The True Story Behind The Bride Of Frankenstein

In 1923, Universal Studios became Hollywood's reigning house of horror with The Hunchback of Notre Dame, starring makeup effects legend Lon Chaney. The studio followed the success of Chaney's take on Victor Hugo's novel with another macabre masterpiece starring the man of a thousand faces. The Phantom of the Opera, released in 1925, had audiences fainting in the aisles thanks to Chaney's performance as Erik, the disfigured madman of the Paris Opera. With Chaney's talents and the vision of production head Carl Laemmle, Jr., Universal was on its way to a 33-year horror dynasty.

Universal horror entered its classic period with 1931's Dracula. Directed by Tod Browning and starring Bela Lugosi, the film owes much of its look to cinematographer Karl Freund. An Austrian émigré, Freund was a veteran of the German film industry, who had shot Fritz Lang's groundbreaking Metropolis. Freund brought with him an expressionistic sensibility that marked an evolution in American horror cinema.

Universal would release yet another monster on filmgoers in 1931. Frankenstein, directed by James Whale, was an unparalleled achievement of brilliant direction, superb performances, and technical innovation. Although Dracula held a slight edge at the box office, Whale's Frankenstein was the shining jewel in Universal's horror crown. Obviously, Frankenstein would be a hard act to follow. Yet, Whale would do the impossible when he created a sequel that would be regarded as the greatest of all the Universal monster movies. This is the true story of The Bride of Frankenstein.

The success of Frankenstein assured a sequel

As detailed in Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic, by Mark A. Viera, with Dracula, Universal's head of production Carl Laemmle, Jr., had accomplished what the other studios had failed to do — establish a profitable formula for cinematic horror. Yet, despite Dracula's sizable box office, the film had failed to bring the cash-strapped studio out of the red. Universal's next project would be an adaptation of Frankenstein. Like Dracula, Frankenstein had proven successful on the stage. With Bela Lugosi attached, Frankenstein was money in the bank.

However, bringing Frankenstein to the screen was no easy task. Test footage of Lugosi as the monster was disastrous. The temperamental star insisted on doing his own makeup with laughable results. Lugosi also objected to the monster's mute characterization. Feeling the role was beneath him, the actor left the project. Still, Laemmle was otherwise impressed. The film could work without Lugosi

Laemmle hired James Whale, a 42-year-old British former stage director with a knack for dialogue, to helm the picture. With the addition of an unknown character actor named Boris Karloff as the monster, Whale alumnus Colin Clive as Dr. Henry Frankenstein, and makeup artist Jack Pierce, Laemmle assembled a winning team for Frankenstein.

Released Nov. 21, 1931, Frankenstein was a hit. Hailed by The New York Times as one of the ten best films of 1931, Frankenstein was also one of 1932's top grossing movies. Plans for a sequel to be titled The Return of Frankenstein went into effect immediately.

James Whale, father of the bride

Following his success with Frankenstein, James Whale made several more pictures for Universal, including 1932's The Old Dark House, a gothic horror/comedy that reteamed the filmmaker with actor Boris Karloff, and The Invisible Man, an adaptation of H.G. Wells' science fiction classic.

Having established himself as an imaginative and profitable filmmaker, Whale had little interest in revisiting Frankenstein. According to author Mark A. Viera, Whale seemed indifferent to a sequel. Fearing a redux would dishonor or diminish the original film, Whale stated, "I squeezed the idea dry with the original picture. . . and I never want to work on it again."

Frankenstein had been, as described by Bill Condon, director of Gods and Monsters, "the Star Wars of its day." Obviously, Universal wasn't going to entrust the sequel to an untried director. At last, Carl Laemmle, Jr., was able to entice Whale back for the sequel. This time, Whale would be given unprecedented freedom and full access to Universal's resources to make a film that represented his true vision.

Still Whale felt the film was doomed. As detailed by Susan Tyler Hitchcock, author of Frankenstein: A Cultural History, David Lewis, Whale's partner and housemate, had special insight into the filmmaker's approach to the sequel. "He knew it was never going to be Frankenstein," Lewis told film historian Paul M. Jensen. "He knew it was never going to be a picture to be proud of. So he tried to do all sorts of things that would make it memorable."

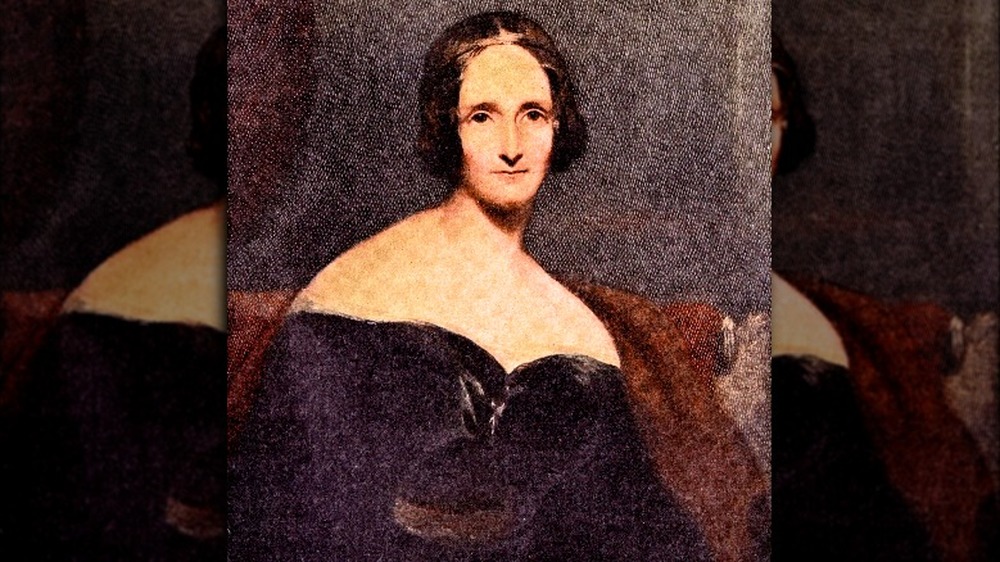

Mary Shelley's inspiration

According to a 1998 retrospective published in American Cinematographer, Robert Florey, the French director who had shot Bela Lugosi's ill-fated Frankenstein test footage, submitted a treatment for a sequel as early as 1931. The story outline, titled The New Adventures of Frankenstein, was soundly rejected by Carl Laemmle, Jr., in February 1932.

At least nine scripts in various states of revision were written for the film to be titled The Return of Frankenstein. For inspiration, James Whale overlooked the various stage versions of Frankenstein and went to Mary Shelley's original text. Reworking an unsatisfactory script by John L. Balderston, the playwright best known for his hit dramatic adaptation of Dracula, Whale partnered first with writer R.C. Sheriff and, later, William Hurlbut to craft a screenplay that would blend humor, thrills, and subversive subtext into the story. Whale's sequel would focus on a major plot point from the novel that had not been explored in the previous film — the monster's desire for a mate. Fascinated by the idea of a female monster, Whale had found his thematic hook.

In Shelley's novel, the monster coerces Victor Frankenstein into creating a female companion as "deformed and horrible" as he to stem his loneliness. Frankenstein constructs the creature's mate but, fearing he is fostering a race of monsters, destroys it before imbuing it with life. However, Whale's protagonist, Henry Frankenstein, would bring the monster's bride to life with horrifying consequences. Whale would drop the title The Return of Frankenstein, instead naming the film Bride of Frankenstein.

The Bride of Frankenstein's new villain

In the 1999 documentary, She's Alive! Creating the Bride of Frankenstein, legendary horror author Clive Barker explains his view of how Bride of Frankenstein provided James Whale with a playground for his inexhaustible creativity. "When you get into Bride of Frankenstein, you're making it all up," Barker says. "There are no rules. The only rules are the rules of the imagination — and Whale had an extraordinary imagination."

Among the imaginative additions Whale brought to the mythos of the manmade monster was an all new villain. In the context of the previous film, neither Henry Frankenstein nor his creature could function as an antagonist in the sequel's plot. A sinister, outside force would be required to provide the impetus for Frankenstein to create the monster's mate. Enter Dr. Septimus Pretorius.

In the film, Pretorious, portrayed with maniacal glee by British character actor Ernest Thesiger, is the former mentor of Henry Frankenstein. Fired from his position as a professor of natural philosophy at the University of Ingolstadt for dabbling in weird science, Pretorious is the man responsible for setting Frankenstein on his quest to find the secret of life. Unable to duplicate Frankenstein's discoveries, Pretorious has instead perfected a way of "growing" miniature humans. Proposing a "new world of gods and monsters," the mad doctor befriends Frankenstein's monster and uses him to force Henry to construct a mate for the creature. With a body constructed by Frankenstein, the Bride will have an artificially grown brain provided through Pretorious' unholy machinations.

New faces and old: the cast of The Bride of Frankenstein

James Whale populated his sequel with an ensemble of new and familiar faces. Frequent Whale collaborator Colin Clive would return as Dr. Henry Frankenstein. No longer an ambitious scientist, Frankenstein as portrayed by Clive is a man broken by the horrors of the prior film.

Mae Clarke, who had portrayed Henry Frankenstein's fiancee Elizabeth in Frankenstein, however, was unavailable for the sequel. According to Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic, Clarke had left Universal Studios and suffered a series of nervous breakdowns that necessitated a retreat from acting. Clarke was replaced with 17-year-old ingenue Valerie Hobson.

The film's star, Boris Karloff, returned as the monster. No longer relegated to grunts and growls, Karloff's pathos-filled performance would set the standard for all future portrayals of the character.

Whale cast his theatrical mentor, Ernest Thesiger, in the role of the evil Dr. Septimus Pretorious. Originally written for The Invisible Man's Claude Rains, the role was a perfect fit for the eccentric 56-year-old stage veteran.

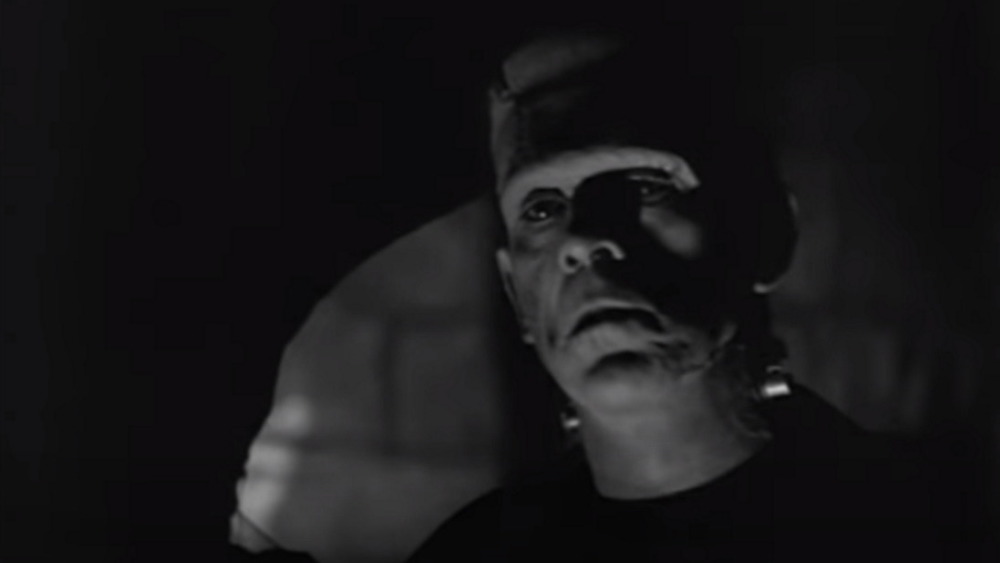

Boris Karloff's evolving monster

In the four years since the release of the original film, Boris Karloff had made a reputation as cinema's favorite bogeyman in such films as The Old Dark House and The Mummy. Now approaching 50, the actor was finally enjoying the fruits of his labor. Consequently, Karloff had gained a few pounds since Frankenstein. No longer a rail-thin, walking corpse, the monster of Bride of Frankenstein is all the more imposing for Karloff's added bulk.

The monster's iconic appearance created by makeup artist Jack Pierce also underwent some subtle changes. The look of the monster's characteristic flattened head and heavy brow, created in a time-consuming process of layering cotton and collodion in the first film, was accomplished with a reusable rubber appliance in Bride. As documented in David J. Skal's 1999 documentary film, She's Alive: Creating The Bride of Frankenstein, the monster, having survived the conflagration that marks the first film's conclusion also bears burns on his face and hand, and his hair has been singed to better reveal the metal clamps holding his skull together.

Yet, the greatest change in the monster is not merely cosmetic. Although the monster wouldn't be the eloquent speaker of Mary Shelley's novel, he would now have a limited vocabulary of 44 words. Nevertheless, Karloff thought giving the creature the power of speech was a mistake. "My father really objected to the monster being given speech," daughter Sarah Karloff told Skal. ". . . I think he was wrong — cinema history has proven him wrong."

Elsa Lanchester: The woman beneath the bandages

Born in Lewisham, London, in 1902, Elsa Lanchester studied under famed dancer Isadora Duncan as a child. She began her career as a cabaret performer before establishing herself as a dramatic actress. Having appeared on stage and in several British films, she emigrated to Hollywood with her husband, actor Charles Laughton, in the 1930s.

Although she appears for just minutes at the opening, as Frankenstein author Mary Shelley and as the monster's mate at the film's climax, Lanchester was key to Bride of Frankenstein's success. According to film historian Paul Jensen, Lanchester's dual roles were essential to James Whale's vision. "Elsa Lanchester told me. . . that Whale insisted that she be allowed to play Mary Shelley and also the Bride," Jensen said in the documentary She's Alive! "It was either that or he wouldn't make the film."

As documented in her autobiography, Elsa Lanchester, Herself, one of the most uncomfortable aspects of making Bride was working with the notoriously irascible makeup artist Jack Pierce. "He had his own sanctum sanctorum, and as you entered . . . he said good morning first," Lanchester wrote. "If I spoke first, he glared and slightly showed his upper teeth. He would be dressed in a full hospital doctor's operating outfit. At five in the morning, this made me dislike him intensely. Then, for three or four hours, the Lord would do his creative work, with never a word spoken . . . But, Jack Pierce fancied himself The Maker of Monsters — meting out wrath and intolerance by the bucketful."

The religious subtext of The Bride of Frankenstein

Much like the monster himself, The Bride of Frankenstein is much more than just the sum of its parts. James Whale, working within the confines of a genre that's often dismissed or outright maligned, conceived in Bride a story rich in subtext and allegory. Through subtle (and at times shockingly overt) use of imagery and dialogue, Whale's film serves as a criticism of organized religion and a parallel of the story of Christ.

The Bride of Frankenstein is replete with Christian imagery. Crosses abound in the mise en scene in both literal form and in subtextual visual cues, such as the monster's capture and torture by angry villagers. Throughout the film, Whale paints the monster as both an inversion to and parallel of Christ. "The monster is manmade, not God-made," film expert Scott MacQueen explains in She's Alive! ". . .Yet, he goes through a Christ-like orbit of misunderstanding and ultimate betrayal."

Amazingly, Whale was able to get much of this sensitive religious subtext past studio censors. However, one scripted sequence in which the monster mistakes a life-size depiction of Christ on the cross in a cemetery for a suffering being like himself was deemed too blasphemous to film. The scene was replaced with the monster angrily toppling a statue of a bishop. An overt attack on institutionalized religion, the alternate sequence somehow made the final cut.

The Bride of Frankenstein as a gay film

Although it was likely not apparent to any but the savviest of moviegoers in 1935, The Bride of Frankenstein is among the most overtly gay-themed films of Hollywood's golden age. In recent decades, the link to James Whale's sexuality and the movie's subtext has made a homosexual interpretation of Bride of Frankenstein one of the chief theoretical approaches to the film.

According to David J. Skal, author of The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, the gay subtext Whale explores in Bride is an evolution of ideas in Mary Shelley's original novel. "Frankenstein is a visionary novel dramatizing, among many other things, a feminist writer's anxiety over scientific man's desire to abandon womankind and find a new method of procreation that does not involve the female principle," Skal explains. "... The impulse is thus autoerotic ... and/or homoerotic — life created with the help of male assistants."

Dr. Septimus Pretorious functions as an expression of heterosexual fears about gay men as he attempts to lure Henry Frankenstein away from his marriage bed to embark on a strange new life.

More broadly, Whale, who lived as an openly gay man in the intolerant 1930s, characterized the monster as a sympathetic and sensitive outsider. Frequently clashing with "angry villagers," the monster and his search for acceptance and love no doubt mirrored Whale's own struggles in finding his place in what at the time was a largely hostile society.

The Bride versus the censors

Although James Whale was able to get most of his subversive ideas in the film in one form or another, Bride of Frankenstein still faced an uphill battle with the Motion Picture Production Code. Also known as the Hays Code (named for Will Hays, chairman of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America and Hollywood's appointed moral gatekeeper), the code functioned as strict guidelines for what could be shown in a publicly exhibited motion picture.

Ultimately, the film underwent 15 minutes of cuts, dropping its original 90 minute running time to 75 minutes. The film's prologue, which features the Shelleys and Lord Byron discussing the ironic implications of demure Mary Shelley conceiving the horror of Frankenstein, was trimmed to eliminate all closeups of Elsa Lanchester's plunging neckline. Other cuts were made to soften scenes of violence and eliminate potentially offensive allusions to religion.

According to The Monster Show, the film faced even more cuts after its national release when it ran afoul of many local and state censorship boards. Internationally, the film was banned outright in Trinidad, Palestine, and Hungary.

The Bride is horror's reigning female icon

From the Phantom of the Opera to the Creature of the Black Lagoon, Universal's original cycle of horror films presents a pantheon of classic monsters. Defining horror for generations, the Universal monsters are as iconic as Santa Claus, Superman, and Mickey Mouse. Among their number is only one female creature — the Bride of Frankenstein.

In the history of horror film, no female character is as recognized or as revered. Much like her male counterpart, the Bride's popularity is rooted in a unique performance coupled with a revolutionary makeup design by Jack Pierce. Elsa Lanchester's unearthly vocalizations and electrified hairdo are as synonymous with horror's golden age as Boris Karloff's flattened skull and lumbering gait. Yet, in a testament to the character's appeal, she appears in just one film for a mere three minutes.

In David J. Skal's She Alive!, film historian Bob Madison explained the Bride's lasting popularity. "The makeup for the Bride of Frankenstein is an absolute masterpiece," Madison stated. "It's the only iconic female monster to ever come out of the movies. If you're to think of a classic female monster, the Bride of Frankenstein comes immediately to mind."

The Bride of Frankenstein's growing reputation

In the 86 years since its original release, The Bride of Frankenstein has come to be regarded as the pinnacle of Universal's monster films. Despite James Whale's ambivalence about his work in the horror genre, the film is his masterpiece. A funny, touching, and above all, entertaining film, Bride of Frankenstein is one of a handful of sequels that exceeds its predecessor.

"The various story elements, the intellectual elements, the artistic and acting elements that came to bear in this film really kind of crystalized all the things that had been building in (the horror genre) at that studio at that time," film scholar Scott MacQueen told David J. Skal. Proclaiming the film "the crowning jewel in Universal's initial series of horror films," cinema historian Bob Madison places The Bride of Frankenstein in the company of the greatest movies of all time. "The Bride of Frankenstein is quite simply the most complex and most brilliantly achieved and conceived horror film ever made," Madison said.