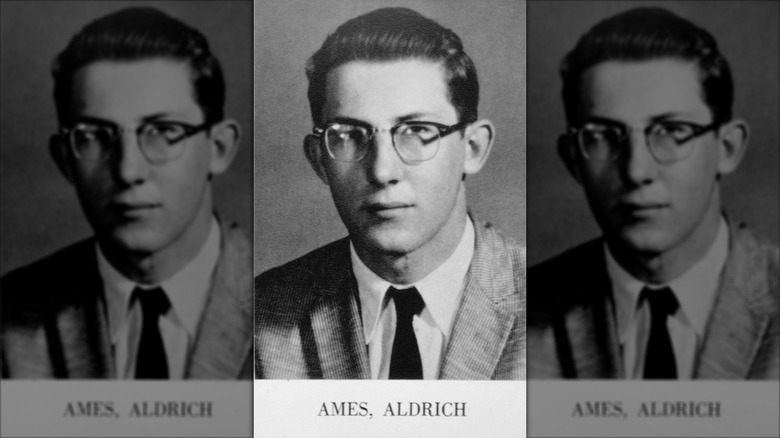

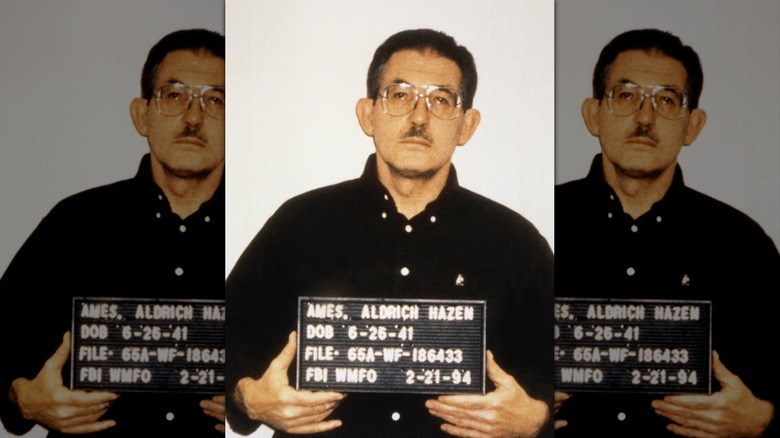

The Most Dangerous Double Agent In CIA History

The world of Cold War espionage brings to mind images of secret conversations, shadowy document hand-offs, and late 20th-century technology, along with perhaps a certain besuited agent suavely asking for a martini at a bar somewhere. But the reality of being a Cold War spy isn't quite like that. Moreover, the most dangerous double agent in CIA history, the one who may well have caused the most deaths and wreaked the greatest havoc, was no James Bond. Instead, he was a man named Aldrich Ames.

Far from dazzling the agency, Ames took a muddled course through the CIA beginning in the 1960s, with occasional glowing evaluations marred by problems with alcohol abuse, financial worries, personal upsets, and lackluster performance. Though Ames did rise through the ranks and began to work with Soviet contacts in an official capacity, he felt unsatisfied. So, in the mid-1980s, he approached the Soviets and began handing off classified information. The result: Multiple deaths, a near-complete cessation of CIA operations in the USSR, and some hefty payments deposited into the Ames bank account. Though Ames kept it up for years, he was eventually arrested and is now serving out a life sentence in federal prison, capping a winding story of deceit and international espionage.

He was a college dropout

Aldrich Ames hadn't originally planned to get involved in espionage at all. Sure, his father worked for the CIA, and he landed a temporary clerical job at the agency starting in 1957, while he was still in high school. But he went on to attend the University of Chicago in 1959, with the intent to major in some sort of history or cultural field. However, he was also passionate about theater, to the point where his grades began to suffer and he ultimately dropped out.

After some time working as an assistant technical director in a Chicago theater, he returned to the CIA and took on a full-time job doing clerical-level work for the agency. While holding this job, he finished a history degree from George Washington University in 1967. During this period, despite occasional brushes with the law related to reckless driving, speeding, and alcohol use, he received decent enough evaluations and consistent promotions. By the late 1960s, Ames — who once thought his time at the CIA was only going to last him through that college degree — was embarking on a path as a career operations agent. By the end of the decade, Ames and his first wife, Nancy Segebarth (another CIA trainee who was pushed to resign after their marriage), were assigned to a post in Ankara, Turkey.

His track record at the CIA wasn't exactly illustrious

Aldrich Ames showed some promise and was assigned to an operations post in Ankara, where he initially received commendable evaluations and another promotion. But then, his performance dipped. Three years into his assignment, higher-ups were beginning to think that Ames wasn't suited to the field at all and should go back to a desk job at headquarters. Ames himself later said he considered resigning around this time.

Returning to the CIA's base of operations in Langley, Virginia, and its Soviet-East European Division didn't necessarily spell a return to form for Ames. Coworkers and supervisors at the CIA noticed his problems with alcohol and his persistent procrastination. Yet, when he was assigned to an office in New York City in the late 1970s, he first earned glowing reviews, with some noting his particular skill with languages and well-written reports. Even so, there were rumblings of trouble. In 1976, while on his way to meet with a Soviet contact, Ames carelessly left a briefcase of classified documents on the NYC subway. In 1980, he left top secret communications gear out in his office. Still, neither incident garnered an official reprimand.

He had access to high-level classified information

Despite the initial sense that he would be best suited to professional life as a desk jockey, Aldrich Ames began working directly with Soviet contacts, first on American soil and then overseas. Again, he received middling reviews. As noted earlier in his career, he didn't quite have the charisma necessary for a field agent and continued procrastinating. Perhaps most alarming was his increasing pattern of alcohol abuse, leading to an incident in which he colorfully argued with a Cuban representative at an embassy reception in Mexico City. This led to official recommendations that he seek counseling, but this petered out after a single session.

Despite all of these issues, by September 1983, Ames was promoted to counterintelligence branch chief for Soviet operations. At this time, even before he truly turned traitor, he had misgivings about the CIA's work. Per the National Security Archive, he later said the CIA's "Soviet espionage efforts had virtually never, or had very seldom, produced any worthwhile political or economic intelligence on the Soviet Union." That point is perhaps up for debate, but it partially reveals how Ames was able to justify his turn to the KGB.

Ames believed he had serious money trouble

While some spies and double agents may be able to justify their turns for political, moral, or personal reasons, Aldrich Ames has admitted to another key motivation. In a post-arrest interview, he divulged that "it was a matter of pursuing an intensely personal agenda, of trying to make some money that I felt I needed very badly, and in a sense that I felt at the time, one of terrible desperation." Despite the series of promotions and occasional bonuses that accompanied Ames through his career, he felt that money was tight after the breakdown of his first marriage. That was hurried along by his overseas assignments and a developing relationship with Maria del Rosario Casas Dupuy, a staff member of the Colombian diplomatic team whom he'd met in Mexico City.

By 1983, Rosario had moved to the U.S. and began living with Ames. At this point, Ames had separated from his first wife, kicking off an expensive divorce process in which he agreed to pay off their accumulated debt. Faced with tens of thousands in dues, as well as the pressure to establish a household with Rosario (and her expensive tastes), Ames began to worry. As reported by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, he later reflected: "I felt a great deal of financial pressure, which, in retrospect, I was clearly overreacting to."

He initially meant it as a one-off betrayal

By the spring of 1985, Aldrich Ames had decided to contact the Soviets, hand over key information, and get a payout. Some accounts say he first approached a Soviet official at a Washington, D.C. party but didn't get far. Later, a determined Ames walked directly into the city's Soviet embassy and handed the receptionist an envelope. Inside was confirmation of his CIA affiliation, the identity of some double agents, and a request for $50,000. The KGB was certainly interested and took Ames on as a double agent.

Ames apparently meant this to be a one-time affair. "I saw it as perhaps [...] a very clever plan to [do] one thing," he explained in his Senate testimony. It was only later that he realized there was no turning back, saying, "[I]t came home to me, after the middle of May, the enormity of what I had done. The fear that I had crossed a line, which I had not clearly considered before." In another interview, he reiterated his sense that he'd somehow gone off the rails and was sleepwalking through the next steps of his relationship with the KGB. [W]hen I got the money, the burden in a sense of it descended on me [...] And it led me then to make the further step, which in a sense was to cast myself into it," he said.

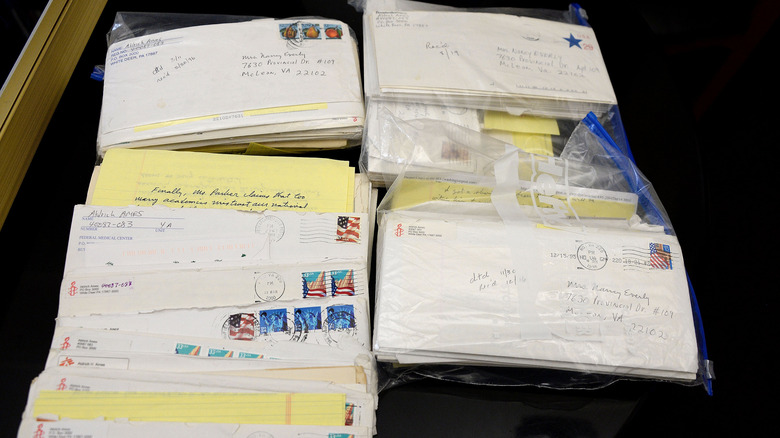

He relayed information via meetings and dead drops

When it came time to pass information along to his Soviet handlers, Aldrich Ames took a direct approach, often simply grabbing classified documents from his workplace, wrapping them up in plastic, and handing them over in person. Because he was supposed to meet with Soviet diplomats in the course of his legitimate work, it hardly raised suspicion when he was meeting with a Russian for lunch. Few knew that those meetings also included passing along information compromising double agents, informants, and technological advances that the U.S. had wanted to keep secret.

Sometimes, Ames did engage in a bit of slightly more daring espionage via dead drops (though not one of the more devious spycraft deceptions out there). An agent using a dead drop leaves documents or other information in a predetermined site, and someone else comes along later and picks up the intel. For Ames, this trade took the form of an unassuming USPS mailbox on which he left a swipe of chalk. If it was successfully retrieved, a KGB contact would erase the chalk to let Ames know the deed had been done.

The CIA realized something was wrong when people began disappearing

With Aldrich Ames' information in hand, the KGB began to act quickly. Beginning in the fall of 1985 and into 1986, about 20 CIA agents in the Soviet Union abruptly disappeared. An operational flub might mean one or two agents could be arrested, but 20? Little else but a double agent could explain the sudden upset of the conventional rules of spycraft. And it wasn't hush-hush, either — by 1986, even The Washington Post was reporting that, after all the arrests, the KGB might run out of spies to apprehend.

Yet, the CIA moved slowly despite the shocking development. Besides slow-moving bureaucracy and a necessarily methodical investigation, part of the blame goes to the culture of paranoia and disillusion that had taken root in the agency. Anyone could be a spy, and so the communication and collaboration needed to catch a mole like Ames was hampered by this anxiety. For a time, other explanations also seemed possible, from an exploited computer vulnerability to even the work of a really, really good (or just lucky) KGB agent. Moreover, the CIA might have been embarrassed, as admitting there was a mole and collaborating with the FBI for a domestic investigation meant owning up to a serious failure.

At least 10 contacts died as a result of the espionage

It's hard to overstate the devastating effect of Aldrich Ames' betrayal. The KGB response effectively ended all CIA work in the Soviet Union and led to the executions of major assets like General Dmitri Polyakov (above). Some, like KGB official and double agent Oleg Gordievsky, barely escaped (though it may not have been among the most unbelievable Cold War escapes, Gordievsky did have to hide in a car trunk for part of his journey).

Later, Ames admitted that he did a fair amount of mental work to wave away the potentially deadly consequences of his betrayal. In one interview, he explained how he had initially shrugged off the usefulness of espionage in general. "[I] had come to the conclusion that the loss of these sources to the United States Government, or to the West as well, would not compromise significant national defense, political, diplomatic interests," he explained. Later in that same interview, he focused on his blind spot regarding the human cost, saying he simply didn't think it through. "I'm sure I must have thought in terms of 'These guys will actually be okay in certain ways, because of their need to protect me,'" he said, "but that was about as far as I went in terms of giving that consideration."

Women were key members of the team that took him down

If you think of an old-school CIA mole hunt team, chances are you just pictured a bunch of men. But, by the time the CIA had assembled that team in 1986 (codename Play Actor), that group included a number of highly skilled and very determined women. In fact, women have a long history as CIA agents, despite longstanding sexism.

This included Jeanne Vertefeuille, Fran Smith, and Sandra "Sandy" Grimes, who were assigned to the team partially because of the prevalent belief at the agency that "little gray-haired old ladies" were the only ones capable of combing through the files (never mind that the group also included women of different ages as well as men). They proved more than capable of going through mountains of data, teasing out a complicated web of relationships, movements, and finances. But pinning the espionage on a particular individual was supremely difficult, and the team was often left with few real leads ... even when the mole was sometimes right next door. In the 1970s, Grimes had worked in the Soviet division and was part of an office carpool, which sometimes meant catching a ride in Ames' old Volvo. Presumably he dipped out of the carpool once KGB money got him a succession of Jaguars. Later, a post-arrest Ames also admitted he had given Vertefeuille's name to the KGB to possibly frame her for his espionage.

Overspending was part of Ames' downfall

When Aldrich and Rosario Ames gained access to KGB money, they didn't exactly hole it away in a savings account. Indeed, they went a bit wild, spending their illicit funds on noticeable luxuries like multiple Jaguar cars and an Arlington, Virginia home worth $540,000 — a price they had paid in cash. Ames also paid for Rosario's education at Georgetown University, a prestigious and expensive private institution, and sent funds back to her family in Colombia. Ames occasionally attempted to cover the odd gap between his modest CIA salary and all that spending, once claiming they'd received an inheritance from Rosario's family. He told others that the house was purchased by an uncle who was unusually pleased about the birth of the Ames' son. He also attempted to move money amongst multiple accounts, using a touch of Swiss banking to keep things quiet.

Then Diana Worthen, a fellow CIA employee who had worked for Ames, became friends with Rosario. When the two discussed the Ames' new home in the late 1980s, Rosario mentioned the cash payment and spendy remodeling plans she had for the residence. Worthen, who knew how much Ames was making, grew suspicious and brought her concerns to the CIA mole hunt team. The CIA opened a financial inquiry into Ames, which revealed three alarmingly large deposits into his bank account through the 1980s.

The FBI began monitoring Ames in 1992

Digging into Aldrich Ames' financial records, investigator Sandy Grimes saw that whenever hehad a meeting with a Soviet official, there would be an oddly large deposit in his bank account soon after. At this point, the team included FBI agents who would be tasked with finding a traitor in U.S. territory.

Part of the investigation required sitting at a desk and poring over reams of documents, but once it turned towards Ames, more involved techniques were required. Agents covertly followed Ames, bugged his phone lines, and installed other listening devices in his workplace, home, and even car. The agency even used a small Cessna airplane dubbed the "Flying Screw" to surveil his movements (though neighbors complained about the low-flying plane over Arlington). This also meant that a team had to get into Ames' home — with keys, according to former FBI deputy director Bear Bryant, who spoke to NPR about the case — then break out the drills, bugging equipment, and drywall patches.

While the bugging provided key evidence, the real break came when agents went through the Ames family garbage in October 1993. They found a small Post-it note detailing a meeting with a KGB contact in Bogota, Colombia. The FBI tailed him to South America and recorded the meeting, though they didn't get clear evidence of an exchange.

He was finally arrested in 1994

Nearly a decade after his first act of espionage, Aldrich Ames was arrested in early 1994. Even when the CIA and FBI had good evidence that Ames was committing espionage, agents hoped to catch him in the act of passing something off or receiving a payment. That didn't pan out, however, and things grew worrisome. When Ames was arrested at his home in February, it was a mere day before he was set to fly to Moscow. Though it was an official CIA trip — Ames had by then been taken out of counterintelligence and transferred to a counternarcotics division — agents worried that he would flee the country.

As it was, Ames was arrested at his Arlington home that day. He was charged with conspiracy to commit espionage and tax evasion; Rosario faced the same charges after her own arrest. Both willingly gave over their assets to the U.S. and pleaded guilty. Rosario was given a 63-month sentence and has since been released, but her husband was sentenced to life and remains in prison. While others convicted of espionage have been released, Ames' supremely damaging work all but ensures that he will spend the remainder of his life in prison.

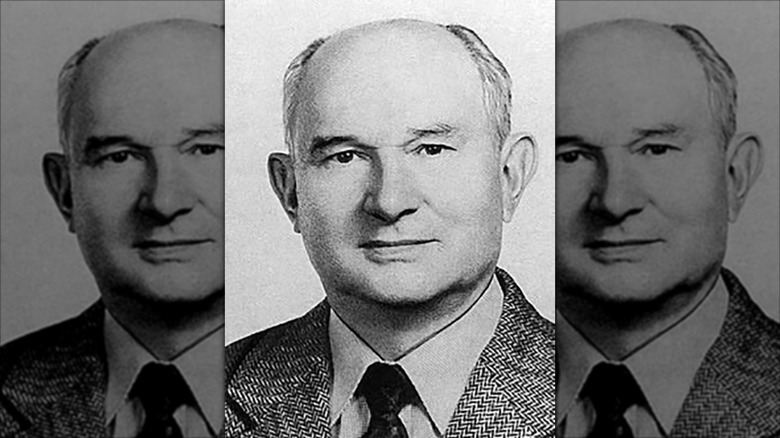

Ames wasn't the only mole in that era of the CIA

Though Aldrich Ames gained infamy for what's since been called the worst espionage case in U.S. history, he was hardly alone in his work. There was also Edward Lee Howard, a CIA officer who eventually defected to the Soviet Union (and died there, perhaps suspiciously, in 2002). Meanwhile, Robert Hanssen was an FBI agent who fed information to the Soviet Union and then Russia from 1979 until 2001, handing over so much classified info that the ill effects of his espionage rival that of Ames. Hanssen was apprehended, sentenced to 15 life terms, and remained in federal prison until his death in 2023. In fact, Ames' arrest led the FBI to realize that the agency had its own mole, leading to the investigation that caught Hanssen.

But some have argued that these three men did not have access to all the information that Russian agents received, meaning there very well could be a "fourth man" who has evaded capture to this day. Some suspects, including alarmingly high-up officials, were suggested but never definitively identified.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).