People Who Didn't Get Credit For Helping Write Classic Rock Songs

By its very nature and definition, playing in a band is a collaborative effort. As far as mid-20th century rock bands go, they were all about a small and tight-knit group of creatively like-minded people sharing a common goal and working toward it: to totally rock out and please their adoring fans in doing so. While writing songs had once been the domain of dedicated composers and lyricists who worked in musical factories like New York's Brill Building (according to Britannica), by the mid-1960s, bands were writing their own songs, generally with one or two people in the group doing most of the heavy lifting — but not always.

Due to the vagaries of the music business, greed, selfishness, or the strange and unpredictable ways in which art can be made, credit is not always given where credit is due. Songs can become huge hits, sell millions of copies, and make their way onto classic rock radio stations' permanent playlists without the general public or the biggest fans of the acts that made them aware of the real truth of their composition. Here are some of the most popular rock songs from the days of yore with secret or unheralded contributions from writers who didn't get the plaudits.

The second half of Layla may have been stolen from Rita Coolidge

After stints with the Yardbirds, Cream, and Blind Faith, guitar giant Eric Clapton formed Derek and the Dominos in 1970, and that year released its only studio album, "Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs," featuring the title tune "Layla." The seven-minute epic arrives in two parts: the first is a hard-charging guitar jam, and the second is an emotional instrumental carried by the piano of Jim Gordon, Derek and the Dominos' drummer.

The songwriting credits for "Layla" list Clapton and Gordon; Clapton for part one, and Gordon for part two. But Gordon might have stolen the bulk of that second section from his former girlfriend, '70s soft rock star Rita Coolidge, who heard "Layla" on the radio one day and recognized the coda. "The song on the radio was my song — except that I'd never recorded it," Coolidge wrote in "Delta Lady." The "Layla" portion was identical to "Time," a song she and Gordon wrote together. When she got a hold of the album and found she wasn't credited, she was livid and took the issue to record executive David Anderl and Clapton's manager, Robert Stigwood. Anderle pointed out that Coolidge didn't have the cash to legally pursue her claim; Stigwood reportedly told her, "You're a girl singer — what are you going to do?"

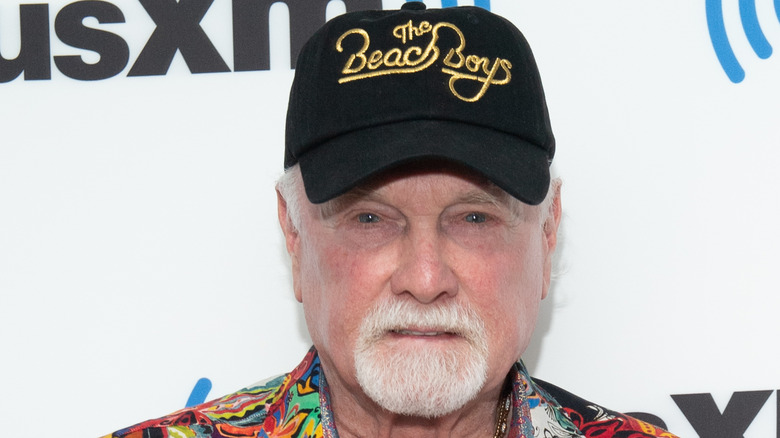

Authorship of The Beach Boys' Surfin USA is disputed

The Beach Boys were a family band, featuring brothers Carl, Dennis, and Brian Wilson and their cousin, Mike Love. The Wilsons' father, Murry Wilson, served as their manager and then ran their publishing company, handling the rights and financials of their songs.

According to the Los Angeles Times, Brian Wilson received a settlement of $10 million in 1992 after alleging that Murry Wilson fraudulently coerced him into giving up his rights to The Beach Boys catalog, which he then sold to Irving Music for $700,000. On the heels of that suit, which restored copyrights to Brian Wilson, Love sued Murry Wilson in 1994, seeking a third of the $10 million settlement and alleging he'd also unfairly missed out on songwriting royalties. Love claimed he'd gone unrewarded for helping to write 79 of The Beach Boys' songs.

He won the suit, sort of, and was granted songwriting credit on 35 of The Beach Boys' tunes, per the Los Angeles Times. That included "Help Me, Rhonda," "I Get Around," and "California Girls," according to the Herald Tribune. One of the songs by The Beach Boys that Love claimed to have helped write that he didn't get his name on was "Surfin' USA," his band's first top 10 hit issued in 1963. In a 1974 radio interview with KRTH, Love's contributions to that song's lyrics were explained by none other than Brian Wilson.

Eddie Van Halen 'Beat It' to the studio and knocked out a solo

Part of the reason why Michael Jackson's "Thriller" became the best-selling global album of all time — with 67 million copies sold, according to Guinness — is because there's a little something for everyone on that crowd-pleaser of a record. There's pop, soft rock, soul, dance, R&B, and with "Beat It," hard rock driven by some loud and heavy guitars. Toto's Steve Lukather played the song's main guitar part, but the unhinged solo was the work of the hard rock legend of the moment, guitar wizard Eddie Van Halen of Van Halen.

Producer Quincy Jones called Van Halen to ask him to do it. Van Halen thought it was a prank call until he figured it out and agreed to contribute to what he'd been told was just some new Jackson song. While Jackson was away the next day, Van Halen went into Jones' studio, heard a rough cut of "Beat It," offered some tips on how to arrange the song, and then recorded two guitar solos — back to back and completely thought up on the spot. He was in and out of the studio in half an hour, according to CNN. Van Halen didn't even accept payment for playing the song, considering it a favor to Jones.

One Grand Funk Railroad member got jipped on We're an American Band

They're rarely mentioned as one of the most important rock bands of the 1970s, but Grand Funk Railroad (or just Grand Funk) was certainly among the most popular. Between 1969 and 1974, the hard rockers released 10 albums, and all of them were certified at least gold by the Recording Industry Association of America. In 1971, the band sold out a show at New York's Shea Stadium in 72 hours (per UCR). Grand Funk topped the Billboard pop singles chart twice with a cover of "The Loco-Motion," and "We're an American Band."

Drummer Don Brewer is the only member of Grand Funk to get a songwriting credit on "We're An American Band," but that's not fully accurate. "He wrote the lyrics," singer and guitarist Mark Farner told SongFacts, adding that he came up with the rhythm for the melody, the idea to use a cowbell, the introductory drum flourish, chord changes, and backing vocal arrangements.

Brewer got full credit because he asked. Farner recalled Brewer telling him, "I've never had 100% writing credit on any song. Do you mind if I take it on this one?" Farner felt for him and gave up his cut. "And I kind of half kick myself in the butt for it at times over the years, but really my heart was: I'm a nice guy and I'm not going to let life screw it up."

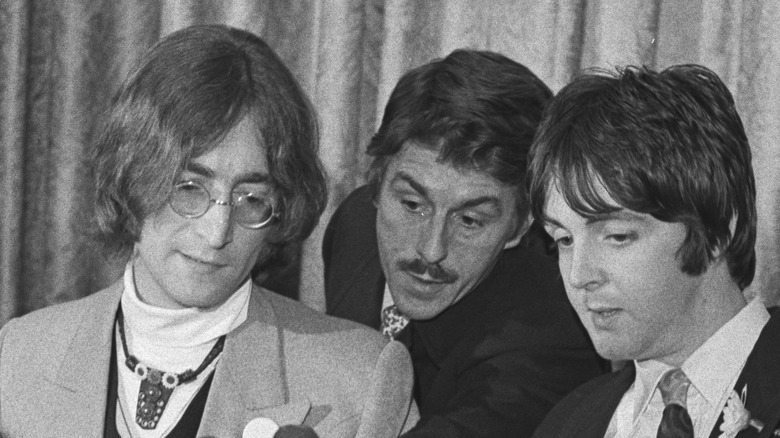

Happiness is a Warm Gun was inspired by a Beatles employee

According to NPR, the writing credits on about 200 of the Beatles' songs jointly went to Paul McCartney and John Lennon owing to an agreement they made earlier in their careers. They often wrote songs alone, but the Lennon-McCartney credit remained strictly intact for business and contractual reasons. That means that other contributors would be left out of the credits, and thus the substantial royalties. Derek Taylor, the publicist for the Beatles' vanity label, Apple Records, is not listed as a contributor, but was responsible for the first part of the lyrics on the meandering progressive rock-influenced "White Album" track "Happiness is a Warm Gun," as they're things he and Lennon said while under the influence of LSD, according to "A Hard Day's Write."

"She's well acquainted with the touch of the velvet hand" allegedly came from Taylor telling a story about a man he met in a bar who told him, "I like wearing moleskin gloves, you know. It gives me a little bit of an unusual sensation when I'm out with my girlfriend." Meanwhile, "Like a lizard on a window pane," was something Taylor saw when he briefly lived in California, and "The man in the crowd with the multicolored mirrors" was from a newspaper article Taylor had seen about a Manchester soccer fan arrested after placing mirrors on his shoes to peek up skirts."

'Imagine' that John Lennon took an idea from Yoko Ono

For decades, Yoko Ono struggled to get both respect and credit for her music. Many Beatles fans blame the experimental artist and musician for splitting up the band, theorizing she possessed an overwhelming influence over her husband John Lennon (per NBC News). Ono has recorded a lot of music, scoring a number of hits on Billboard's dance chart, and was responsible for half of "Double Fantasy," her joint 1980 LP with the late Lennon that won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year. A decade earlier, Lennon and Ono joined forces for the Plastic Ono Band, and Lennon's gentle, hymn-like call for world peace, "Imagine," was officially credited to Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band, with Lennon the sole listed songwriter.

At a 2017 event held by the National Music Publishers Association in which "Imagine" received the "Centennial Song" award, the organization's top executive David Israelite surprised the audience, which included Ono and her son Sean Lennon, with the announcement that Ono would from then on be a credited writer on the song (per Billboard). Israelite played a clip of a '70s BBC interview with John Lennon talking about "Imagine": "Actually that should be credited as a Lennon-Ono song because a lot of it — the lyric and the concept — came from Yoko," he said. "But those days I was a bit more selfish, a bit more macho, and I sort of omitted to mention her contribution."

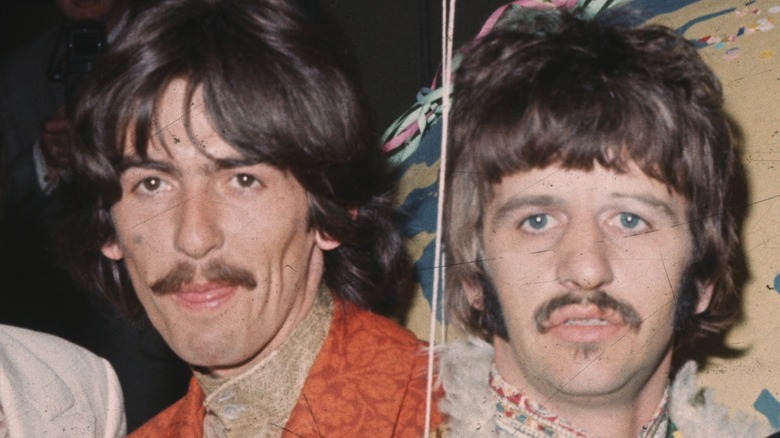

Ringo Starr's It Don't Come Easy came with a little help from his friend

According to History, the Beatles' breakup became official when Paul McCartney announced that the band had parted ways. But while all four musicians would never play together all at once ever again, they frequently helped out on each other's projects over the years. For example, Ringo Starr played drums on George Harrison's 1970 solo album "All Things Must Pass," and Harrison produced and co-wrote two of Starr's biggest early '70s successes: the No. 1 smash "Photograph (per "The Billboard Book of #1 Hits"), and the No. 4 hit "It Don't Come Easy." Harrison is a credited songwriter only on "Photograph," but he had a heavy hand in the composition of "It Don't Come Easy," as well.

Something of an open secret in Beatles lore, the idea that Harrison co-wrote "It Don't Come Easy" appears in authoritative sources on the band, and on his 1998 episode of the sing-the-tune-and-explain it VH1 show "Storytellers" (via SongFacts), Starr confirmed as much. "I wrote this song with the one and only George Harrison," he said. "We wrote it in the early '70s." However, Starr (under his real name, Richard Starkey) is the only songwriter listed on the song's 45 label.

A Whiter Shade of Pale co-writer got credited 40 years after the fact

Amidst the psychedelic rock and hippie-folk sounds of the time, not much on the radio sounded quite like "A Whiter Shade of Pale" upon its release in 1967. The esoteric lyrics — such as "We skipped the light fandango / turned cartwheels 'cross the floor" — and melodies reminiscent of Bach and baroque music with the organ as the dominant instrument made for an irresistible combination. This anthemic tune by the English band Procol Harum hit No. 1 in the U.K. and No. 5 in the U.S.

In the late '60s, a man named Matthew Fisher ran an ad in the British musicians' magazine "Melody Maker," advertising his services as the owner and operator of a Hammond organ, according to The Guardian. Procol Harum responded and brought him in to play on "A Whiter Shade of Pale," adding the organ riff he wrote to the song. In 2005, Fisher, tired of never being recognized for his unacknowledged work on a well-known song, filed suit. Four years of lawsuits and appeals later, Fisher was legally recognized by the House of Lords as a royalties-entitled co-writer of "A Whiter Shade of Pale," alongside band members Gary Brooker and Keith Reid.

Prince helped Stevie Nicks record Stand Back

After ascending to the top of the musical world in the 1970s with Fleetwood Mac, Stevie Nicks launched a solo career in the early 1980s. On her own, Nicks was versatile, from the arena rock of "Edge of Seventeen," to the synthesizer-driven "Stand Back." The label for "Stand Back" lists just one songwriter: Nicks herself. But she didn't come up with everything — Prince both inspired and contributed to "Stand Back."

While driving with her then-husband Kim Anderson, Nicks heard Prince's "Little Red Corvette" on the radio. "All of a sudden, out of nowhere, I'm singing along, going, 'Stand back!'" she told Ultimate Classic Rock Nights (via UCR). "I'm like, 'Kim, pull over! We need to buy a tape recorder because I need to record this.'" They did, and then the newlyweds stayed up late into the night working on this new tune. Nicks explained that she leaned heavily on the same instrumentals and melody that Prince's song had, but what set her song apart was the lyrics.

When it came time to record the song at the Sunset Sound studio in Hollywood, Nicks called Prince and asked if he wanted to come down and hear it since half of it was basically his song. To Nicks' surprise, Prince came right over, listened to the demo, and then played all the keyboard parts, inventing them on the spot. "That was the coolest thing we ever heard," Nicks recalled.

I Want to Know What Love Is was a Foreigner collaboration, not a solo effort

After cranking out radio-friendly, fist-pumping arena rock in the '70s and early '80s, Foreigner switched it up to become a master of the power ballad — soaring slow songs bursting with rock energy to proclaim feelings of romance and yearning. In 1984, Foreigner hit No. 1 on the Billboard pop chart with "I Want to Know What Love Is." Unlike a lot of Foreigner's singles, the tune was credited only to Jones, and Gramm rejects the notion that his bandmate came up with their biggest hit all by his lonesome, telling The Sessions (via Blabbermouth) that his contributions went unattributed and unrewarded.

Gramm said that he and Jones would go through an album's worth of songs and work out who wrote what percentage of each song to set up the royalty rates. They did that for "I Want to Know What Love Is" and Gramm suggested a 65-35 split in his favor. Meanwhile, Jones countered with a 95-5 cut in his favor. "I was so stunned and crushed that he'd think I contributed next to nothing to that song," Gramm said, adding that he was so insulted by the paltry sum, he told Jones to forget it and just take the full 100%, thinking that would start a negotiation. That didn't go as planned, and Jones ended up taking him up on it without another word.

Terry Jacks gave Seasons in the Sun a last-minute rewrite

Canadian folk-rocker Terry Jacks scored a No. 1 Billboard hit in 1974, an unlikely achievement because "Seasons in the Sun" wasn't the typical '70s pop-rocker. According to Song Facts, it was based on a sappy French song from the early '60s and had been rejected by The Beach Boys. French composer Jacques Brel wrote it as "Le Moribond" (or "The Dying Man") in 1961, and American poet Rod McKuen — phenomenally popular in the '60s, and '70s and selling tens of millions of books and albums, per Slate — translated it into English in 1964. The Beach Boys then invited Jacks to a 1973 recording session and got them to lay down "Seasons in the Sun," but they opted to shelve it.

After mourning the sudden death of a friend later that year, Jacks went into the studio and recorded a solo version, but not before revising the lyrics and making the final verse of the song about a wistfully nostalgic dying man a bit more lighthearted and optimistic. "Seasons in the Sun" reached No. 1 in multiple countries, with Jacks credited as the performer but never as a co-writer — only Brel and McKuen got that.