The Bizarre Truth Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde

First published in 1886, Robert Louis Stevenson's novella Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is one of a handful of literary works to transcend its era and pass into the lexicon of popular culture. Even those who've never read or seen a stage or film adaptation of Stevenson's book are familiar with its premise and title character(s). In the century since its publication, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has traversed the collective consciousness, evolving from popular novel to horror and science fiction trope to cultural shorthand for the duality of good versus evil. Like Dracula and Frankenstein's monster, Dr. Jekyll and his sinister alter ego are ever-evolving, and therefore constantly relevant, archetypes that form a psychological framework on which generation after generation has hung its collective fears.

Nevertheless, like Mary Shelley's monster and Bram Stoker's vampire, the pervasive popular conception of Stevenson's mad scientist as a trope and an archetype exists almost wholly outside of the text that spawned him. Although countless movies, comic books, cartoons, and parodies may have blunted Jekyll and Hyde's thematic edges to the point of cliché, Stevenson's novella retains its impact as the book that terrified and captivated audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. This is the bizarre truth of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

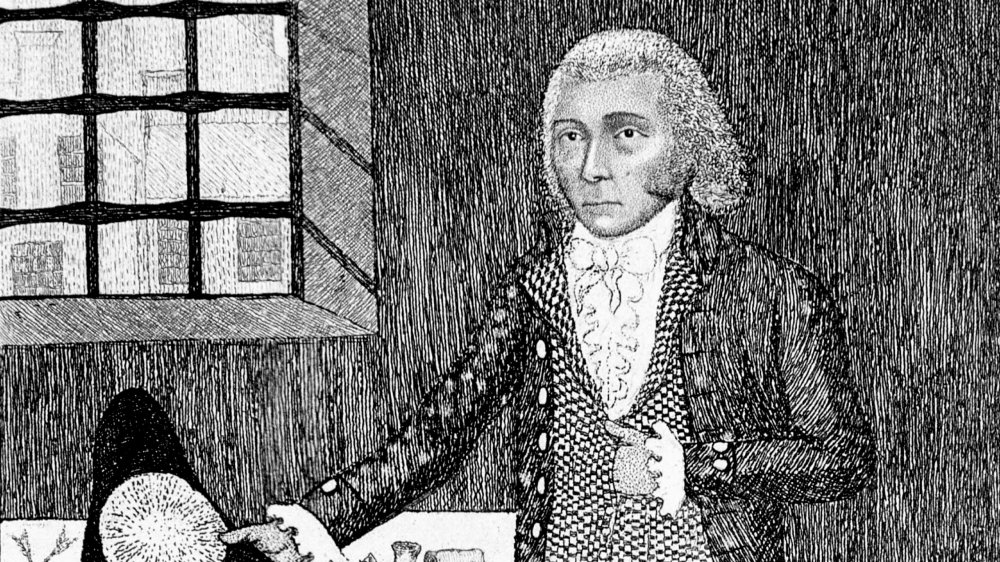

The novel was inspired by a real-life Jekyll and Hyde

For his model of sinister duality, Stevenson looked to the life of Deacon William Brodie. A respected city councilman and carpenter, Deacon Brodie walked the streets of Edinburgh a paragon of mid-18th century virtue. A skilled craftsman, he was the head of the trade guild The Incorporation of Wrights and Masons. Making his living as a cabinetmaker and locksmith, he was a well-trusted tradesman who crafted keys and repaired locks and doors for the city's wealthy and elite.

Yet, behind Brodie's facade of genteel respectability lurked a craven criminal. As recounted by the BBC, Brodie's secret penchant for late-night drinking, gambling, and cockfighting in an unsavory tavern in Edinburgh's Fleshmarket Close led to his secret life as the leader of a gang of burglars. Using duplicate keys and his skills as a locksmith, Brodie and company could enter any home or business unfettered, leaving behind no trace of entry. Deacon Brodie's luck ran out when he was implicated in an audacious attempted armed robbery of Edinburgh's Excise Office. Sentenced to death, Brodie's trial lasted a mere 21 hours. He was hanged in front of a crowd of 40,000 spectators, ironically, on a gibbet he had recently redesigned.

Stevenson, obsessed with the dichotomy inherent in human nature, found fertile dramatic ground in Brodie's sordid tale. With the help of his friend W.E. Henley, Stevenson wrote a play based on the diabolical deacon's life. Although that production ultimately failed, it sowed the seeds for Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Much of Jekyll and Hyde came to Stevenson in dreams

From childhood, Robert Louis Stevenson had vivid nightmares. An invalid from birth suffering from a malady termed "weak lungs," later likely misdiagnosed as tuberculosis, the author of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde spent much of his early years bedridden. With no physical outlet, the sickly Stevenson turned inward, developing a love of books and a rich imaginative life.

Writing of his childhood dreams in an 1888 essay, the author explains, "He was from a child an ardent and uncomfortable dreamer. When he had a touch of fever at night, and the room swelled and shrank, and his clothes, hanging on a nail, now loomed up instant to the bigness of a church, and now drew away into a horror of infinite distance and infinite littleness, the poor soul was very well aware of what must follow..." It would be this fusion of chronic illness and dreams that fueled the writing of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

In the autumn of 1885, a feverish and heavily medicated Stevenson, suffering from a lung hemorrhage, screamed out in his sleep. Distressed by her husband's cries, Stevenson's wife, Fanny, stirred the author from his fitful sleep. As detailed in Graham Balfour's biography, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, the indignant writer was not at all grateful for his wife's intervention. "Why did you wake me?" a furious Stevenson asked. "I was dreaming a fine bogey tale." Apparently, he had dreamed up until Jekyll's first transformation into Mr. Hyde.

Stevenson's wife saved Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Robert Louis Stevenson's wife, Fanny, was his most ardent supporter and, at times, his most brutal critic. Despite her husband's enthusiasm for his new novella, the first draft allegedly composed in the course of three days, Fanny felt the work, conceived as a "shilling shocker" (lurid, often violent novels popular among the lower classes during the Victorian era), beneath his talents. In a letter to Stevenson's friend and occasional literary partner W.E. Henley discovered in 2000 (via The Guardian), Fanny decries the first draft as "a quire full of utter nonsense" and threatens to burn it. Fanny, herself a skilled poet and writer of short stories, pulled no punches when it came to her husband's writing. She hated it. It was, in her words, "distasteful" and devoid of thematic weight.

Stevenson, who valued Fanny's judgment as an editor above all, knew she was right in her assessment of Jekyll and Hyde. The author had written the novella as a simple narrative. The first draft of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was missing the allegorical elements that elevated it from a mere horror story to one of the greatest novels of all time. According to one of the many legends surrounding the novel's composition, Stevenson, or perhaps Fanny, as the Henley letter seems to indicate, burned the original manuscript. With Fanny's notes and astute assessment of his work in mind, Stevenson went back to work, completing a second draft of the 30,000-word story in another three days.

The myth of Jekyll and Hyde's swift creation

Much of the creation of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is shrouded in hyperbole, myth-making, and unverifiable conjecture on the part of literary critics and scholars. The most persistent story is that of Jekyll and Hyde's preternaturally rapid composition. The commonly held belief is that the total time of composition for both the lost initial draft and the final version was a mere six days is, at best, questionable. What we can be certain of is that it was written and revised very rapidly, but more likely on the order of six weeks.

The three-day time frame would seem to come wholly from the recollection of Stevenson's son, Lloyd Osbourne, who, as quoted by Sir Graham Balfour in The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, wrote, "I don't believe that there was ever such a literary feat before as the writing of Dr Jekyll. I remember the first reading as though it were yesterday. Louis came downstairs in a fever; read nearly half the book aloud; and then, while we were still gasping, he was away again, and busy writing. I doubt if the first draft took so long as three days." Balfour, however, amends the three days per draft narrative, writing, "Of course, it must not be supposed that these three days represent all the time that Stevenson spent upon the story, for after this he was working hard for a month or six weeks in bringing it into its present form."

The misunderstood relationship between Jekyll and Hyde

The most misunderstood aspect of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is the dynamic between Jekyll and his monstrous alter ego. A century of pop culture reinterpretation onstage and in film has cast Jekyll and Hyde as two completely distinct personalities — one representing absolute virtue and good, the other abject depravity and evil. This popular and unshakable simplification is in conflict with Stevenson's intent.

As explained by Steven Padnick of TOR, there is no Mr. Hyde. While innumerable adaptations across a variety of media would have us believe that Dr. Jekyll's creation of Hyde is a consequence of disrupting the natural order, a terrible accident as it were, Hyde is, in fact, Jekyll's intended result. Dr. Henry Jekyll is no squeaky-clean servant of science bent on eradicating evil from the human condition. He's an aging and highly repressed man of the Victorian upper class desperate to indulge his prurient desires free of guilt and consequence. In effect, Edward Hyde is a chemically induced disguise.

As made clear in the text, Jekyll remains the dominant personality, always thinking of himself as Jekyll even while in the guise of Hyde. The doctor recalls his actions as Hyde using the pronoun "I," not "he," despite his claim that the diminutive, apelike brute is a separate entity with motivations all his own. Most tellingly, the novel's final chapter, titled "Henry Jekyll's Full Statement of the Case," is written by Jekyll while inhabiting the form of Hyde.

Jekyll and Hyde is a criticism of Victorian society

Robert Louis Stevenson's themes of duality and hidden self are not limited to the individual in Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The text also functions as a pointed critique of Victorian class roles and morality. Through a conscious doubling of characters, settings, and themes, Stevenson expertly exploits upper-class Victorian anxieties to drive his plot.

The London of Jekyll and Hyde is a city divided by class, in effect fractured along the same line as the Jekyll/Hyde persona. Henry Jekyll's London is a bastion of intellectualism, education, and wealth. Edward Hyde, however, is undoubtedly a denizen of the Soho district, which is marked by poverty, filth, and crime. As described by The University of Oxford's Great Writers Inspire website, Soho is "a slum area of the city that symbolises an atavistic playground, where immoral behaviour is expected and therefore much less noticeable." Never losing sight of the fact that Jekyll is Hyde, Stevenson skillfully smashes Victorian social fears, revealing that crime, corruption, and depravity also exist among the elite.

Stevenson's overarching critique of Victorian society lies in the author's assertion that Victorian morality, marked by a suppression of natural human impulses and the hiding away of the undesirable, was utterly destructive to both the individual and society.

A Freudian nightmare

As interpreted by Victorian audiences, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was a warning against the dangers of the libido unleashed, and this reading immediately influenced subsequent dramatic adaptations of the book. Although Stevenson leaves the specifics of Henry Jekyll and Edward Hyde's vices largely to the reader's imagination, the author balked at the sexual interpretation assigned to his work. In a private letter Stevenson wrote to New York Sun editor John Paul Bocock in 1887 regarding a popular stage adaptation of his book, the author stated, "[Hyde was] not, Great Gods! a mere voluptuary. There is no harm in voluptuaries; and none, with my hand on my heart and in the sight of God, none — no harm whatsoever in what prurient fools call 'immorality.' [...] people are so filled full of folly and inverted lust, that they think of nothing but sexuality."

Still, Stevenson's narrative continues to lend itself to a number of psychosexual readings, ranging from the broad interpretation as a statement on sexual repression in general to the more narrow analysis of the novel's subtext of duality as a gay metaphor. Regardless of interpretation, the novel's anticipation of Freudian psychology is undeniable, with the concepts of id, ego, and superego clearly illustrated by the Jekyll/Hyde schism.

You've probably been mispronouncing "Jekyll"

If your pronunciation of "Jekyll" rhymes with "speckle," you're one of the millions of people who have been saying the name of one literature's most iconic characters incorrectly. As explained by Daniel Evers of the University of Bristol on the website Interesting Literature, the proper pronunciation of the Scottish surname is "JEE-kul."

Stevenson borrowed the name from his good friend, famed British horticulturist Gertrude Jekyll. Commonly held conjecture states the Scottish author's choice of the surname "Jekyll," rhyming with "seek all" is a clever bit of wordplay intended to complement the name "Hyde," literally meaning "hide and seek."

In all likelihood, we have Hollywood, and specifically, American actor Spencer Tracy, to thank for the common mispronunciation. Tracy, who starred as Jekyll and Hyde in the popular 1941 MGM film adaptation directed by Victor Fleming, used the "Jeck-ul" pronunciation, and it stuck. Ironically, Fleming's film is a direct remake of Rouben Mamoulian's 1931 adaptation starring Fredric March in the title role(s). March uses Stevenson's preferred pronunciation of Jekyll throughout that film.

An eerie connection to Jack the Ripper

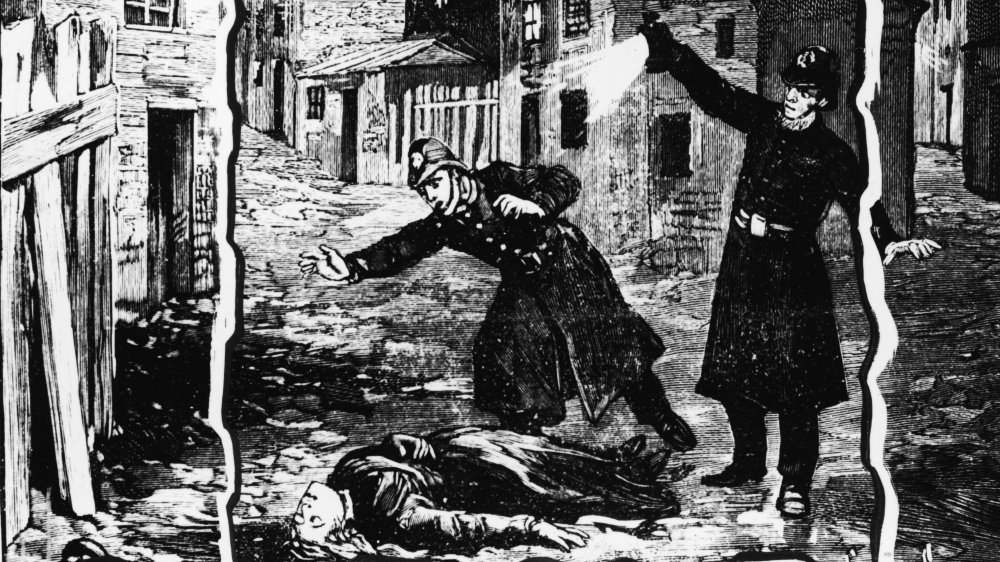

In the late summer and autumn of 1888, London's Whitechapel district was gripped by a series of brutal murders. The killer, dubbed Jack the Ripper, struck without warning or motive, leaving few clues in his bloody wake. Never definitely identified (theories of the Ripper's true identity captivate true crime buffs into the 21st century), Jack the Ripper seemed real-life Jekyll and Hyde, a comparison not lost on Victorian Londoners. As recounted in an article posted by the website of The British Library, the contemporary press often referred to the seemingly invisible killer as "Mr. Hyde."

In August 1888, the month of the first Ripper killing, Richard Mansfield took to the London stage in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The play was an instant hit, with audiences and critics especially praising Mansfield's performance as Edward Hyde. Distorting his features through stage lighting, the actor made his terrifying change in plain view of the audience. So complete was Mansfield's transformation into the play's diabolical villain that rumors swirled among theatergoers. On October 5, 1888, per The Vintage News, Scotland Yard received a letter claiming that Manfield was indeed Jack the Ripper. The actor, however, was never charged in the crimes. Mansfield, who died in 1907, went on to even greater success as an actor, eventually playing Jekyll/Hide on Broadway. His obituary in The New York Times declared him "the greatest actor of his hour, and one of the greatest of all time."

Jekyll and Hyde on film

From stage plays to comic books, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is one of the most adapted works of literature in history. Cinema has had a special fascination with Stevenson's tale, dating to the inception of the medium. According to the Robert Louis Stevenson Archive, in the silent era, 23 versions were produced before 1925, with a total of six made in 1920 alone.

Of the silent adaptations, the best is without a doubt John S. Robertson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Released in 1920, the film stars John Barrymore (pictured above) in one of the horror genre's defining performances in the dual role. F.W. Murnau, best remembered for 1922's Nosferatu, also adapted the novel for film in 1920. Titled Der Januskopf (The Head of Janus) Murnau's expressionist adaptation starring The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari's Conrad Veidt retains Stevenson's plot but changes the characters' names. Arguably the greatest Jekyll and Hyde film is MGM's definitive 1931 version from filmmaker Rouben Mamoulian. Starring Fredric March, Mamoulian's film is especially memorable for its grotesque interpretation of Hyde realized through the artistry of makeup pioneer Wally Westmore.

In the last six decades, Jekyll and Hyde has been subject to cinematic treatment ranging from the serious to the just plain weird, including a Blaxploitation version (Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde from 1976) and a dreadful 1982 parody that casts Hyde as a sex-crazed party animal (Jekyll and Hyde... Together Again) which, appropriately enough, ends with Robert Louis Stevenson rolling over in his grave.

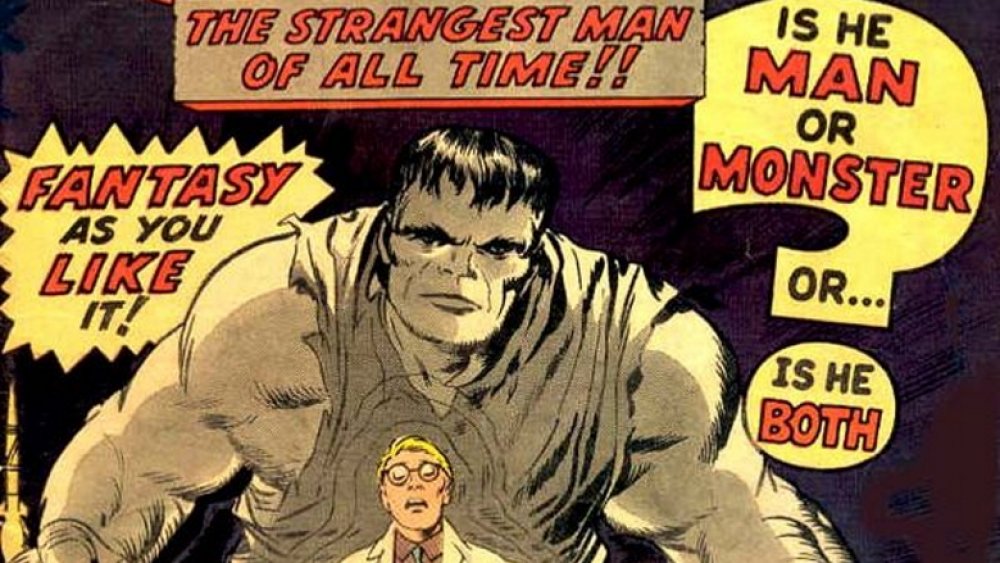

Jekyll and Hyde inspired a Marvel superhero

In the early 1960s, comic book legend Stan Lee, riding high on the surprise success of Fantastic Four, was growing weary of formulaic superheroes. Turning to his love of classic literature for inspiration, Lee would again revolutionize comics with his next creation. In a 2015 Rolling Stone interview, Lee elaborated on the genesis of one of Marvel's most enduring characters:

"I was getting tired of the normal superheroes and I was talking to my publisher. [...] I said, 'How about a good monster?' [...] I remembered Jekyll and Hyde, and the Frankenstein movie with Boris Karloff and it always seemed to me that the monster was really the good guy; he didn't want to hurt anybody, [...] So why not get a guy who looks like a monster and really doesn't want to cause any harm?" Fusing the tortured duality of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde with the pathos of Karloff's cinematic monster, the Hulk was another smash for Marvel.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was an early victim of media piracy

Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was a commercial and critical success and would go on to be Robert Louis Stevenson's most famous book, easily eclipsing his popular pirate tale Treasure Island. It was met with nearly universal acclaim in the contemporary press, and The Times of London praised it as Stevenson's best work, enthusiastically stating that "every connoisseur who reads the story must certainly read it twice."

Spurred on by the positive notices, sales figures for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were astonishing for its time. Selling 40,000 copies in England during its first six months of publication, it was just as successful across the Atlantic. According to Stevenson's biographer Graham Balfour, by 1901, over a quarter of a million copies were in circulation in North America. However, those sales did not necessarily translate into profits for the author. In a foreshadowing of the modern problem of media piracy, unauthorized editions were widely sold in the United States.