a classical clown or mime — in favor of blues-rock and contemporary dress. "Long Call Glasses" marked Sayer's first American hit, setting the stage for the upper-register-employing soft disco track "You Make Me Feel Like Dancing" and the equally high-tuned ballad "When I Need You," both of which topped the charts in 1976 and 1977, respectively.

After another slow song, "More Than I Can Say" peaked at No. 2 in the U.S., Sayer never had another major hit in the U.S. again, but he continued to be a mild presence in the U.K. for a few more years before taking a long break from recording.

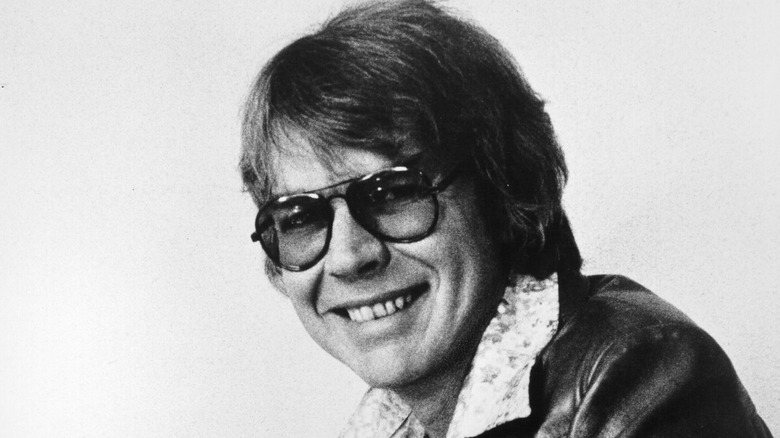

America

America was formed in the early 1970s; its three core members were U.S.-born former high school students living in the U.K., because their U.S. Air Force officer parents were stationed there. In 1972, the group benefited from the acoustic-guitar-wielding singer-songwriter craze and took its Neil Young-esque "A Horse with No Name" to No. 1 in the United States. On the strength of that song and similarly inward-looking hit folk ballads like "Ventura Highway" and "I Need You," America won the Grammy Award for Best New Artist. The band followed it up with the "Holiday" and "Hearts" albums in rapid succession, which spawned more soft rock standards in "Sister Golden Hair," "Tin Man," and "Lonely People."

Original member Dan Peek left America in 1977, and the band tanked for a while, only to stage a big comeback in 1982 and 1983 with "You Can Do Magic" and "The Border." The band would never reach its former level of popularity again, though America kept touring and quietly releasing albums into the 2010s.

Bread

One of the softest of all the soft rock acts of the early 1970s, Bread cooed quiet, understated songs of love and devotion that set the mood for romance and chill-out sessions. Co-fronted by James Griffin and David Gates, the acoustic guitar-driven band released a string of top-10 hits, starting with the No. 1 "Make It With You," followed by "It Don't Matter to Me," "If," "Baby I'm-A Want You," and "Everything I Own."

The band split up in 1973, with its initial period as a major act lasting only about three years. Bread had been founded on an equal songwriting partnership between Griffin and Gates, but when the latter's compositions became the ones that got the most attention and were picked as singles, Griffin objected. A reunion in 1976 would generate the hit song "Lost Without Your Love," but Griffin would depart again. Gates carried on as Bread with a new lineup, but Griffin sued to stop it, and they both pursued moderately successful solo careers instead.

Three Dog Night

One of the most important rock bands of the 1970s, Three Dog Night was a unique experiment. A hybrid between a vocal group and a rock act, three singers took turns on frontman duties to perform songs sourced from outside the band, all written by up-and-coming songwriters and obscure performers. And it all worked out: From 1969 to 1974, Three Dog Night sold more records and had more top-10 hits than any other rock band. Among the No. 1 hits, which helped to frame several movie scenes set in the early 1970s and still get classic rock radio airplay today, are Randy Newman's "Mama Told Me (Not to Come)," Hoyt Axton's "Joy to the World," and "Black and White."

After two backing musicians left in 1974, singer Danny Hutton departed a year later, and Three Dog Night didn't record anything until the flop 1983 New Wave release "It's a Jungle." Hutton eventually returned, Chuck Negron left, and Cory Wells remained as Three Dog Night toured the nostalgia circuit in the 1990s and beyond.

Anne Murray

In the 1970s, the lines separating soft rock and country blurred, thanks to line-toeing superstars such as John Denver and Anne Murray. While all the hip, young people were listening to hard rock, disco, punk, and New Wave, older North Americans preferred the sweet, calming, and docile sounds of Murray, a superstar in her native Canada who broke into the U.S. market in 1970 with the top-10 hit "Snowbird." As the decade wore on, Murray was more likely to strike it big on the country and adult contemporary chart than the all-genre Billboard Hot 100, but the frequent talk show and variety show performer was absolutely undeniable with her takes on modern standards like "Danny's Song," "What About Me," "Daydream Believer," and "You Won't See Me." In 1978, she even had a No. 1 pop hit with "You Needed Me."

As pop and adult contemporary radio changed in the 1980s, Murray's sound became dated, so she veered into country balladry full-time. By the time the '90s arrived, the movement to embrace old-school country music sounds came around, rendering her passé in that genre, too.

Melanie

The anti-war, pro-peace, and decidedly hippie countercultural movement of the 1960s didn't die when the calendar turned over to 1970. The vibes and aesthetics of the Baby Boomer youth carried on and evolved in the early 1970s, helped along by singer-songwriter Melanie. She performed on the first night of the Woodstock Festival in August 1969, and spectators lit candles as Melanie played during a rainstorm. That inspired Melanie's first hit, 1970's "Lay Down (Candles in the Rain)," which helped spread the legend and lore of Woodstock. She continued to score hits throughout the rest of the decade, including her take on the Rolling Stones' "Ruby Tuesday," the anti-music industry lament "What Have They Done to My Song Ma," and "Brand New Key." The latter went to No. 1 in 1971, despite radio stations across the U.S. banning it for its supposedly suggestive sexual metaphors.

Melanie became a part-time recording artist in the 1970s in order to raise a family, but resurfaced in 1989 with an Emmy Award-winning theme song to the TV drama "Beauty and the Beast," in 2007 with an acclaimed performance at the Meltdown Festival, and in 2012 with the autobiographical stage musical "Melanie and the Record Man." She died in 2024.

Andy Gibb

Among the many artists for whom the Bee Gees wrote music was Andy Gibb, the younger brother of members Robin, Barry, and Maurice Gibb. Only a baby when the Bee Gees formed in the late '50s, Andy Gibb got a major boost from his siblings when he was ready to launch his career in 1977. The pop rock act had reinvented itself as a disco act, and right around the time that it released the disco-classic packed "Saturday Night Fever" soundtrack, Gibb took every single he recorded in the 1970s to the Top 10, with his first three topping the pop chart: "I Just Want to Be Your Everything," "(Love is) Thicker Than Water," and "Shadow Dancing." Not only did Gibb sound like a Bee Gee, but he had the youth and good looks that were also quite favorable to '70s audiences, and he became one of the most adored teen idols of all time.

Gibb continued to notch hits into the early 1980s, but as disco grew unfavorable, he segued into acting and hosting. He was terminated from "Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat" and TV's "Solid Gold" because his drug addiction made him so unreliable. After a tabloid-friendly relationship with '80s star Victoria Principal of "Dallas," in 1988 Gibb died at age 30 from a viral inflammation of the heart, which had been weakened by years of drug abuse.

The Bay City Rollers

For a little while in the mid-1970s, it really looked like the Bay City Rollers could be the next Beatles, as its champions suggested, and if the behavior of its scores of primarily teenage and female fans was a proper gauge. Formed in Scotland — a point reiterated by the band's stage attire of tartan patterns — and named after a member threw a dart at a U.S. map that landed on Bay City, Michigan, the glam rock-inspired but bubblegum-marketed Bay City Rollers produced some of the most prominent teen idols of the decade. It placed 10 singles in the Top 10 in the U.K., a mix of energetic, danceable covers like the Four Seasons' "Bye Bye Baby" and Dusty Springfield's "I Only Want to Be with You," as well as rollicking originals such as "Shang-A-Lang" and "Money Honey." Rollermania briefly crossed the ocean into the U.S., too, with the stomping and chanting "Saturday Night" hitting No. 1 in 1976.

As is often the case with teen idol-type acts, the Bay City Rollers burned brightly but briefly, with fans moving on to the next sensation by 1978, by which point long-time members Alan Longmuir, Leslie McKeown, Ian Mitchell, and Eric Faulkner had all exited.

Badfinger

After moderate success in England and its native Wales as the Iveys in the 1960s, the band was discovered by associates of the Beatles and signed to that group's Apple Records. After a name change to the edgier Badfinger and the Beatles demo "Bad Finger Boogie," the group's "Come and Get It," recorded for the Ringo Starr movie "The Magic Christian," went top 10 in the U.S. and U.K. in 1970. Classified as a pop-rock and power pop band, Badfinger was quite the versatile hit machine, churning out the dreamy "Day After Day," as well as the crunchy, perpetual soundtrack favorites "No Matter What" and "Baby Blue."

The latter would mark the original iteration of Badfinger's final chart success. Sketchy business and record deals, including a manager absconding with most of the band's earnings, exacerbated the mental health issues of Pete Ham, who died by suicide in 1975. An early '80s comeback was short-lived due to lack of interest, followed by the tragic death by suicide of Tom Evans in 1983.

The Sylvers

Family bands were big in the 1970s, and while the Jacksons and the Osmonds are the most remembered acts, the Sylvers put up a big string of chart hits, rolling with the changing sounds of the '70s as it blended R&B, funk, and disco. Billed as the Memphis soul response to the poppier Jackson 5, nine singing Sylver siblings participated in the family business, which made it to the top 20 of the R&B chart in 1972 with "Fool's Paradise," the first of eight songs to reach that list. The Sylvers crossed over to the pop world, too, as "Hot Line" hit No. 5 in 1976 after "Boogie Fever" went all the way to No. 1.

The Sylvers had a couple more minor R&B successes in the mid-1980s, by which point the novelty of a large family act had worn off. After poor sales of a 1984 album and the death of non-member Christopher Sylver in 1985, the group broke up.

C.W. McCall

C.W. McCall is one of the most prolific country music hitmakers of all time who also happens to not be a real person. He was the persona of Bozell and Jacobs advertising executive Bill Fries, who created and played the truck-driving balladeer persona in commercials for Iowa's Mertz Baking Company.

Used in those bread ads was Fries' song, "Old Home Filler-Up An' Keep on-a-Truckin' Cafe," which sold 30,000 copies in the Midwest when released on Fries' private label, before MGM Records signed Fries as C.W. McCall and turned it into a Top 20 national country hit. More truck driver songs headed to the higher rungs of the country charts, and then in 1975, C.W. McCall scored a No. 1 pop and country hit with "Convoy." Capitalizing on the fad of CB radios — which had made their way from truck drivers' cabs into regular folks' cars as a way to relay info about speed traps and cheap gas — it was a story song about a heroic band of truckers. In 1978, the song was adapted into a movie of the same name.

Fries' alter ego had a handful of minor country hits afterward, and he went back to his career in advertising. Fries' co-writer, Chip Davis, went on to form the electronic/New Age act Mannheim Steamroller, which has sold more than 41 million albums, most of them Christmas releases.