Here's What The Final Dying Wishes Were For These American Presidents

You're about to die. What would be your last wish? Would you give all your fortune to random people found in the phone book as the Portuguese aristocrat Luis Carlos de Noronha Cabral de Camara did? Or would you request, as a cancer-stricken Aldous Huxley did in 1963, a heavy dose of LSD to put you out of your misery? Or maybe you want your ashes to be smoked like Tupac Shakur? This last request was fulfilled some 15 years after his death in 2011.

All people desire something in their last days, and the presidents of the United States are no exception. In doing so, American presidents, for all their power, show a common humanity through their dying wishes. From the subtle to the surprising to the ironic, presidents had their own unique wishes — though none wanted to be smoked or go out on an acid trip. Here are 12 examples to reflect upon while considering your own mortality.

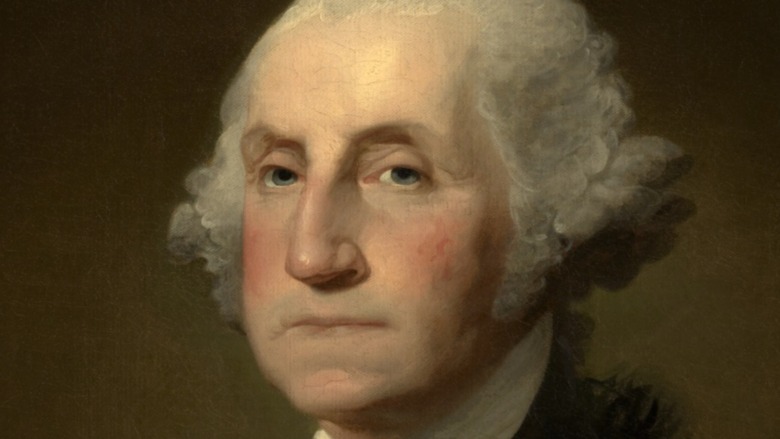

George Washington wanted to make sure he was really dead before he was buried

Called the "Father of His Country," George Washington is one of the most important figures in American history. Not only did Washington lead American forces to victory over the British during the Revolutionary War, but he also established the precedents for the Chief Executive of the United States. What most people don't know is that Washington had a quite reasonable phobia of being buried alive.

As reported by the New England Historical Society, Washington and others of the era suffered from taphophobia, which is fear of a premature burial. This phobia stemmed from literature and myth of the time, which said that many people were buried alive. The thought of trying to claw one's way out of a coffin is as frightening now as it was then. Therefore, upon his deathbed on December 14, 1799, Washington instructed his personal secretary, Tobias Lear, to "Have me decently buried; and do not let my body be put into the vault in less than three days after I am dead." This request was obeyed, and according to Mount Vernon, Washington lay in state for three days before his final interment at Mount Vernon.

Washington's other wish was to free the enslaved people he and his wife Martha owned. As described by the Miller Center, Washington freed his personal slave William and granted him an annual stipend. The larger number of enslaved people owned by Martha were freed after her death in 1802.

John Adams may have wanted to outlive Thomas Jefferson

John Adams was one of the leading figures of the American Revolution and served as the first vice president of the United States under George Washington. In 1796, he ran for and very narrowly won the presidency against Thomas Jefferson. As told by the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, the two Founding Fathers had a close friendship, although they had different political views. In 1800, the two ran against each other for the presidency again in a very dirty race. This time, Jefferson won.

The friendship was broken until 1811, when they reconciled in a long series of letters. This correspondence continued until, according to the Miller Center, Adams died at age 91 at 6:00 p.m. on July 4, 1826. His last words, uttered around noon, were, "Thomas Jefferson survives." Whether this meant that Adams regretted not outliving his rival Jefferson or if he wanted his old friend to outlast him is unknown. It is clear, however, that Adams certainly had Jefferson on his mind. What Adams did not know is that Jefferson died at 12:50 p.m. that same day.

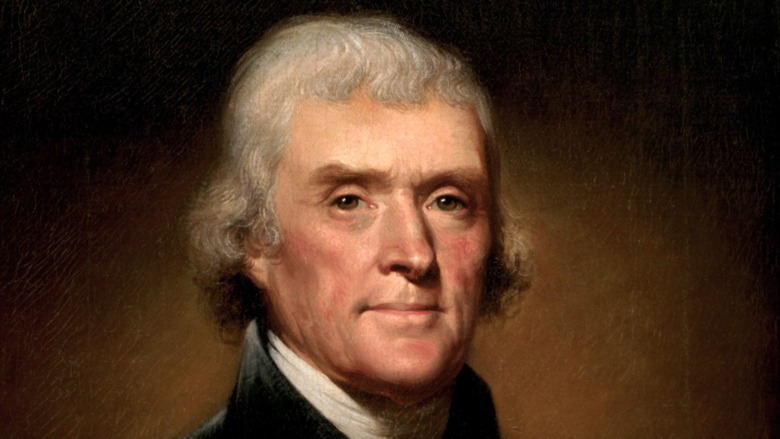

Thomas Jefferson wanted to make it to the Fourth of July

Thomas Jefferson, like Adams and Washington, was one of the key figures of American Independence. Jefferson is famous for being the main author of the Declaration of Independence. As the White House website describes, in his later career, he also served as the third president of the United States and was responsible for the first major expansion of the country with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia describes how Jefferson and his old friend John Adams had split over the election of 1800 but had reconciled starting in 1811. Jefferson, however, not as obsessed with Adams as Adams was with him. Rather, Jefferson felt that his lasting legacy was with the Declaration of Independence and the birth of a new country. As such, as Jefferson's health declined, he wished to survive until the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration — July 4, 1826.

As the former president faded and was bedridden, he struggled to reach the anniversary. According to the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, on July 3, 1826, the former president had slept most of the day and woke up in the evening asking, "Is this the Fourth?" The physician, Robley Dunglison, replied, "It soon will be." Nicholas Trist, Jefferson's grandson by marriage, recorded a slightly different version in which Jefferson repeatedly asked if it was the Fourth, and finally, Trist nodded yes despite his misgivings. Later that night, Jefferson refused to take any more laudanum. However, he made it to July 4, passing away at 12:50 p.m. at age 83.

Andrew Jackson didn't want to be put in a Roman sarcophagus

Andrew Jackson is best known today for being featured on the $20 bill, his anti-Native American policies, and his push for democracy among the lower classes. Called "Old Hickory," he was viewed as rough and tough and was the first populist president in the United States, holding the office from 1829 to 1837.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Jackson remained anti-elite even after the presidency. As his health failed from a lifetime's worth of gunshots and heavy campaigning, he began to think of his death. In 1845, he was so far gone that his associates showed him a coffin — not a regular coffin but a 7 ½- by 3-foot marble sarcophagus worthy of Roman emperors. In fact, it was believed to have once held the bones of the emperor Alexander Severus. They had imported it from Europe. There was a cult of personality around Jackson, and they thought that he would be flattered. Jackson turned down the sarcophagus, writing, "I cannot consent that my mortal body shall be laid in a repository prepared for an Emperor or a King — my republican feelings and principles forbid it — the simplicity of our system of government forbids it." Jackson later ordered, "I wish to be buried in a plain, unostentatious manner."

When Jackson died on June 8, 1845, he was buried at the Hermitage as ordered, though there were thousands in attendance, including his swearing parrot Pol, which had to be removed for squawking some of Jackson's choice phrases.

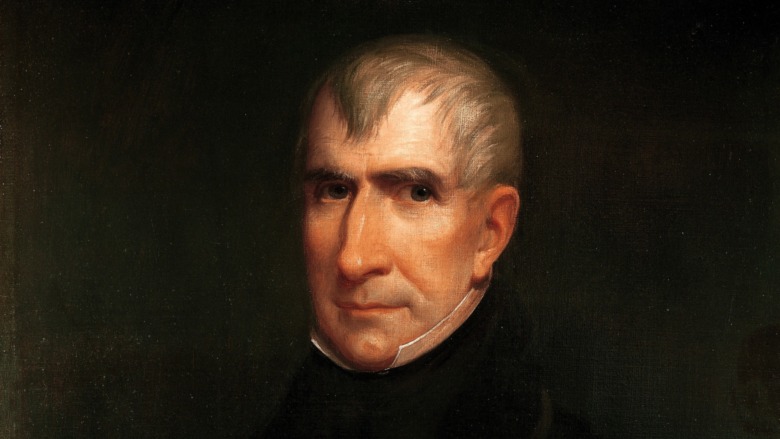

William Henry Harrison seemingly wanted his doctor to know how government worked

William Henry Harrison was briefest-serving president of the United States. As told by the Miller Center, at his March 4, 1841, inauguration, the president gave a speech which, as recorded by Yale's Avalon Project, started with this long-winded sentence:

Called from a retirement which I had supposed was to continue for the residue of my life to fill the chief executive office of this great and free nation, I appear before you, fellow-citizens, to take the oaths which the Constitution prescribes as a necessary qualification for the performance of its duties; and in obedience to a custom coeval with our Government and what I believe to be your expectations I proceed to present to you a summary of the principles which will govern me in the discharge of the duties which I shall be called upon to perform.

The speech was over 8,400 words long. It was, according to Britannica, the longest inaugural speech in history, taking nearly two hours to complete. Harrison gave it without a hat or jacket despite a snowstorm. Harrison took ill and, in three weeks, developed pneumonia. As he lay dying, he made wishes known to his doctor: "Sir, I wish you to understand the true principles of the government. I wish them carried out. I ask nothing more." It is believed that these words were for his vice president John Tyler, who became president after Harrison succumbed on April 4.

James Buchanan wanted people to think he wasn't responsible for the Civil War

President James Buchanan's claim to fame is that he is consistently ranked worst by historians, such as in one list published by C-SPAN in 2017. Why? As explained by the National Museum of American History, Buchanan sympathized with the South and did nothing as the country began its long march toward the Civil War. During his tenure, Burchanan accepted the racist Dred Scott decision, which declared that Black people were not citizens. As tensions mounted between the North and the South, Buchanan declared "the injured States, after having first used all peaceful and constitutional means to obtain redress, would be justified in revolutionary resistance to the Government of the Union." This is coming from the head of that government of the Union!

After Abraham Lincoln's election, the South did secede, and Buchanan was blamed for, if not outright instigating the war, having done nothing to stop it. The retired president undertook a mission to clean up his reputation, even publishing a defensive memoir which stated that he tried to stop the breakup, but Congress wouldn't let him. These self-rehabilitation tomorrow efforts failed, and upon Buchanan's death in 1868, per Tulane University, he took on the infamy of being one of America's worst presidents — ever.

Ulysses S. Grant was dying for a glass of water

Ulysses S. Grant came to fame as a general of the Union during the Civil War who, as described by the White House, was a tenacious fighter who won critical victories such as the one at Vicksburg. He was the general who received the surrender of Confederate general Robert E. Lee at the Appomattox Courthouse. In 1869, he became president and served for two terms during the important Reconstruction years, trying to reunite the North and South. Although his presidency was wracked with scandals, Grant himself was honest and popular and won a second term.

After his presidency ended in 1877, Grant joined a financial firm as a partner. It went bankrupt, and the former president was out of money. Meanwhile, Grant also developed terminal throat cancer. Now facing not only destitution but agonizing death, Grant made a deal with Mark Twain to publish his memoirs. In a final sprint, he finished and published the two-volume set five days before his death. It ended up earning his family $450,000 and getting them well out of debt. As described by The President is Dead!, the last hoarse word the former president uttered as the disease ravaged his throat was "water."

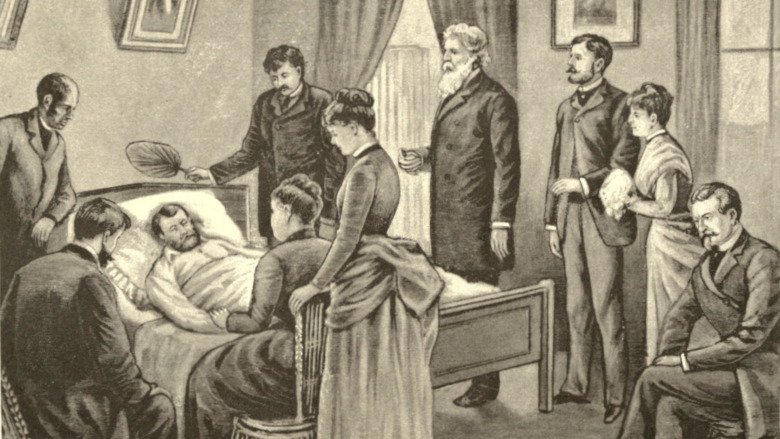

James Garfield just wanted the pain to stop

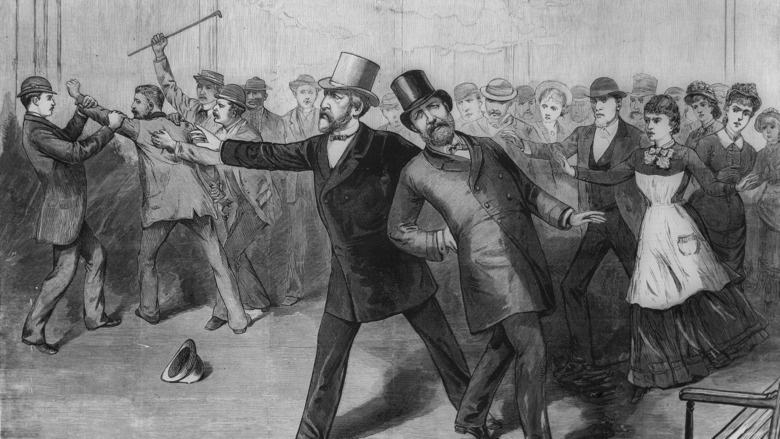

President James Garfield was shot by Charles Guiteau, an insane attorney, at the Baltimore and Potomac Train Station on July 2, 1881. As described by PBS, the first shot grazed his arm, but the second passed through his spine and lodged in his abdomen. The president initially screamed, "My God, what is this?"

Garfield's situation worsened over the coming weeks, mostly because the doctors that treated him insisted on trying to remove the bullet. Because this was in an era before germ theory was widely accepted, the surgeons were not properly sanitized, and Garfield was not kept in completely sterile quarters. As a result, Garfield's wound became badly infected, leading to sepsis. It was agonizing to Garfield, who oftentimes was under no anesthesia during the attempts to surgically widen the hole to remove the bullet. The wound became filled with pus, and the infection spread, all of which meant terrible pain for the president. He wasted away from 210 to 130 pounds.

By the end, Garfield could only talk about the pain. Finally, on September 19, after over two months of torture, the end thankfully came. Garfield probably had the worst death of any U.S. president.

Warren G. Harding wanted to hear just one good article about himself

Warren G. Harding's administration is ranked as one of the worst in American history. As related by the White House, the administration, which ran from 1921 to 1923, was filled with cronies who used their offices to bilk the public. The most notable of these fleecings was the Teapot Dome Scandal in which, as described by Britannica, involved the Secretary of the Interior secretly leasing public lands for private gain. While Harding himself was not implicated in these scandals, he was held responsible. Harding lamented, "I can take care of my enemies all right. But my damn friends ... they're the ones that keep me walking the floors nights!"

On August 2, 1923, Harding was in bed with what was thought to be food poisoning. His wife read to him a supportive article from the Saturday Evening Post entitled "A Calm Review of a Calm Man." One of the quotes which must have impressed Harding was "I think that as an American, as President, and as a human being, the Hon. Warren G. Harding hasn't had and isn't having fair treatment from all this gang of knockers, maligners, self-seeking politicians, disappointed applicants for his favor, theorists and fanatics and fools who want to reform the world in half an hour."

Harding was delighted. He urged his wife, "That's good! Go on — read some more."

Harding got his wish. But then he died suddenly of a heart attack a few minutes later.

Calvin Coolidge wanted to go back in time

Warren G. Harding's successor was Calvin Coolidge. Dour and laconic with a dry sense of humor, he became an emblem of the 1920s for his laissez-faire attitude, small-town values, and his vision of a minimalist government. He was essentially a conservative's conservative and, according to the Miller Center, was a popular president. It was somewhat surprising, therefore, when he chose not to run for office in 1928. In fact, Coolidge never really explained why. However, it was probably due to the premature death of his son, Calvin Jr., from an infection in 1924 as well as for his own desire to retire from office into a quiet life in Northampton, Massachusetts.

There Coolidge remained, even as his successor Herbert Hoover saw the coming of the economic disaster of the Great Depression. Hoover, also a conservative, was viewed as not having done enough to counter the disaster, leading to the landslide victory of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 and the beginning of the New Deal. This would mark the greatest intervention of the federal government in American history. However, this was an anathema to Coolidge, who clearly wanted to return to another time when, as quoted by the White House, he said, "I feel I no longer fit in with these times." Coolidge died shortly thereafter on January 5, 1933, of heart failure. He did not make it to FDR's inauguration.

John F. Kennedy wished to unite the country

President John F. Kennedy was suddenly assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. JFK is remembered for speeches such his inaugural address, his leadership during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and his vision for humans to land on the Moon. One might think that because of the president's sudden death, he wouldn't have any last wishes. However, as reported by CNN, Kennedy was due to make a speech to the Texas Democratic State Committee in Austin that same day. The typed draft of his speech, preserved by the John F. Kennedy Library, remained undelivered. Its ending comments provide a glimpse into what seemed to be a perennial hope for a divided nation:

For this is a time for courage and a time for challenge. Neither conformity nor complacency will do. Neither the fanatics nor the faint-hearted are needed. And our duty as a party is not to our party alone, but to the Nation, and, indeed., to all mankind. Our duty is not merely the preservation of political power but the preservation of peace and freedom.

So let us not be petty when our cause is so great. Let us not quarrel amongst ourselves when our Nation's future is at stake. Let us stand together with renewed confidence in our cause — united in our heritage of the past and our hopes for the future – and determined that this land we love shall lead all mankind into new frontiers of peace and abundance.

Lyndon Johnson wanted a clean reputation

After Kennedy's assassination, Lyndon Johnson became president. As summarized by the Miller Center, Johnson was known for his civil rights legislation, his Great Society programs to fight poverty, and his escalation of American involvement in Vietnam. Of these, the Vietnam War became the defining event of his term and split the nation. After a major offensive by the North Vietnamese showed that the war would drag on, Johnson had become highly unpopular and chose not to run for president again in 1968.

For his post-presidential life, he said, "I'm going to enjoy the time I've got left." However, he was worn out, sick, and bitter. Johnson took up a crusade to protect his reputation. At the same time, he ceased to care about his health, taking up smoking after quitting for decades after a heart attack. As reported by The Atlantic, Johnson claimed unfair treatment by the media. As summarized by PBS, he emphasized to civil rights leaders in 1972 that he had not "done enough." Depressed and alienated, Lyndon Johnson was interviewed by Walter Cronkite on January 12, 1973. This proved to be his last interview, as Johnson died of a heart attack on January 22. Five days later, the Paris Peace Accords were signed, ending the Vietnam War.