Things That Don't Make Sense About The Hiroshima And Nagasaki Bombings

If there's a topic that needs little introduction, it's probably the atomic bomb. Just because the bombings of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are well known doesn't necessarily mean that everything about them makes complete sense, however.

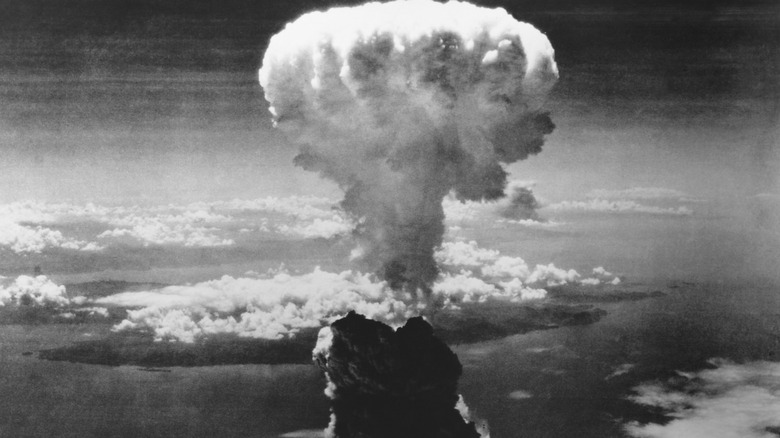

The basic facts all have good standing. Throughout World War II, a group of American scientists and engineers worked together on the top-secret Manhattan Project, studying nuclear fission. By the middle of July 1945, a successful test of a plutonium bomb meant that the weapon was ready for deployment — too late for use in the European front of World War II, with Nazi Germany having already surrendered, but just in time for the Pacific front, where Japanese forces continued to fight. Military officers called for President Harry Truman to make use of the bomb, favoring a show of military might over a costly invasion of Japan, and Truman ultimately agreed. A number of target cities were selected and Hiroshima and Nagasaki were ultimately settled on, with the former being attacked on August 6 and the latter facing the same fate just three days later. Between the initial blasts and the long-term results of radiation exposure, tens of thousands of Japanese people — many of them civilians — died, with estimates ranging as high as some 200,000 deaths.

That's the story as it's popularly known, but when you start digging into the details, then the narrative gets considerably stranger; here are a few of those strange details.

The Soviet Union, not the atomic bomb, might have ended the war

The typical narrative is that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended World War II. On the surface, that seems consistent; Hiroshima was attacked on August 6, Nagasaki on August 9, and Japan surrendered on August 15. But on August 8, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and that act might be what truly pushed Japan to unconditional surrender.

For context, the Soviet Union and Japan had entered into a neutrality pact in 1941 — beneficial to both countries in that it allowed both of them to focus on fewer fronts during World War II. Once the U.S. began gaining momentum in the Pacific, Emperor Hirohito personally reached out to Joseph Stalin, asking him to act as an intermediary between Japan and the U.S. But as the war with Germany turned in favor of the Allies, Stalin warmed to the idea of joining in the war against Japan, even though the neutrality pact was technically still in effect. As such, the Soviet invasion of Manchuria was nothing less than a betrayal.

In just under a week, the Soviet army was moving on three different fronts against Japan, even finding success in areas of significant resistance. In discussions with his cabinet, Hirohito explicitly mentioned the Soviet Union in relation to surrender: "The military situation has changed suddenly. The Soviet Union entered the war against us ... Therefore, there is no alternative but to accept the Potsdam terms" (via The National Archives).

Hiroshima and Nagasaki might have been bombed needlessly

President Harry Truman is quoted as saying, "It was a terrible decision. But ... I made it to save 250,000 boys from the United States" (via USA Today). In general, government officials believed the bombs were a necessity, a way to avoid a far more costly invasion. As such, traditional narratives credit the atomic bomb with ending World War II, but some historians have since claimed that the bombs didn't need to be used. New analyses have claimed that Japan was ready to surrender before the bombing of Hiroshima.

There are two main pieces of evidence for this school of thought. One was a personal piece of correspondence penned by Emperor Hirohito and sent to Joseph Stalin, asking that the Soviet premier act as an intermediary in negotiations between Japan and the U.S. But Stalin received this letter before leaving for the Potsdam Conference (the meeting between Allied leaders regarding the end of World War II), which took place from July 17 to August 2. Hiroshima wasn't attacked until August 6 — an apparent argument that Japan was already prepared to discuss surrender. The other piece of evidence is a study called the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, which found that Japan would have likely surrendered before the Allies could invade, before many of the casualties that U.S. officials feared.

It should be noted, though, that historians heavily debate these points, undecided as to whether or not Japan would have surrendered before the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb.

Japan might have just been looking for an excuse to surrender

What exactly ended the Pacific front of World War II is more a question of debate than most people would likely expect. While the well-known narrative is that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki pushed Japan to surrender, the reality might be a lot more convoluted than that. In a twisted way, the atomic bomb might have been exactly what the Japanese government wanted.

Some historians have looked at Japanese internal records and determined that government leaders were genuinely afraid for the stability of their nation. The war — and all the difficulties that came with it, whether rationing or casualty counts — had left the Japanese people with bitterness toward their leadership. There was a very real chance that the unrest would push extremist groups to revolt, and none of that was helped by the fact that the concept of surrender went against the widely held beliefs that the government had spent much of the war perpetuating. Surrender wasn't an option; at least, it wasn't one that wouldn't come without major political consequences.

So it's possible that the atomic bomb might have provided a morbid — but convenient — out. Surrender in the face of potential nuclear destruction would be seen as more than justifiable, and it wouldn't tarnish the reputation of the Japanese government in the eyes of their people. All of that said, however, it's nearly impossible to know whether that was true, and historians can only speculate.

The intended audience for the bombs is a complicated question

Given that the two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, you'd think that the country the U.S. intended to intimidate was pretty obvious: Japan. But the real truth behind that narrative is rather murky.

With the Soviet Union on the rise, the end of World War II might be better analyzed as the start of the Cold War, as American leaders began exerting pressure on the Soviets. Though nuclear research had previously been kept secret from the USSR, Harry Truman changed that policy to reflect the new circumstances: The Soviets were poised to affect the balance of power in East Asia. The U.S. preferred that the USSR be given as little power as possible in that situation, so Truman let it slip that American scientists had developed a uniquely deadly weapon — a fact that historians now know had Joseph Stalin fairly concerned.

That situation — along with indications that Japan would have surrendered without the atomic bomb — has prompted a reevaluation of the reasons why the bombing was ordered, and some historians argue that the intimidation of the Soviet Union was a significant factor. Dropping the bombs might have been more of a show of power than of military strategy, thus giving the U.S. a stronger bargaining chip when it came to postwar negotiations. All that said, it's impossible for historians to be certain, with nuclear policy at the time being incredibly secretive and largely undocumented, so the truth might be lost to time.

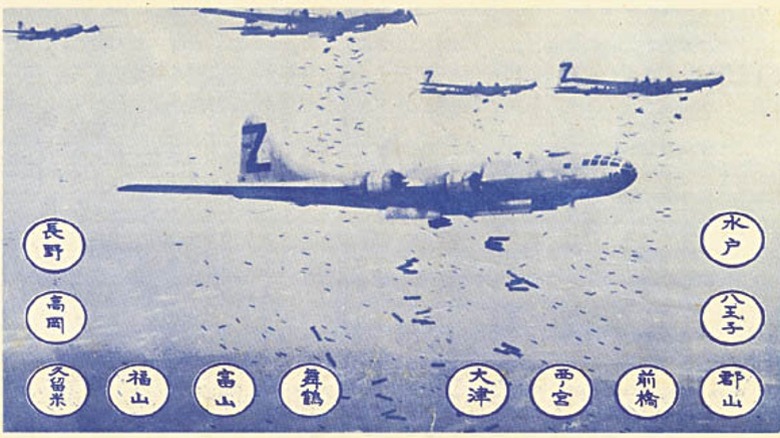

The evacuation pamphlets had questionable effects

Prior to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the U.S. did technically take precautions to warn the civilian populations of their target cities, air dropping pamphlets that urged the Japanese people to pressure their government into surrender, making mention of an incredibly powerful weapon that they would face if the war continued. On the surface, that would seem like enough to say that the U.S. attempted, at least, to limit civilian casualties — a humanitarian act. But later studies have led to some debate as to whether they were helpful.

The pamphlets themselves contained intimidating images of American military might, as well as lists of cities that might be targeted for attacks. A reported 33 cities received at least one of the three versions of the pamphlet, each of which had a slightly different list of target cities. However, the part that's particularly confusing and casts the biggest question over the humanitarian nature of the pamphlets is the fact that neither Hiroshima nor Nagasaki were among the named cities. Their citizens were entirely unaware that an attack was imminent, with reports from Hiroshima even explaining that the locals just thought it a beautiful, normal day. Even if you look outside of those two cities, others were firebombed or otherwise attacked weeks later, having never been named.

Arguably, the pamphlets only made the situation worse, with experts explaining that the threat of lethal force only led to increased chaos, which was the perfect breeding ground for more casualties, not less.

The U.S. military was ready to make more bombs

With hindsight, it's easy to see that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki might have been even worse than people originally thought; it's impossible to deny the reasons many have cited when calling for the end of nuclear weapons entirely. The fact that the bombs would prompt feelings of shock and terror is something of a given in the modern day. But that wasn't the case during the war, difficult as that is to imagine.

Scientists close to the project actually made a prediction about the atomic bomb's effect in a 1946 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (via Carnegie Endowment) — a prediction that would prove to be rather incorrect. In their own words: "It is doubtful whether the first available bombs, of comparatively low efficiency and small size, will be sufficient to break the will or ability of Japan to resist." They believed that, in this situation, the atomic bomb wouldn't cause much more psychological damage than the normal bombing already taking place at that point.

In keeping with that assessment, the U.S. military was actually ready to keep making and dropping even more bombs — indefinitely, in fact. Shortly after the bombing of Nagasaki, military officials continued to make active plans for further attacks, including an outline that would include seven more bombs deployed by the end of October of that year. They were even planning the infrastructure needed to produce bombs consistently, at the rate of at least three per month.

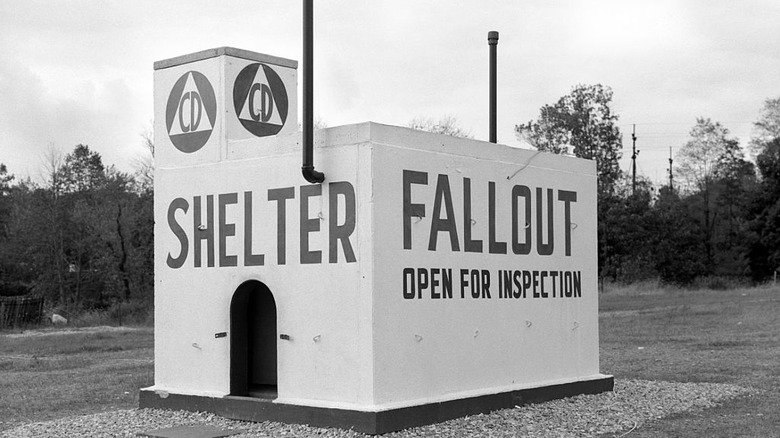

The Cold War might have been avoided entirely

With nuclear warfare suddenly becoming such a prominent — and lasting — threat since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it's hard to imagine a cavalier treatment of said threat. As irresponsible as that stance may seem, it was far from unrealistic, though. In the 1946 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (via Carnegie Endowment), despite simultaneously arguing that the atomic bomb wouldn't be particularly effective in pushing Japan to surrender, scientists also recognized that the deployment of nuclear weaponry during wartime would have serious repercussions when it came to the possibility of postwar peace.

Dropping the bomb would shatter any trust the world had in the United States' desires for truly lasting peace, which the scientists bluntly stated, saying, "This kind of introduction of atomic weapons to the world may easily destroy all our chances of success." They had effectively predicted all of the fears that would come with the Cold War.

As such, those scientists advocated for transparency and to display the bomb in a test setting to diplomats from all over the world. By demonstrating power rather than deploying it in secret, they argued that it may prove the U.S. was willing to work with other nations to prevent — rather than promote — nuclear warfare. A seemingly positive outcome, especially with the power of hindsight and knowing the arms race of the Cold War. But policymakers ultimately refused to consider anything aside from military usage of the bomb, overlooking the possibility of future peace.

Some studies claim that nuclear radiation might not have been bad

If there's one thing about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that almost everyone can agree on, it's that the radiation released by the bombs left thousands of people sick, killing many of them years after World War II ended. But some studies have claimed that low levels of radiation might actually prove beneficial, and they've used survivors from the outskirts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to argue their point.

The studies followed over 100,000 survivors, tracking their medical history over the decades, starting from 1950. More specifically, some of those survivors experienced relatively low levels of radiation — so low that they didn't actually experience radiation sickness. But the strange part of that was the conclusion drawn at the end of it all: Those who experienced such low levels of radiation didn't just avoid the negative effects of radiation. They also had comparatively low levels of mortality compared to people who weren't exposed to radiation at all.

As confusing as that sounds, the finding is technically supported by science, though even then, the entire situation is complicated. Pre-existing theories, particularly the hormetic theory of radiation, already existed that argued a similar point, saying that specific types of radiation, when experienced in low doses, can have health benefits. But larger organizations like the National Academy of Sciences and the United Nations don't recognize that theory at all, making this entire finding a little confusing to fully understand.

Nagasaki wasn't supposed to be bombed

In the present day, the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are almost always mentioned in the same breath, with both cities once destroyed by atomic bombs. But at the time, those two cities were not nearly as linked as they are today. A series of bizarre events and remarkably bad luck led to that.

In their initial plans, officials were explicitly looking for large cities (both in terms of size and population) of particular military value. They managed to put together a short list of four cities that met all their criteria: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Kyoto. In other words, Nagasaki wasn't a primary target for the atomic bomb and was not mentioned on the list at all. It seemed like the city would be saved from destruction. But in June, Secretary of War Henry Stimson suddenly changed the list for reasons still debated today. According to him, Kyoto was too important a cultural center to be destroyed, but some historians have argued that he wanted to spare the city for personal reasons, as he might have spent his honeymoon there. Nagasaki was bumped onto the list of four candidates, literally handwritten into the new draft, but still in the last spot.

Things only got worse from there. Cloudy weather in the days leading up to the planned second bombing forced plans to change, and at the very last minute, the planes couldn't get a clear visual over Kokura, pushing the pilots to make the switch to Nagasaki on the spot.

Kyoto wasn't targeted for sentimental reasons

As the plan to drop nuclear weapons on Japan took shape, American military planners drew up a list of Japanese cities to potentially target. Among them was Kyoto, which had seen less conventional bombing than many other Japanese cities, and so the destruction of an atomic weapon would be especially plain there. Kyoto had been the capital of Japan until the Meiji Restoration — "Kyoto" is Japanese for "capital city" — and it occupies a special cultural place for Japanese people due to its beauty, long history, and Buddhist heritage.

Luckily for Kyoto, the U.S. Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, had honeymooned there a number of years before the war and had enjoyed himself. He took Kyoto off the target list every time it was added and eventually took his case to President Truman. Stimson argued, reasonably but perhaps disingenuously, that the anger the Japanese people would feel at the destruction of beautiful, historic Kyoto would harden them against the future American occupation, perhaps causing them to place themselves within the Soviet sphere of influence. Stimson prevailed, and today over a third of Japan's population visits the city each year.

Kyoto's place on the list was taken, fatefully, by Nagasaki. Nagasaki had its own long heritage as a center of foreign trade during Japan's isolation and as a center of Japanese Christianity, but these were not enough to spare it.

Plants returned sooner than anyone thought

After the bomb was detonated over Hiroshima, what little scientific consensus existed around the new technology predicted that the earth at Ground Zero would be effectively dead, with nothing growing, much less thriving, in the affected area for some 70 years. In a small mercy, nature defied these gloomy predictions. Weeds appeared within a few months. Oleanders blossomed in the spring of 1946. Camphor trees produced new growth. They were joined by a number of other trees, notably ginkgos, which survived the blast and were later dubbed "survivor trees," whose seedlings have been distributed worldwide as gestures of goodwill.

Today, the oleander and the camphor tree are recognized symbols of Hiroshima and its rebirth. Gifts sent by other cities to help in the reconstruction included trees to replace those atomized in the attack, and today Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Park hosts thriving greenery, underscoring the ultimately hopeful message of the city's survival.

Survivors faced prejudice

"Hibakusha," a Japanese term meaning "bomb-affected people," are sorted under Japanese law into several categories depending on their proximity to the detonations, including people in utero at the time whose mothers were exposed to the bombs' effects. After some foot-dragging and persistent pressure from advocacy groups, Japan's government enacted two laws for the aid and support of hibakusha, which among other considerations allows all survivors a monthly stipend. Despite these measures, hibakusha faced discrimination from their countrymen, with other Japanese people sometimes refusing to hire or marry them. This stigma led some to conceal their pasts even from their future children. Sixty hibakusha who found themselves isolated later in life are now buried in a mass memorial in Tokyo.

Today, hibakusha advocacy groups continue to press for their rights as well as a world without nuclear weapons. One such group, Nihon Hidankyo, won the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize for its work. Another organization dedicated to collecting testimony from survivors, Hibakusha Stories, has expanded its mission to include supporting other people affected by radiation and the production and testing of atomic weapons, including those affected by the Fukushima Daiichi incident, "downwinders" exposed from nuclear testing, and those involved in nuclear weapons constructions and their families.

Nagasaki took less damage

Nagasaki is discussed less than Hiroshima, unfairly but for understandable reasons. Even in Japan, the news of the second atomic strike was overshadowed by the huge development of the official Soviet entry into the war against Japan and invasion of Manchuria the very morning of the strike. Secondly, though it seems perverse to call this "luck," the exact circumstances of the bombing of Nagasaki meant that the second and hopefully last city to be hit by a nuclear detonation was not as badly damaged as its predecessor, Hiroshima.

Given that Nagasaki was already a second-choice target after Kokura, the plan to hit it was not fully developed. The population of bowl-shaped Nagasaki was then mostly concentrated in two valleys cutting outward from the city's harbor, and cloud cover on the fatal day meant that visibility was even worse than that over barely-spared Kokura. Low on fuel and with a single gap in the clouds, the bombing team did what it could, dropping the weapon in one of the valleys some distance north of the city center. Even though the Nagasaki weapon was objectively more powerful than the one that had slammed Hiroshima, the shielding effect of the terrain and the suboptimal strike site blunted its effect.

Even blunted, the Nagasaki bomb was devastating. After much estimation and revision, the official estimate of dead in the Nagasaki attack, arrived at by comparing census records from 1945 and 1950, is north of 70,000, with a broadly similar number injured.

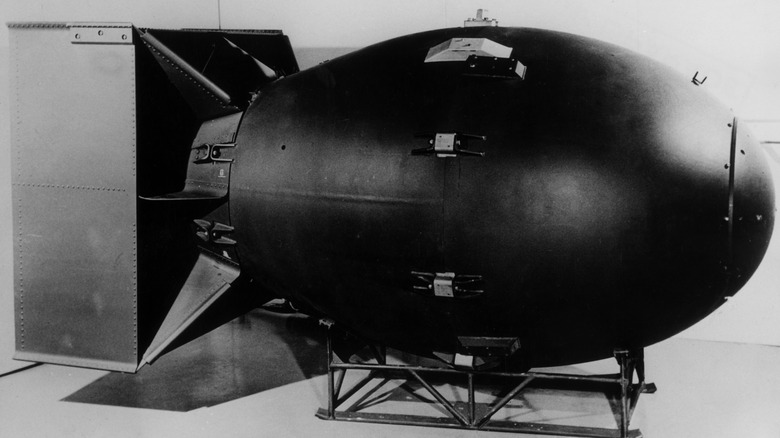

The Hiroshima bomb style had not been tested

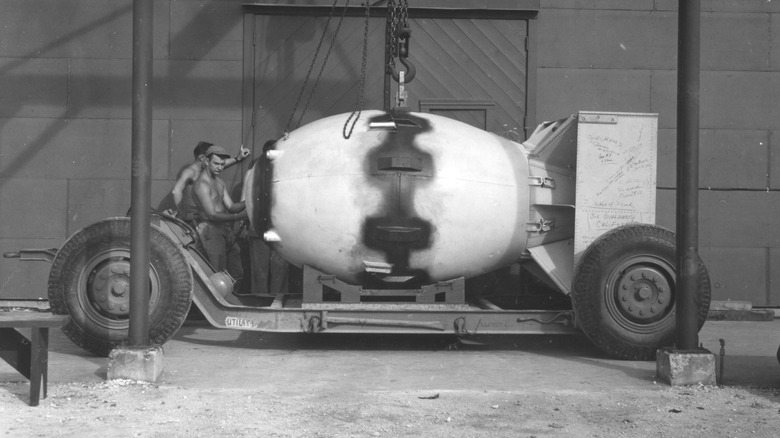

The bombs that struck Hiroshima and Nagasaki were similar in that they were both nuclear weapons, but they differed in key technical details. Both involved forcing a mass of unstable radioactive material to go "supercritical" and set off chain reactions of shattered atoms. Little Boy, destined for Hiroshima, featured two lumps of refined uranium shot at each other like paired bullets; Fat Man, which would hit Nagasaki, involved surrounding a plutonium core with a sphere of conventional explosives that would go off to compress and activate the plutonium.

The first plutonium bomb was successfully detonated at the (in)famous Trinity Test in July 1945, proving that the plutonium bomb concept worked. Uranium bombs were never tested before the strike on Hiroshima: Scientists were very, very confident that they would work, and the particular form of uranium required for a working weapon was hard enough to isolate that no one wanted to "waste" a bomb's-worth of it just to confirm what they already knew. After the real-world demonstrations in August, it was clear that plutonium weapons were more devastating and efficient, and most subsequent American nuclear weapons have followed the basic principles of Fat Man.

Even with the devastation plain, countries continued developing nukes

After Japan's surrender, the United States government sent one of the Manhattan Project physicists, Philip Morrison, to Hiroshima to survey the damage. The horrified scientist, confronted with the magnitude of the devastation, went on to campaign against nuclear weapons, insisting they were too horrific to use again. Unfortunately, he didn't sway Joseph Stalin. The wily Soviet dictator had correctly interpreted a casual comment by President Harry Truman as referring to U.S. nuclear weapons, and he leaned on Soviet scientists to hurry up production of their own bomb. This project was accelerated after the detonations in August 1945, and after overcoming some technical hurdles, the Soviets successfully tested their "First Lightning" weapon in 1949.

Activists worldwide have called attention to the nightmarish potential of nuclear weapons, framing them as morally unjustifiable money-sucks that threaten human civilization by both their immediate effects and the generational damage of fallout. Regional treaties ban the development or deployment of nuclear weapons across Latin America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific, but nonetheless, nine countries now have nuclear arsenals, with weapons deployed across a further six, totaling an estimated 12,000 bombs.

Their legacy gave us Godzilla

Japan is the only country to have been attacked with a nuclear weapon, and the national trauma of the bombs was compounded by an official code of silence under both the Japanese and American occupation governments. Japan, trying to keep a lid on the panic, squelched news of the bombs, and this policy was continued by the American administration until 1949. Today, even as Japan presents itself as a voice against nuclear proliferation, nuclear power is generated in Japan, and some sections of Japanese society are open to nuclear defense.

This complex relationship to nuclear options has, of course, emerged in Japanese popular culture, and Godzilla may be the loudest example. The iconic reptilian colossus, one of Japan's most recognizable cultural exports, was presented in the original Japanese film as having been awoken from its sleep under the ocean by H-bomb testing. The monster can be read as a clear warning of the dangers of nuclear weapons, reminding viewers that no one can really know what will be unleashed by careless use of such forces. And, of course, Godzilla ravages Tokyo, among other cities, time and again — an unexpected catharsis for a war-battered nation, but also a pattern that allows them to imagine other ways their history could have gone.

Godzilla isn't the only nuclear ghost in Japanese pop culture, either. Many other movies and manga reckoning with the attacks continue to be produced in Japan — perhaps they always will be.

It's impossible to count the dead

The truth death tolls of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are not and realistically cannot be known. Japan in the waning days of the war was already in disarray, with people fleeing conventional bombings in other cities. Some people had evacuated Hiroshima and Nagasaki before the attacks, but enslaved Koreans who did not necessarily appear in city records were assigned to work in certain facilities in each city. Commuters who worked in the city but lived outside it might have died but not been on resident lists.

The awesome power of the blast could completely destroy a human body at close range, and in the desperate days in the immediate aftermath, many bodies had to be hurriedly buried or cremated without being identified or tabulated, and even this process took weeks. Many other corpses were buried in rubble and found later. Additionally, the destruction obliterated a number of civic records in both cities.

An additional logistical challenge is deciding what deaths count as being caused by the bomb. October 1945 records in Nagasaki recorded 23,000 dead but acknowledged that this was surely an undercount due to the level of destruction, people having fled in the bomb's wake and thus being unaccounted for, and the slow progress of some deaths by radiation poisoning or other injuries received in the attacks. Later cancers added to death tolls, though probably in the very rough neighborhood of 3,000 more deaths. In both cities, credible estimates vary wifely, but with tens of thousands gone in each.

They began a change in human body chemistry

The Trinity Test and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the first of over 500 above-ground nuclear detonations that took place before treaties obliged further testing to move underground. Among the debris these tests spread across the world were previously unusual amounts of carbon-14, a radioactive form of carbon, which has since been incorporated into the tissues of every organism to live through or after the bombs' explosions.

Carbon-14 had previously been useful for scientists because it decayed slowly over time, and by measuring the amount of carbon-14 left in a given sample, they could estimate its age. This useful tool was formerly limited to older materials, as carbon-14 decays slowly enough that it needs time for the amount of decay to be detectable. The higher levels present now because of the tests have made carbon dating both more precise and applicable to "younger items," with scientists using it to help catch poachers and verify wine vintages. Levels of carbon-14 in the environment are now close to pre-bomb levels, but for those people, animals, and plants who took up the greater levels during their lives and development, the spike in carbon-14 will be detectable for the next 60,000 years.

The Genbaku Dome survived at nearly ground zero

Within Hiroshima Peace Park, which includes much of the area directly under the atomic blast, stands a uniquely Japanese oddity: the Genbaku Dome. ("Genbaku" is Japanese for "atomic bomb.") Before the blast, the structure was a municipal exhibition building called the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, designed by a European to look European and therefore "modern," complete with concrete and a dome on top. When the bomb went off nearly directly overhead, it killed everyone inside, but the straight-down shock wave damaged but did not destroy the building; the Genbaku Dome was the only surviving structure in its immediate vicinity.

After public debate, the striking, skeletal remains of the building were incorporated into Hiroshima's memorial to the bomb's victims. Conservation projects since 1945 have prioritized keeping the structure as intact and as close to its appearance after the attack as possible. In 1996, the dome was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the site hosts annual memorials each year on the anniversary of the bombing.

Whether the bombings were justified is still debated

Some 80 years after the bombings, historians, as well as the interested public, continue to discuss whether they were justified. The arguments are familiar by now. People justifying the bombs' use argue that pursuing the war by conventional means, ending with a planned invasion of the Japanese Home Islands, would have cost many American lives and no small number of Japanese dead, and that using the bombs ended a savage and monumental war once and for all. Those who disagree point to the enormous devastation the bombs wrought and their colossal death toll, especially given that most of the dead were noncombatants.

The debate has been complicated further by renewed attention to Japan's desperate situation in August 1945. One sticking point in negotiations was the American refusal to guarantee that the emperor could remain on his throne, but since Hirohito was ultimately allowed to remain (and reigned until 1989), this was not a quibble worth tens of thousands of lives. Additionally, the Soviet entry into the Pacific war and the Soviet army's rapid successes in Japan's mainland territories might have led to a quick surrender anyway. The debate remains, and attempting to answer it remains a common assignment for grade school classes — one such lesson plan is even provided by the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library.