The Real Reason You Didn't Learn About These Female Scientists

Women and science didn't mix too well in the lab back in the day, but a select few found a way to defy the odds anyway. These women invented and discovered remarkable things that turned into lifesaving breakthroughs that changed our world for the better. And while they may have been lost for a time, they haven't been forgotten. Despite the lifelong limitations, and sometimes hostile attacks they endured, they persevered.

Practically speaking, without the women below, the world may have never had computers, the Environmental Protection Agency, or a man who successfully landed on the moon, among many other life-altering discoveries.

So why are many of these women virtually unknown? While sexism and racism are the obvious reasons, most of these impressive scientists were often upstaged, or coupled with a man's achievements. Luckily, they have begun to receive the widespread recognition they so deserve in the modern age, thanks to spotlights like Google Doodles. It's time to get to know the true geniuses behind the magic of scientific history and grant them the accolades they deserve.

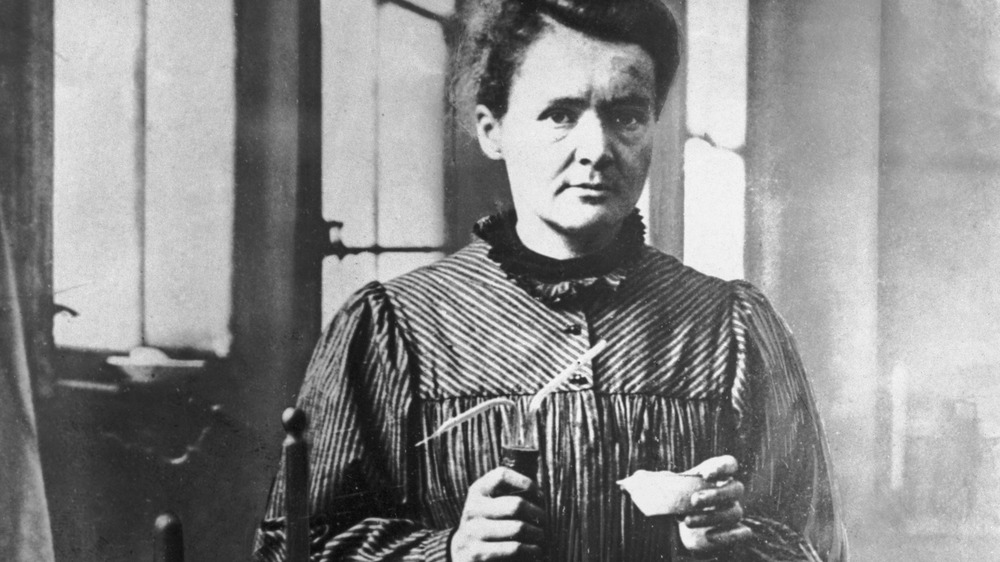

Marie Curie and radioactivity

Marie Sklodowska, who later became Marie Curie by marriage, was a Polish chemist who became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, alongside her husband, for physics in 1903. She later won another solo Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1911.

She met her husband and future working partner, Pierre Curie, while studying at the Sorbonne in Paris. Women weren't allowed to attend university in Poland at the time. Together, Curie and her husband conducted groundbreaking research that led to discoveries in polonium and radium. Marie Curie is responsible for four elements on the Periodical Table: polonium, (Po 84) named after her homeland, francium, (Fr 87) named after her adopted country, radium (Ra 88), and curium (Cm 96), named after the Curies.

Marie Curie's enthusiasm for and promotion of radium as a therapeutic tool for wide-use would later prove to be quite harmful. Unaware of the longstanding health defects of radium exposure, she would keep tubes of it in her pocket. It was only until both a fellow researcher and her personal assistant died of a blood disease did she start to realize its power. On the other hand, radiation kills bacteria in food and has many other positive uses today.

Were the Curies indirectly responsible for the atom bomb due to their findings in radioactivity? Their discoveries did lead to the development of nuclear energy. And while nuclear energy has led to positive societal developments, it has also led to destructive ones — leaving the Curies a tad controversial.

Rachel Carson's Silent Spring

Rachel Carson was a nature writer and marine biologist who became determined to educate the public on the dangers of chemical pesticides. Her bestselling book, Silent Spring, remains both useful and controversial to this day.

Why? It wasn't popular for a woman to speak her mind on serious matters in the mid-20th century, and for Carson it was a struggle to be taken seriously. She was attacked and often dismissed as hysterical for her strong criticisms of DDT and the harmful effects it had on the environment. She has even been dubbed a "mass murderess" for being responsible for the banning of DDT, which acts as a mosquito repellent and can prevent the transmission of malaria.

The attacks had little to do with her intellect or gender, however, and everything to do with big business — mainly various chemical companies and lobby groups who sought to profit off of pesticides. Unfortunately, she wouldn't be the last environmentalist to be attacked by corporate interests, which is at the forefront of the modern battle against the climate crisis.

Carson played the long game, however. Her efforts eventually paid off when in 1972, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a cancellation order for DDT based on its dangers to wildlife and to human health. In fact, Carson's work was what led to the very creation of the EPA in 1970. She is still thought of as the godmother of the modern environmentalist movement.

Katherine Johnson's rocket trajectories

While working for NASA, Katherine Johnson didn't have a fancy computer to help her decipher the precise trajectories that allowed the Apollo 11 mission to land on the moon. She just had some paper, a pencil, and her remarkable brain. That brain literally helped put Neil Armstrong on the Moon in 1969.

Johnson was actually called "a computer," and her specialty was calculating rocket trajectories based on various flight patterns. Her trajectories were also crucial in John Glenn's mission to orbit the Earth. These calculations needed to be hyper accurate, as one tiny fraction of a mistake could completely ruin the mission at hand.

Unfortunately, working at NASA in the Jim Crow era wasn't easy for an African-American woman, and history largely ignored women like Johnson for decades. But Johnson finally gained the recognition she deserved in 2015, when President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, proclaiming, "Katherine G. Johnson refused to be limited by society's expectations of her gender and race while expanding the boundaries of humanity's reach."

In 2016, the biopic Hidden Figures brought her story, along with fellow African-American female NASA mathematicians, to the big screen. Johnson stood out among the group of brilliant women because she attended NASA meetings, where women generally did not belong. She was a leader, unafraid and undaunted by the tremendous adversity she faced.

Ada Lovelace: the enchantress of numbers

Ada Lovelace is known as the founder of scientific computing, and there would be no Apple or Microsoft without her. It took quite a while for the word to get out about her in the modern age, however. Why? Lovelace was born in 1815, at a time when women had few opportunities other than being a wife and mother, or a nun. And even if they did have other interests and were able to practice them, they were rarely taken seriously for their efforts.

As an analyst and metaphysician, Lovelace's works led to many future scientific developments, such as computer-generated music. But in her lifetime, most of her work was veiled behind men like Charles Babbage and Luigi Menabrea.

Babbage was a professor at Cambridge, a fellow scientist, and friend of Lovelace's, who referred to her as the "Enchantress of Numbers." But he may have overshadowed her achievements. Babbage enlisted Lovelace to help him articulate his plans for an engine, for which he could not have done without her unique skills. She also published a translation of an analytical engine by Menabrea, an Italian engineer. Her translation outlined a "sequence of operations for solving certain mathematical problems," which is why some consider her to be the first programmer as well.

Today, Lovelace has finally received credit for envisioning what eventually became the general-purpose computer. But her name is still widely unknown outside of computer science circles.

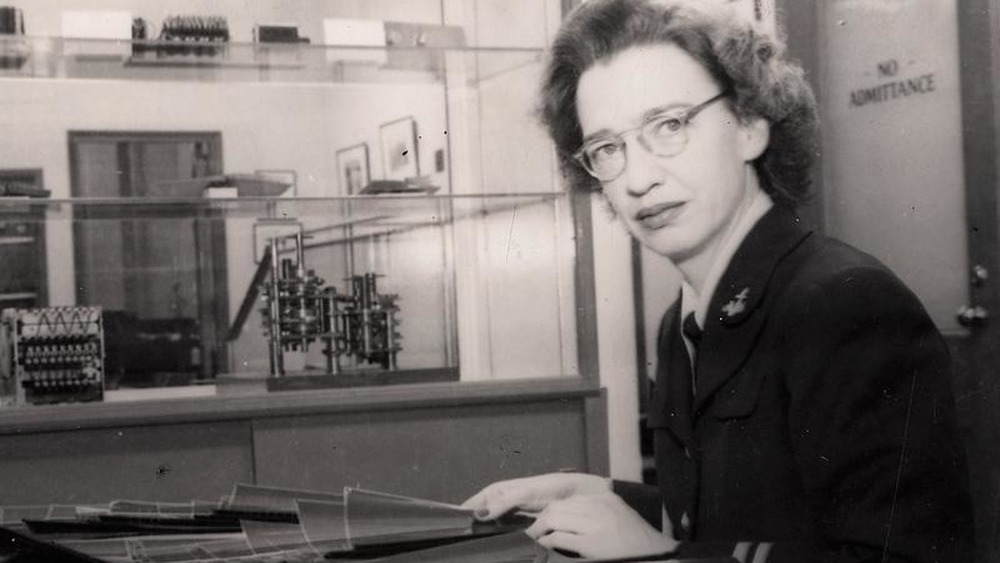

Grace Hopper: naval hero

Grace Hopper was another revolutionary mind in early computer science, who achieved what few women were able to in her day. Hopper believed that computers would someday be more widely used, and she was part of making them more user-friendly. She was a naval officer who joined the United States Naval Reserve during World War II, where she worked for Howard Aiken, the developer of the IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, more commonly known as the Mark I.

Hopper was one of the first computer programmers ever and was responsible for programming the Mark I. She later went on to work on the Mark II and Mark III. Hopper is also credited for "computing rocket trajectories, creating range tables for new anti-aircraft guns, and calibrating minesweepers," according to YaleNews, one of her alma maters.

While working for the private sector, her team created the first compiler for computer languages, which eventually became the Common Business Oriented Language (COBOL) that was utilized around the world. Hopper kept working on computers in post-retirement and was awarded the National Medal of Technology in 1991 — the first female ever to receive the honor. Five years after her death in 1997, a missile destroyer was named the USS Hopper in her honor.

Hopper's name has rarely been mentioned outside of naval and computer academia circles, but it's time to change that.

Barbara McClintock's discovery of jumping genes

Geneticist Barbara McClintock is known today as one of the pioneering figures of modern genetics and is now credited for discovering genetic transposition, which is basically the ability of genes to transform. Cytogenetics, which is the pairing of cytology and genetics, proved that genes were physically positioned on chromosomes.

McClintock got her start dissecting heredity and the inheritance of genetic traits in agricultural products such as corn and peas. Her findings led to the understanding of certain characteristics, such as color mutation, and how these factors linked to the plants' chromosomes. This led to the discovery that genes can "jump" and aren't as structured as once thought but are actually transposable. Before McClintock's discovery, genes were generally considered to be stable entities arranged in an orderly linear pattern. But her findings were not immediately accepted within the scientific community, nor were they even taken seriously. "It didn't bother me," McClintock said about the initial reaction to her work. "I just knew I was right."

Nevertheless, her findings would eventually become appreciated when it came to understanding how certain diseases mutate, as well as finding cures and treatments for diseases such as Lou Gehrig's, schizophrenia, and autoimmune disease.

McClintock won the Nobel Peace Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983, and her name is finally becoming more widely circulated outside of the medical science community.

Ruby Hirose and the polio vaccine

Ruby Hirose was a Japanese-American biochemist and bacteriologist whose work led to the development of polio and hay fever vaccines. She was one of the few women recognized by the American Chemical Society and later contributed to developing more vaccines, such as the fight against infantile paralysis.

Born in 1904, she was part of the Nisei generation, more commonly known as the second generation of Japanese Americans. Growing up in Washington state around a predominantly white population, she experienced both racial and economic discrimination. Both her parents worked in the food manufacturing industry, and Hirose was one of eight children. Despite the odds, she managed to earn a master's in pharmacology in 1928 and then a doctorate in biochemistry in 1932. After graduating, her research focused on developing serums and antitoxins for blood clotting, allergies, and viruses. During a time in American history where Japanese Americans were being held in internment camps, including Hirose's parents, while the polio epidemic raged on, Hirose got to work. Not only was she part of discovering an effective vaccine for polio, but she also made advances in relief for hay fever sufferers, like herself.

Despite the marginalization she experienced due to her race and gender, Hirose made an invaluable contribution to the world with her work on developing vaccines. It's time the word gets out that women like Hirose existed long before they were given "permission" by society, even when her parents were being persecuted in their own country.

Alice Hamilton and workers rights

Alice Hamilton was a physician whose lasting legacy was making the workplace less dangerous. She is known as the First Lady of Industrial Medicine.

After finishing her studies in pathology, she and her sister traveled to Germany to pursue their prospective fields. Hamilton was, however, refused the opportunity to study bacteriology in Berlin, Leipzig, and Munich due to her gender. She finally found a place in Frankfurt where she was warmly welcomed as a research scientist. When returning to the U.S., Hamilton worked as a bacteriologist at Chicago's Memorial Institute for Infectious Diseases, where she examined possible causes of typhoid fever and tuberculosis. This is when she began to see a pattern in the patients' working conditions.

Due to her expertise in public health, she was appointed to the Illinois Commission on Occupational Diseases. Soon after, she also became a special investigator for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, where she discovered white lead substances that were used as pigments in the paint industry. Hamilton was able to make recommendations to improve upon working conditions for factory workers. She also made gains in reforming the damaging effects of manufacturing explosives, carbon monoxide, aniline dyes, radium (thanks Marie Curie), and mercury in the workplace, among other harmful properties.

It was thanks to Hamilton that effective laws and regulations were passed to improve working conditions for poor and marginalized laborers who had suffered for too long.

Rakhmabai Raut and women's rights

Rakhmabai Raut was the first practicing female doctor in India in the 19th century. She was also a human rights activist who called for an end to child marriage, which she herself had personal experience in.

Raut was forced into child marriage at the age of 11. She disputed the marriage in court but was denied justice. Raut wrote letters to the Times of India, addressed to Queen Victoria, who recognized her plea and overturned the court's ruling.

Since the marriage was annulled, Raut moved to London to study medicine, which was unheard of for women in India at the time. She returned to India to practice medicine in Mumbai for over 35 years. She also became an outspoken advocate for marital consent, as well as a proponent for raising the legal age of consent.

Though she is considered a pioneer in medicine and activism for Indian women, she is relatively unknown around the world, and sadly, even in her home country. She was, however, featured in Google Doodles recently, and a wonderful illustrative slideshow was created about her.

Mary Golda Ross: engineer and pilot

Mary Ross was not only a brilliant Native-American female mathematician and engineer, but she was also a pilot. As a member of the Cherokee Nation, Ross was a trailblazer for Native-American women and known as the first Native aerospace engineer.

Ross moved to California in 1941 and became the first female engineer to work for Lockheed. She also worked for NASA and helped write their Planetary Flight Handbook Vol. III, which touched on space travel to Mars and Venus. She is largely remembered within the scientific community for her talents in aerospace design. Ross created design concepts for interplanetary space travel and contributed to designs for the first orbiting satellites for "both defense and civilian purposes." She was also a member of the "top-secret team planning the early years of space exploration," according to American Indian Magazine.

You can catch Ross on a special $1 U.S. coin, as well as a Google Doodle presentation that was featured on the site for her 110th birthday, but she is still unknown to the masses.

Marie Paris Pishmish and the stars

Marie Paris Pishmish was a Turkish-Armenian astronomer who revolutionized astronomy in Mexico. The astrophysics program that she founded in 1955 has remained in place at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. She is considered the mother of Mexican astronomy.

Pishmish was born to an Armenian family in Istanbul in 1911 and attended an American school there. When it came time to graduate, it was expected of women to marry and have children. But Pishmish decided to opt for higher education instead. She perfected many languages, including French, German, and English, and graduated first in her class at Istanbul University. She then obtained her doctorate in mathematics, where she wrote her thesis on the rotation of the Milky Way. From there she moved to the U.S. to study astronomy at Harvard, where she met her future husband, a Mexican mathematics student named Felix Recillas. The couple moved to Mexico City to establish the astronomy field there.

When Pishmish and Recillas arrived in Mexico, they were the only trained astronomers in the entire country. Pishmish dedicated the remainder of her life to educating Mexican students about the stars. There may be 22 stellar clusters that bear her name, but down on Earth, she is still largely an enigma.

Ynes Mexia: botanist and conservationist

Ynes Mexia was a Mexican-American botanist and adventurer who traveled through Mexico, Peru, and Brazil alone in the 1920s and 30s, when it was unheard of for a woman to do so.

Mexia suffered a nervous breakdown after two failed marriages and traveled for 13 years around the Americas following her breakdown. She didn't actually begin her career as a botanist until she was 55 years old. She collected more than 145,000 plant specimens on her travels, along with 500 new species (some of which are named after her).

She was also a staunch conservationist and fought to preserve the redwood forests of Northern California as a member of the Sierra Club.

Mexia battled a triple threat of sexism, racism, and ageism but still managed to carve out a place for herself as an impressive Latina scientist. PBS produced a short film about her.