Former Staffers Who Had A Lot To Say About These Presidents

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

It has been more than two centuries since George Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States. As commander-in-chief of the armed forces and, from the 20th century, the person regarded as the leader of the free world, the U.S. president can wield considerable influence abroad. At home, their ambitions are checked and balanced by the legislative and judicial branches of government.

Many holders of this prestigious office have come and gone with barely a ripple, while others are inextricably linked with some of the country's most historic events. During these momentous tenures, they were both praised and condemned for their actions from all quarters — including their closest aides in the White House.

Although being president of the United States is a job for one person, thanks to the men who wrote the Constitution, their work isn't carried out alone, and staffers have had plenty to say about their bosses. Here are their thoughts on some of America's most consequential presidents, offered during and after their time in office.

Donald Trump

On January 20, 2017, businessman Donald J. Trump became the 45th president of the United States. In his inaugural address, he vowed to put "America first," having adopted Ronald Reagan's "Make America Great Again" (MAGA) motto. In his first term, Trump signed legislation securing a historic 40% cut in corporate taxes, appointed three Supreme Court justices, and slashed government regulation.

But these successes were overshadowed by many lows as he ripped up the rule book. They included his administration's controversial response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Trump's unorthodox approach to intelligence briefings, his thousands of false statements, and his umpteen outrageous comments. For MAGA supporters, Trump's presidency was what Washington, D.C., needed: unpredictable and tough. To many insiders, it was a horror show. Chief of staff General John Kelly, appointed in 2017, tried to impose order on a chaotic White House but was gone by December 2018. He subsequently became one of Trump's most scathing critics.

In 2023, Kelly confirmed to CNN that Trump had disparaged U.S. soldiers, and described him as a fan of dictators and autocrats, adding, "God help us." A year later, shortly before Trump's second successful presidential campaign, Kelly told The New York Times, "He certainly falls into the general definition of fascist." Several former White House officials signed a letter, sent to Politico and supporting his comments, that said, "Everyone should heed General Kelly's warning."

Joe Biden

When Joe Biden abruptly stepped back from taking a second shot at the presidency in the summer of 2024, many people, including political leaders, breathed a sigh of relief. His disastrous performance in the June debate against Donald Trump horrified Democrats and sounded alarm bells among even ardent Biden supporters. For a man who had dedicated more than 50 years to public service, it was an ignominious, tragic outcome for Biden — but it wasn't a total surprise to staffers.

Weeks after Trump was sworn in as the 47th president, Michael LaRosa, Jill Biden's former press secretary, revealed that Biden's team were well aware of the former president's apparent decline. Talking to Tara Palmeri in February 2025, LaRosa denied there was a cover-up about Biden's health, as claimed in Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson's book "Original Sin," but acknowledged that everyone knew "from day one" that age was going to be a potential problem for Biden.

However, LaRosa also assumed the president would "pass the torch to another generation of Democrats." He told Palmeri, "Deciding to run for re-election again was a misread of our mandate." In a later interview for The Young Turks, LaRosa said the administration had bullied reporters and was "hostile and very suspicious of all journalism, all journalists."

Barack Obama

Barack Obama will forever be known as the first African American to be elected president of the United States. His biggest policy achievement came in his first term when the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) was passed. Yet the flagship policy was hamstrung not just by bitter Republican opposition, but a botched roll-out. "This was one of the unhappiest times I've spent in government," William B. Schultz, former general counsel of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said in a speech at Harvard Law School.

Obama's reluctance to fire someone over the debacle also frustrated some staffers. The president's former press secretary Robert Gibbs told The New York Times that a message needed to be sent that "failure on this scale is simply unacceptable." It wasn't the only source of irritation. Foreign policy was a major bugbear too. In 2014, Obama's ex-defense secretary, Leon Panetta, published "Worthy Fights," detailing his time with the president who, despite his image, had his fair share of questionable moments.

In the book, Panetta cited Obama's "frustrating reticence to engage his opponents" and claimed he "avoids the battle, complains, and misses opportunities," per USA Today. In his memoir "Duty," ex-defence secretary Robert M. Gates claimed the president was "skeptical" about his own peace plan for Afghanistan. Even out of office, Obama has faced criticism. In 2024, hundreds of former staffers urged him to persuade the Biden administration to broker a Gaza cease-fire deal.

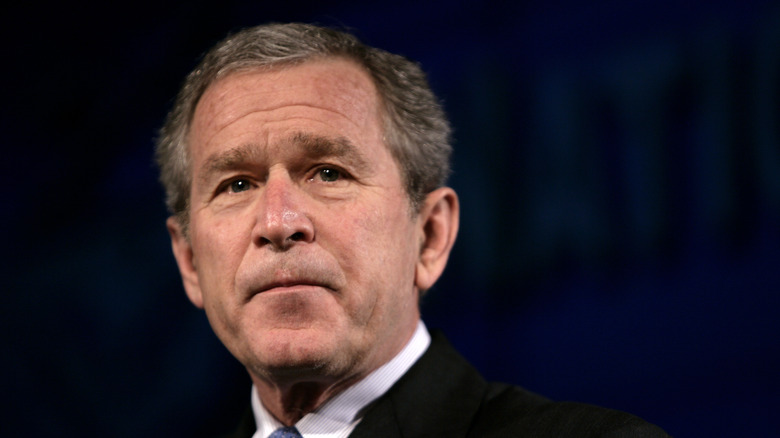

George W. Bush

Inaugurated as president in 2001, George W. Bush saw his biggest test in September that year with the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon. His response was to launch the "war on terror" followed by the invasion of Afghanistan and then Iraq two years later. While some speculated the hawkish foreign policy was driven by Vice President Dick Cheney, White House Chief of Staff Joshua B. Bolten and national security adviser Stephen J. Hadley dismissed that theory as "bunk" and "hooey," respectively, in a 2009 interview for NBC News.

Yet three years earlier, speaking on "Frontline," Richard Clarke, a former member of the White House National Security Council, suggested just that. He criticized the Bush administration for allowing Osama bin Laden to escape, and claimed all the president wanted was a connection to Iraq's Saddam Hussein to be found.

Clarke wasn't the only former staffer who had much to say about President Bush's handling of the Iraq invasion. In his 2008 book "What Happened," ex-aide and press secretary Scott McClellan dubbed the war a "serious strategic blunder," claiming Bush and his team were more focused on re-election than the best interests of America. Paul O'Neill, former treasury secretary and major contributor to "The Price of Loyalty" by Ron Suskind, went further. He said during cabinet meetings with Bush, he felt the president was "like a blind man in a roomful of deaf people."

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton served as United States president from 1993 to 2001. He ended the ban on gay people serving in the military, presided over a time of economic growth, and enacted major legislation such as the Family and Medical Leave Act. But Clinton also failed to pass health insurance legislation, faced scrutiny over his business dealings in the Whitewater scandal (one of several to involve Clinton), and lost both the House and Senate in the 1994 midterms.

Yet his popularity was undimmed. In a 2007 interview for Vanity Fair, Jack Valenti, a former aide to President Lyndon B. Johnson, said Clinton was the "best political strategist," while ex-chief of staff John Podesta told Frontline, "One of the things that I greatly admire about him is the guy never gives up." Not everyone thought of Clinton so fondly. Roger B. Porter, George H.W. Bush's economic and domestic policy adviser, denied that a conversation between him and Clinton, which Clinton claimed in his book "My Life" prompted him to run for office, ever took place.

Ex-staffer Linda Tripp, who blew the whistle on Clinton's relationship with Monica Lewinsky, claimed White House "housekeeping staff was afraid to bend over in his presence," according to The Weekly Standard (per Newsweek). In "The Breach," Peter Baker wrote that HHS Secretary Donna Shalala told the president: "I can't believe that is what you're telling us, that is what you believe, that you don't have an obligation to provide moral leadership."

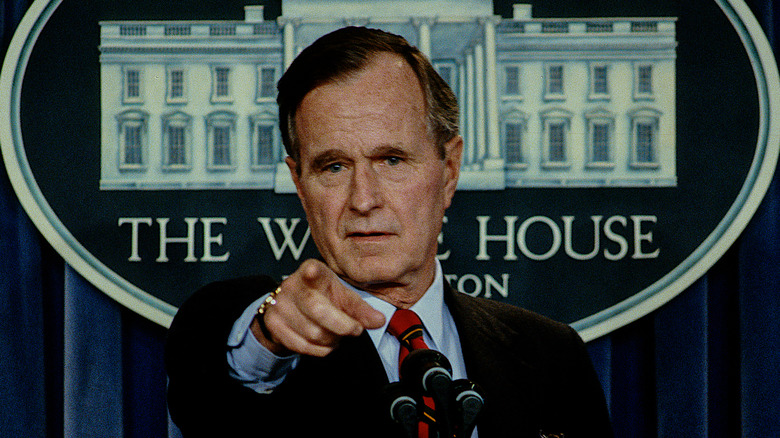

George H.W. Bush

A two-term vice president under Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush was elected to the White House in 1989, where he gained a reputation for focusing more on international rather than domestic affairs. In a 1991 edition of "Meet the Press," senior adviser Roger B. Porter rebuffed the question of whether the president was "paying sufficient attention to activity at home" (per Los Angeles Times). Bush's popularity was bolstered by successes abroad, including the effective end of the Cold War and a victory over Iraq after the invasion of Kuwait, where multiple assassination plots against him were planned.

Many former staffers paid tribute to Bush after his death in 2018. James Baker, former secretary of state, described the president as a "gentleman" who had a "steely resolve." He told PBS Newshour: "When he decided he wanted to do something or was going to do something, there wasn't any swerving." Jean Becker, Bush's former chief of staff, remembered his sense of humor as well as his "servant's heart" in an interview with KPRC 2 Click2Houston, and in 2023, told Presidential Leadership Scholars he was a good listener, with no ego. "President Bush was just really good at getting people," she said.

Former press secretary Peter Roussel recounted to PBS how he experienced Bush's "calmness and excellent judgement" under pressure first hand, while Colin Powell, who was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Bush, told NPR: "He was the most qualified president to take over that office in our history."

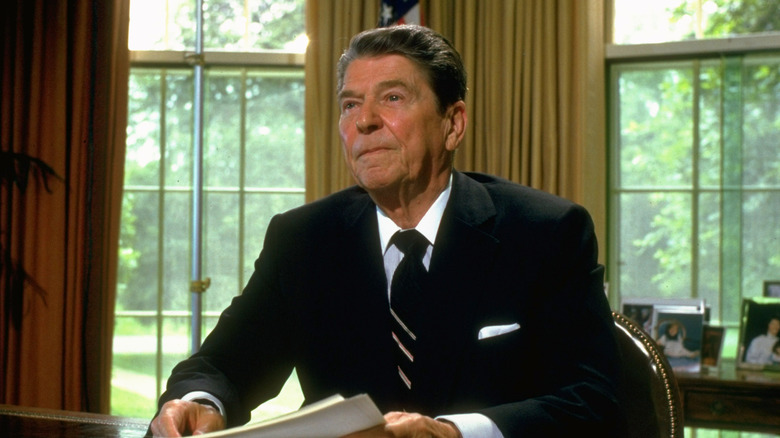

Ronald Reagan

Former Hollywood star Ronald Reagan cut his teeth in politics as president of the Screen Actors Guild and was elected as governor of California twice, before securing the White House in 1981. A staunch conservative, he was an advocate of "peace through strength" but faced scandal in the mid 1980s with the arms-for-hostages deal known as the Iran-Contra affair.

In 1987, Kenneth Duberstein was drafted in as chief of staff to help rehabilitate Reagan's image after the scandal, when, as he explained in a 2004 "Ask the White House" session, "many people thought of [Reagan] as a 'dead duck.'" An article for The Chief of Staff Association quoted him as saying of the president, "he understood the issues far more fervently if you, in fact, had people discussing in front of him."

Reagan angered Arthur Schlesinger Jr., a former special assistant to President John F. Kennedy, by suggesting that FDR's New Deal was based on Italian fascist policies, dubbing it a "gross distortion of history," according to Time. But he was remembered with affection by his former executive assistant Peggy Grande, who described him as a "man of faith, integrity, character" and said he was a "great communicator" (via The Daily Mississippian). Former staffer James Baker described him at an anniversary event in 2018 as "principled" and "pragmatic" and said that, despite his conservative image, "he was quite willing to reach across the aisle to get things done."

Jimmy Carter

Time has been kind to President Jimmy Carter. His tenure, which ran from 1977 to 1981, was regarded by many as a failure. In retrospect, his progressive vision on energy and equality, as well as his foreign policy successes, are viewed more favorably today. Former special assistant Peter G. Bourne, writing in The Guardian, said Carter did more in his single term "than most presidents accomplish in twice the time."

That perhaps doesn't include the 15 cabinet-level and 18 members of senior White House staff who tendered their resignations in July 1979. One staffer told The New York Times: "We thought it would give the President a free hand in making the decisions he has to make." Carter's former treasury secretary Michael Blumenthal was more blunt. In his book "From Exile to Washington," he wrote that Carter's was a "problematic presidency," and that Carter had effectively fired him.

Out of office, people learned there was more to Carter than met the eye, but those who worked with him in the White House had fond memories. Barry Jagoda, a former television adviser, described Carter as a "truth-teller and compassionate leader," telling 10 News that Carter had "restored a sense of dignity to the United States and around the world." Former staffer Fran Ryan told WOSU 87.9 NPR News that Carter was "honest" and "caring" as well as hardworking. "He was very real," she said.

Gerald Ford

Former sports star-turned-politician Gerald Ford became the 38th president of the United States after the resignation of Richard Nixon, but his time in the White House was dominated by his predecessor. Within weeks of taking office, Ford pardoned Nixon, a move that was ill-received by staff, politicians, and the country. He also grappled with serious economic and social issues amid criticism from both sides of the aisle.

Alexander Haig was chief of staff to both Nixon and Ford. "People will never know what a courageous man [Ford] was," he said in a 2007 interview for the Richard Nixon Presidential Library. James Cannon, a senior adviser to Ford, told NPR's Madeleine Brand the president was a "workhorse," and while he may have never sought the presidency, Ford possessed two qualities that were essential for the job: "a practical mind and a noble heart."

Donald Rumsfeld, who was Ford's chief of staff from 1974 to 1975, offered his thoughts on the president in a statement after his death in 2006. He wrote, "his personal character helped restore the reservoir of trust in the government," reported the American Forces Press Service. While Ford was lampooned on "Saturday Night Live," in an article for KERA News, Merrie Spaeth, who worked in the Reagan administration, wrote, "President Ford took a back seat to no one in many areas, including humor."

Richard Nixon

Almost everything Richard Nixon accomplished as president, from his inauguration in 1969 to his resignation in 1974, was erased by a single issue. During his tenure, the Vietnam War expanded, but he also scored foreign policy victories with China, while at home he boosted social programs and established the Environmental Protection Agency. Then came Watergate, and the rest is history. While historians and journalists have said plenty about Nixon, former staffers have too.

H.R. Haldeman, who was Nixon's chief of staff until 1973, variously described his boss in the book "The Ends of Power" as "dirty" and "mean" as well as "coldly calculating" and "craftily manipulative," adding he was "the weirdest man ever to live in the White House." Alexander Butterfield, deputy assistant to the president, had a different view, telling Story Corps: "Nixon was a very controlled person. He was so disciplined."

In 2007, Alexander Haig, Nixon's former chief of staff, gave a lengthy interview for The Richard Nixon Presidential Library, and said he was "the most thoughtful, considerate and I think intelligent president of them all." Haig said once Nixon made a decision, he never U-turned, describing it as "a good trait to have." Henry Kissinger, the president's national security advisor, told CNN's Fareed Zakaria in 2022 Nixon was able to make "extremely courageous decisions" (including spying on his own family) but "found it very difficult to give orders to somebody he knew disagreed with him."

Lyndon B. Johnson

Former Democratic leader Lyndon B. Johnson was a surprise addition to the presidential campaign ticket in 1960, and was sworn in as vice president in January 1961. There he would have stayed, chafing against a position he disliked, overseen by the Kennedys, who could not stand him, had history not taken a different course. Following John F. Kennedy's assassination in 1963, Johnson became the 36th president of the United States. Despite the tragic start, his tenure is regarded as successful, marked by important legislation extending environmental and social protections.

The man himself was not easy to work with, as several staffers confirmed in a slew of books. In 1964, Johnson discussed the appearances of female White House employees with special assistant Ralph Dungan in a recorded call, according to National Post, and was known for vulgar habits, including prolific cursing. In his book "Remembering America," Johnson's speechwriter Richard Goodwin worried the president was buckling under the pressure of the Vietnam War, after his "always large eccentricities had taken a huge leap into unreason," adding he felt it was "paranoid behavior."

Other former staffers take a more appreciative view. In the book "Indomitable Will: LBJ in the Presidency" by Mark Updegrove, special assistant Jack Valenti revealed that, although working with Johnson was grueling, it was also "the summertime of our lives." Special assistant Doug Cater was quoted as saying, "It was life with Big Daddy, and Big Daddy could beat you one moment and then hug you the next."

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy held office for just 1,037 days but achieved much in that time. Major wins included the 1963 Equal Pay Act and dealing with the Cuban missile crisis, though the 1961 Bay of Pigs scandal blotted his copy book, as did his womanizing ways. Kennedy allegedly romanced everyone from Hollywood stars to White House secretaries, though it wasn't an issue for many women employees. Sue Mortensen Vogelsinger told WBUR, "I was so happy being where I was, it was the most exciting job in the world."

Even male staffers were dazzled by Kennedy. Describing the night he first met him, on the eve of his assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson's aide Jack Valenti told Vanity Fair the president looked like a "Plantagenet warrior, a great royal king. Handsome, charming." Michael Blumenthal, who was a trade advisor to Kennedy, stated that he "had political courage, a scarce commodity in politics" (per Princeton Magazine).

Arguably one of the people who knew Kennedy best was Pierre Salinger, his press secretary. He told Eileen Prose in a 1983 interview that the president had a "marvelous," "self-deprecating" sense of humor, and his ability to defuse a tense situation "made him so easy to work with." Salinger added that one of Kennedy's strengths as president was his ability to engage people and make them feel as if they were "participating in government."

Dwight D. Eisenhower

After being appointed supreme commander of both the Allied Expeditionary Force and then NATO, Dwight D. Eisenhower probably didn't think his star could rise much higher — but it did. He served as United States president from 1953 to 1961, a tumultuous time that saw the rise of McCarthyism, the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, and the creation of NASA.

Eisenhower had lots of military experience but considerably less political know-how, though that didn't impact his popularity with the American public. Among Democrats, including John F. Kennedy, it was not the same story. Former White House chief of staff Sherman Adams said years later: "I'm very distressed at this tendency of academics to look down their noses at the Eisenhower administration," according to "The American President" by William E. Leuchtenburg (per vdoc.pub).

The book also quoted Eisenhower's aide Emmet Hughes, who claimed the president was "never more decisive" than when decided not to do something that contradicted his personal beliefs of that of the office he held. E. Frederic Morrow, the first African American to become a presidential aide, spoke about his attempts to engage Eisenhower on issues affecting Black communities. In his book "Black Man in the White House," he wrote that the president's "lukewarm stand on civil rights made [Morrow] heartsick," and called Eisenhower's lack of action "the greatest cross [Morrow] had to bear."

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt held the American presidency for 12 years, dealing with a range of massive challenges, from appearing to overcome his own physical disability and helping the country recover from the Great Depression, to the United States entering — and helping to win — World War II. His long-time political advisor Louis Howe recognized "his seriousness, his earnestness, his firm dedication to his cause," during their first meeting in 1911. He wrote, "I made up my mind that he was Presidential timber" (via PBS).

Those qualities came across in his now-legendary "Fireside Chats," carefully scripted radio broadcasts to the American people that offered a less formal way for Roosevelt to focus on a particular topic. According to "Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal" by William E. Leuchtenburg, Frances Perkins, Roosevelt's secretary of labor, said, "His face would smile and light up as though he were actually sitting on the front porch or in the parlor with them" (via StudyLib).

Not all staffers enjoyed working with the industrious president. In an address to the Rotary Club of Elmsford, Richard J. Garfunkel said General Douglas MacArthur, who was Roosevelt's chief of staff, after angrily confronting the president about proposed cuts to the military, admitted: "I thought my army career was at an end," and offered his resignation. Roosevelt turned him down, but the encounter made McArthur physically sick.

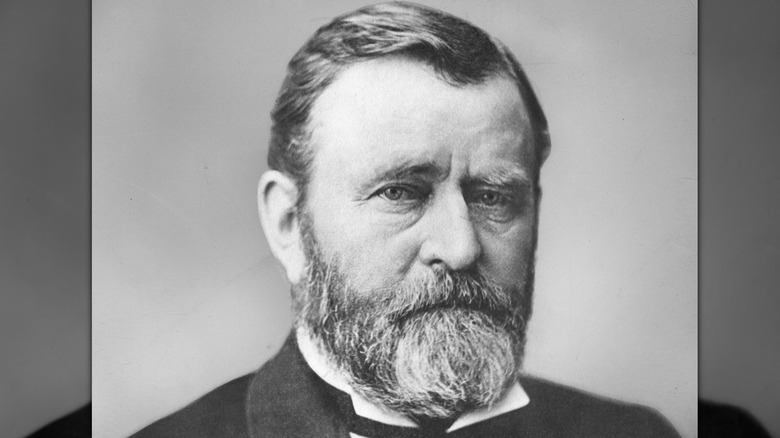

Ulysses S. Grant

In four years, Ulysses S. Grant went from commanding a volunteer regiment in Missouri to general-in-chief of the Armies of the United States, accepting General Robert E. Lee's surrender in 1865. Three years later, in a landslide victory, Grant became the country's 18th president. Although his administration was dogged by scandal and corruption, Grant was never found to be personally involved, allowing his reputation as an honest man to remain intact.

Historians such as Henry Adams have said that Grant's abilities as a general did not carry over to the presidency. One man who had first-hand experience of Grant's true temperament was John Aaron Rawlins, his general and secretary of war. In a letter to Grant, Rawlins wrote: "I again appeal to you in the name of everything a friend, an honest man, and a lover of his country holds dear, to immediately desist from further tasting liquors of any kind" (per The New Yorker).

The pressures on Grant were huge, particularly following Andrew Johnson's unpopular presidency. But, as Secretary of the Treasury George Boutwell pointed out, Grant was not above admitting he was wrong. Boutwell wrote: "He was so great that it was not a humiliation to acknowledge a change in opinion, or to admit an error in policy or purpose," while Postmaster General John A.J. Creswell said, "The more I see of him the more devotedly do I admire and love him" (via White House History).

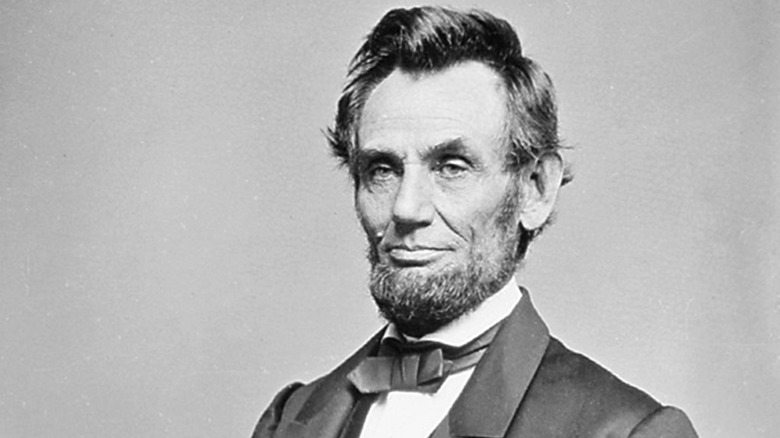

Abraham Lincoln

Millions of words have been written about the life and death of Abraham Lincoln, whose time in the White House was dominated by the American Civil War. Although the cabinet working with him at this time were not always easy bedfellows, Charles A. Dana, assistant secretary of war, described them as "men of extraordinary force and self-assertion" in his book "Recollections of the Civil War." Dana said Lincoln was "calm, equable, uncomplaining" and "pleasant and cordial" to everyone, but "they all felt it was his word that went at last."

Two men with unique insights into President Lincoln were his "boys," private secretaries John Nicolay and John Hay. They lived at the White House and witnessed momentous events including the Gettysburg Address and the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. They also — according to Hay — kept Lincoln organized. In 1866, he said in a letter to William Herndon: "He was extremely unmethodical; it was a four-years struggle on Nicolay's part and mine to get him to adopt some systematic rules" (via Mr Lincoln's White House).

William H. Seward, the president's first secretary of state, was an ambitious man with much in common with Lincoln. He tried to undermine him politically but was thwarted by the president, though they remained friends. After the assassination, John Hay wrote that Seward said: "Lincoln always got the advantage of me, but I never envied him anything but his death" (via Abraham Lincoln's Classroom).

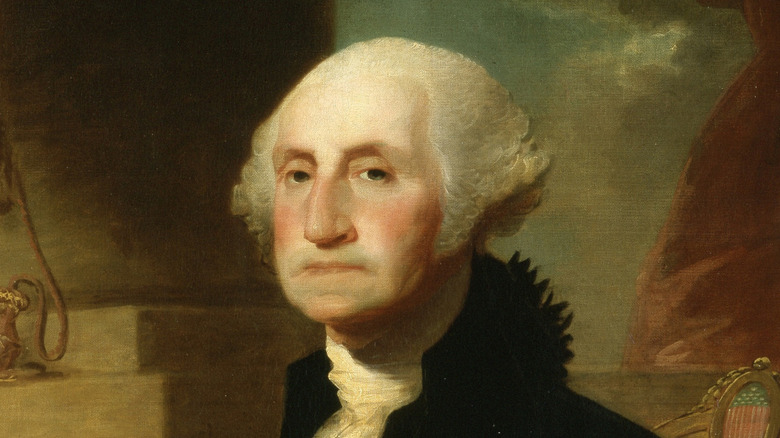

George Washington

As the very first president of the United States, George Washington was in office from 1789 to 1797, presiding over a country almost as new as his position was. It didn't take long for his cabinet to start squabbling, and as the political divisions grew ever wider, he reluctantly accepted a second term in office. Washington declined a third – though it wasn't his biggest regret.

At his inaugural address, Thomas Jefferson, who bitterly opposed the office of the presidency and many of Washington's policies, said his predecessor was "our first and greatest revolutionary character ... whose preeminent services had entitled him to the first place in his country's love and destined for him the fairest page in the volume of faithful history," per Washington's Mount Vernon. Fellow founding father John Adams was satirical in his assessment of Washington, deeming a "handsome face," wealth, and being a Virginian among his many talents in an 1807 letter to Benjamin Rush.

Thanks to the smash-hit "Hamilton" musical, we know more about cabinet member Alexander Hamilton. He worked as an aide to Washington before an argument in 1781 prompted him to leave, later writing about his employer. "three years past I have felt no friendship for [him] and have professed none." Eight years later, as president, Washington made Hamilton his treasury secretary. (via PBS). In 1799, after the president's death, Hamilton wrote, "He was an aegis very essential to me."