The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison was one of the most prominent American writers of the 20th Century, paving the way for Black literature and the community. Working as a writer and editor, she was known as a woman with a brilliant mind but also an honest mouth and a sharp pen.

An award-winning author with honors like a Nobel Prize (as the first African American female writer), Pulitzer Prize, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom from former President Barack Obama, her books are a part of the obligatory curriculum in the American education system. Novels like "Beloved," "Song of Solomon," "Sula," and many others told numerous stories of the reality of Black people and the Black community in the U.S., throughout history to the present day (via Britannica).

Morrison's life wasn't easy, as racism was always present, even if she dealt with it in her own way through writing. Growing up in poverty, she was the best student in her class, working as an English literature professor for a while. As a divorcee with two small children, she took a full-time job as an editor while writing her first novel at night. She had to battle prejudice, ignorance, and pure spite when she introduced her raw, honest stories full of truths people would prefer not to hear. She took it all with dignity and integrity, staying persistent in her demands for great knowledge and impeccable writing (Via The New Yorker).

This is the tragic real-life story of Toni Morrison.

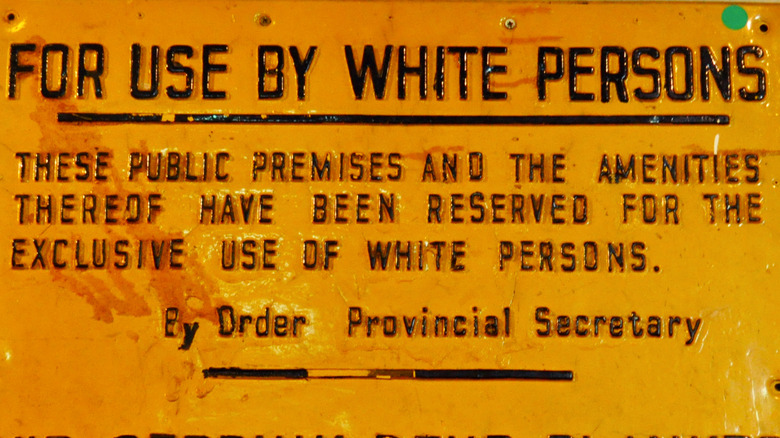

Trauma of racism was embedded in her family

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford, choosing her nickname Toni later in life, after Saint Anthony. She grew up in the steel town of Lorain, Ohio, where poverty was ingrained in Black and white communities equally. Segregation, however, wasn't something she experienced as a child, New York Magazine has reported.

Her parents, Ramah, and George, had experienced racism, and her father was particularly wary of white people to the extent that he wouldn't let them in their family home. After many years of personal and systemic racism, including observing lynchings as a teenager, he thought white people were like "Nazis — true demons." Her mother, on the other hand, didn't see all white people as a united group, she divided them according to their actions. Nevertheless, she always fought against any kind of segregation, as an individual refusing to move. As Morrison recalled for The Guardian, they both taught her a great deal about being proud of who you are and not feeling less worthy due to her skin color.

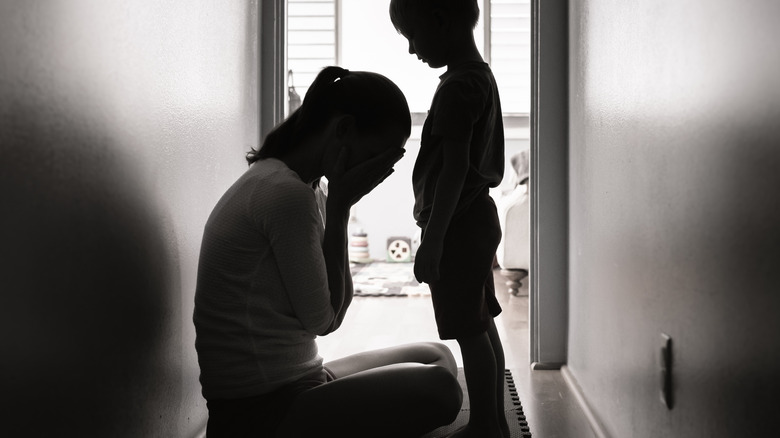

But, as she told Zia Jaffrey for Salon, raising two sons on her own was hard, and she wasn't sure if she communicated racism to them correctly. Morrison always saw racists as "intellectually and emotionally deficient" individuals, and as a woman, she learned how to ignore them from a young age. Men feel and experience racism differently, and she couldn't protect them from that.

She experienced a house fire twice

One of the most horrific encounters with racism happened when Toni Morrison was a child when the landlord set their home on fire because the family couldn't keep up with the $4 monthly rent. As a result, Morrison's family moved around a lot — and even moved at least six times while she was a child, reported Hilton Als for The New Yorker.

The second fire that struck Morrison's home took place when she lived with her two sons in New York's Rockland County. Morrison said that sometime around Christmas in 1993, fire from the family home's fireplace spread out to nearby dried Christmas tree needles and further into the living room. The flames, she said, completely devoured the furniture as they tore through the family's home. One of her sons was at home alone, and he did call the fire brigade, but cold winter had frozen the area's water lines and restricted access to fire-extinguishing water. Morrison said that she lost all of her original manuscripts — which she said didn't mean much to her at the time — but would have served as historical documents in the future. What hurt her deeply, Morrison recalled, was the loss of her photo albums, letters, school reports, and other personal items, which reminded her of her family. The original editions of Emily Dickinson and Faulkner were gone as well, along with 40 other books (via Salon).

She faced racial segregation as a student

It wasn't until Toni Morrison started her studies at Howard University, a leading HBCU in Washington, D.C., that she was presented with real segregation for the first time in her life. High schools were segregated, as well as bus seats, but segregation appeared on her campus, too, despite the fact that the university was open to all. The students often reportedly conducted what was widely known as "the paper-bag test," in which they allocated the students according to how similar their skin tone was to the color of the paper. Those whose skin tones were much lighter than a standard light brown paper bag were the most privileged students, the concept which Morrison labeled as"idiotic preferences." The author said that she ended up focusing her energy on the drama department in the institution, as they apparently preferred talent over racial measurements (via The New Yorker).

But as Morrison told Christopher Bollen for Interview magazine, Howard University, where she studied English literature, and its curriculum wasn't focusing on African-American writers either — or African-Americans at all. On the contrary, when she suggested she would write a paper on Black people in Shakespeare, her idea was dismissed as "a low-class subject" and something not worthy about which to write.

She divorced her first husband while she was pregnant

Toni Morrison met her former husband, a Jamaican architect named Harold Morrison, in 1958. But the marriage didn't last, and the couple eventually divorced in 1964 when Toni was pregnant with their second child (via Encyclopaedia of World Biography).

The author never did speak much about her divorce, but she did mention a few details of what transpired in the couple's marriage, as reported by New York Magazine. It seemed, the outlet reported, that Morrison's former husband wanted someone who would be more subservient and less opinionated. "He didn't need me making judgements about him," Morrison said. "Which I did. A lot."

Divorce, she reasoned, isn't something of which one should be ashamed, as she told Salon. Morrison added that she believed women can learn a lot from such experiences, and grow in unprecedented ways. "We should stop thinking about these encounters — however long they are, because they do not last — as failures," she explained. "When they're just other things. You take something from it." The author never did marry again, although she didn't reject the idea of marriage completely. Morrison added that she still believed that having both parents present was the best for children, but not as an isolated unit — what she valued most was a big family with many family members.

She had no time for writing, but she did it anyway

After her divorce, Toni Morrison took a full-time job as an editor at Random House publisher. While raising her two sons on her own, she decided it was time to write her first book, "The Bluest Eye." With an iron discipline, she squeezed her writing hours around the other chores, waking up extremely early, writing through weekends and during summer while her kids were at their grandparents' home in Ohio. Speaking about how she did it for Salon, Morrison highlighted how she used every second of her time thoughtfully, thinking about her literary characters while she was doing the dishes or riding a subway.

As Morrison explained in Interview magazine, the time of writing represented complete freedom to her, as she wasn't told by anyone what to do. "That was my world and my imagination," she reasoned. Morrison added that she completely omitted the white male gaze, often internalized by other Black writers and white women; she didn't look at the world through "the master's gaze" in her writing. Morrison added that she didn't feel she needed to prove anything but was learning about the world and other people's internal experiences solely through asking the right questions, not by asking someone else — she asked herself what she thought of the matter. Along with writing, rereading her creations was also an important part of the task; that is how she developed the intimacy present in her work.

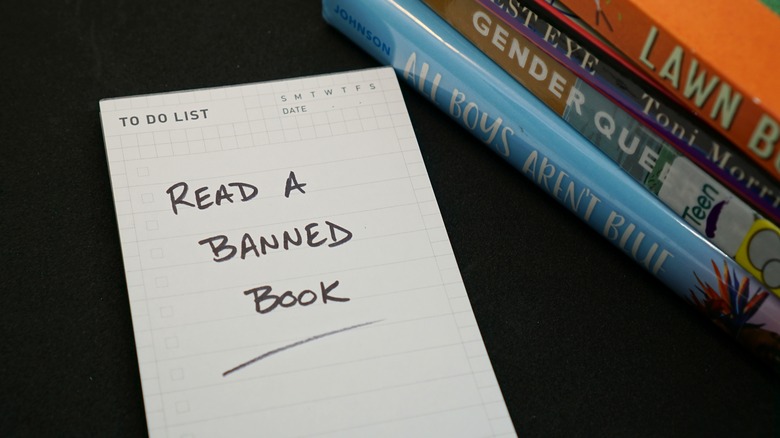

Her work wasn't always well accepted by the Black community

Toni Morrison said that her very first novel, "The Bluest Eye," wasn't immediately accepted by publishers or the Black community. Because she wanted to omit the white gaze completely, Morrison said that she was brutally honest about these feelings, writing a book about a Black girl Pecola Breedlove, who wanted, more than anything, to have blue eyes. The revered author said that the story was ultimately based on the true account of a girl she once met when during her younger days.

In her later novels, Morrison would go on to demolish the idea of the Black union as a community that always stuck together. Instead, Morrison addressed the violence inside the community, just as it takes place anywhere else. Describing raw situations where people were good and evil at the same time, Morrison refused to idealize anyone, and this, for many, she said was far too much —and reasoned that this was the very reason those critics rejected her work (via The New Yorker).

One of the Black critics who heavily criticized Morrison's work was Stanley Crouch, calling her "a literary snake-oil saleswoman" who writes sentimental melodramatic TV scenarios tainted with ideology (via Salon).

The driving force behind her work was pain

Toni Morrison often based her novels on real-life news articles, as these stories spoke to her through the lens of her own experience and struggle. Her most recognizable novel, "Beloved," is based on The Margaret Garner Incident from 1856. Born into slavery in Kentucky, Margaret had four children with Robert Garner. When they tried to flee slavery and escape to Canada, they sought refuge in Cincinnati, where they were stopped by their master, A.K. Gaines, and federal marshals. Instead of giving in, Margaret tried to kill her children, managing to slit her 2-year-old daughter's throat, wounding the rest (via Black Past).

Revealing to Interview magazine how she found this story, Morrison discovered the news clipping while she was working on "The Black Book," a book on Black history in the U.S. What drew her into the story, she said, was the subtext of the event: a Black woman owning her children by not letting them be sold into slavery, the opposite view of prevailing feminist views of the time, and who fought to be able to decide about their fate by accessing abortion care on their own terms.

Throughout life, Morrison had to come to terms with a lot of anger stemming from the brutal and unjust conditions she and other Black people had to endure. But as she told Salon in 1998, she lost this anger throughout her life — and said that what remained was sadness.

Despite the quality of her work, she was often dismissed

When Toni Morrison wrote "The Bluest Eye," she was reportedly dismissed by publishers. The book was printed in 1,200 copies by Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, in a paperback edition — "a throw-away book," as she told Interview magazine.

Deriving from the oral tradition of storytelling, her novels were lyrical and intense, inviting the reader deep into the literary world. Her revealing stories disturbed many, who couldn't help to publicly diss her work. When she was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1993, critic Stanley Crouch commented that the award might help inspire her to write better books. Others concluded the award was "a triumph of political correctness." But others supported her immensely.

As Morrison explained to Salon, a racist perspective on anything that diverged from the norm — including her writing — existed. Morrison's critics, she said, were often lazy in the sense that they revealed excruciatingly poor knowledge of literature and sociology. She added that she believed Black people were regularly portrayed as irrational, emotional, and crazy — unsuitable for white standards. Morrison said that the cultural elements of her writing were diminished as post-modernism and weren't recognized as a traditional, valid way of storytelling.

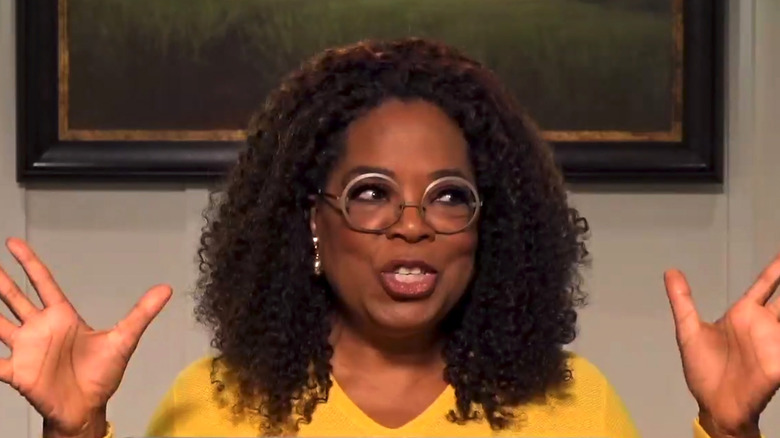

It took TV star Oprah Winfrey to popularize Morrison's literature

Professor John Young in Marshall University's Digital Scholar said that the white publishing industry has long — and frequently — neglected its Black writers. There were periods, Young said, when Black authors briefly trended, as took place in times such as between the 1920s and 1930s, and once again between the 1960s and 1970s. But these periods, he said, didn't accept Black writers as they were and instead attempted to capitalize on and further cement stereotypes surrounding the Black community.

Media mogul Oprah Winfrey, on the other hand, was said to help break this very pattern by promoting Toni Morrison's literature, which was already canonized by academic and critical spheres. The "Oprah Effect," as Young called the phenomenon, enabled Morrison to reach a far wider audience than if connoisseurs and students only read her books. After Winfrey included several of Morrison's books in her Oprah Book Club and hosted the author on her hit daytime TV show, a few of Morrison's novels became best-sellers.

She lost her son to cancer

Slade Kevin Morrison, Toni Morrison's second-born son, died from pancreatic cancer in 2010 at the age of 45. Slade, she said, was an abstract painter and also collaborated with his mother on no less than eight children's books including "Little Cloud and Lady Wind," "The Lion or the Mouse?" and even more (via Heavy).

Slade's death deeply affected the author, and she told New York Magazine that for months, she couldn't even write, and stopped right in the middle of writing her novel "Home." The revered author and social critic added that she regretted not being able to save her son, whose death she recalled seeing as a consequence of his disregard for western medicine. The pain never went away, the author continued, and said that the untimely death of her beloved son "clouded everything, everything, everything, everything." "It'll be with me like a shroud, or a cape, forever," she admitted. Morrison would go on to dedicate "Home" — which she ultimately completed after her son's death — to the memory of the late child.

Her strong connection to the afterlife was derived from painful life experiences

"Beloved," as well as other Morrison's novels, incorporate many folk spiritual beliefs, creating a magical realistic literary style. The African-American legacy with its rich plethora of stories about the intangible, ghosts, and rituals, helps to turn stories into a mythical landscape. As Morrison explained to Pip Cumming for The Sydney Morning Herald, she had a near-death experience while she was midway through life. Morrison spoke about how she left her body, but said that she still had an acute consciousness and was able to see. Morrison recalled being able to move around the neighborhood and was even able to observe life on the street. She didn't want to return to her body, she said, but felt responsible for her sons, so she re-entered her body once more. It wasn't easy, as the peace she felt while she was unconscious was apparently far better than anything she felt through life, she explained. "It was free, it was intelligent, and I was in control. And the only other time that happens — those three things — is when I write."