Things 42 Didn't Tell You About Jackie Robinson

In just the third film appearance of his career, Chadwick Boseman portrayed Jackie Robinson in a biopic about the famed activist and Baseball Hall of Famer. Surrounded by an all-star cast that included Harrison Ford as Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, André Holland as famed African American sportswriter Wendell Smith, and Christopher Meloni as Dodgers manager Leo Durocher, 42 was both a critical and commercial success and became the springboard for Boseman's career as a leading man in Hollywood.

Like any biopic, certain details were altered or glossed over to focus on the main story of Robinson integrating Major League Baseball. This is in spite of the fact that Robinson's widow, Rachel Robinson, assisted in the production. Rachel described the film to Fox Sports as "very authentic" and said, "I love the movie. I'm pleased with it. It's authentic and it's also very powerful."

Jackie Robinson's story was a real-life epic, meaning that a number of details could not be squeezed into two hours of run time.

Jackie Robinson's pre-Dodgers life

Because 42's primary focus is on Jackie Robinson's first year with the Brooklyn Dodgers, much of his pre-baseball life is left untouched. The best the movie offers is the implication that Robinson had an absent father.

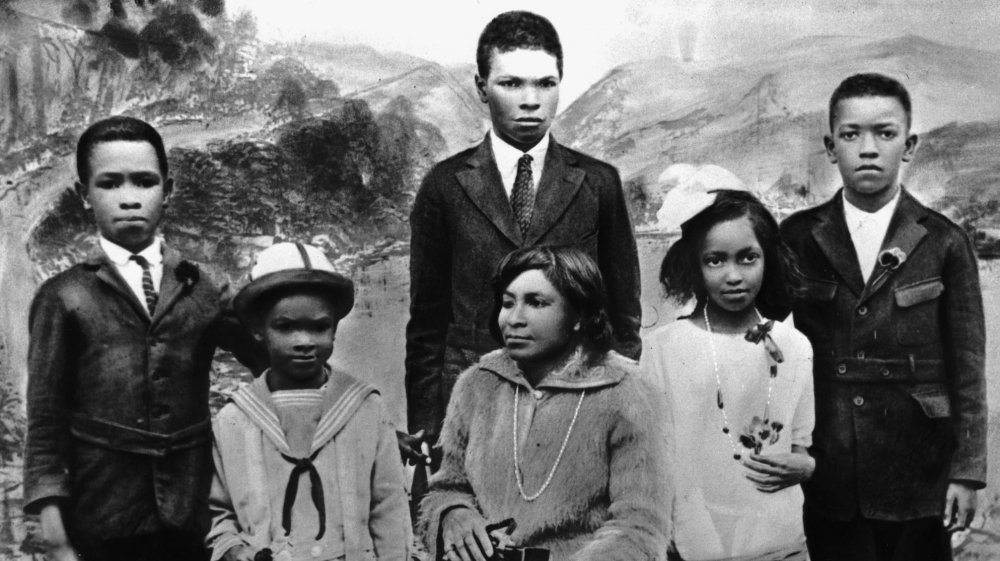

According to his website, this detail of Robinson's life was true. The future baseball star was born Jack Roosevelt Robinson in Cairo, Georgia, in 1919. An ESPN documentary on Robinson said that his father left the family a year after Jackie's birth. Jackie's mother, Mallie Robinson, took her children and moved to Pasadena, California, soon afterward. Arnold Rampersad said in the documentary that Mallie was the "central influence" of Jackie's life, teaching him "restraint and optimism in the face of adversity." As the only Black family in the neighborhood, they stood firm against white neighbors who tried to force them out.

At UCLA, Robinson became the first collegiate athlete to win varsity letters in four sports: baseball, football, basketball, and track. In 1941, his football talents earned him All-American honors. However, financial troubles forced Robinson to drop out of university, and within five months, he was a member of the United States Armed Forces.

More than ten years before Rosa Parks, Robinson's civil activism was put on display when he was court-martialed for refusing to leave his seat on a bus. Robinson won his court-martial and was honorably discharged in November 1944. He joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League in 1945, which is where the movie begins.

The end of the Negro Leagues

According to the Negro League Baseball Museum, the late 1800s saw many African Americans play baseball in leagues and barnstorming tours. Moses Fleetwood Walker and Bud Fowler were some of the first African Americans in professional baseball. However, an effort grew within the early professional leagues to push out their Black players, and by the turn of the century, the color barrier was unofficially established, keeping African Americans out of the sport.

Multiple attempts were made at the beginning of the 20th century to create a Black baseball league. According to Britannica, it was not until 1920, under the leadership of Andrew "Rube" Foster, that the first viable Black league was formed. The league's popularity grew over the next two decades. However, with mounting pressure from news writers in African American and Communist circles to end the color line in Major League Baseball during the late 1930s and early '40s, Jackie Robinson was finally signed in 1945, as recalled by famed Negro League player and manager Buck O'Neil.

Unfortunately, Robinson's signing marked the beginning of the end of the Negro League. J.L. Wilkinson, the owner of the Kansas City Monarchs, sold the team the next year, as he saw the writing on the wall, MLB.com reports. Major League teams started to sign Negro League players to their teams, taking Negro League fans along with them. By the early 1960s, both the American and National Negro Leagues were forced to disband for financial reasons.

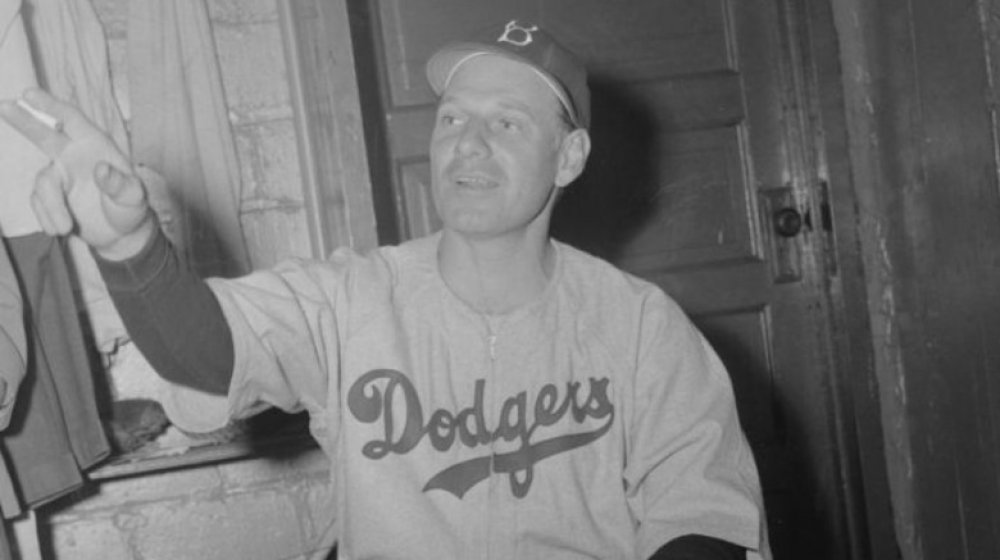

Leo Durocher post-suspension

Law and Order star Christopher Meloni's portrayal of manager Leo Durocher was a standout performance in 42. Durocher, as in real life, was the Dodgers' manager who quickly quashed any ideas of boycotting games from a number of Dodgers players who did not want to play with Robinson.

Durocher won two World Series with the 1928 New York Yankees and the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals as a player. While an average player at best, Durocher's best skill was as a team leader. According to his Baseball Hall of Fame bio, Durocher was nicknamed "The All-American Out" by teammate Babe Ruth. Also nicknamed "The Lip," Durocher was hired as a player-manager for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1939, and by 1941, the team had won the National League pennant.

During spring training in 1947, before Robinson made his debut with the Dodgers, Durocher was suspended for a year by Commissioner Happy Chandler for his "accumulation of unpleasant incidents," which included associations with gamblers and, portrayed in the film as the leading reason, his relationship with actress Laraine Day.

After the suspension, Durocher was hired by the New York Giants, where he mentored another Negro League star, Willie Mays. ESPN and Bleacher Report both argue that Mays is the greatest player in baseball history. According to Baseball History, Durocher helped guide Mays early in his career, even having to console a crying Mays when the young player was struggling. Mays said Durocher "was like my father away from home."

HUAC used Jackie Robinson to slander Paul Robeson

In 1949, at the height of the "Red Scare," the US House of Representatives' House Un-American Activities Committee, or HUAC, looked to expose any communist citizens in the country. The Committee pressured Jackie Robinson to testify during a hearing to rebuke African American actor and musician Paul Robeson (pictured above).

Like Robinson, Robeson was a star football player while in college and broke into a popular industry at the center of American life. Unlike Robinson, who, according to Undefeated, was a conservative integrationist politically, Robeson was much bolder in discussing American racism. This came to a head in 1949 when Robeson was misquoted during the Soviet-funded World Peace Conference in Paris as saying that it was "unthinkable that American Negros would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against the Soviet Union."

As Time reports, once the "quote" appeared in newspapers, Robeson's career took a hit. His music was banned, and his passport was revoked, limiting his ability to tour. Civil rights organizations quickly denounced Robeson and Robinson, who was being pressured to testify on behalf of the African American community and now had little choice. Robinson's testimony had little to do with Robeson's comments, simply saying that one man could not speak for a whole race, and focused more on the fight against racism. Still, Robinson would regret his testimony against the blacklisted Robeson, who, according to Boundary Stones, had led a delegation in 1943 that met with baseball owners and the commissioner to integrate professional baseball.

Other teams tried to prevent Jackie Robinson from playing

Jackie Robison's entrance into the sport was not taken lying down, and attempts were made to push him out. 42 did show a few of Robinson's Brooklyn teammates attempting to boycott Robinson off the team and Philadelphia Phillies general manager Herb Pennock pressuring Branch Rickey to sit out Robinson when playing in Philadelphia. The film did not, however, show the attempts made by Robinson's opponents to oust him from the sport.

ESPN's documentary on Robinson says that MLB commissioner Happy Chandler, at the same time he was suspending Dodgers coach and Robinson supporter Leo Durocher, intervened when he heard rumors that the Chicago Cubs were going to boycott. The Cubs fell in line and ended their boycott. Another team that planned to boycott Robinson were the defending champions the St. Louis Cardinals. According to Buzzy Bavasi, a Dodgers executive from 1940 to 1968, National League president Ford Frick was made aware of three Cardinal players who refused to get on the field with Robinson and said this: "Gentlemen, I understand you don't want to play today. If you don't play today, you will never play baseball again. Not as long as I'm president of the league, and I just signed a seven-year contract today."

The strike was quickly quashed. However, SABR reports that Frick never made this or any threat to the Cardinals, contradicting Bavasi. Years later, Cardinals first baseman Dick Sisler did confirm that players on the team were planning to boycott Robinson.

Jackie Robinson's relationship with his son

The only child of Jackie and Rachel Robinson to appear in the film was their eldest son, Jackie Robinson Jr. Jackie and Rachel Robinson would go on to have two more children: Sharon Robinson (b. 1950) and David Robinson (b. 1952). During his life, Jackie Jr. and his father had a strained relationship, and, tragically, Jackie Sr. would outlive his son.

Jackie Robinson Jr. was born on November 9, 1946, around five months before his father made his Dodgers debut. According to Sportscasting, the eldest Robinson had a difficult childhood, dealing with a myriad of emotional issues and having to be enrolled in special education. Robinson Jr. dropped out of high school during his senior year and, like his father, joined the US Army, desiring to find a stable environment. The teenage Robinson would not find this in the chaos of the Vietnam War, though. In 1965, after three years in the Army, Jackie Jr. was injured while attempting to rescue a fellow soldier. Jackie Jr. returned home addicted to drugs.

The New York Times reported that Jackie Jr. spent two years at Daytop, Inc., in Seymour, Connecticut, recovering from his addiction. The rehabilitation was successful, and soon, he became the assistant regional director of the facility. Just as it seemed that his life had turned around, now mentoring individuals like himself, Jackie Robinson Jr. died on June 17, 1971, in a car accident while driving to his parents' home in Stamford. He was 24 years old.

Jackie Robinson's Relationship with other Black athletes

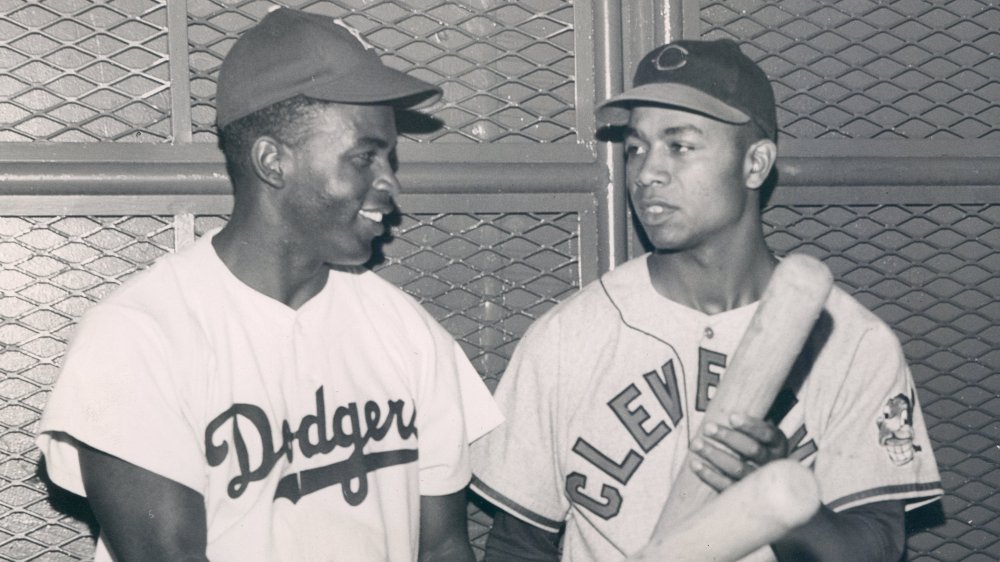

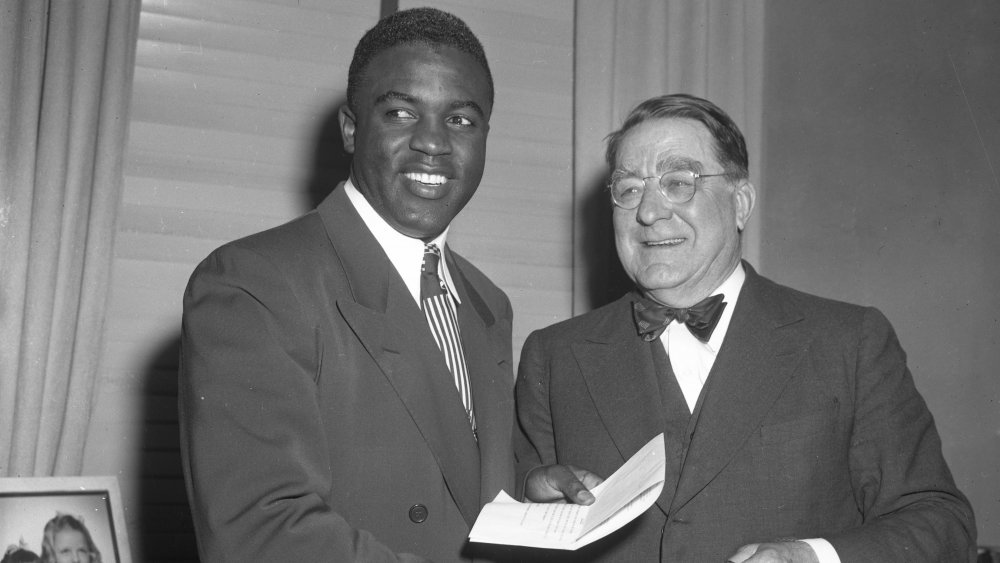

It wasn't long after Jackie Robinson played his first games with the Dodgers that other organizations began to look toward the Negro League. Larry Doby (pictured above with Robinson) was signed by the Cleveland Indians in 1947, and by 1948, he was leading the team to their first championship with another Negro Leaguer, pitching legend Satchel Paige. On his own team, though, Robinson struggled with his relationships with his Black teammates. In 1948, the Dodgers signed catcher Roy Campanella from the Negro Leagues. "Campy," like Robinson, became a Hall of Fame player and a star on the Dodgers. However, as reported by The Philadelphia Inquirer, the two were not close.

Robinson's abrasive style did not jell with Campenella's mellow personality. When another Negro Leaguer, Don Newcombe, joined Brooklyn, Jackie challenged Newcombe to be better, while Campenella went easy on the newcomer. Robinson was also angry because, with Campy's friendly, apolitical personality, he was more appealing to white audiences. This criticism would come up from Robinson again with other Black baseball players. In his book Baseball Has Done It, Robinson criticized Willie Mays and Maury Wills for being silent on racial issues, AL.com reports.

Still, not every politically active African American was a friend of Robinson. When Muhammad Ali refused the Vietnam draft, Robinson criticized him, saying, "Cassius has made millions of dollars off of the American public, and now he's not willing to show his appreciation to a country that's giving him, in my view, a fantastic opportunity," The Atlantic reports.

The running joke about Pittsburgh

42 featured a running joke that teammates who did not want to play with Robinson were traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates, which the film portrayed as a fate worse than death. That makes sense, as according to The Hardball Times, the seasons following World War II had not been good ones for the Pirates, to say the least. The seeds of change were planted in 1950, though, when the team hired a new executive to guide the team to a better future. Maybe you've heard of him.

Despite his success with the Dodgers, Branch Rickey was forced out by the new Dodgers owner, Walter O'Malley, in 1950. Pittsburgh quickly hired Rickey to become the general manager, vice president, and limited partner to the team. Over his tenure, Rickey would draft and develop young prospects to build a championship-contending team. This included the controversial move to trade star outfielder Ralph Kiner in 1953 following a contract dispute.

According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Rickey broke Pittsburgh's color barrier by signing Curtis Roberts. However, his big splash came by drafting Roberto Clemente, a 20-year-old native of Puerto Rico who would become one of the greatest players in MLB history. Poor health ended Rickey's reign in 1955. In 1960, led by players Rickey signed, the Pirates upset the New York Yankees to win the World Series.

Jackie Robinson's time in the Civil Rights Movement

Jackie Robinson's integration of the MLB was the opening shots of the Civil Rights Movement. Postwar America could no longer portray itself as a democratic flag-bearer versus the Soviet Union and the defeated Third Reich and legislate racial segregation within its own borders. Ken Burns' documentary on Jackie Robinson opened with a quote from Martin Luther King Jr. on the baseball player: "He was a sit-in-er before sit-ins, and a freedom rider before freedom ride." History Lives reports something else King said, shortly before his murder, of his predecessor in the Civil Rights Movement: "Jackie Robinson made my success possible. Without him, I would never have been able to do what I did."

Robinson used his platform during and after his playing days to continuously fight for civil rights and the end of segregation throughout the United States. This included letters to multiple presidents and working closely with the NAACP and the rest of the Civil Rights Movement in the South.

At the same time, Robinson's conservative integrationist philosophy also made him plenty of enemies in his own community. He controversially supported Richard Nixon over John F. Kennedy in the 1960 election. The Undefeated detailed his long and public feud with Malcolm X and anyone associated with him, including Congressman Adam Clayton Powell and Elijah Muhammad. Robinson also criticized the Black Panthers and the Black power movement of the late '60s as they, in turn, viewed him as an "Uncle Tom."

Branch Rickey's life and career

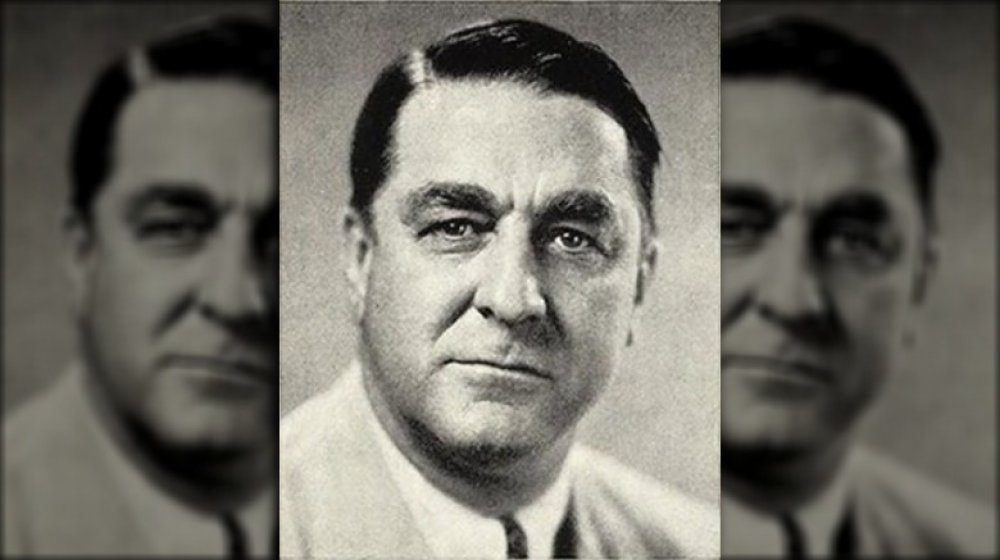

42 is primarily the story of Jackie Robinson, with Branch Rickey playing a secondary role as the white authority figure who supports Robinson. Because of this, Rickey's own life, save for a conversation with Robinson in the trainer's room near the film's end, is kept in the dark.

Wesley Branch Rickey was born in Ohio in 1881. He played both baseball and football at Ohio Wesleyan University. According to Black College Nines, Rickey was declared ineligible to continue to play at university, so he was named the coach for both the baseball and football team. He integrated the team by adding Charles Thomas to play for him. Like Robinson, Thomas was the star of Rickey's team and endured racial taunts, which had a lasting effect on Rickey.

The Baseball Hall of Fame credits Rickey for creating the modern-day baseball farm system while he worked in the front office of the St. Louis Cardinals. Rickey spent more than two decades with the Cardinals, with six of those years as the manager. Rickey's farm system developed two World Series championship teams in St. Louis in the 1930s before he joined Brooklyn.

Still, Rickey was a product of his time. He looked down on Negro League organizations and refused to negotiate with them when signing Robinson, a practice other teams would pick up. At a meeting of Black elites, he said that Black people themselves were the main enemy of Robinson's success, according to The Nation.

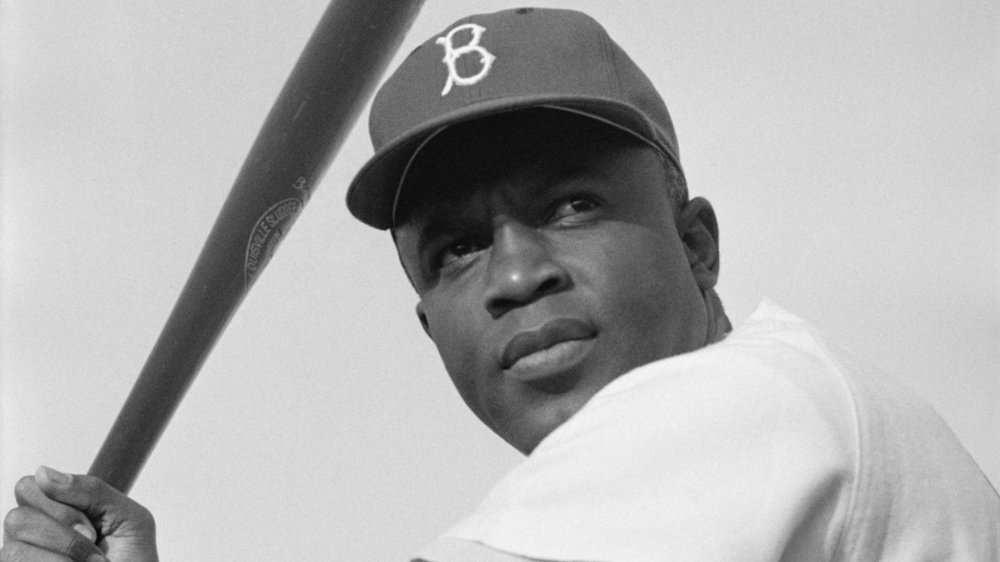

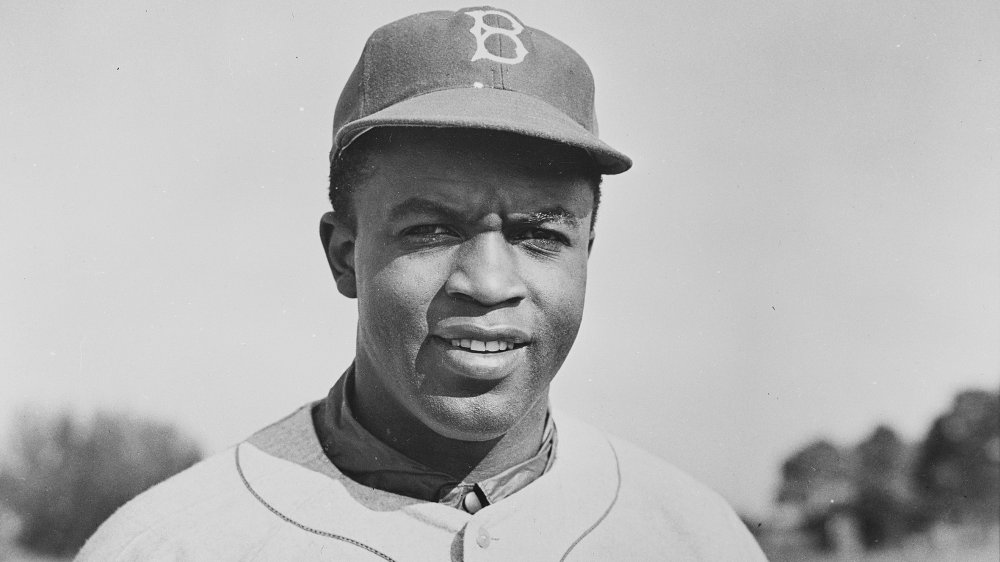

The rest of Jackie Robinson's baseball career

42 only shows Jackie Robinson's rookie season. This is understandable, given that by the end of the season and beginning of 1948, integrating professional baseball was underway, and no amount of fan or player backlash was going to stop this. Still, Robinson would play nine more seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen said of Jackie, "Give me five players like Robinson and a pitcher and I'll beat any nine-man team in baseball." In his first season, Robinson won the inaugural Rookie of the Year award, and two years later, he would have his best season and win the National League MVP award. Robinson's early success came in spite of the that he was already 28 years old when he entered baseball. Robinson's teammate Don Zimmer said this of Robinson's age when he made his debut: "If Jackie Robinson had come to the majors at 20, 21, 22 like most of us did at that time, he'd probably have broken every second base record."

Following the 1956 season, Robinson retired from the game. He became the first African American elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962. In 1972, after years of suffering from diabetes and heart disease, Robinson passed away from a heart attack at age 53. In 1999, he was named to Baseball's All Century Team. Today, Robinson's number 42 is retired throughout baseball, only worn by every team on April 15, the day Robinson made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers.