Times Grant Lied To You

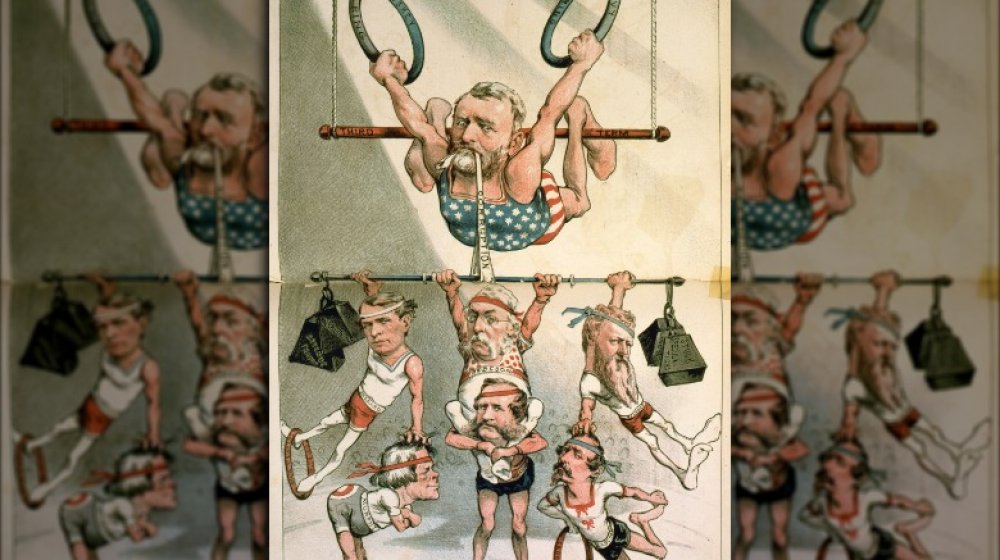

How much do you know about Ulysses S. Grant? According to HISTORY's three-part miniseries Grant, probably not much — the show's trailer describes Grant as a "forgotten" figure in American history, despite the fact that he commanded the Union army in the Civil War and served as America's 18th president.

The Leonardo DiCaprio-produced miniseries goes on to imply that, if you do happen to know something about Grant, it's probably that he was a drunkard, a "butcher" with no concern for human life, or a corrupt president. But Grant argues that the real Ulysses S. Grant was nothing like this popular image of him; instead, Grant was a doggedly determined hero with a rags-to-riches story that is the very personification of the American dream.

For the most part, Grant is a highly accurate show, relying heavily on the testimony of expert historians. But even so, the show gets some details wrong in its attempt to cram Ulysses S. Grant's entire life into three movie-length episodes. Even worse, in an effort to counteract the popular narrative of Grant as a corrupt drunkard, the show instead paints Grant as an all-around hero — ignoring some of the darker moments in the president's complex life.

The history of Ulysses S. Grant's name is complicated

One of the earliest scenes in Grant attempts to explain Ulysses S. Grant's mysterious middle initial. The show portrays the moment Grant arrived to his first day as a student at West Point in 1839, only to discover that he had been enrolled under the name "Ulysses S. Grant" — an error, as his real middle initial is "H." A stubborn official informs Grant that he must go by his registered name, and he nervously agrees.

This story is mostly true but leaves out the more complicated details of Grant's name. Grant was born Hiram Ulysses Grant, but he went by "Ulysses" from a young age. Then, when his father got their representative to nominate Ulysses Grant to West Point, the representative mistakenly registered him as "Ulysses S. Grant." But, unlike in Grant, the "S" didn't come out of nowhere. According to the New York Historical Society, the "S" actually originated from the maiden name of Grant's mother, Hannah Simpson Grant; the representative who registered Grant had thought that "Simpson" was part of his name, too.

When asked about the initial later in life, Grant would claim it stood for nothing. (No offense, mom.) Even so, the young Grant ultimately embraced the name. His new moniker "U.S. Grant" spawned a number of nicknames, as the show Grant explains. These included "United States" Grant, "Unconditional Surrender" Grant, and "Uncle Sam" Grant — the latter of which was shortened to Grant's most famous nickname, Sam.

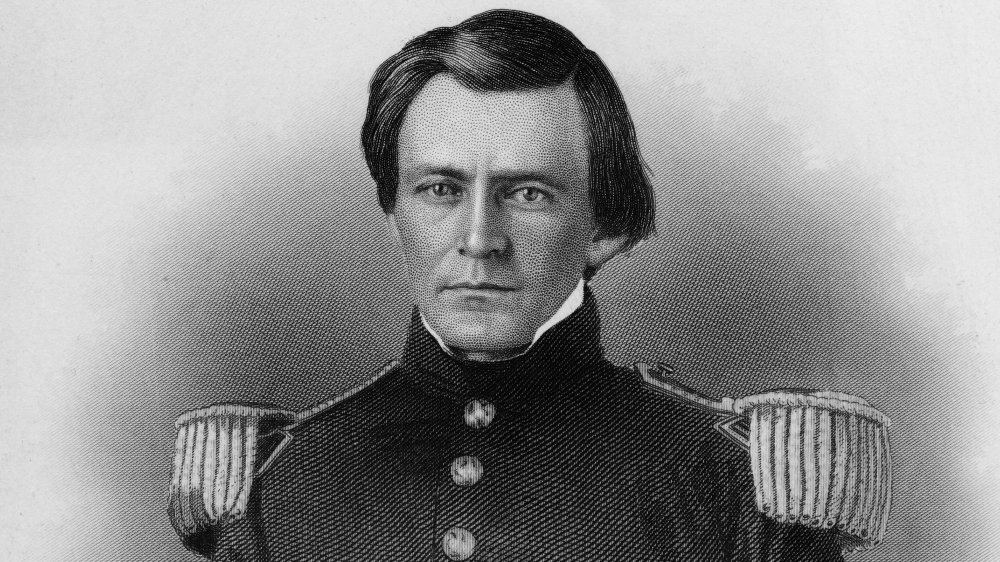

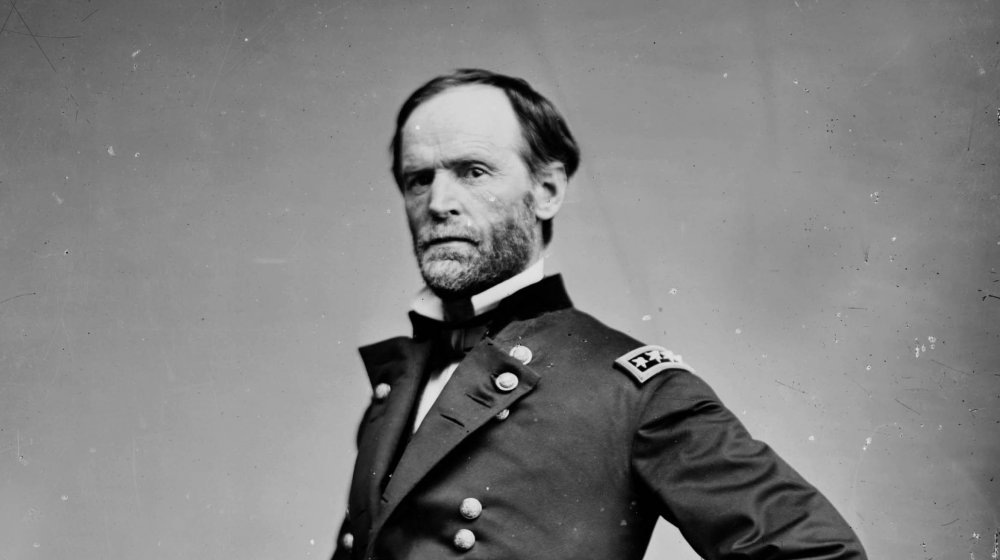

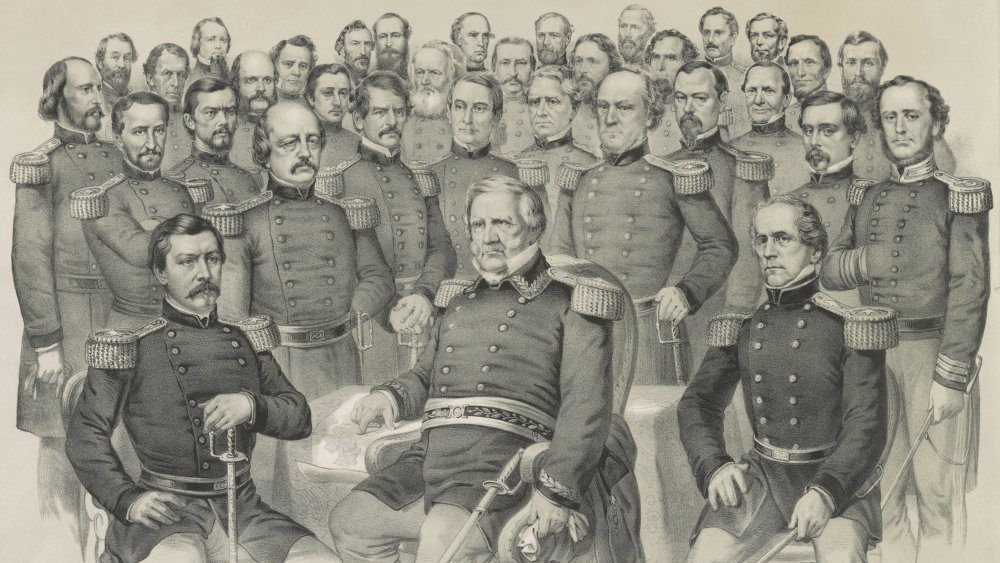

Grant didn't befriend William Tecumseh Sherman at West Point

Grant suggests that, while at West Point, Ulysses S. Grant formed a number of lasting friendships with men who would go on to become the leading military officers in the Civil War. In the registration scene, Grant is shown forming an immediate connection with two young cadets: James Longstreet and William Tecumseh Sherman. Longstreet would later become one of the Confederacy's most important generals. Sherman, on the other hand, is best known for his famous March to the Sea that crippled the Confederacy on behalf of the Union.

The first connection is true. Grant did indeed form a close friendship with the future Confederate general James Longstreet while at West Point. Some historians have even said that Longstreet served as the best man at Grant's wedding, but the National Park Service clarifies that this is not known for sure. Grant's closest friend at West Point was probably the future Union general Frederick Tracy Dent; Grant would even enter the Dent family when he married Frederick's sister, Julia, in 1848.

Grant, however, fabricates a connection between William Tecumseh Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant. While the two men would go on to become key partners during the Civil War, there is no evidence that they were close during their West Point days. Sherman graduated from West Point in 1840, while Grant graduated in 1843, and there seems to be no record of the two men interacting during their time at the academy.

Grant may not have resigned from the army due to alcoholism

Grant does a fairly good job of showing Ulysses S. Grant's troubling relationship with alcohol. Grant struggled with alcoholism throughout his life; at the same time, descriptions of Grant's alcoholism were often overblown in the press and by his political enemies. While, today, President Grant is remembered as a drunk, the true story is more complicated.

One particularly difficult incident in Grant's life occurred during his year stationed at Fort Humboldt in 1854. By the time Grant had arrived at the California fort, he had been separated from his family — including a toddler and a newborn son — for many months. As the months at the Fort continued, Grant felt increasingly isolated. As a result, he turned to alcohol as a means of self-medication. According to biographer Ron Chernow, following one of his binges, Grant was told by a commanding officer to "resign or reform." And it's on record that Grant resigned from the army soon after. So, it would be natural to assume that Grant's decision to resign from the army was the direct result of his failure to sober up — and Grant heavily implies this.

But, in reality, we simply don't know that for sure. Grant would later say that "the vice of intemperance had not a little to do with my decision to resign," and the War Department would report that "Nothing stands against [Grant's] good name." So, Grant's implication that drunkenness directly led to Grant's resignation is flimsy at best.

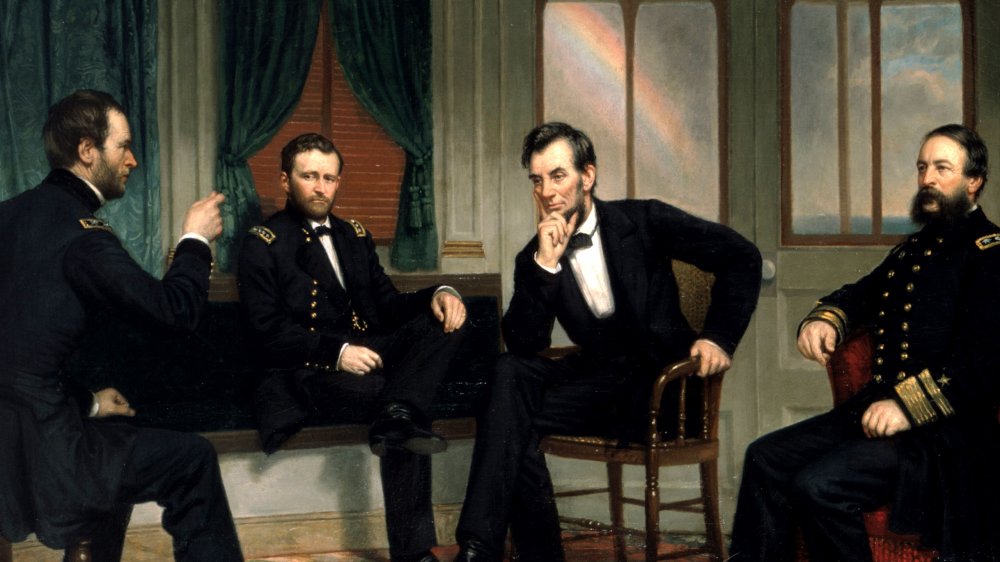

Grant wasn't always a big fan of Abraham Lincoln

After watching Grant, you'd probably have the impression that Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln had a relationship of mutual respect from the moment the two men learned about each other. But this is not the case; Grant was not always a supporter of President Lincoln.

According to biographer William McFeely, in the 1860 election (which Abraham Lincoln would ultimately win), Grant actually favored the Democrat candidate Stephen A. Douglas over the Republican, Lincoln. Among other things, Grant feared that electing a Republican candidate would lead to increased tensions with the South. And, in fact, Grant was right; Lincoln's election was one of the major catalysts for the Civil War which began in 1861. Besides that, Grant's wife Julia was a committed Democrat from a slave-owning family, so Grant was willing to overlook that most Democrats defended slavery at the time.

When Grant later became a key figure in the Republican party, he would attempt to do some damage control, covering up his initial lack of loyalty to Lincoln. Grant would emphasize that he favored Abraham Lincoln over the more popular of the two Democrat candidates, John C. Breckinridge. While technically true, this omits that Douglas was his preferred candidate all along.

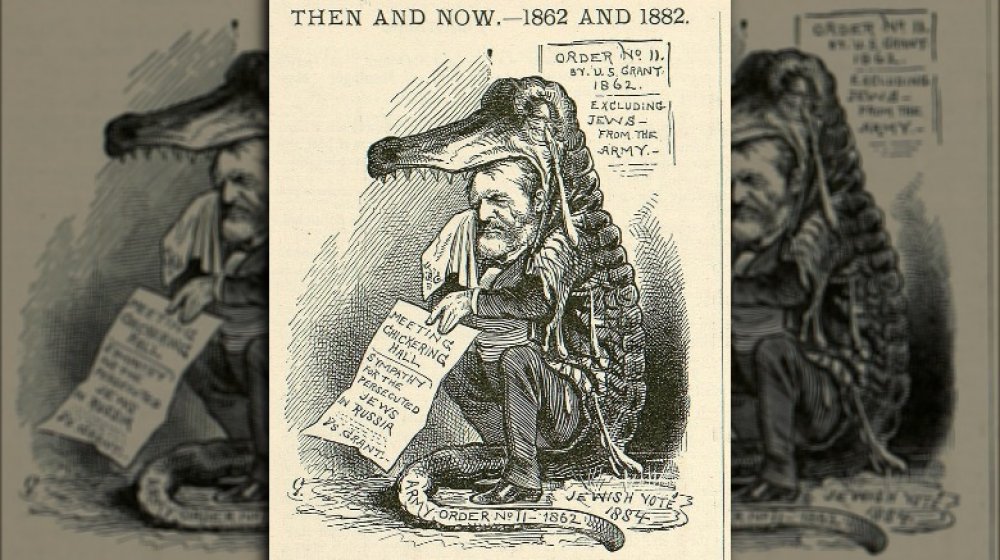

The show ignores an anti-Semitic decree Grant passed

Grant does a good job of depicting Ulysses S. Grant's complicated, but eventually positive, relationship with the African American community — from his marriage into a slave-owning family to his later commitment to Reconstruction and the defeat of the first Ku Klux Klan. But Grant completely ignores Grant's tumultuous relationship with another group: Jewish Americans.

By 1862, General Grant's men had claimed large swaths of Confederate territory. But Grant was dismayed to find that an illegal cotton trade ran rampant throughout the region, allowing Southern plantation owners to continue to profit by having their cotton smuggled to the North. Grant knew that, as long as this trade persisted, the South would be able to strengthen itself financially. Furthermore, General Grant came to believe — as he would explain in a letter — that the trade was being run "mostly by Jews and other unprincipled traders." So, on December 17th, he issued General Order No. 11, which expelled "Jews, as a class," from the land he controlled in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky. All Jewish people were forced to evacuate their homes within 24 hours; historian Bertram Korn calls it "the most sweeping anti-Jewish regulation in all of American history."

It should be said that Grant later attempted to atone for this anti-Semitic order; according to the Atlantic, he would go on to appoint a record number of Jews to public offices during his presidency. Grant publicly apologized for the order, but nonetheless, continued to be haunted by his failure to live up to the promises of the Constitution.

The Union army had success in the East before Grant took command

To make Ulysses S. Grant look more heroic, Grant makes it seem that the Union was a complete military failure in the Eastern Theater of the war until President Lincoln personally selected Grant to take over. The show emphasizes how disappointed Lincoln was with all generals — that is, until he found Ulysses S. Grant, a man he could rely on.

It's true that Lincoln had a tumultuous relationship with much of the Union army leadership, regularly removing commanding generals in favor of new ones. But it's false to suggest that Grant was the only effective general that the Union ever had. Before Grant came along, there had already been a number of noteworthy Union successes in the Eastern Theater. For example, Union General George McClellan halted the Confederate invasion of Maryland at the bloody Battle of Antietam in 1862. Later, General Meade was able to defeat the advancing Confederates at the famous Battle of Gettysburg — the Civil War's bloodiest battle. For this feat, Lincoln would write an unsent letter thanking General Meade for his "magnificent success," but criticizing him for his failure to pursue the Confederate army after they retreated.

Thus, to his credit, Ulysses S. Grant was indeed the general who delivered the death blow to General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia — a feat no other Union general had been able to accomplish.

The show gives an unrealistic portrayal of death in the Civil War

If you pay close attention to the battle scenes in Grant, you'll notice that the vast majority of the show's soldiers die in one of two ways. First, many soldiers are shown being hit by a bullet to the head. Second, other soldiers are shown being killed in brutal hand-to-hand combat by bayonets, blunt objects, or even strangulation.

As it turns out, neither of these causes of death were particularly common during the Civil War. As for the second, historian Jonathan Steplyk explains that "close-quarters melees were quite literally exceptional incidents, occurring relatively rarely in Civil War combat." Historian D. Scott Hartwig agrees, critiquing popular depictions of the Battle of Gettysburg for their over-reliance on hand-to-hand fighting. While hand-to-hand combat did occur, it was probably far less common than Grant would have you believe.

Likewise, Grant gives the false impression that the young farmers and toolsmiths who enlisted in the Civil War all had sniper-level accuracy, instantly killing their enemies with a well-placed bullet to the brain from yards away. In reality, bullet fire during the Civil War was highly inaccurate, often striking limbs or other body parts; as a result, amputation was "the most common Civil War surgery," according to the Ohio State University. Furthermore, disease was the number one cause of death during the Civil War, often resulting from infected wounds; few men were lucky enough to be given the instantaneous death you see in Grant.

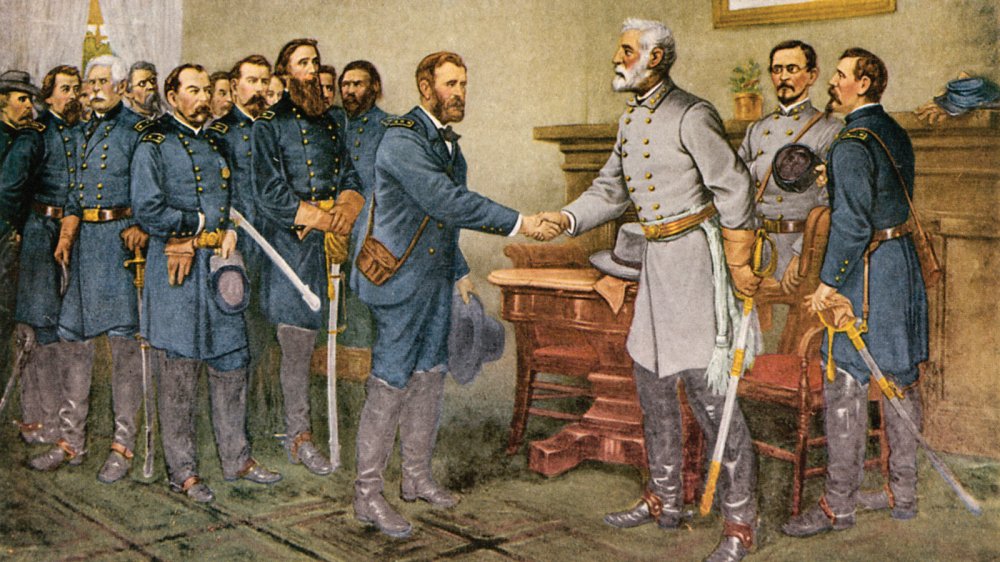

General Lee's surrender to Grant was probably friendlier than in the show

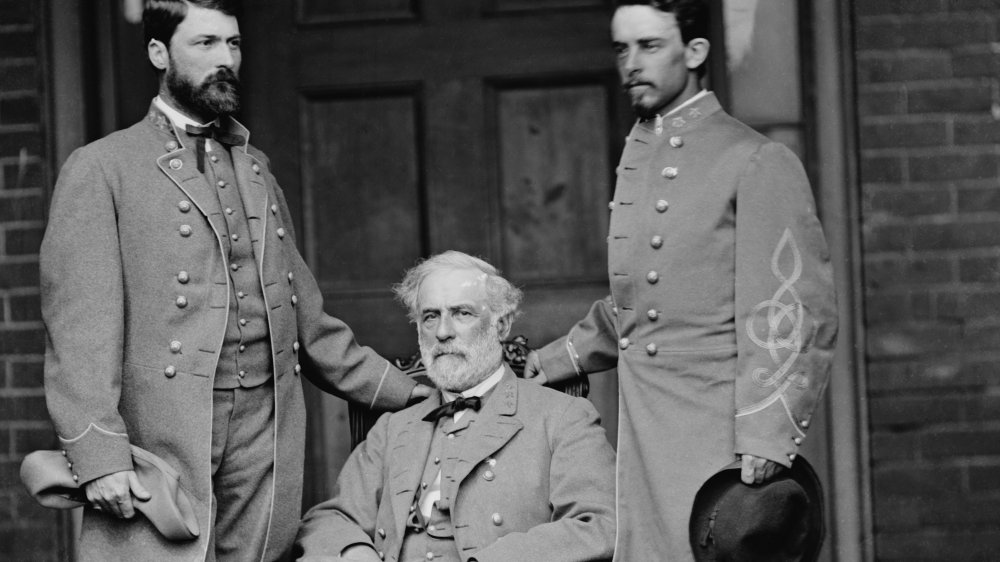

Grant argues that the popular image of Grant as a corrupt drunkard makes the man look far worse than he really was. On the other hand, Grant recognizes that the popular narrative around Confederate General Robert E. Lee has had the reverse effect, turning him into a fearless, if misguided, leader. So, to tear down this narrative, Grant instead portrays General Lee as a prideful coward; Lee is hardly able to maintain eye contact with Grant during his surrender at Appomattox.

While it is true that Lee is no hero, Grant likely overstated the overall tension surrounding his surrender. Lee was not happy to have to surrender, of course, overdramatically saying he would "rather die a thousand deaths" than go see General Grant. But, when the two men did come together at Appomattox, most sources agree that the meeting was friendly.

According to the Civil War Monitor, General Grant sought to avoid embarrassing General Lee and began the meeting by mentioning that the two men had already met many years ago during the Mexican-American war. Lee replied that he remembered Grant from that war, according to the National Park Service, and the two men conversed "in a very cordial manner, for approximately 25 minutes." (In Grant, General Lee remarks that he has no memory of Grant from the war.) When Lee turned the conversation to the terms of surrender, he was satisfied with the terms Grant put forward.

Lee's surrender at Appomattox did not mark the end of the Civil War

Many documentaries about the Civil War give the false notion that General Lee's surrender to General Grant at Appomattox marked the definitive end of the Civil War. Grant unfortunately borrows this inaccurate cliché. While it makes for a much simpler narrative to say that General Lee's surrender was the final moment of the Civil War, the truth is much more complicated; in reality, Lee's surrender was only the beginning of the end.

In reality, there were numerous Confederate "armies" that were active during the Civil War. Robert E. Lee only commanded one of them, the Army of Northern Virginia. As a result, there were still a number of battles that took place after Lee surrendered on April 9th, 1865. According to History.com, mid-April saw battles between Union and Confederate forces in North Carolina and Georgia, while fighting concluded in May with final skirmishes in South Carolina and Texas. The University of Richmond explains that the Battle of Palmito Ranch, Texas, is generally considered the final armed conflict of the Civil War; it concluded on May 13th, 1865. Interestingly, the Confederates won that battle, but it was a bittersweet victory, as it was already clear that the Confederacy had no future.

But even so, according to History.com, it was not until August 20th, 1866 that President Andrew Johnson declared a formal end to the Civil War.

The show omits many aspects of Grant's presidency

Of Grant's four-and-a-half-hour running time, less than 20 minutes are dedicated to Ulysses S. Grant's eight-year presidency. The decision to focus on Grant's military career rather than his political one is more of a stylistic choice than an overt flaw, but for any history fan who wants to learn more about Grant as a president, Grant is not the show to watch.

And this is unfortunate, as the often-ignored Grant administration was characterized by many fascinating successes and failures. For example, as the University of Virginia explains, President Grant attempted to annex the Caribbean country of Santo Domingo — now referred to as the Dominican Republic. Grant believed that the island could be a great refuge for freed Blacks facing violence, and an American survey even found that many Dominicans favored annexation. The proposal ultimately fell through, as the Senate defeated the treaty in 1870.

Besides that, did you know that Ulysses S. Grant was the youngest president elected at the time, at age 46? Or that he founded America's first National Park, Yellowstone? How about the fact that he was one of the first presidents to express subtle support for women's suffrage? If Grant truly wanted to depict the complicated life of Ulysses S. Grant in a well-rounded way, it would have dedicated more time to these stories.

The show ignores many of the scandals that plagued Grant's administration

Of the many noteworthy events of Grant's presidency, perhaps the biggest trend that Grant overlooks is the large number of scandals that the Grant administration faced. Grant does discuss one — the Whiskey Ring scandal — and proves that President Grant was innocent; he was simply too loyal to the corrupt men in his administration and sullied his own good name in the process. After watching Grant, you'd probably wonder why he was ever considered corrupt in the first place.

But Grant ignores the fact that the Whiskey Ring scandal was just one of many that the Grant administration faced. In 1869, there was the "Black Friday" scandal, where two investors attempted to use insider information to corner the gold market. Then there was the Crédit Mobilier scandal which came to light in 1872; government officials were found to have taken bribes from railroad companies, giving those companies massive contracts in return. Finally, there was the Belknap scandal in 1876, where Grant's Secretary of War helped trading companies obtain illegal monopolies on trade in Native American territories in return for a cut of the profits.

By all accounts, President Grant did not personally profit from these scandals; he appointed many of those responsible for corruption, but there is no evidence that he was corrupt himself. Even so, learning about the sheer number of scandals that he faced is critical to understanding the reputation of his presidency. And so, Grant was unwise to overlook them.