What Happened To The Confederacy's Leaders After The Civil War

Four years is a long time for a war to last, and a very short time for a country to exist. But 1861 and 1865 are the beginning and end dates for the Civil War, which pitted the extant U.S. government and its military against the Southern U.S., a collection of states that formally left the Union in order to form a new nation, the Confederate States of America. The reasons for war were complex, involving issues of economics, independence, democracy, and the tenuous relationship between sovereign states operating under a federal government. But really, the Civil War wasn't about states' rights — it was about slavery. The Union wanted to stop the expansion of slavery, and the Confederate states wanted to continue the practice unabated.

The Reconstruction Era was a truly messed-up and agonizing period of American history. In the decade or so after combat ended, the two sides continued to wage political, philosophical, and personal battles. The victorious United States government agonized over how to move on from the massively deadly war, and if and how to punish and reintegrate Confederate secessionists, sympathizers, and top government and military officials in the failed rogue government. Eventually, most major Confederate figures (who didn't die in the war) were accounted for, and had to answer for their actions before they were allowed to move on. Here's what happened to every important leader in the Confederacy in the years after the Civil War ended.

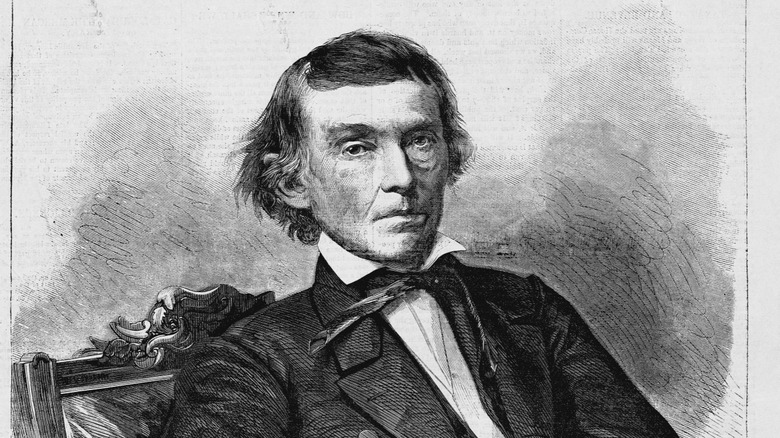

Jefferson Davis

Before the schism that led to the creation of the Confederate States of America and the Civil War, Jefferson Davis was firmly on the side of the United States. He fought in the Mexican-American War, and after a short term in the House of Representatives, President Franklin Pierce appointed him secretary of war in 1853. While acting as Mississippi's senator and with secession looming, Davis served on a committee seeking compromise instead of war, but when his home state left the Union, he abdicated his seat. At a meeting of the Confederate Congress, the politically experienced Davis was chosen by delegates in 1861 to be president of the Confederacy for six years. After the Civil War, one of the most devastating military defeats in modern history, the Confederate States of America became a country that didn't exist anymore, about four years into Davis' term.

At war's end, Davis made a hasty exit from the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, to avoid Union troops, who arrested him in Georgia five weeks later. Incarcerated for two years, Davis was released in 1867 after a contingent of Unionists paid his bond. After traveling through Canada, Cuba, and Europe, Davis stood trial for treason in late 1868. The court decided against punishing Davis, and he retired to an estate in Mississippi. He wrote his memoir and nearly took back his Senate seat, until it was decided his actions in the Civil War legally precluded that. Davis died in 1889.

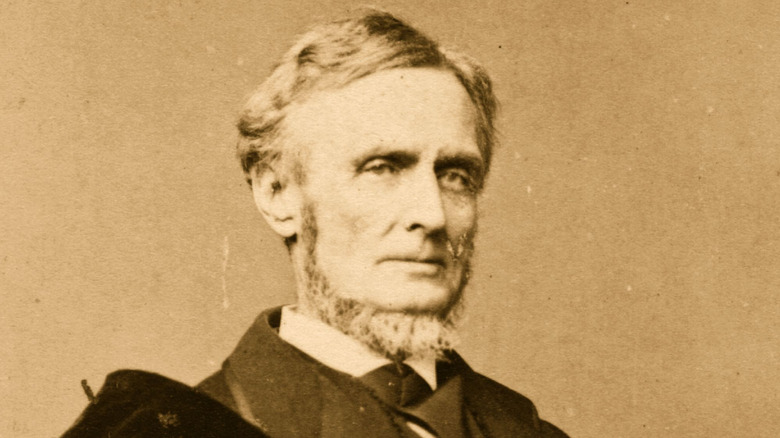

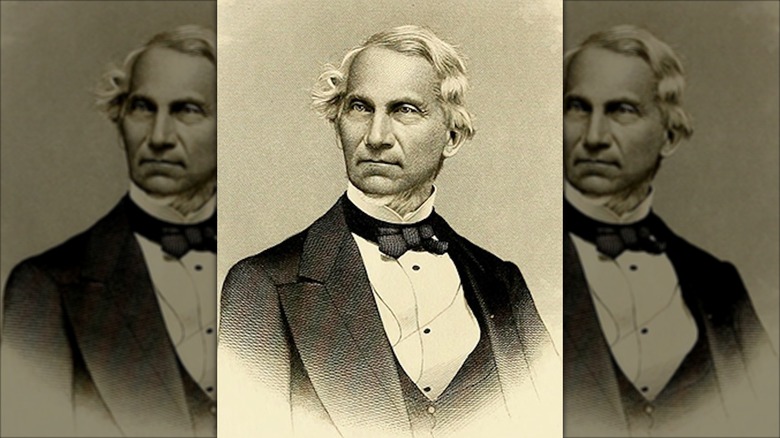

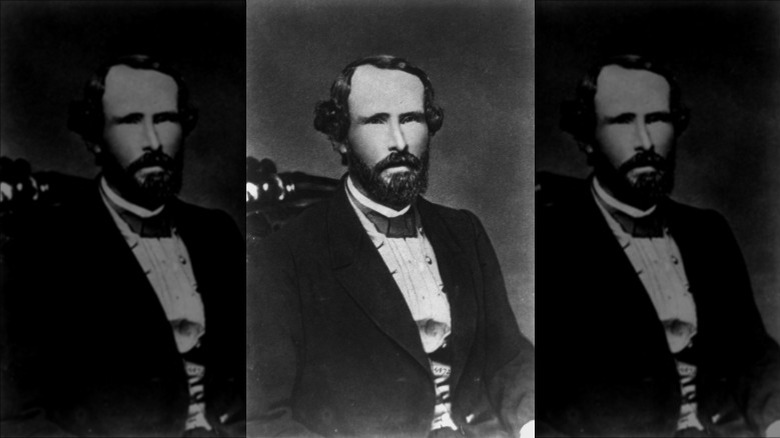

Alexander H. Stephens

While there have been a few powerful vice presidents in U.S. history, there's only one vice president in the history of the Confederate States of America. That would be Alexander H. Stephens. A Georgia state representative and senator promoted to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1843, Stephens held his seat until 1859, frequently supporting states' rights issues and compromise legislation that delayed but didn't stop the Civil War. The Confederate Congress picked Stephens to be vice president partly because of his history of moderation, a quality thought to be useful in getting border states to join the Confederacy.

Although Stephens tried to develop an armistice with the U.S. government in 1865, he was arrested and sent to the prison at Fort Warren in Boston. Five months later, he was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson. He immediately tried to get back into politics and, in 1866, secured a spot in the U.S. Senate, which refused to seat him. While he'd be admitted into the House of Representatives in 1873, Stephens spent the years in between writing books, including an account of his Civil War political machinations and a U.S. history book. In 1883, Stephens died at age 71, just months after being inaugurated as the governor of Georgia.

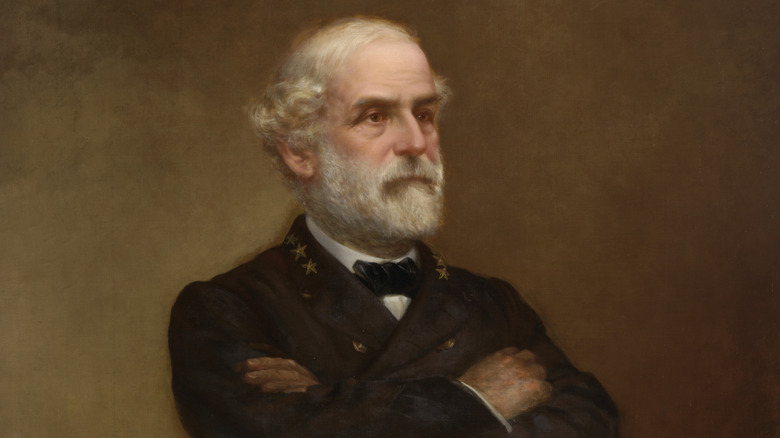

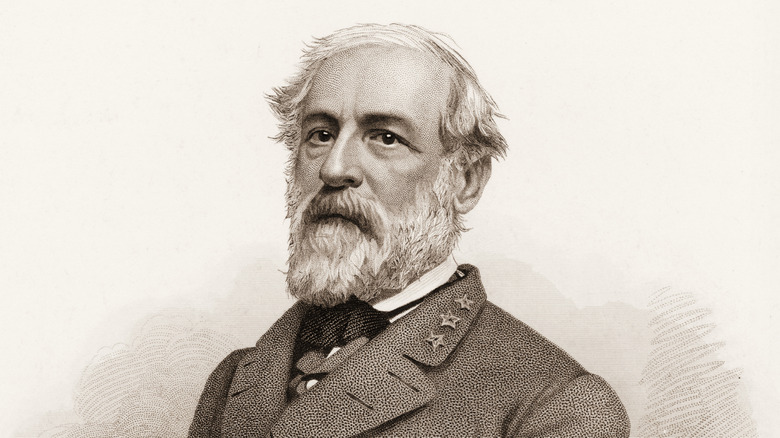

Robert E. Lee

When it appeared as if Southern states would secede, Robert E. Lee, a military star who acted as a captain during the Mexican-American War in the 1840s and quelled the ill-fated slave uprising at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, was offered the command of the Union forces. Instead, the Virginia-born Lee quit the U.S. Army in 1861 and was made the commander of Virginia's armed forces. Ultimately the leading military mind and general for the Confederacy throughout the Civil War, Lee was present at multiple significant battles and advised President Jefferson Davis.

In April 1865, on behalf of the Army of Northern Virginia and the entire Confederacy, General Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Lee's rank meant he was excluded from President Andrew Johnson's initial amnesty order in May 1865, but he signed an amnesty oath in October. He was never given a full pardon, and he only had his citizenship status returned posthumously, in 1975.

In the months after the war, Lee testified before Congress in part about race relations, where he attested that Black people should be allowed to attend school but not be given the right to vote. With his home and plantation in Virginia taken over by the U.S. government in the middle of the Civil War, Lee spent the rest of his life — he died in 1870 — working as the president of Virginia's Washington College

Judah P. Benjamin

Also known as the "Brains of the Confederacy," Louisiana senator Judah P. Benjamin quit in 1861 to defect to the just-formed Confederacy, where he was appointed attorney general. Also serving as secretary of war and secretary of state, unofficially Benjamin was President Jefferson Davis' top advisor. In that position, he took the blame for numerous Confederate blunders, such as when the Union captured Roanoke Island in South Carolina. He resigned one cabinet job and was appointed to another, kept in office despite a recall effort. Benjamin's high-level Confederacy activities came to an end after his 1864 speech to the rogue nation's senate, in which he suggested freeing enslaved people, giving them guns, and letting them fight on the front lines. The idea was soundly rejected.

In the last year of the war, and with the Confederacy consistently outmatched by the well-provisioned Union forces, Benjamin and other members of the Davis administration moved around the South as Northern troops advanced and captured territory. Just after the end of the war, and after President Abraham Lincoln was shot and killed, Secretary of State William Seward investigated Benjamin as a potential organizer of the assassination. There was ample evidence that Benjamin had orchestrated a Confederate spy network, which included gunman John Wilkes Booth. Nevertheless, Benjamin left the U.S. in favor of England, where he lived unbothered under the assumed name of Philippe Benjamin and worked as an attorney until his death in 1884.

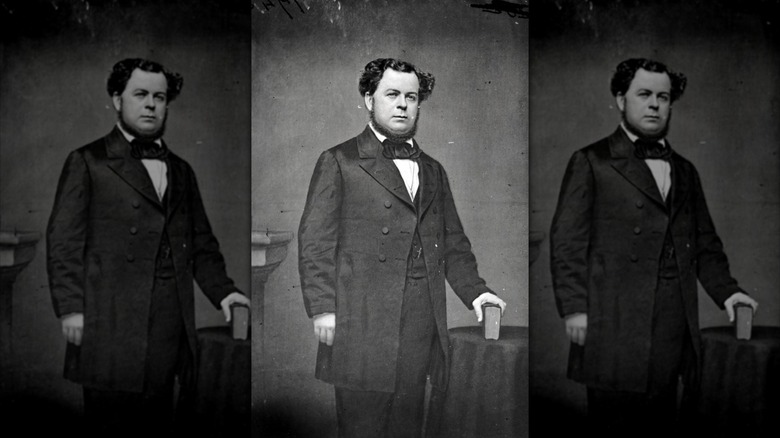

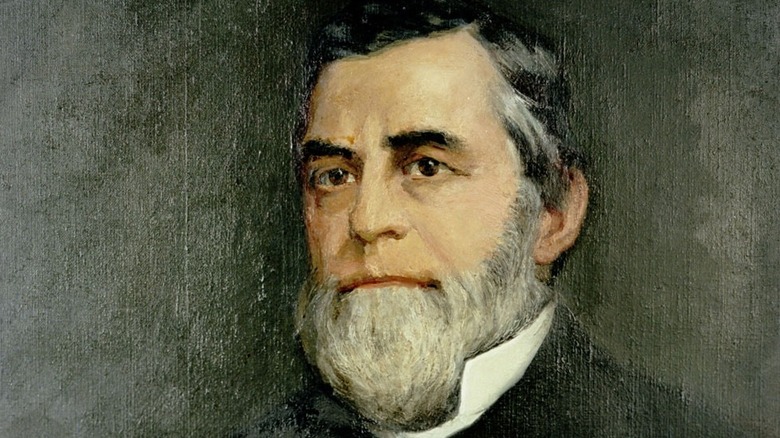

Christopher Memminger

The Confederate Constitution was different from the U.S. Constitution in that it explicitly outlined states' rights and championed slavery. The main author of the document that outlined the aims and beliefs of the Confederacy was Christopher Memminger, the lawyer selected to head up the Confederate States of America's Treasury Department. Memminger was also a member of the South Carolina state house and a political theorist who wrote "The Book of Nullification," an anti-federal government screed on the importance of states' rights. That led to a spot on the Secession Convention of South Carolina, where Memminger helped make his state the first to leave the U.S. and make the Civil War an inevitability. As treasurer, Memminger faced great difficulty running a country that at first had no currency and barely an economy on account of a successful U.S. blockade that prevented the export of valuable Confederate cotton.

Pardoned by President Andrew Johnson for his wartime activities in 1867, Memminger returned to South Carolina's state legislature, where he worked as the head of the Ways and Means Committee to help re-establish the state's war-ravaged credit. Memminger then served as Charleston's public schools commissioner, calling for compulsory education for children of all races. After calling for a railroad to unite the disparate regions of the state, Memminger took a position as the president of a railroad company. He died in 1888.

John H. Reagan

Texas' top figure in the government of the Confederacy was John H. Reagan, a lawyer, judge, lawmaker, and, as of 1857, member of Congress. He was in favor of keeping the country together until he became a secessionist after the raid on Harpers Ferry. Reagan represented Texas in the Confederate congress, but President Jefferson Davis plucked him for the cabinet-level position of postmaster general, an important position at the time because the job required maintaining the primary communication method during wartime.

Reagan was arrested by Union troops in Georgia in May 1865 alongside Davis and ex-Texas governor Francis Lubbock. Reagan then spent 22 weeks in solitary confinement at the prison in Fort Warren in Boston. While incarcerated, he wrote a widely published open letter to the people of Texas, beseeching them to reject the concepts of slavery and the Confederacy and respect the authority of the U.S. federal government, controlled by Abraham Lincoln's Republican Party. A political and social pariah upon his Texas homecoming in late 1865, he won back the support of a bitter electorate after he helped to expel Republican governor Edmund Davis in 1875. Reagan regained his old spot in the House of Representatives, was elected to a U.S. Senate seat, became the head of Texas' Railroad Commission, and helped write the state's revised constitution. The last surviving cabinet officer of the Confederacy, Reagan died of pneumonia in Palestine, Texas, in 1905.

Stephen Mallory

Both the political and practical head of the Confederate navy for the entirety of the Civil War, Stephen Mallory previously worked as a customs official in Florida, fought for the U.S. Army in the Second Seminole War in the 1830s, surveyed the Everglades, and landed in the U.S. Senate. Eleven years into his service, he resigned to join the Confederacy in 1861. His comfort with waterways and his military background made Mallory a logical choice for the position of secretary of the navy. He was charged with building, with extremely limited resources, the departmental framework of the Confederate navy as well as its fleet — one that would have to contend with the substantial, well-appointed U.S. Navy.

Mallory spent about a year in prison before he was paroled. Legally barred from seeking political office (until he was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson), Mallory opened a law practice in Florida and publicly expressed his opposition to giving Black Americans the right to vote. Mallory died in 1873.

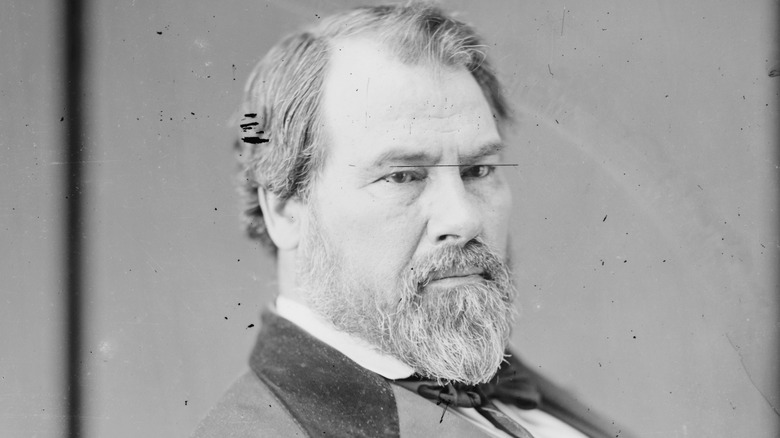

James Longstreet

One of the Confederacy's top military officers, General James Longstreet was outranked in the leading Army of Northern Virginia only by Robert E. Lee. Longstreet commanded soldiers in some of the most important battles of the Civil War, including the Battle of Manassas, the Seven Days Battles, and the pivotal and massively deadly Battle of Gettysburg. After an assault on Union Army troops failed to secure victory, Longstreet delivered the Confederacy a win at the Battle of Chickamauga, then was injured by friendly fire in Virginia. He made it back to the front lines just in time for Lee to surrender and end the Civil War.

After spending four years fighting the armies of President Lincoln, Longstreet changed his views. He joined the slain president's Republican Party as it instituted reforms and integration through legislation and acts of government throughout the South. Settling in New Orleans, Longstreet made a fortune in the insurance business and railroads. Disliked by the Southern Democratic political establishment for his increasingly liberal, pro-Northern views espoused in newspaper editorials, Longstreet moved to Gainesville, Georgia, in 1875, bought a farm and a hotel, held local political positions, and served as the U.S. ambassador to Turkey. After a brief period as a U.S. marshal in Atlanta was marred by charges of corruption, Longstreet was fired and retired to his farm until his death in 1904.

George Pickett

The Confederacy's tactics in the Civil War were primarily defensive, both ideologically and from a military stance. But its armies did mount a few attempts to invade the Union states, such as the last one: Pickett's Charge during the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Confederate soldiers stormed Cemetery Ridge but were met with substantial firepower as they moved across a wide-open area. It was all over in an hour, during which time 6,555 Southern troops died. One of the leaders of the three divisions that suffered such tremendous losses: General George Pickett.

Worried that he'd be tried for war crimes for his role in the execution of captured Union troops in 1864, Pickett departed the U.S. upon surrender. After receiving word that the government wouldn't pursue a trial, Pickett moved back to Virginia and found work as an insurer and farmer. After receiving a pardon from Congress in 1874, Pickett died a year later.

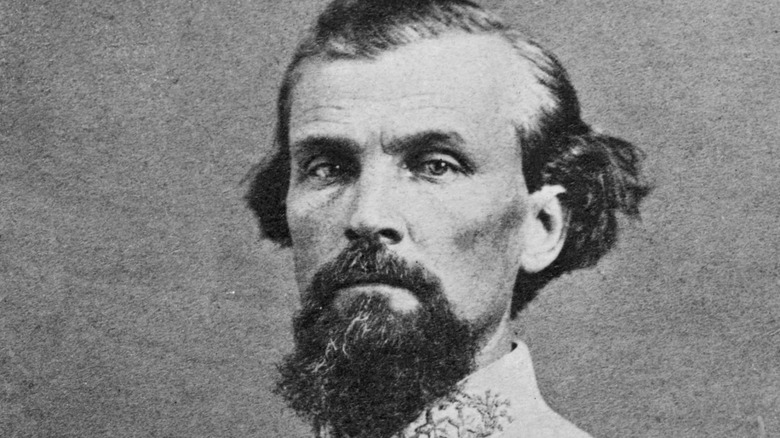

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Before the outset of the Civil War, Nathan Bedford Forrest was a millionaire, obtaining his wealth via the sale of cotton, land, and enslaved people. When war was declared, the prominent Southern citizen enlisted in the Confederate army as a private, then abandoned the post in order to form and fund his own military unit. Officially given the rank of lieutenant colonel, Forrest and his troops fought at Fort Donelson, escaping when facing surrender, and then at the Battle of Shiloh. He'd rise again, to the rank of brigadier general and then major general, and in 1864, Forrest's men laid waste to the Union stronghold of Fort Pillow, summarily executing many of the surviving Black troops.

After he offered his own surrender when the Confederacy gave up the war, Forrest continued to promote the racist ideology he had fought for, namely the subjugation of Black people. The Ku Klux Klan began as a Confederate veterans club, but it was reborn as a network of political organizations and hate groups in 1868 under the direction of Forrest, the revived KKK's first top official, or Grand Wizard. The KKK, with Forrest in charge, executed a campaign of intimidation, terror, and violence to stop formerly enslaved people from exercising their right to vote. Forrest's group of hooded Southern men were among many organizations that killed more than 3,000 people in the run-up to the 1868 elections. The KKK as Forrest knew it continued to exist well into the 20th century; Forrest died in 1877.

George W. Randolph

Born at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello estate, George Wythe Randolph was the grandson of the Founding Father, and he would eventually serve in the U.S. Navy and earn his law degree from the University of Virginia. After the slave rebellion of John Brown's raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859, Randolph, by then a Richmond City Council member, reacted by creating a volunteer rogue military regiment. He'd attain his officer commission in the Confederate army within the first few months of the Civil War, and by 1862, he was named the secretary of war under President Jefferson Davis, with whom he constantly clashed regarding military issues. He resigned after eight months on the job.

Due to a combination of political disagreements with Davis and declining health due to tuberculosis, Randolph left the Americas in November 1864 for Europe, sneaking out on a smuggling ship to avoid a U.S. blockade. He waited out the post-war heat and potential for arrest, only returning to the reconstituted U.S. in September 1866 after signing a loyalty oath. A month later, he lost his ability to speak, and six months after that, Randolph died of the effects of tuberculosis at his family's plantation in Virginia.

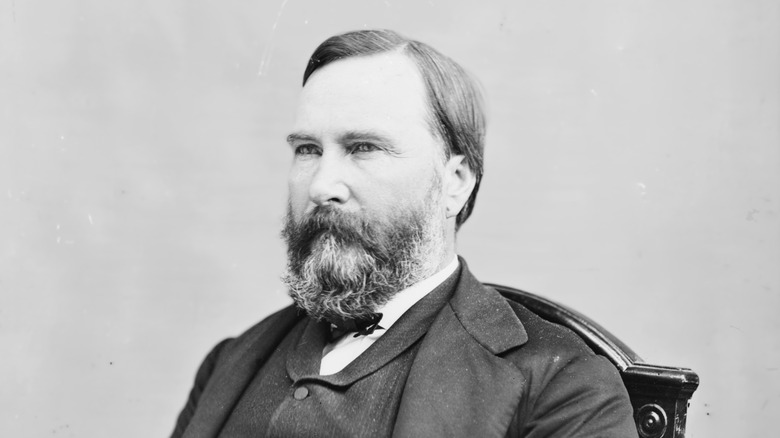

Thomas Bragg

It took decades for Thomas Bragg to rise through the North Carolina political system. A county solicitor and state representative, he was the governor from 1855 to 1859, with his main administrative achievements being the expansion of the state's banking system and revamped railroads. A staunch and vocal supporter of the Southern theory that states should be allowed to choose for themselves if they wanted slavery to be legal, Bragg was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1858. The Senate kicked him out in 1861 as a civil war over that exact subject approached. Almost immediately, Confederate president Jefferson Davis named Bragg to replace Judah Benjamin as his attorney general.

During Reconstruction, Bragg kept fighting the Civil War on the battlefield of ideas, publicly taking a stand against the progressive, post-slavery racial laws instituted and enforced around the South. As a member of the Conservative Party, he called out integration as the work of a radical government run amok. In 1871, he led a team of lawyers that impeached and convicted North Carolina governor William Woods Holden for supposedly capitulating to Washington, D.C., by trying to stop the Ku Klux Klan from operating. Within a year, Bragg died.