The History Of The Freemasons Finally Explained

Over the years, Freemasonry has become the stuff of legends as the line between fact and fiction blurs. With books such as The Lost Symbol and movies like National Treasure, Freemasonry has become associated with secrecy, intrigue, and of course, treasure. But in fact, historically, Freemasonry was ultimately nothing more than a boys club.

As a historically secret society, Freemasonry lends itself to rumors and conspiracies, especially since the true origin of Freemasonry is somewhat uncertain. Freemasons have built up a mythology for themselves that ties their lineage to King Solomon. And despite having no direct religious affiliation, Freemasons have also tied themselves to The Knights Templar, another historically secret society of Christian warrior-monks.

Despite the seemingly fabled existence of Freemasonry, the organization itself is very real and extant to this day. While many tales of Freemasonry influence have been overblown and hyperbolized, it cannot be denied that they created a worldwide community that was once remarkably widespread. This is the history of the Freemasons finally explained.

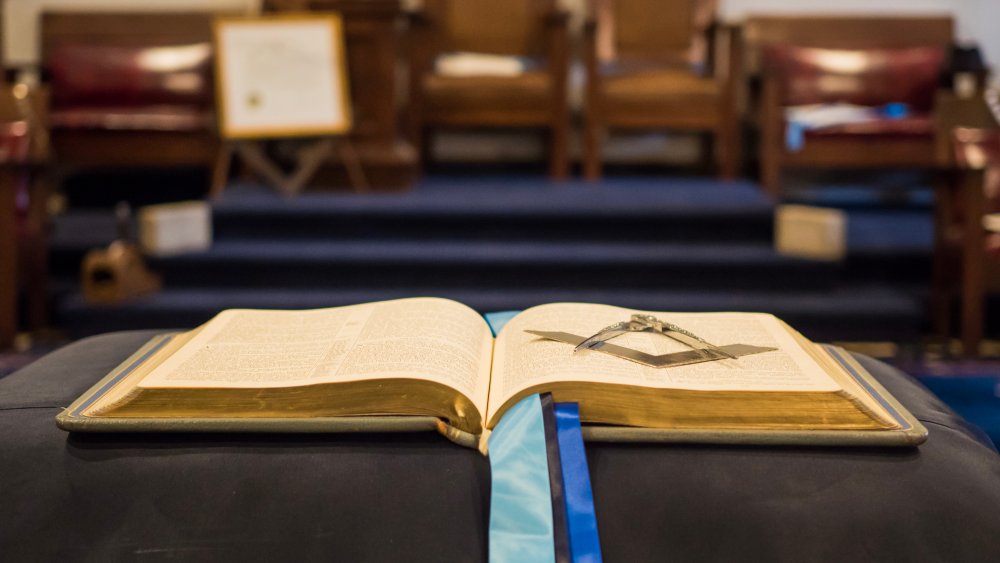

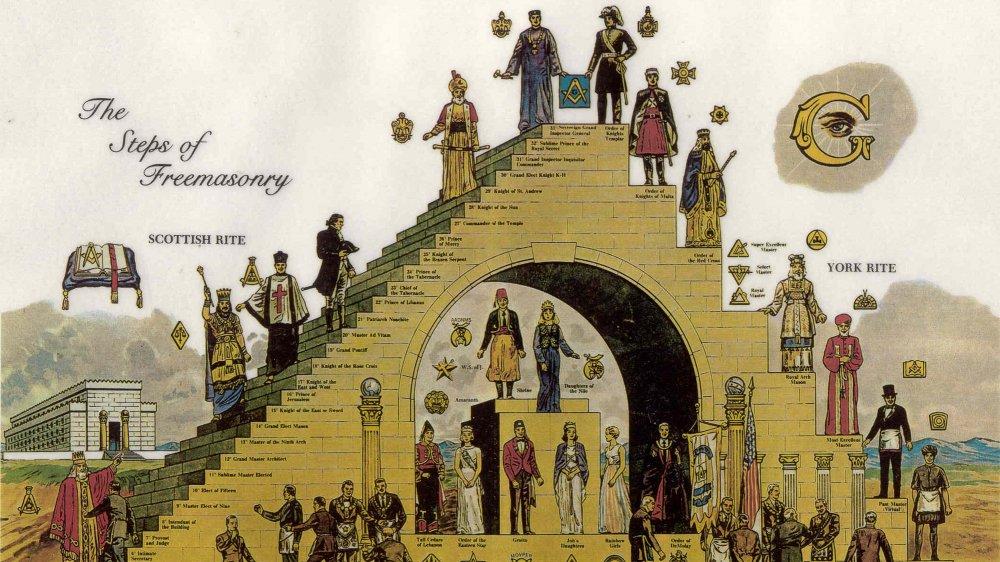

So what exactly do Freemasons believe?

While Freemasonry has the appearance of a religion, they are in fact a secular group, although they insist that people who join believe in an absolute being. As CBS reports, even though Freemasonry is not a religion, atheists and agnostics cannot join. For Freemasons, the belief in a supreme being is essential. Without the belief in a supreme, absolute being, they believe that there wouldn't be any obligation to be a good person, since they believe that God is what compels people to do good within their community.

According to the Masonic Service Association of North America, despite this required belief in God, Freemasons don't advocate for any particular practices or faiths. And despite requiring men to be of faith (women are not allowed to become Freemasons), religion is not allowed to be discussed during Masonic meetings.

Freemasons encourage charity, morality, and obedience to laws. Masonic principles are based on truth, relief, and brotherly love, from which charity, hope, and faith are derived. All these principles are supported by the pillars of strength, wisdom, and beauty, which provide the foundation from which all other principles are established. Ultimately, Freemasons are concerned with living a moral life, which they believe may be accomplished by living under the tenets of Freemasonry.

The craft of masonry

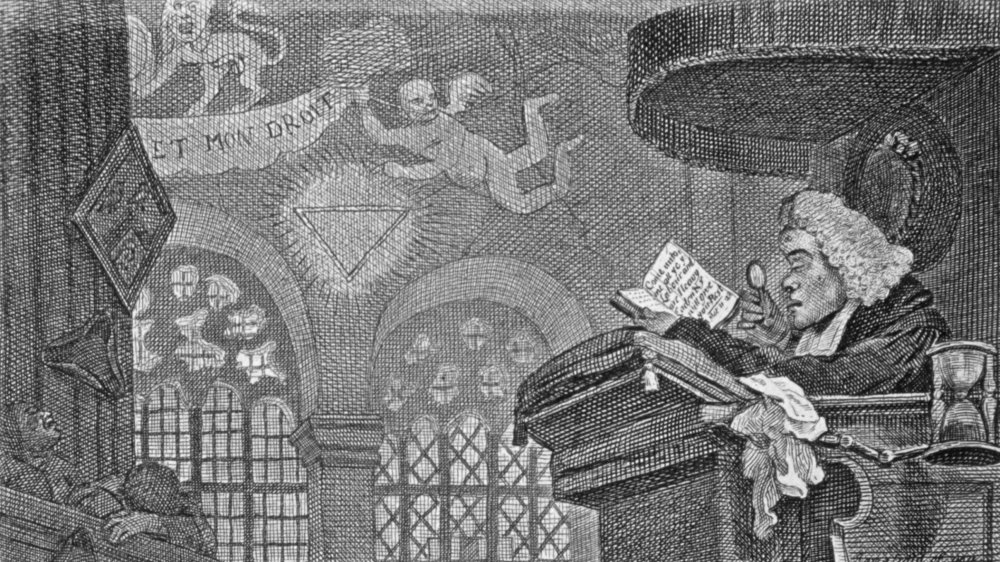

One of the earliest known masonic texts is the Regius Poem, also known as The Halliwell Manuscript. While the Regius Poem was previously known to scholars, its masonic connection was underlined by James Halliwell in 1838. According to the Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon, Halliwell and Reverend A.F.A. Woodford estimated that the manuscript was written in 1390, if not earlier.

The poem writes that "This honest craft of good masonry/ Was ordained and made in this manner/ Counterfeited of these clerks together/ At these lord's prayers they counterfeited geometry/ And gave it the name of masonry/ For the most honest craft of all." According to the Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry, the Regius poem attributes the invention of masonry to Euclid, who sought to provide some type of employment for the noble sons in Ancient Egypt. After masonry's invention by Euclid, it spread across the land, eventually arriving in England during the "time of Good King Athelstan's day" — approximately 924 AD.

Others, such as Chevalier Ramsay, have sought to attribute the origins of masonry to the Israelite people during the time of King Solomon, whose secrets were lost and then rediscovered and brought back by the Crusaders. At the time, and since, many have assumed that Ramsay was referring to the Knights Templar, though he gave them absolutely no mention.

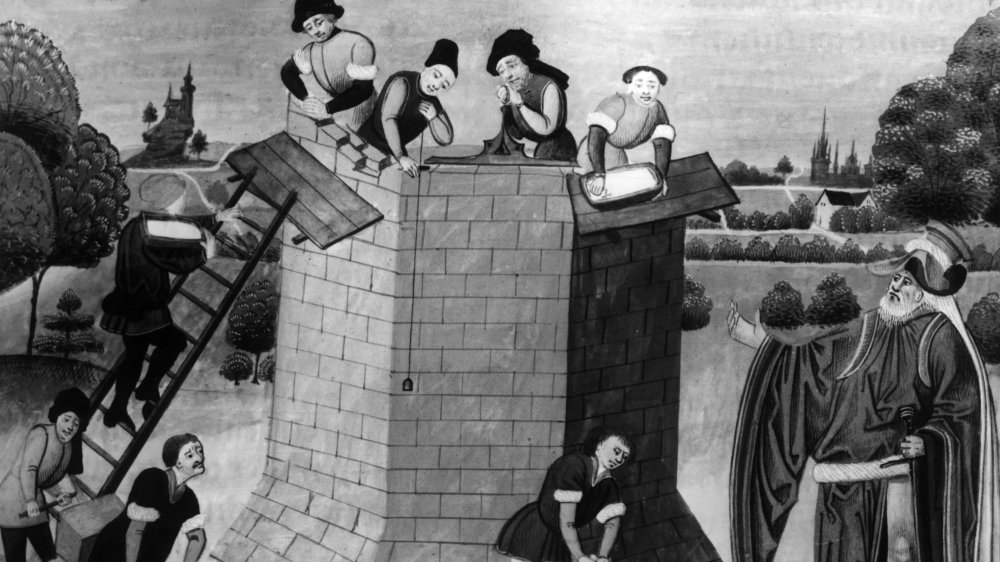

Medieval masons

While no one knows exactly when or how Freemasonry was really formed, the most widely accepted theory is that it evolved out of the guilds of cathedral builders and stonemason that arose during the Middle Ages. As cathedral building began to decline, some guilds and associations began to accept honorary members in order to boost their membership numbers. Modern Freemasonry lodges are considered to have developed out of these guilds. According to the Masonic Service Association of North America, the symbolism that is used in Freemasonry rituals is considered to have come from the medieval era.

In the Middle Ages, masons were expected to undertake a liberal education before becoming an architect, which established education as an integral part of masonry. According to the History Learning Site, in Medieval England, the guilds of stonemasons were sometimes called "Free Masons," since "free" stone was the name of the stone that the masons most often since it was soft and able to be intricately carved.

Disparate lodges across the British Isles

While Freemasonry is often associated with England, the first evidence of Masonic lodges appeared in Scotland. According to the BBC, by the late 1500s, multiple lodges were established across Scotland, ranging from Edinburgh to Perth. While it took until the next century for these guilds and lodges to set up an institutional structure — which many consider the beginning of modern Freemasonry — the lodges were well-established by that point.

Lodge Aitchison's Haven in East Lothian, also in Scotland, houses the oldest minutes in the world, dating to January 1599. In Edinburgh, Mary's Chapel is considered one of the oldest proven Masonic lodges in the world that is also still in existence, with recorded minutes dating back to 1599, though they started their record-keeping roughly six months after Lodge Aitchison's Haven. According to The Lodge of Edinburgh, once the Grand Lodge of Scotland was founded in 1736, Mary's Chapel promptly sent its representatives over, and the Grand Lodge promptly began compiling the minutes and records of all the official Scottish Masonic lodges. The number of total memberships over the years is estimated to be upwards of four million names in all.

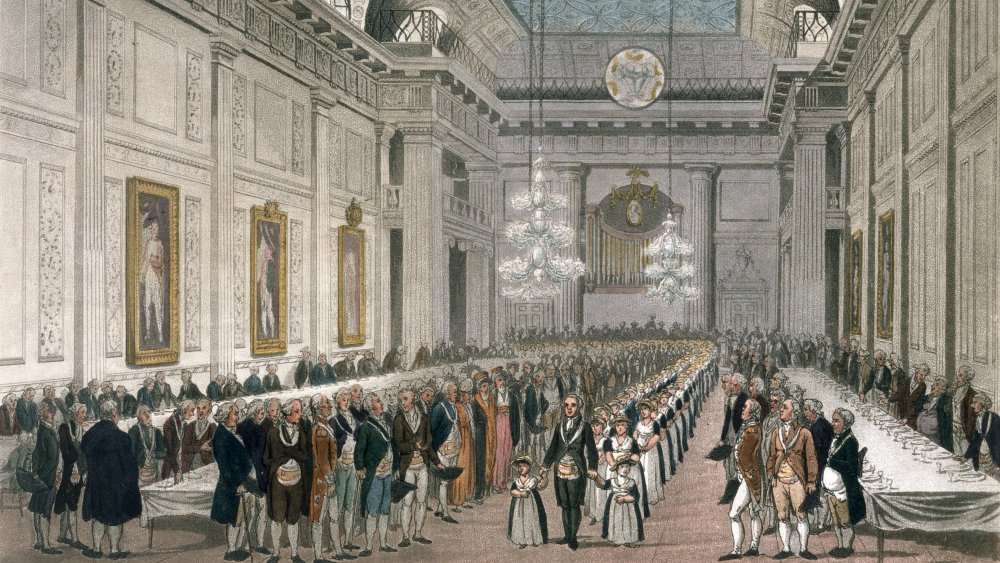

The Grand Lodge of England

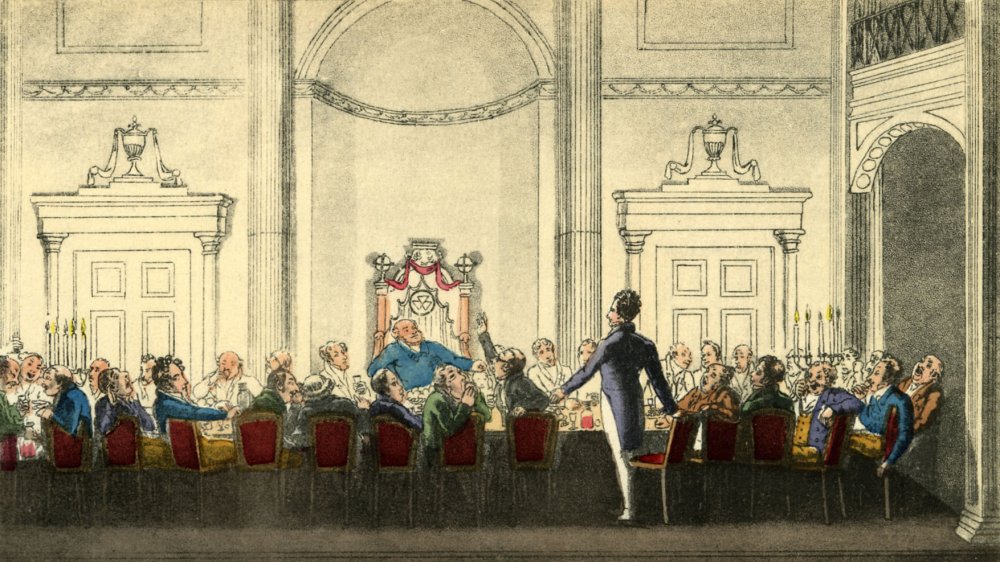

The official beginning of Freemasonry is considered to be June 24th, 1717, when four lodges in London joined together to create the Premier Grand Lodge of England. At the Goose and Gridiron alehouse in the churchyard of St Paul's, the four Lodges came together and established themselves as a Grand Lodge. Anthony Sayer was elected as the first Grand Master and was succeeded by George Payne.

According to Masonry Today, John Theophilus Desaguliers, a French-born British clergyman and natural philosopher, is credited with the Grand Lodge of England's success. Desaguliers was initially a member of Lodge No. 4, which was one of the original lodges to join together to form the Premier Grand Lodge of England. Desaguliers served as third Grand Master of the Premier Grand Lodge of England in 1719 after George Payne. After his retirement from Grand Master in 1720, he was appointed as the Deputy Grand Master three times.

Working with Scottish clergyman James Anderson, Desaguliers created the "Constitutions of Freemasons" in 1723, which is now known as Anderson's Constitutions. With this cooperative work, English Freemasonry ended up being especially influenced by Scottish precedents. According to the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Anderson's Constitution is considered a seminal work of Masonry, especially American Masonry, due to Benjamin Franklin's reproduction of Anderson's text within the American colonies in 1734.

Freemasonry spread across the Atlantic

Within 30 years, Grand Lodges had spread across the British Isles and across the Atlantic. According to the United Grand Lodge of England, the Grand Lodge of Ireland was established in 1725 and the Grand Lodge of Scotland was established in 1736.

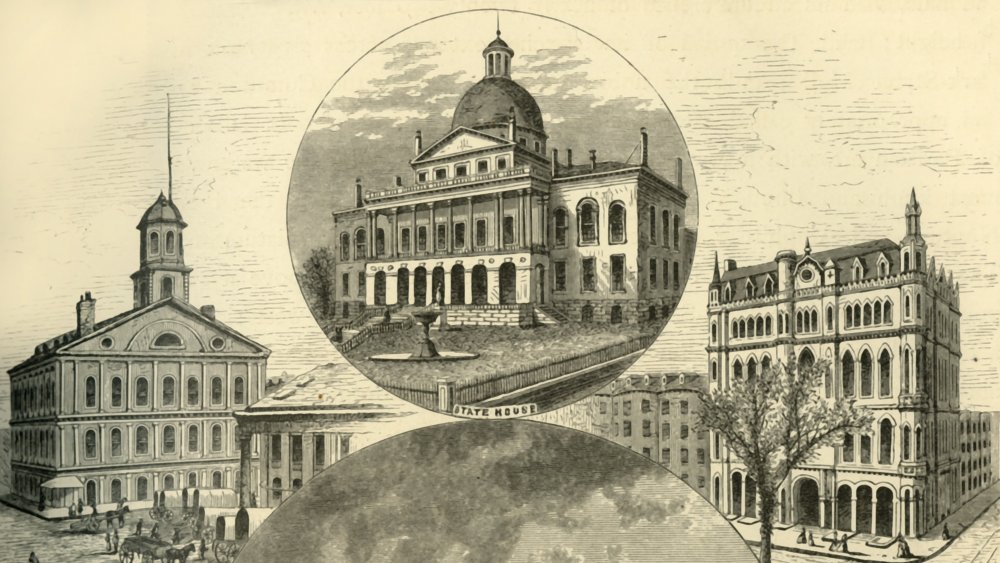

Freemasonry was also especially popular in the American colonies. According to JSTOR Daily, the first American Lodge was established in 1733 in Boston. Masonry may have had some influence on sentiment leading up to the American Revolution since the Freemasons were fundamentally opposed to claims of royalty. A number of the founding fathers, including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Paul Revere, and Joseph Warren were Freemasons themselves. Franklin even served as head of the brotherhood in Pennsylvania.

According to the Masonic Service Association of North America, during the 1700s, the Freemasons were responsible for the spread of Enlightenment ideals, including the liberty of the individual, the dignity of man, and the formation of democratic governments. And since education had been a hallmark of Masons since their inception, public education was also considered incredibly important to the Freemasons. The first public schools in both America and Europe were supported by the Freemasons.

Rift and reconciliation of the freemasons

In the 1750s, a rift occurred amongst English freemasons. According to the Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry, the split occurred due to the establishment of the Antients Grand Lodge in 1751 by the Freemason Laurence Dermott. The Antients claimed that, unlike the Premier Grand Lodge of 1717, they were the ones correctly following the ancient traditions of the Masonic Order. As a result, the Premier Grand Lodge was called 'the Moderns'.

According to the Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon, while John Morgan was the first Grand Secretary, he was succeeded by Dermott, who became the primary influence in the Antients Grand Lodge until his death in 1791. The two lodges antagonized each other for more than half a century until the creation of the United Grand Lodge in 1813, and according to Masonry Today, it's speculated that Dermott's death led to this reconciliation since he was the most outspoken antagonist of 'the Moderns'. The Unlawful Societies Act of 1799 might have also influenced the reconciliation, as it stated that people couldn't belong to a group that had secret oaths. This might have led the 'Antients' and the 'Moderns' to come back and work together in order to prevent the outlaw of Freemasonry. They were successfully able to incorporate an exception for Masons into the act.

The creation of the United Grand Lodge of England took four years of negotiations, and with the consolidation, a number of the rituals and procedures were also standardized.

The Morgan affair

Although William Morgan claimed to have been a Freemason, there's no record of him having had a Lodge membership. Morgan was a brick mason who lived in Batavia, New York from 1824 to 1826, and while he may not have been a Freemason himself, he claimed to have infiltrated the Freemasons.

On March 13th, 1826, Morgan signed a contract that outlined his intent to write and publish a book to 'expose' the secrets and procedures of Masonic rituals. Soon, Morgan was bragging to whoever would listen about his book, and many Freemasons feared that he would in fact reveal their closely guarded secrets.

In September 1826, Morgan was arrested for allegedly stealing a tie and a shirt. While he was acquitted of this crime, he was promptly rearrested due to a lack of payment towards a debt of $2.68. His debt was paid after just a day behind bars, and once more, he was released. However, this time he left the jail in a coach and taken to Fort Niagara, where he disappeared, never to be seen again.

According to Michigan State University, while Masonic organizations deny any involvement, many believe that Morgan was murdered in an effort to silence him. While 54 men were indicted for his disappearance, only 39 were tried in court and no one was convicted. When it was discovered that many of the jurors and the prosecutor were Freemasons, there was a public uproar of anti-Mason sentiments.

The decline and revival of American freemasonry

After the Morgan affair, there was a great deal of anti-Mason sentiment in America. Within three years, there were over 100 anti-Masonic newspapers being published in America, mostly in the north. Anti-Masonic political parties were also established, and in 1831 the Anti-Masonic Party ran former Freemason William Wirt for president. Wirt received 8% of the national vote.

According to "The Golden Age of Fraternalism" by Harriet W. McBride, active participation in Masonic activities and lodge membership began to drop drastically. The anti-Masonic movement wasn't only political. Anti-masons would force their way into lodges, deface buildings, and attack Freemasons in the street.

Leading up to the Civil War, many Anti-Masonic Party supporters turned their reforming impulse towards antislavery sentiments, while other Anti-Masonic politicians joined the Whig Party. According to JSTOR Daily, the anti-Mason backlash continued to grow until the Civil War, with abolitionists like John Brown campaigning against the Freemasons, who were often pro-slavery.

After the Civil War, since many considering the Masonic movement to have been extinguished, the anti-Masonic movement winded down. In response, the Masonic orders once more experienced a revival, becoming known as the 'Golden Age of Fraternalism'.

A continental split in freemasonry

Over on the European continent, tensions had been mounting between English and French Freemasons. According to the Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry, many French Freemasons came to Britain as refugees after Napoleon's coup in 1851. They were shocked at the English Freemason's relationship with the Anglican Church, which for them stood in stark contrast to the tenets of Freemasonry.

As tensions grew between The Grand Orient of France and the United Grand Lodge of England, the English and French masonic presses exchanged various barbs. The English Freemasons claimed that the French were too mystical, while the French Freemasons criticized the English for being preoccupied with their relationship with the church and cathedral building. The French encouraged them to consider "moral architecture" instead.

According to "U.S. Recognition of French Grand Lodges in the 1900s," by Paul M. Bessel, while American Grand Lodges had initially withdrawn their recognition of French Masonic Lodges in the 1800s, by the end of the century many recognized The Grand Orient of France as a legitimate lodge. Ultimately, the schism was never reconciled after The Grand Orient of France introduced the concept of Laïcité, which was intended to sever any relationship between Freemasons and organized religion.

Freemasons during World War I

Freemasonry is historically non-political, with some notable exceptions (such as the attempted invasion of Cuba in 1850). So, when World War I broke out, many Freemasons had to reconcile their involvement in a global war. During World War I, many Freemasons fought in the war while at home war-related charities were established to help raise funds.

In 1915, the Grand Lodge of England submitted an amendment that required all Freemasons of "German, Austrian, Hungarian, or Turkish birth to abstain from any Masonic meetings under English jurisdiction." According to Freemasonry Today, during the war, lodges with German ties such as Pilgrim Lodge, No 238, and Deutschland Lodge, No. 3315 completely ceased their meetings, while other lodges were disrupted as their members went to fight in the war.

According to the United Grand Lodge of England, after World War I, within three years, over 350 Lodges were newly established. Often, these Lodges were established by those who'd fought in the war and wished to continue the camaraderie they'd found during their service. A new headquarters was also established in London in memory of the Freemasons who'd lost their lives during the war.

Freemasons during World War II

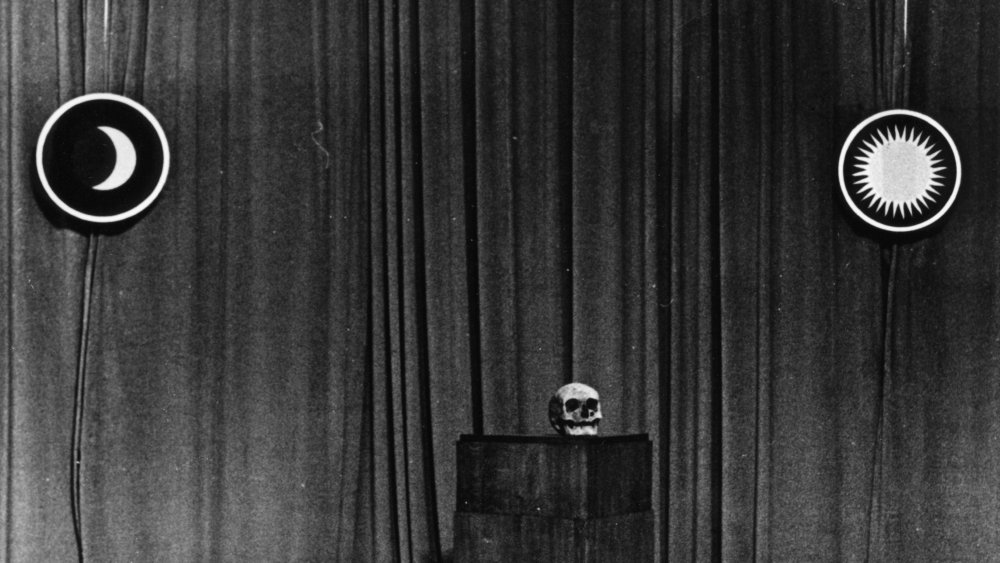

During World War II, the state of Freemasons became more precarious as the Nazis labeled them enemies of the German race. Per the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, in 1934 the Nazi Party ruled that Masons who had not left their lodges before January 30th, 1933 weren't allowed to join the Nazi Party. Soon after, Hermann Goering released a decree demanding lodges to voluntarily dissolve, provided that they submit a request for dissolution first.

The following year, Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick declared that Freemason lodges were "hostile to the state." On August 17th, 1935, Frick decreed that all lodges and branches must forfeit their assets to the state and dissolve. Nazi propaganda linked Freemasons with Jews and claimed that there was a "Jewish-Masonic" conspiracy. Despite this suppression, Freemasonry continued to exist, even to the point where Lodges are known to have existed within concentration camps, such as the Lodge Liberté Chérie, or the Beloved Liberty Lodge.

According to the United Grand Lodge of England, within three years after World War II, almost 600 Lodges were newly established, once more with the intention of continuing the camaraderie found during war-time service.

Freemasonry surviving if not thriving

While Freemasonry isn't as popular as it once was, with its membership steadily declining over the last century, in the 21st century there are almost six million registered Freemasons worldwide. According to NPR, in the United States of America, Freemason membership fell from 4.1 million in 1960 to 1.3 million in 2012.

According to the Atlantic, a lot of what Freemasons do now is simply spend time with one another, often hanging out at the lodge building every week. They support each other, engage in charitable work, and visit the widows of members.

The Freemasons are no longer as secretive as they once were since so much information is accessible online, but they have held onto some of their oldest traditions, such as only accepting men. Even though there are a few lodges in the United States that allow women to be initiated, they're not recognized as legitimate by traditional Freemasons.