WWII Details Too Horrific For History Class

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

When it comes time to look back at the biggest conflicts of the 20th century, it's safe to say that World War II is much more widely discussed than World War I. For as much as it's studied, though, it's impossible to cover everything in even the most in-depth history class. A class might teach the major events along the timeline of the war's European front, and there are likely some lessons given on the history of just how Hitler rose to power in Germany. Those are all incredibly important things that should not be forgotten — lest they be repeated — but there are some atrocities that are simply too horrific to be taught in most classes.

And that's saying a lot, because World War II is filled with stories that illustrate just how terrible people can be to each other. The old saying that war is hell is absolutely true, but the devil is definitely in the details. Those details shouldn't be overlooked, so we're going to talk about some pretty dark stuff.

Along the way, we'll get into what happened on the ground after the dropping of the atomic bombs, experimentation on human subjects, and why the Allied soldiers who liberated the concentration camps were convinced that everyone definitely knew what was going on yet chose to look the other way. We'll talk about civilian casualties, heroes who met fates that they didn't deserve, and horrors that need to be spoken of, as unspeakable as they may be.

A Japanese organization conducted vivisections on conscious prisoners

Perhaps less well-known than Nazi concentration camps are the atrocities committed by Japan's Unit 731, and it's dire stuff that includes grisly experiments on human prisoners of war referred to as "logs." It's unclear just how many of these experiments were done, but we do know that among the horrors was the complete vivisection and removal of organs of people who were fully conscious. In some cases, arms and legs were amputated, then reattached to other parts of the body, while female prisoners were raped, infected with venereal diseases, impregnated, and then vivisected.

In 2015, Toshio Tono spoke with The Guardian. He considered raising awareness of Unit 731 his life's work, and he was there — it was his job to clean up the blood following experiments on prisoners. Experiments he witnessed included the removal of organs, then keeping victims alive to see what happened. Tono said, "The experiments had absolutely no medical merit. They were being used to inflict as cruel a death as possible on the prisoners."

Most of the crimes committed under the Unit 731 umbrella were never punished or publicized, and post-war, most of the doctors involved went back to their practices and hospitals. Some have come forward. In 2006, 84-year-old Akira Makino gave an interview and described performing operations and amputations on sedated prisoners, as well as injecting prisoners with diseases like cholera. Evidence was largely destroyed in the last days of the war.

Grisly experiments on prisoners gave us information on frostbite still used today

There's a lot that can be written about the experiments of Japan's Unit 731, and none of it's easy reading. Since a lot of information and evidence were destroyed, it's unclear just how many people were subjected to experimentation, but estimates suggest the number might be as high as 12,000.

In addition to vivisection, forced infection with venereal disease, and starvation, a physiologist named Yoshimura Hisato conducted a series of experiments in which victims were restrained, had arms and legs frozen solid, and then thawed. The experiments — among others — are memorialized at the Unit 731 Museum in Harbin, China (pictured), and it's a difficult place to tour.

As shocking as the experiments are, it's perhaps even more shocking that the frostbite experiments in particular led to medical advancements still in use. Today, the go-to treatment for frostbite is soaking the area in warm but not hot water, and it was the experiments of Unit 731 that pinpointed the perfect temperature for treating frostbite at between 100 and 122 degrees Fahrenheit. That — along with the countless experiments performed by Nazi doctors — has led to major ethical debates over whether or not data gained by the Axis powers should be used.

Witnesses to liberation say locals had to know what was happening for 1 reason

There have always been questions raised about just how much ordinary German citizens knew about what was going on in Nazi concentration camps. In an interview with The National WWII Museum, 45th Evacuation Hospital veteran Andrew Kiniry said that he and the others who were at the liberation of Buchenwald (pictured) didn't believe claims of ignorance for one reason: The smell.

He isn't the only one. Many veterans have spoken of the smell of death that hung in the air around the camps and how it was often the first sign of a camp. In an interview with TVP World, Auschwitz survivor Leon Weintraub described what he remembered, decades later: "Suffering. Hunger. Cold. But first of all, the terrible smell of the smoke. The smell of burned flesh around the clock."

Alan Moskin was with the 66th Infantry, 71st Division when they discovered the camp Gunskirchen, telling Time that they had no idea concentration camps existed. The smell came first, and the corpses and the crematoriums were just part of it. Moskin recalled an elderly survivor: "I picked him up... and as he came up towards me I could see open, festering sores going up and down his neck, and lice coming out of those sores. ... he smelled so badly ... he wrapped his arms around me and he was crying. He kept saying, 'Danke, danke, Jew.' That's when I lost it a little bit and started to cry."

Millions of horses, mules, and donkeys died in awful ways

It's often overlooked that horses, mules, and donkeys played a huge role in the war, with between 3 million and 6 million horses used. Cavalry charges were rare, and instead, they were mostly tasked with transport. World War II exists in that weird space where technology and things like tanks and artillery were prominent, but unreliable. A better way to haul heavy machinery — especially over European roads and fields — was with horsepower.

As for deaths, estimates vary. Some historians put the number of horse deaths at 3.5 million, and that comes with some awful facts. After countless war horses were abandoned after World War I, British authorities promised owners that if their horse was drafted into the war effort and survived, it would be returned ... or executed.

There are also some heartbreaking tales told by those who were at the liberation of some of the concentration camps. Alan Moskin was 18 years old when he was at the liberation of the Gunskirchen Concentration Camp, and in an interview with Time, he recalled a grisly scene where three starving prisoners came upon a dead horse: "[They] had pulled off the bark of a tree and were digging it into the entrails of this dead hose. And then they reached down inside the dead horse, and pulled out the guts and started biting and chewing. You could see the blood squirt out."

A Nazi euthanasia program kicked off with the killing of a 5-month-old boy

The Nazi Final Solution targeted multiple groups of people, and by the end of the war, around 300,000 disabled people had been killed. It all started with Adolf Hitler's long-standing belief that the disabled should be euthanized, and parents who wanted to do precisely that to their disabled son.

For a long time, he was known only as "Case K," with his real name finally released in the early 2000s. The details of Gerhard Kretschmar's birth vary, but it's generally accepted that he was born at least partially blind and without one or more limbs. His parents called him "The Monster," and they asked their doctor to kill him. Hitler gave the go-ahead, and on July 25, 1939, the 5-month-old was administered a lethal injection. He became the first of many, including children who were removed from their parents after being reported for selection by doctors. In some cases, parents were told their child would be sent to an institution, and later received death certificates citing illnesses.

The idea goes back to the 1920s, and Dr. Ewald Meltzer. He provided the groundwork for Aktion T4, as when he was the head of a facility in Saxony, he tried to prove his patients' worth to their families. He reported that 73% of parent respondents were in favor of a program that would allow for the killing of their children, with many approving if they didn't have to know about it.

FDR was gifted a letter opener made from Japanese bones

There are a few different accounts of what, exactly, President Franklin D. Roosevelt's response was when he was presented with the arm bone of a Japanese soldier. The bone had been turned into a letter opener, and the gift-giver was Pennsylvania's Representative Francis E. Walter. In one account, FDR lit a cigarette, and in another, he reportedly said (via Reuters), "This is the sort of gift I like to get." FDR ultimately returned the bone, but it was definitely not the only time remains — particularly of Japanese soldiers — were sent to the U.S. as souvenirs.

The practice was so widespread that Charles Lindbergh wrote that he was asked to declare human bones to customs. It was so bizarrely ordinary that in 1944, Life ran a picture of a woman writing a thank-you note to her boyfriend who was stationed in the Pacific theatre for sending her a Japanese skull he and his friends had signed.

Other photos show skulls being mounted on ships and treated as mascots, and many condemned the practice — which involved prepping skulls by skinning, washing, and bleaching them. However, that boyfriend who sent the skull that was featured in Life was reprimanded only because the photo was circulated in Japan as an illustration of just how horrible American troops were. One newspaper wrote (via Lapham's Quarterly), "Even on the face of the American girl can be discerned the beastly nature of the Americans."

Around 40,000 dogs were sacrificed in a Soviet attempt to weaponize them

Dogs have long been prized for their loyalty, so it's not surprising that they've always had a place in war. Starting in the 1930s, the Soviet military began experimenting with a dog-delivered bomb. The idea was initially that they'd carry the bomb on a harness, drop it at the designated spot, then return, but when that proved too complicated to be practical, there was a change in plans.

And yes, it's going precisely where you think it's going. Bombs were strapped onto the dogs, which were trained to run under tanks — in theory — by starving them, then only giving them food under tanks. The hope was that they could be released on the battlefield, and detonators would be used to destroy dog and tank alike.

Did they put this plan into action? Also, yes, starting in 1941. The Soviets trained somewhere around 40,000 dogs, and since the Axis knew exactly what they were doing, they often just targeted and shot the dogs before they got anywhere near German tanks or troops. The dogs also had a tendency not to want to go into the middle of battle, and since their training was done with Soviet tanks, many just headed for those instead. And that? That's kind of called karma.

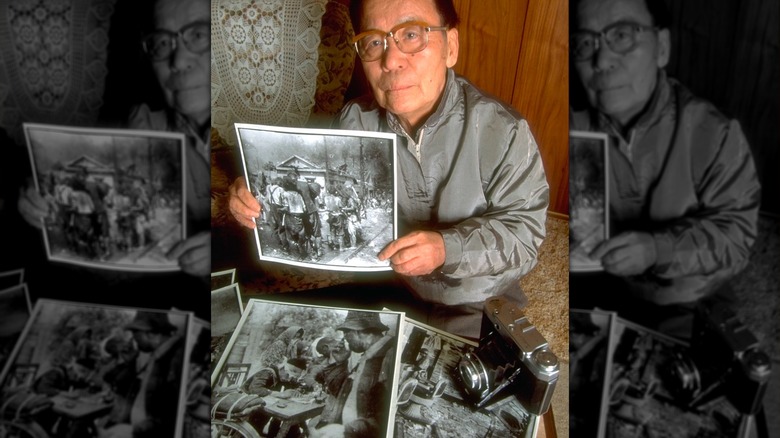

Only 5 photos are left to document the immediate aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima

There are a ton of photos of completely destroyed cities in the days, weeks, and months after the bombing, but there are only five of the immediate aftermath. They were taken by Yoshito Matsushige, a photographer who was 352 yards outside of the ground zero perimeter. In an interview with the Atomic Heritage Foundation, he wrote of some scenes so terrible that he couldn't take a photo: "I felt so sorry for these dead and naked people whose photo would be left to posterity that I couldn't take the shot."

In the end, he ended up with just five photos, with many of the people in them later being identified. The photos include the inside of a barber shop, a police officer sitting at a table and surrounded by the wounded, and a shot looking out of a broken window.

The two other photos were taken first, and most of the people in the photos are girls from two nearby junior high schools. He wrote: "Having been directly exposed to the heat rays, they were covered in blisters, the size of balls, on their backs, their faces, their shoulders and their arms. The blisters were starting to burst open and their skin hung down like rugs. Some of the children even have burns on the soles of their feet. They'd lost their shoes and run barefoot through the burning fire."

The Soviets executed Poland's greatest resistance fighter as a traitor to Communism

The thing about World War II is that even though there were unthinkable atrocities, there were also stories of ordinary people who did extraordinary things in order to stand up to the Nazi regime. That includes Witold Pilecki, a Polish farmer who joined the resistance and then volunteered to go to Auschwitz.

Pilecki spent a full two and a half years there, essentially organizing prisoners into resistance groups and smuggling out information that was ultimately passed on to Allied leaders. He described everything in painstaking detail, reporting on things like the medical experiments, the gas chambers, and how many people came and went through the camp.

Writing about his first day there, he noted (via NPR), "I got a blow in my jaw with a heavy rod. I spat out my two teeth. Bleeding began. From that moment we became mere numbers — I wore the number 4859." He contracted pneumonia and typhus, and when he finally did escape, it was with a week-long, more than 60-mile march. He was one of 144 people who escaped.

That's pretty incredible, so where does it take a horrific turn? Pilecki survived the war and ultimately returned to Soviet-occupied Poland. He was arrested, accused of being a spy, tortured, and on May 25, 1948, he was executed. His name was removed from most public records until the 1990s and the fall of Communist Poland.

Prisoner-doctors were forced to perform horrible experiments on other prisoners at Auschwitz

There are a lot of incredibly brave and sadly often-overlooked women who made outstanding contributions during World War II. We want to talk about Dr. Dorota Lorska right now. Lorska had to leave Poland and move to Czechoslovakia to find a school that would accept a female and Jewish medical student, and she would ultimately end up in France as a part of the resistance. When she was arrested and sent to Auschwitz, she was assigned to the notorious Block 10... as a doctor.

For anyone not familiar with Block 10, that was the block where Nazi doctors performed a series of experiments largely dedicated to the use of radiation to forcibly sterilize both men and women. Lorska was there for about a year, and would later write (via Medical Review Auschwitz), "That nightmare impression from my first days spent there — a mix of hell and a madhouse — is still haunting me now. It keeps resurfacing whenever I think of those times, and keeps coming back in my dreams — reminding me of that grim and bizarre reality."

After joining Auschwitz's internal resistance, Lorska wrote detailed reports on the experiments, which made it to London and provided an invaluable account of what was being done. She wrote that prisoner doctors were made to not only assist in experiments, but were sometimes forced to perform them in their entirety. Lorska survived the camps and died in 1965.

The media drove popular opinion stateside, and led to Japanese-American internment camps

The truth about America's World War II-era internment camps makes for difficult reading. Around 120,000 people — many of whom were American-born — were forced from their homes and sent to live in internment camps. (Among the most famous is George Takei, who has written several books about the experience, including "They Called Us Enemy," and "My Lost Freedom.")

According to Digital History, officially, seven people were shot and killed, 1,862 died there of other causes, and 1,322 are listed as having been institutionalized. The reasoning behind the camps was twofold, and was said to have been done because of fears of Japanese spies in the Japanese-American population, as well as fears over the potential for violence. Most of those fears were public ones, not military ones, and have been traced back to the promotion of racist ideas by the mainstream media, specifically, William Randolph Hearst's newspapers.

By the time war broke out, Hearst papers were also notoriously anti-immigration and promoters of the so-called "Yellow Peril," running stories and cartoons that promoted a pretty nasty picture of the Japanese. After Pearl Harbor, many Americans were already predisposed toward racist ideas. Take this excerpt from The San Francisco Examiner, published on January 29, 1942 (via PBS): "Herd 'em up, pack 'em off and give 'em the inside room in the badlands. Let 'em be pinched, hurt, hungry, and dead up against it. ... Let's quit worrying about hurting the enemy's feelings and start doing it."

The British stole the corpse of a Welsh homeless man

Operation Mincemeat was a brilliant bait-and-switch that allowed the Allies to successfully invade Sicily. The plan is generally credited to none other than James Bond's creator and author, Ian Fleming (pictured), and the idea was to take a dead man, plant official-looking yet absolutely false information on him, then drop him somewhere where he'd be picked up by Spain. Spain would pass the bad intel on to Germany.

It worked. Nazi troops were moved from Italy to Greece, and when the Allies attacked Italy, they were up against a fraction of the firepower. Where this gets sketchy is how the Brits got the dead body: They kind of stole it.

The body was that of a Welsh man named Glyndwr Michael, and he had (officially, at least) died by suicide in 1943. His body was recovered from a London warehouse, then taken by a coroner who had been contacted by the government and told to keep an eye out for a suitable corpse. The operation was carried out by agents who had essentially gone rogue to get it done, claiming they had definitely, absolutely, positively gotten approval to use the body. Ben Macintyre is the author of "Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured and Allied Victory." He explained to the Los Angeles Times: "They believed he had no family. They were wrong about that. They just thought they could get away with stealing the body."

The so-called comfort women forced into sexual slavery by Japan's military

In 2020, NPR interviewed 89-year-old Narcisa Claveria. She was one of the thousands of women sentenced to live in camps — usually established alongside military garrisons — to serve as so-called comfort women for the Japanese Army. She said: "If I could prevent the sun from setting, I would, because whenever night fell, they would start raping us." For Claveria, those are the memories of what it was like to be a 12-year-old girl.

Women and girls were often taken from poor families, and although many were from Korea and China, they came from all Japanese-occupied territories and into a system officially overseen by the government. From 1932 to 1945, hundreds of thousands of women were passed through the system officially established with the goal of boosting morale and ironically, preventing rape. According to the accounts of survivors, they would be assaulted by anywhere from four to 60 men every day. Those who refused or tried to escape were tortured, beaten, or killed.

By 2019, there were only about 20 known survivors from South Korea, and advocates were making it known that they had a very limited amount of time to get a formal apology from Japan. Advocates are also pushing awareness, and books like "The Comfort Women: Japan's Brutal Regime of Enforced Prostitution in the Second World War" by George Hicks, or "Chinese Comfort Women: Testimonies from Imperial Japan's Sex Slaves" from the Oxford Oral History Series.

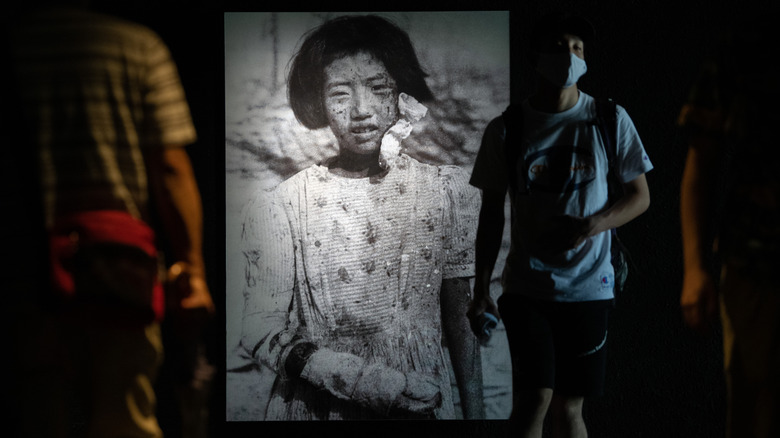

Stories from the civilian survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were rarely told in the US

Back in 2015, The Washington Post headed to Reddit to try to find out if there was a difference in the way the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings were taught around the world. It wasn't until the end of the 2000s that American students were starting to see textbooks that gave the perspectives of civilian Japanese survivors, and it's pretty terrifying stuff.

Time has published a series of accounts. One survivor was 6 years old, and her mother — on a hunch — had kept her and her sister home from school. That school was in the blast zone, and everyone was killed. Another recalled being trapped in a bomb shelter for three days as victims joined them: "Their skin had peeled off their bodies and faces and hung limply down on the ground, in ribbons. ... Many of the victims collapsed as soon as they reached the bomb shelter entrance, forming a pile of contorted bodies. The stench and heat were unbearable."

Another man attempted to cremate his father, but when he returned the following day, it was to a partially burned body. One woman was 8, and never saw her 12-year-old sister again, and never knew what happened to her. Another remembered being at work when the bomb hit, and seeing a coworker. "His skin was melted off, exposing his raw flesh. ... 'Do I look alright?' he asked me. I didn't have the heart to answer."

Cannibalism was not unheard of

One downed plane became famous when a survivor became America's 41st President. The military career of President George H.W. Bush included being shot down over Chichi Jima, and eight of his fellow crewmembers were tortured, beheaded, and cannibalized by Japanese officers. (For an account of the incident, check out James Bradley's "Flyboys: A True Story of Courage.") That's far from the only report of cannibalism.

Allied troops liberating the concentration camps also found signs of cannibalism: A 1945 report of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen estimated that 30,000 people had died of starvation in the previous months. The Guardian reported that one medic said, "The prison doctors tell me that cannibalism is going on. There was no flesh on the bodies; the liver, kidneys, and heart were knifed out." Mentions of cannibalism were in reports of other camps, too, although the extent is difficult to gauge because of survivors' reluctance to talk about it. In one interview with a survivor from Mauthausen (pictured), a man identified as Moses S. recalled starving prisoners scrambling to eat the bodies of those who had been killed in a bombing (via HMC).

Cannibalism has been well-documented in books like "Cannibalism Culture: The Bushido Horror of World War II," which includes stories of Japanese soldiers prepping flesh from POWs who were still alive. Historian Toshiyuki Tanaka has found documents that refer to more than 100 incidents of cannibalism, saying that in some cases, the flesh of Allied troops was eaten at victory celebrations.

After the bombs came the black rain

An estimated 200,000 people were killed by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, and survivor stories are horrifying. Death tolls are estimates because many bodies in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki were simply vaporized, and survivors have spoken about how the bombs were just the start of the horrors. In the hours immediately afterwards, the city was covered with a black rain.

It happened in part because of that distinctive mushroom-shaped cloud, which created a pocket of cooling air, heat from the fireball, dust, debris, ash, soot, and — if we're being honest — probably human remains. (And calling it heat is kind of an understatement. The temperature at ground zero was somewhere around 7232 Fahrenheit.) The air cooled and rain formed, but carried on that rain was the remains of the city and radioactivity.

That black rain was described as being more like a sticky, black tar than water, and in one survivor testimony, Akiko Takakura described it (via the Smithsonian): "It was just like a living hell. After a while, it began to rain. The fire and the smoke made us so thirsty and there was nothing to drink... People opened their mouths and turned their faces toward the sky [to] try to drink the rain ... It was a black rain with big drops." Shockingly, it wasn't until 2020 that some black rain survivors were granted bomb survivor status and the right to medical benefits.

Thousands — including civilians — died by suicide at Saipan's cliffs

In a weeks-long battle that ended on July 9, 1944, U.S. forces set up on the island of Saipan. The island was of particular strategic importance as it was within a B-29 bomber's range of Japan, and there's an incredibly tragic footnote to this. By the end of the fighting, 22,000 civilians were dead, with many choosing to die by suicide along two cliffs, known as Banzai Cliff and Suicide Cliff (pictured).

Entire families jumped to their deaths, with witnesses reporting that parents and young adults killed their children and elderly relatives before jumping. Ota Masahide explained (via the Atomic Heritage Foundation), "As the mayhem unfolded, they found all sorts of ways to kill ... What they had in common was the belief that they were doing this out of love and compassion." It was believed that death was preferable to surrender to American forces, and there are truly awful stories that include the one told by Koyu Shiroma.

He was 5 years old when he and his father headed to the cliffs. Shiroma told PBS, "... my father usually tell me, you know. American people will kill you ... so I just follow people, people, and a lot of people jump the cliff. So everybody jumping, so I just jump myself." He did, but was saved by American forces after he was caught on a tree branch on the way down. He never learned what happened to his two younger sisters.

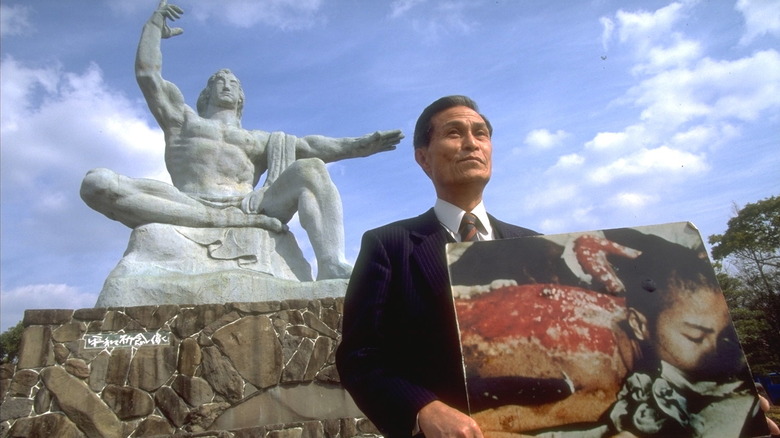

Post-atomic bomb footage was suppressed for decades

There have been a lot of thought experiments done to try to figure out what the world might look like if the atomic bomb had never been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the very unsettling footnote to that is that for years, the world didn't know anything about what had really happened there. Film footage and photographs taken by multiple militaries were completely suppressed, and military experts have testified that it was kept secret simply because it was too horrible for people to see.

It's easy to understand how the release of the film may have changed the world's view on nuclear weapons, especially if you know the story of Sumiteru Taniguchi (pictured), activist and author of "The Atomic Bomb on My Back." He was 16 years old when the bomb dropped, and his wounds were so severe that he was in the hospital for the next three years and seven months. His treatment was photographed by a Marine, who refused to surrender the images and instead hid them. They were eventually published.

Taniguchi has described his injuries (via PBS): "My wounds started to rot and run. My living body was burnt, but only after a month did it start to rot." He spent so much time in bed that he developed sores that exposed his organs, and he couldn't get proper medical treatment for 15 years and remained a vocal proponent of peace until his death in 2017. He was 88.

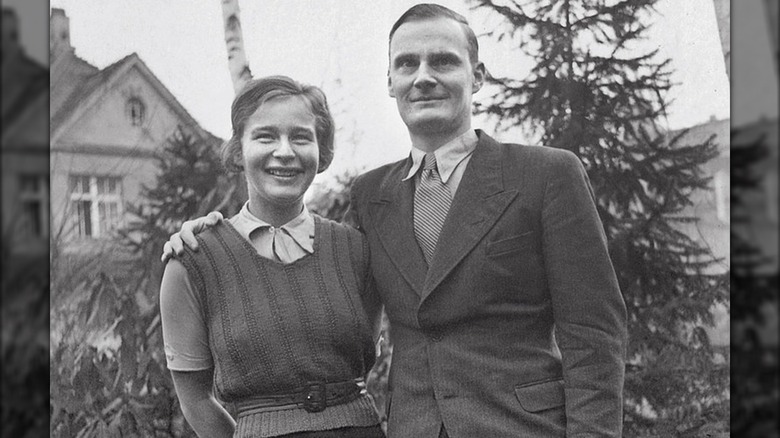

The med student who realized she knew the research corpses

It was a very, very strange series of events that led to a huge 2012 controversy in the U.S., and it kicked off when some members of Congress claimed that if a woman is sexually assaulted, it almost never results in pregnancy. That claim was actually a reference to work done by Nazi scientists, particularly, one of the most prominent anatomists of the era. That was the University of Berlin's Hermann Stieve, and he — along with other anatomists — sourced cadavers for all kinds of experimentation from among those executed by the Nazis.

One of the students who recorded this was Charlotte Pommer, who was told that med students were dissecting the cadavers of criminals. She was in Stieve's anatomy classes when she was tasked with observing one dissection, and when she saw the bodies, she found herself face-to-face with people she knew: Harro and Libertas Schulze-Boysen (pictured). They had been executed for speaking out against the Nazi Party.

They weren't the only ones, either. Around 300 resistance fighters have been identified as being sent to Stieve alone, and remains were still being found and properly buried in 2019. Most of his preferred corpses were female. Women were monitored while they were held in prison, and when they were executed, Stieve dissected them to try to find out what impact stress had on the reproductive system. His findings eventually led to the disproven claim repeated in 2012 that women who are assaulted won't get pregnant.