The Untold Truth Of The Pinkerton National Detective Agency

For over 75 years, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency terrorized workers who were trying to organize in the United States. Although they're often lauded for their diverse hiring practices, more often than not these practices were carried out for the purposes of class warfare.

A Pinkerton agent was responsible for testifying at the sham trial after the bombing of Haymarket Square, but despite the fact that the Illinois governor called the Pinkertons unreliable narrators and pardoned the living Haymarket anarchists, their reputation held strong. And in 1914, the Pinkertons were also part of the Ludlow Massacre, where 66 people died after Pinkertons and the Colorado National Guard set fire to a miners camp.

But the extent of their private police practices and strikebreaking wouldn't be revealed until a federal investigation in the 1930s, at which point the damage had already been done to dozens of labor movements across the United States. This is the untold truth of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

The union of Pinkerton and Rucker

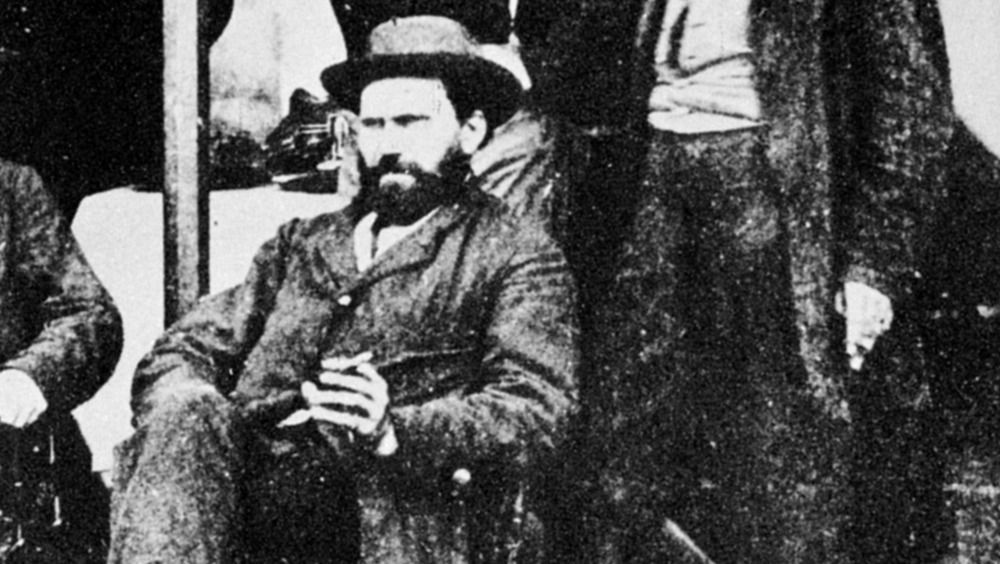

Allan Pinkerton immigrated to the United States of America from Scotland in 1842 and for a time he worked as a barrel-maker in Chicago, Illinois. But one day, in an attempt to save money on barrel hoops, Pinkerton stumbled across the hideout of local counterfeiters. According to Legends of America, it was this "accidental involvement" that led to Pinkerton being appointed deputy sheriff for Kane County.

In 1847, Pinkerton joined the Chicago Police Department and within two years he became Chicago's first police detective. The National Parks Service states that he was even a "special agent for the U.S. Post Office in Chicago" at one point.

The next year, in 1850, along with Edward Rucker, a local attorney, Pinkerton created the North-Western Police Agency. Initially founded as a private police force, per Teen Vogue, it wasn't long before Pinkerton and Rucker dissolved the police agency. But although the North-Western Police Agency only lasted around one year, by that point Pinkerton's brother, Robert, had established himself as a "railroad detective," so the Pinkerton brothers joined forces to create the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

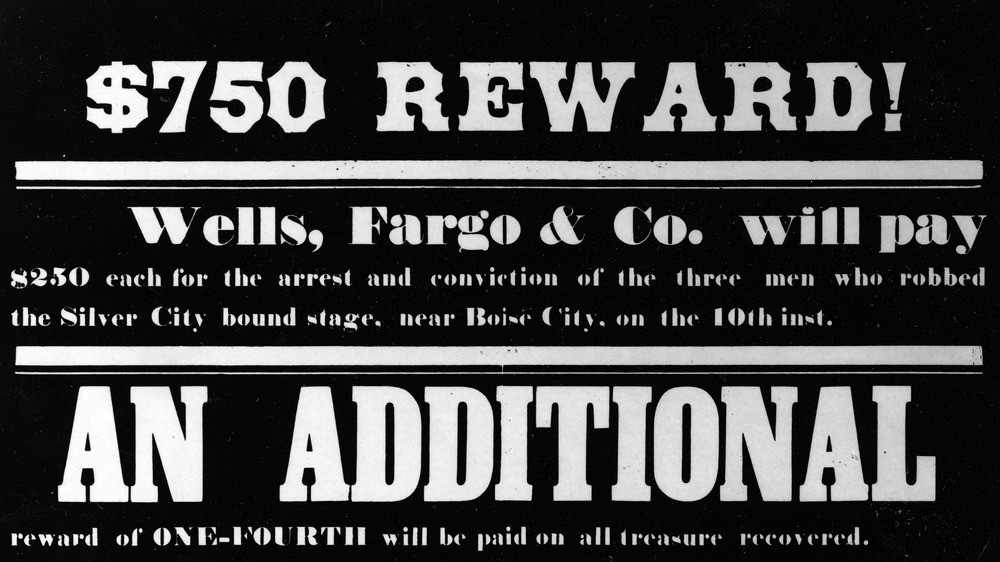

Robert Pinkerton and Wells Fargo

Robert Pinkerton had formed Pinkerton & Co. in 1843. Although he initially worked as a railroad contractor, he soon started specializing as a railroad detective and Wells Fargo soon became his main client. According to The Early Pinkertons by Margaret Pinkerton Fitchett, As the Wells Fargo Express pushed further and further west, the risk of theft and robbery grew greater and greater. Robert Pinkerton realized that he could offer a service to railroads, "an operation designed to secure the safety of goods and parcels in transit and, so far as possible, prevent pilfering by staff or criminals." Although they acted more like "transit police" than actual detectives, Robert Pinkerton's company soon had a number of contracts with Wells Fargo.

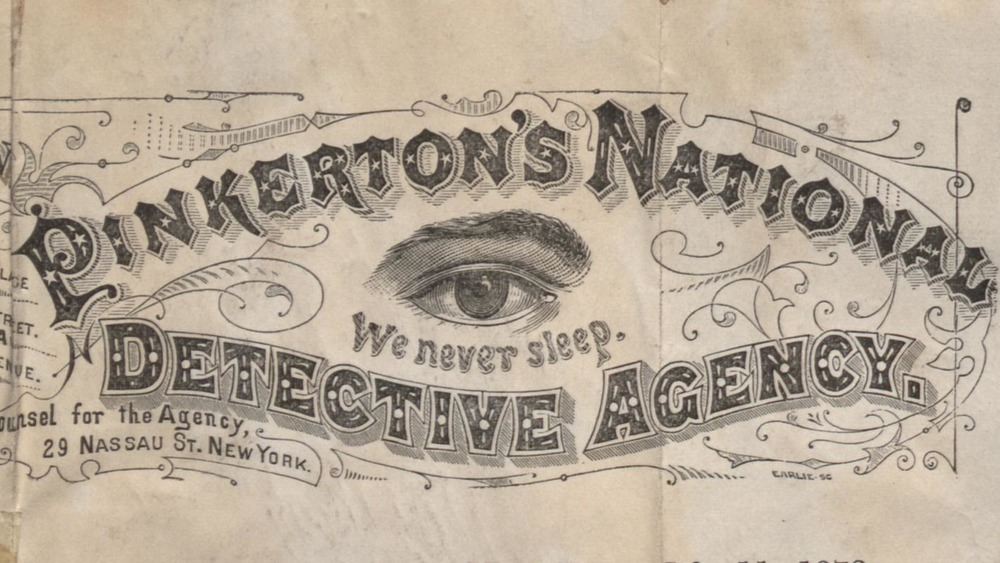

But once Allen dissolved his business and the brothers joined forces, the nature of their business expanded. In addition to providing security guards and private military contractors, they also started to work on catching train robbers and counterfeiters. With an unblinking eye as their symbol and the motto "We Never Sleep," PBS asserts that they played a part in creating the term "private eyes."

After Robert died in 1868, Allan took over the detective agency. But the following year, Allen was impaired by a stroke and as a result their respective sons took on much larger roles in the detective agency.

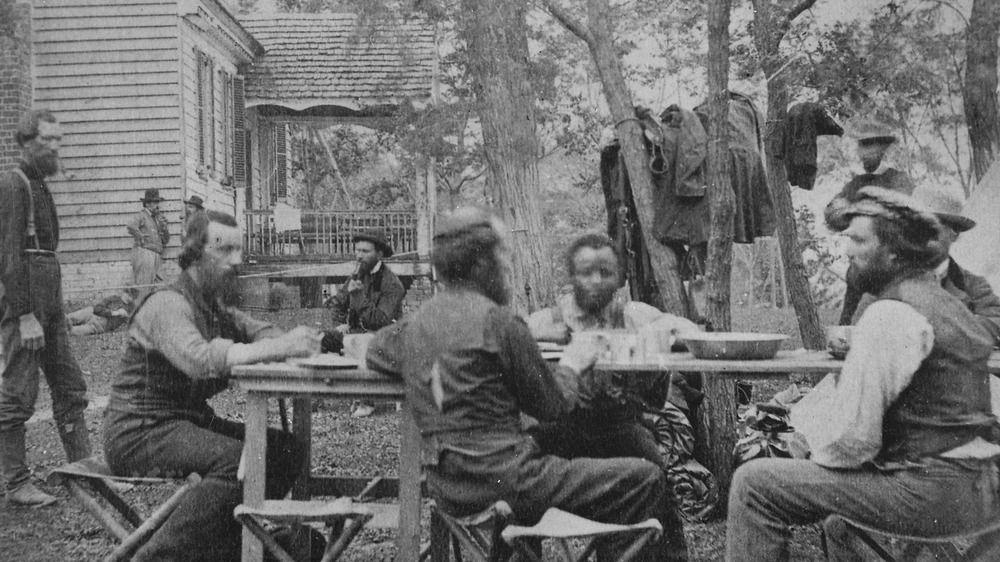

Pinkerton Detectives and the Civil War

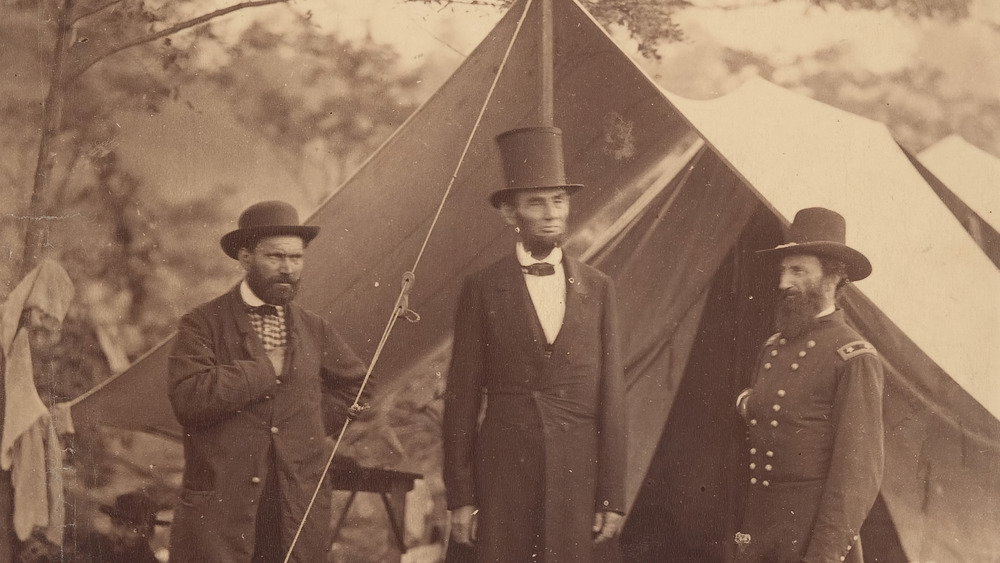

During the Civil War, Allan Pinkerton worked for the Union as the head of their Intelligence Service, although he worked under the name "E.J. Allen." Pinkerton's agents infiltrated the ranks of the Confederacy and Southern sympathizers and reported their military secrets back to the Union. Pinkerton also relied on Black people who had escaped enslavement for information about the Confederacy.

According to the Pinkerton website, one of the men recruited as a Union Intelligence officer was John Scobell, the first Black Union Intelligence officer who had been formerly enslaved in Mississippi. However, in "The Myth of Ex-Slave Turned Civil War Spy John Scobell," Corey Recko claims there's little-to-no proof that Scobell ever existed. Instead, he suggests that Scobell was a fictional character invented by Allan Pinkerton.

Although Pinkerton was known to exaggerate his exploits, he was in fact responsible for foiling an assassination attempt on Lincoln's life right before his first inauguration in 1861. Pinkerton and his agents discovered that "conspirators, in league with members of the Baltimore police force, planned to assassinate Lincoln as he rode in an open carriage." But by arranging for the Harrisburg telegraph lines to be cut, Pinkerton was able to ensure that few heard of Lincoln's sudden departure from Pennsylvania back to Washington, D.C. Pinkerton also reportedly physically restrained two journalists in order to keep them from reporting their plan.

Contracted by the Department of Justice

One year after the Department of Justice was created in 1870, they were allocated $50,000 by Congress in order to create a division within the department meant for "the detection and prosecution of those guilty of violating federal law." However, the DOJ soon realized that the funds weren't enough for them to mount investigations of their own, so they decided to contract out these services to private detectives. There were a few agencies vying for the contract, but of course Pinkerton National Detective Agency was the lucky winner.

Although the contract was a huge gain, according to Pinkerton's Great Detective, the agency was still struggling financially. And in 1871, the agency's main office was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire. Hundreds of criminal records were destroyed, along with "the only copy in existence of the complete records of the Secret Service of the Army of the Potomac."

Pinkerton claimed the loss of the Chicago offices amounted to at least $250,000, and by November 1872, Pinkerton "was forced to take a loan from his employees, and then to mortgage personal property." And with the financial crisis of 1873, Pinkerton lost even more when "the value of his railroad stocks plummeted."

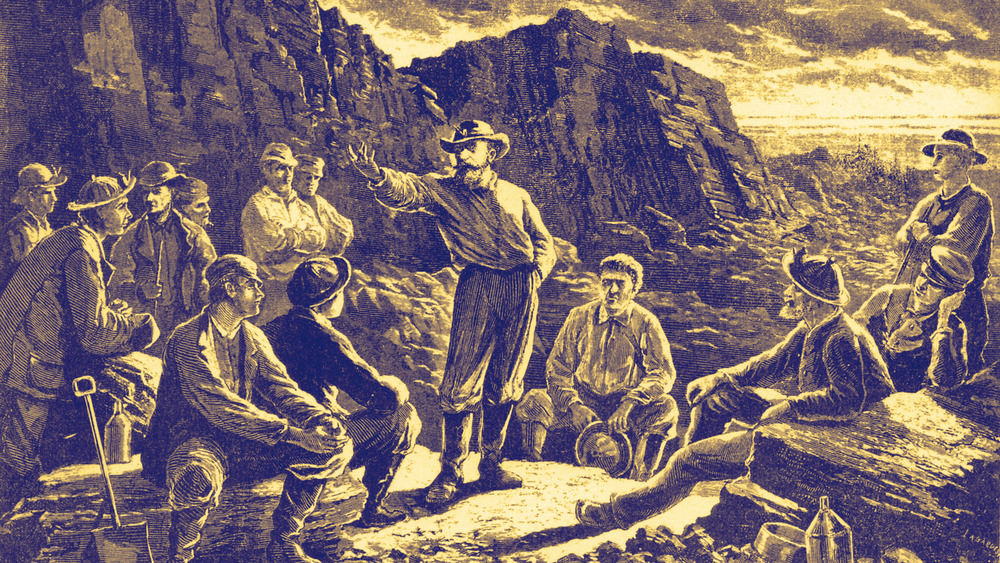

Investigating coal mine labor unions

In 1873, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency started to figure out their niche when they were hired by Franklin B. Gowen, president of Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, to infiltrate the striking Irish immigrants miners. One of their first investigations found the Molly Maguires, a secret society in Ireland that fought for workers' rights, was responsible for violence during the strikes.

According to the Pennsylvania Center for the Book, a Pinkerton detective named James McParland, a native Irishman, claimed to have infiltrated the Molly Maguires. With his help, police arrested 60 miners under the accusation that they were part of the Molly Maguires and with the arrests the strike was defeated. However, despite the strike ending, the men were still forced by the mine owners to stand trial between 1875 to 1877 in order to "uncover alleged crimes committed by the Molly Maguires."

Despite the fact that there was no evidence linking the men to the Molly Maguires and the trials provided no evidence that such a secret society even existed in the United States, 20 men were still sentenced to death by hanging. Public opinion was also heavily swayed against the Molly Maguires, and before their death, the condemned men were excommunicated by Philadelphia Bishop James Frederick Woods. As a result, they were denied a Christian burial. And according to Famous Trials, the trials against the Molly Maguires "fueled discrimination against Irish Americans and suspicion of the trade union movement, both of which lingered for decades."

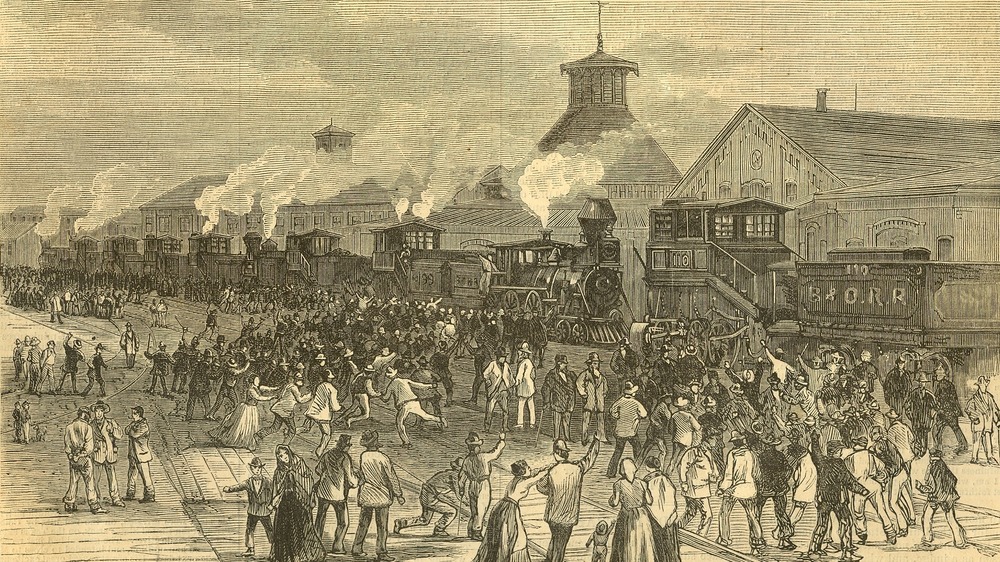

Pinkerton and the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

In 1877, a series of strikes erupted amongst railroad workers across the United States. Railroad workers were already poorly paid, earning roughly $1.75 for a 12-hour day, and then the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad announced a 10 percent wage cut, its second cut in eight months, in July 1877. In response, workers of B&O refused to allow locomotives to leave the station unless the cut was rescinded. While the trains started running on July 20th after the arrival of federal troops, by that point the strike had spread to Chicago and incorporated workers of the Pennsylvania Railroad, who had also recently announced a wage cut.

According to Pinkerton's own recollections of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, "more than three-fourths of the employees of the road, and immeasurably the most deserving, capable, and valuable class of its employees, had received the reduction in an appreciative and manly way."

Meanwhile, railroad companies hired Pinkerton detectives "to patrol their trains and set up security systems" in addition to infiltration and strike-breaking. In his 1878 book Strikers, Communists, and Tramps, Pinkerton claimed that he was protecting workers by breaking strikes and opposing unions, in Army Surveillance in America, 1775-1980, Joan M. Jensen writes that "Pinkertons provided security forces in at least seventy strikes between 1877 and 1892." By the end of the Great Railroad Strike, at least 100 people had been killed and 1,000 people were arrested. Unfortunately, little was changed or reformed as a result.

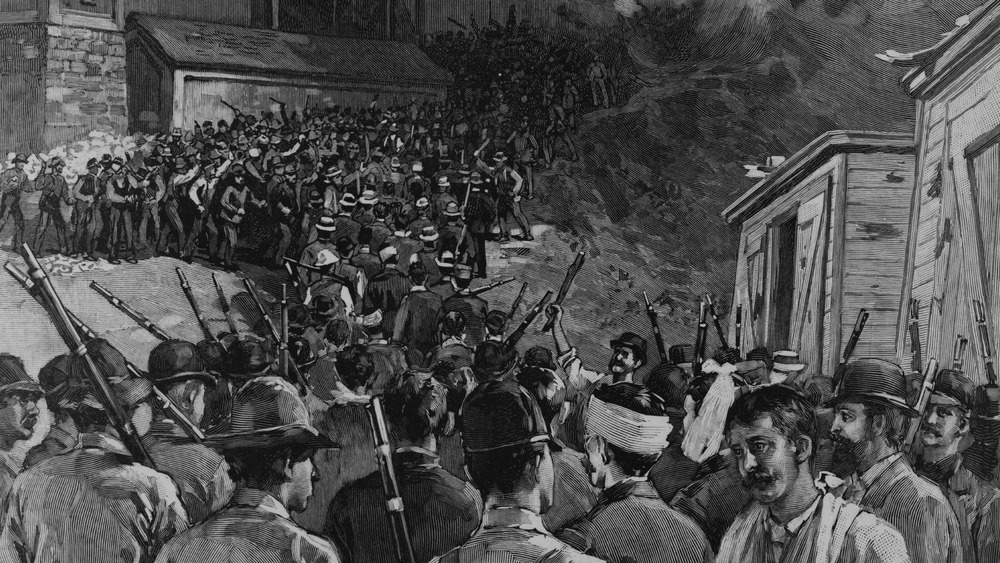

Pinkerton and the Homestead Strike of 1892

Allan Pinkerton died in 1884, but his sons made sure to continue his strikebreaking legacy. And in 1892, the Pinkerton Detectives became notorious after they were recruited to protect scabs at Andrew Carnegie's Homestead mill. According to AFL-CIO, even though Carnegie Steel Co. was making a profit of $4.5 million, roughly $128 million today, they still wanted to cut the wages of over 300 employees, most of whom had already had their pay cut in 1879. Andrew Carnegie and Henry Frick, the chairman of Carnegie Steel Co., wanted desperately to break the Homestead workers' union, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, whom they believed were keeping them from lowering the costs of production.

In an attempt to break the strike, Frick hired the Pinkerton Detectives and tried to sneak 300 agents in on July 6th, 1892. But news spread and soon thousands of workers and their families had rushed out to keep the Pinkerton detectives out of the labor dispute. Although the Pinkerton detectives were outnumbered, gunfire from both sides resulted in the loss of at least 15 lives, 12 workers and three Pinkerton agents.

After the bloody encounter, Frick demanded that the National Guard come to help regain control and over 8,000 soldiers soon arrived. By mid-August, the mill was running again with scabs, and Frick announced that the steel mill will no longer have "any further dealing with the Amalgamated Association as an organization." The union collapsed by November.

The Anti-Pinkerton Act of 1893

The bloodshed didn't go unnoticed by Congress and as a result of the Homestead massacre, 26 states passed laws that banned "bringing in outside guards during labor disputes." And the following year, Congress passed the Anti-Pinkerton Act, which was deliberately meant to keep the federal government from employing the Pinkerton agency, or any "similar organization," to be used in labor disputes.

But the Pinkerton Agency wasn't disparaged, and during the late 1890s, they opened up branches offices in various states "to avoid those state laws that prohibited bringing forces from out of state."

According to Inventing the Pinkertons, in 1977, the Fifth Court of Appeals determined that "the purpose of the Act and the legislative history reveal that an organization was 'similar' to the Pinkerton Detective Agency only if it offered for hire mercenary, quasi-military forces as strike-breakers and armed guards." However, since the court only defined "quasi-military forces," the law now "has little practical effect in the employment of contemporary security service companies or military support contractors."

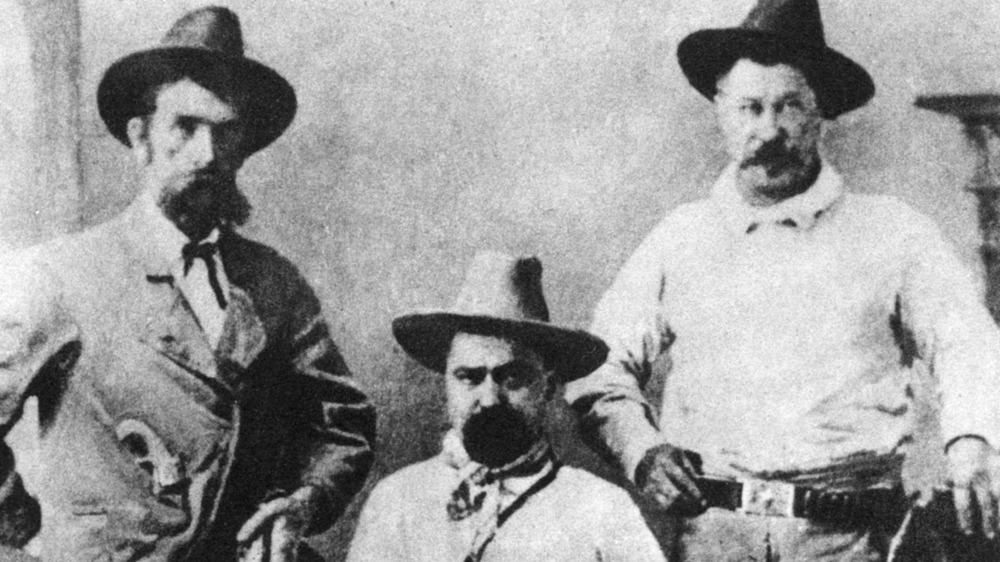

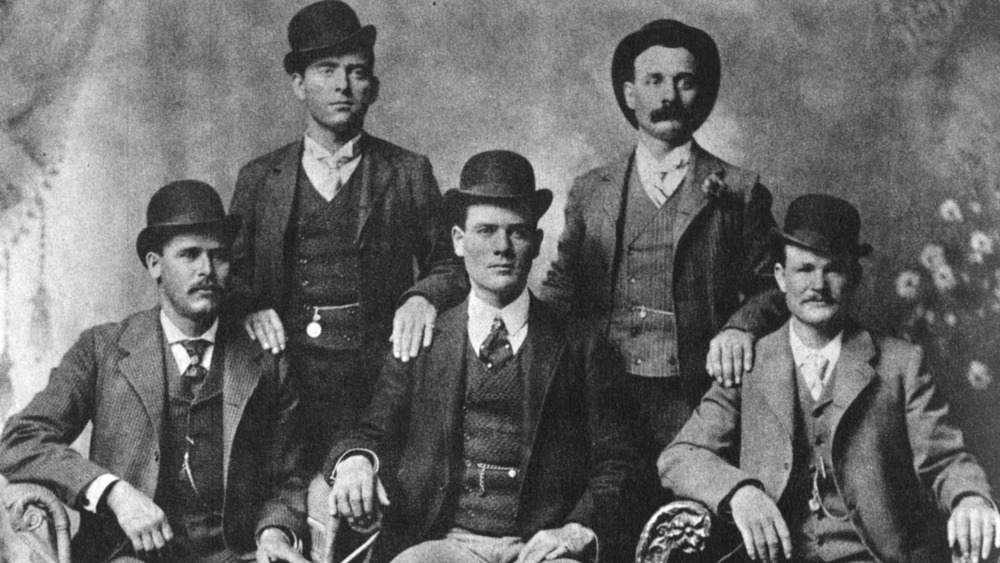

Tracking western outlaws

When Pinkerton agents weren't busy strikebreaking and union busting, they were pursuing famous Wild West outlaws like the Reno Gang, Jesse James, and the Wild Bunch. However, they weren't always successful and sometimes innocent people fell victim to their zeal.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, after the Civil War, the Pinkerton agency worked on a number of high-profile train and bank robberies and recovered hundreds of thousands of dollars. The Reno Gang were some of the first train robbers in the United States and in the late 1860s Allan Pinkerton chased down Frank Reno himself.

In 1875, Pinkerton decided to go after Jesse James and his gang. But after tracking them to James' mother's farm in Missouri, the resulting standoff ended in tragedy. A lantern was thrown into the house, resulting in an explosion that blew off the arm of Zerelda Samuel, James' mother, and fatally wounded 8-year-old Archie Samuel, his half-brother.

Although the public had previously supported the work of the Pinkerton detectives, "the death of Archie Samuel was a public relations nightmare." And as Pinkerton detectives continued to incite riots and help management during labor disputes, their reputation continued to sink. By the end of the 19th century, "the name 'Pinkerton' soon became a dirty word among the working class."

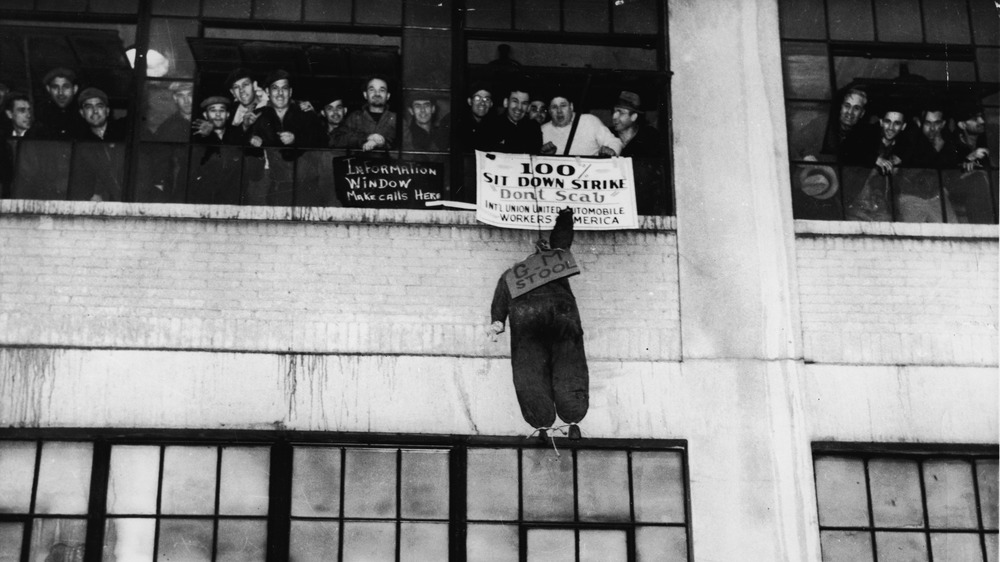

The La Follette Civil Liberties Committee

In 1936, the strikebreaking activities of Pinkerton Detective Agency were finally investigated by the La Follette Committee, also known as the Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee Investigating Violations of Free Speech and the Rights of Labor. The investigations lasted until 1941 and over the course of four years "the most provocative and brutal forms of anti-union activities" were exposed.

According to "The Forgotten Threat: Private Policing and the State," "not only had little changed since Homestead, [but] the tactics of private police had become more violent." The committee also revealed that across the country, almost every single employer who had a labor dispute resorted to private police assistance. And companies like General Motors "paid to the Pinkerton agency alone almost one-half million dollars to spy on its workers and disrupt organizational activity." Industrial espionage was found to be rampant and Pinkerton Detective Agency wasn't the only organization to come under scrutiny. The La Follette Committee also found that the Associated Farmers of California were preventing worker organization to such an extent that the committee described it as "local fascism."

Since the La Follette committee cast such an unfavorable light on private police, in 1937 the Pinkerton Agency ceased all their labor-related police work. However, there were no regulatory changes as a result of the committee's investigations.

Spies across the country

One of the most striking revelations of the La Follette Committee was the extent to which labor spies were scattered across the country. According to the Report of the Committee on Education and Labor, Pinkerton Detective Agency alone employed at least 1,228 spies. Overall, the committee acknowledged the existence of at least 3,871 labor spies from 1933 to 1936. However, the report notes that the real number is likely far greater, since at least 700 detective agencies didn't offer any information on their number of spies.

These professional spies also amassed networks of informants called "hooked men" or "hookers." According to "Industrial Terrorism and the Unmaking of New Deal Labor Law," this made it especially difficult to determine exactly how many spies there were, since "the number were clearly enormous. Indeed, GM employed so many spies from so many sources that it was reduced to hiring spies to spy on its spies."

Another disturbing revelation was the fact that "Little Steel companies used their stockpiles to arm public police forces that allied with them." Apparently, weapons were even presented as gifts in some places in order to build up relations with the public police.

Detective work dissipates

After the La Follette committee and the expansion of the FBI, the Pinkerton Detective Agency wasn't left with as much of the same work as it had initially had. As a result, they started focusing more on protection services, risk management, and active shooter response.

Interestingly, most of Pinkerton's own history is absent from the history page on the Pinkerton website. The first half of the 20th century mentions only how Allan Pinkerton II inherited the agency in 1907 and that Robert Pinkerton II took the helm in 1930.

According to Funding Universe, during World War II, Pinkerton agents were "hired to guard war supply plants," from which they made at least $1.7 million. However, as the years passed, their work as private police shifted more into the role of security guards, such as in 1962, when Pinkerton agents were hired to escort the Mona Lisa as it sailed across the Atlantic. Pinkerton agents were also hired to guard Marilyn Monroe's coffin during her funeral service.

Pinkerton today

In 1999, the Swedish security company Securitas AB purchased Pinkerton for $384 million. According to the Pinkerton website, over the next few decades their work moved into comprehensive risk management and they relocated their headquarters to Ann Arbor, Michigan.

But try as they might, Pinkerton still can't seem to shake its negative image, although they haven't stopped trying. According to Screen Rant, when the Red Dead Redemption games came out, the real-life Pinkerton agency was irritated at the fact that they were being portrayed as the bad guys in the game.

But Red Dead Redemption doesn't even comment on Pinkerton's history as labor spies and strike-breakers, focusing instead on the fact that Pinkerton agents also worked as "bounty hunters-for-hire that would accept contracts from private businesses or even the U.S. government." Pinkerton went on to sue Take-Two Interactive and Rockstar Games, but The Verge reports that in 2019, the suit was quietly dropped.