The Worst U.S. Generals That Nearly Cost Us Our Freedom

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

War has been a consistent thread in the story of the United States of America, right from the start. The country was created in 1776, one year after the start of the Revolutionary War, and since then, it has been embroiled in more than 10 conflicts. Some, like the Civil War, took place on home soil, while others were played out on foreign, very hostile shores. But they all required reliable intelligence and leadership from the highest ranks of the U.S. military.

History is peppered with the names of famous generals who planned and led successful military campaigns, covering themselves — and their superiors — in glory. Yet there are other holders of the same rank who managed to do anything but. Incompetence, inflated egos, and an inability to command difficult situations have left very different legacies for these military men. Here's a closer look at 12 of the worst U.S. generals from infamous wars.

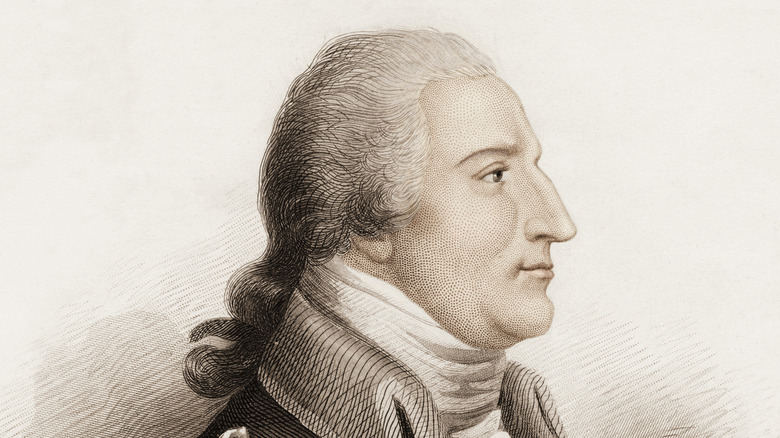

Benedict Arnold: The Revolutionary War

His name has gone down in history as a byword for treason, but Benedict Arnold initially supported the American cause. Born in 1741, he escaped a dissolute childhood to become a successful businessman. Thin-skinned and quick to criticize others but undoubtedly zealous, Arnold threw himself into the American Revolutionary War after the death of his first wife in 1775. George Washington rewarded his service in 1778 by granting him command of the city of Philadelphia, where, a year later, Arnold married Peggy Shippen.

As well as irritating several officers in the Continental Army, Arnold also became a target of patriot Joseph Reed, president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. His relentless campaign to discredit Arnold, coupled with severe financial issues, eroded the latter's faith in an independent America, and it was soon replaced by Peggy's staunch pro-British sentiments. After resigning his Philadelphia command, Arnold played on his leg injury and persuaded Washington to give him command of West Point.

From there, Arnold secretly contacted Major John Andre and began deliberately weakening West Point's defences. The pair plotted to get plans of the site to the British via Andre, but while the latter was caught and executed, Arnold escaped and was named a British brigadier general just days later. He later wrote to Washington claiming he switched sides for "love of my country," per Americana Corner.

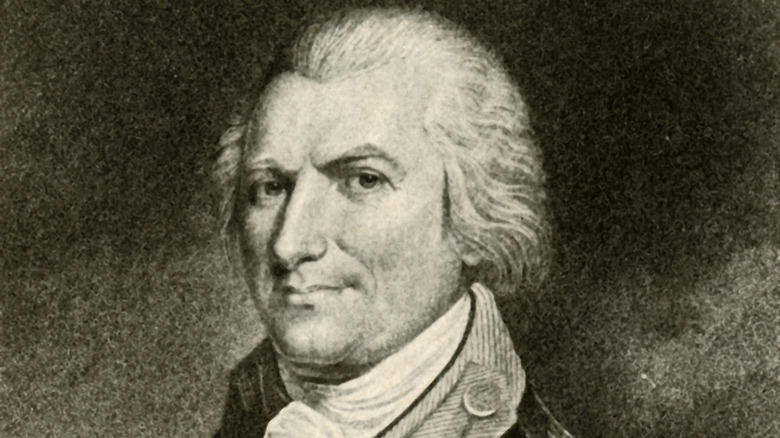

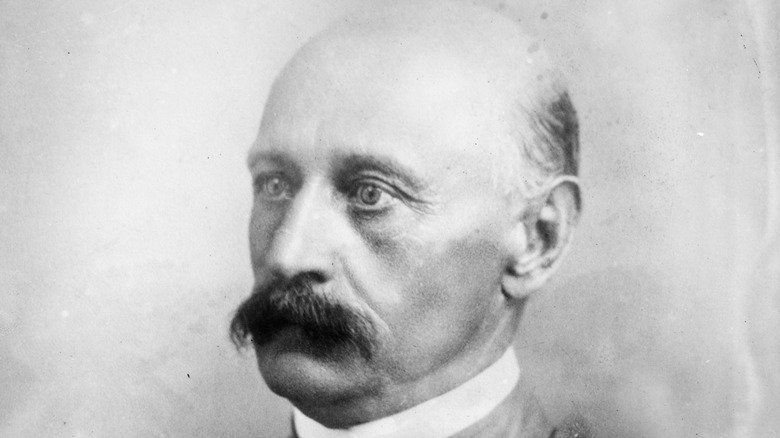

Arthur St. Clair: The Northwest Indian War

Arthur St. Clair was born in Scotland in 1736 and had already seen active service in the French and Indian War when he decided to put down roots in Pennsylvania, becoming a major landowner. He supported America's fight for independence and eventually became a colonel in the Continental Army. In 1777, shortly after being promoted to brigadier general, St. Clair's advice helped Washington secure Princeton from the British.

His reward the same year was command of Fort Ticonderoga. The inexperienced St. Clair blundered by posting his men inside the fort, leaving it vulnerable to British cannons. The subsequent loss of Ticonderoga saw him court-martialed. Despite this, he remained in military service and, as governor of the Northwest Territory, concluded the Treaty of Fort Harmar, which grabbed Native American lands and forced the tribes to leave.

In 1791, St. Clair led around 2,000 demoralized and poorly armed forces to quell local tribes. However, almost of his men had deserted by the time their enemy launched the surprise attack Washington had previously warned of. The ensuing bloodbath killed around a quarter of the American army. Washington later said of his general: "Oh, God, he's worse than a murderer," via The Washington Post. "St. Clair's Defeat" led to the first-ever congressional investigation of the executive branch, while the general, his reputation in tatters, died penniless in 1818.

William Hull: The War of 1812

As an officer and a major of the Continental Army, William Hull won the approval of several senior officers during the Revolutionary War. Little did he know how important that would be. After the war, Hull moved to Massachusetts and entered politics before President Thomas Jefferson named him governor of the Michigan Territory in 1805. However, the position brought him into conflict with local Native Americans, following tribe resettlement.

In 1812, Hull, then nearly 60 and keen to maintain his political career, accepted the rank of brigadier general and led the 4th infantry and Ohio militia in the invasion of Canada. From the start, the campaign was doomed. Hull's men were poorly disciplined and lacked equipment, while the British captured much of their supplies and, more damagingly, Hull's personal papers, including plans for his forces. Although he crossed the border into Canada, he quickly retreated to Fort Detroit.

After isolating the fort, British Major General Isaac Brock and Native American leader Tecumseh fooled Hull into believing he was outnumbered — the opposite was true — and to their astonishment, the cowed general agreed to Brock's demands for surrender rather than fight it out. He was swiftly court-martialed and sentenced to death for neglect of duty. President James Madison granted him a pardon, based on his younger years in the army, but Hull spent the rest of his life trying to restore his reputation.

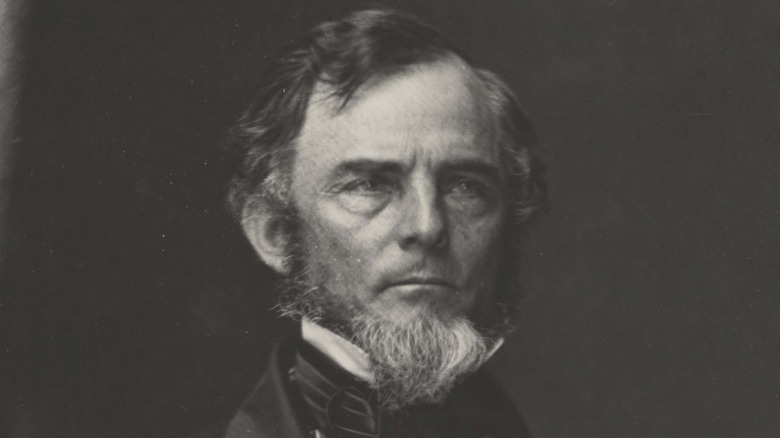

Gideon Pillow: The American Civil War

In their book "The Life and Wars of Gideon J. Pillow," authors Nathaniel C. Hughes Jr. and Roy P. Stonesifer wrote: "Fame chose Gideon Pillow as her darling and laid opportunities at his feet like golden apples, but he kicked them aside." Born in 1806, Gideon Johnson Pillow's connections with the underrated President James K. Polk helped him secure the rank of brigadier general during the Mexican War. He would prove utterly unfit.

After digging trenches on the wrong side of the Camargo fortifications, Pillow inflated his role in the victories at Contreras and Churubusco for the newspapers. The claims infuriated General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, and the two men feuded for the rest of their days. When the Civil War broke out, Pillow was a brigadier general in the Confederate Army at the Battle of Belmont — Ulysses S. Grant's first clash — and he performed well enough to receive the Confederate Congress' thanks and temporary command of Fort Donelson.

After Pillow ordered a foolhardy retreat, the fort came under attack in 1862, and senior officer John B. Floyd turned over command to him. Before fleeing, Pillow passed it to Simon Bolivar Buckner, who summarily surrendered the fort to Grant. The following year, while in command of Tennessee volunteers on the last day of Stones River, Major General John C. Breckenridge allegedly found Pillow hiding behind a tree instead of leading the Confederate charge. It should be noted, however, that some historians contest this account, pointing to scant evidence.

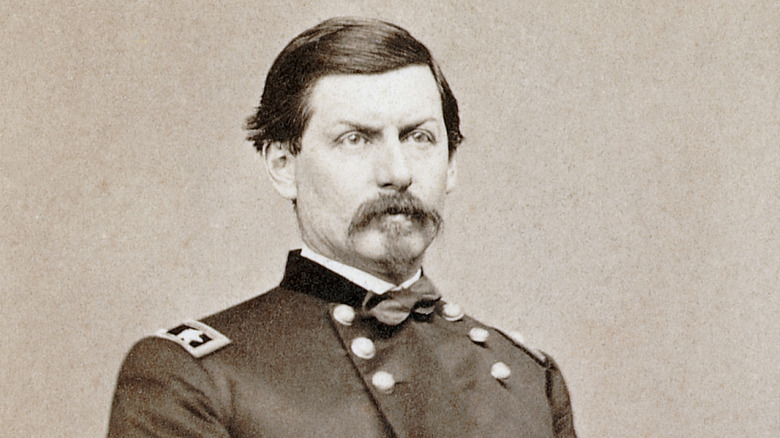

George B. McClellan: The American Civil War

There is no doubt that George B. McClellan was an intelligent man. He graduated second in his class at West Point and was a natural leader, organizer, and administrator. But McClellan also possessed a massive ego, and, throughout his military career, he would inflate the odds against him, cast himself as the country's savior, and belittle those around — and above — him.

In 1861, after a success at the Battle of Rich Mountain, Lincoln appointed McClennan major general, and while it was followed by the Union loss at Bull Run (one of the Civil War's biggest blunders), McClennan was handed total command of the Army of the Potomac. Dubbed "Napoleon" in the press, McClennan felt he was the man of the moment, readily criticizing others, including President Lincoln, who he called "the gorilla."

In "Father Abraham," author Richard Striner describes the "brittle veneer" of his bravado, describing McClellan as "weak to the point of timidity." During the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, he constantly delayed, while Robert E. Lee's relentless attacks forced McClellan to abandon efforts to take Richmond. McClennan's decision to stay put after the Battle of Antietam again exposed his inertia, and in October, twice he disobeyed Lincoln's orders to move the army. In early November 1862, McClellan was removed from his command on the orders of the president.

General Jacob H. Smith: The Philippine-American War

The Philippine-American War lasted from 1899 until 1902 and came hot on the heels of the Spanish-American War, after which the Philippines colony was passed to American control. The independence movement, led by Emilio Aguinaldo, which had previously supported the U.S., was outraged when Filipinos were not recognized. Conflict broke out, and President William McKinley annexed the archipelago.

Into this volatile situation strode General Jacob Hurd Smith, as head of the 1902 Samar Campaign. It began with a 1901 attack on the town of Balangiga, in which 54 American soldiers were killed. In response, Smith denied residents the right to leave, cut off food supplies so they didn't reach insurgents, and burned villages and crops before Smith turned his attention to the locals.

He ordered Major Littleton W. T. Waller to: "Kill and burn; the more you kill and burn the better it will please me," he said, per Scioto Historical. He specified Waller should "kill everyone over ten" and, in a later written order, demanded "the interior of Samar must be made a howling wilderness." Although he received a hero's welcome on his return to the U.S., General Smith was court-martialed for "conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline," with a recommendation for an "admonishment," via The New York Times. President Theodore Roosevelt took the rare step of retiring him from active duty.

John J. Pershing: World War I

A Pulitzer Prize winner and only the second man to be granted the title general of the armies, John J. Pershing has earned a reputation as a fine military leader. But scratch the surface of his time as commander of the American Expeditionary Force and it's a different story. He arrived in France in 1917, where he was informed that, not only were the Americans short on guns, the bayonet as a weapon of war was "obsolete." "Speak for yourself," Pershing wrote.

Despite losing thousands of men in clashes at Belleau Wood and Soissons, Pershing and other senior American officials continued to send men out at a slow walk toward the enemy "with no apparent attempt to utilize cover," per Smithsonian Magazine. But Pershing's stubborn refusal to change tactics wasn't the only black mark against his name.

In "Betrayal at Little Gibraltar," William Walker recounts how Pershing actively encouraged competition between major generals George Cameron and Robert Lee Bullard. Their rivalry would have deadly consequences for the men of the 79th Division, pinned down by the Germans at the village of Montfaucon. After the war ended, Pershing was questioned by the House of Representatives Committee on Military Affairs about whether he sent men "over the top" to their deaths after the Armistice. Pershing said he had no idea hostilities had ended and was merely following orders.

Douglas MacArthur: World War II

Some say General Douglas MacArthur was deservedly one of the United States' most decorated officers. But poor decision-making and monstrous ego were two elements of MacArthur's character that overshadow this acclaim. Notably, he teargassed World War I veterans in 1932 and failed to move American planes in the Philippines after the Pearl Harbour attack, leaving them sitting ducks for the Japanese. And though MacArthur followed orders to quit Bataan and Corregidor during World War II, he left his men to face the humiliation of surrender — the murderous Death March and years in Japanese death camps. He also planned to invade the Pacific island of Mindanao, and as thousands of U.S. Marines died trying to capture a vital runway at nearby Peleliu, MacArthur changed his mind.

Things got worse during the 1950 Korean War. After capturing Seoul, MacArthur decided to press on to the border with China, ignoring intelligence that warned that 300,000 troops were being massed ahead. The result was a crushing withdrawal. When MacArthur began calling for atomic bombs to be used against China, President Harry Truman removed him from duty. In the book "Plain Speaking," he told Merle Miller: "I fired him because he wouldn't respect the authority of the President. That's the answer to that. I didn't fire him because he was a dumb son of a b****, although he was, but that's not against the laws for generals."

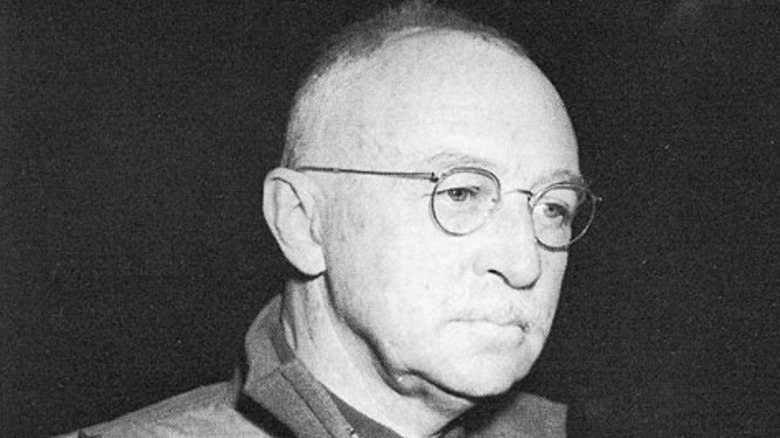

John P. Lucas: World War II

In January 1944, American Major General John Lucas was feeling every one of his 54 years when he was chosen by Lieutenant General Mark Clark to lead an amphibious assault against Anzio. Operation Shingle was part of a wider plan for Allied forces to capture Rome from the Germans, but Lucas was skeptical of it from the start. He wrote in his diary: "The whole affair has a strong odor of Gallipoli and apparently the same amateur was still on the coach's bench," via Warfare History Network.

Despite his belief that he lacked the men and equipment to carry out his orders, and following a catastrophic rehearsal, the landing on January 22 at Anzio was a success, meeting with little German resistance. That's when the problems began. Lucas remained on the beach, fortifying his position but — crucially — not pushing into the Alban Hills, where he had been explicitly ordered to cut off German communications.

Days before the operation, Lt. General Clark urged Lucas not to "stick his neck out" and reminded him of his own brush with disaster at Salerno after he moved too fast. So Lucas waited, and while he did, the Germans reorganized their defences around Anzio and further afield. As the weeks passed, Allied casualties in the region mounted, and patience with Lucas ran out. His reputation as a general tarnished, memorializing him as one of the worst generals of World War II, and he was relieved of his command on February 22.

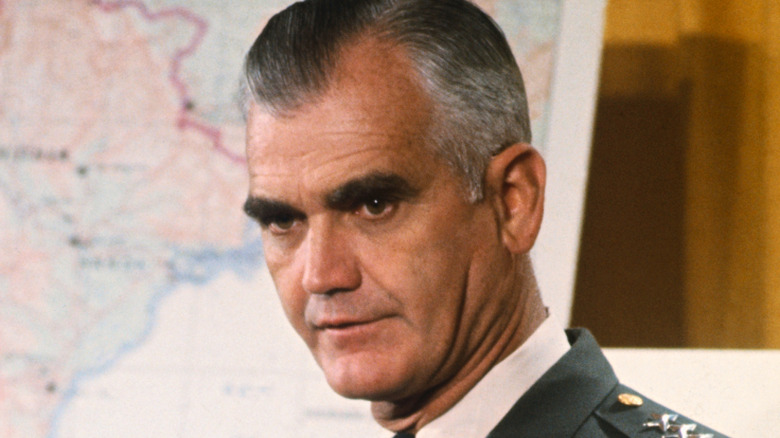

William Westmoreland: The Vietnam War

Proof that there is a vast gulf between looking the part and being suited for a high-end military position comes in the form of General William Childs Westmoreland. This square-jawed veteran of World War II and the Korean War commanded U.S. forces in Vietnam between 1964 and 1968, but history has found him wanting.

His approach to the complexities of the Vietnam War was one of relentless attrition: To keep throwing more firepower and men at the enemy until they were defeated. However, as noted in Lewis Sorley's book "Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam," a senior officer said the general "never understood the war," and this is why his bloody strategy would ultimately not pay off. If that wasn't bad enough, Westmoreland didn't fully back the official program for the pacification and long-term development of Vietnam, known as PROVN, leaving the South Vietnamese poorly armed and unsupported for too long. Even worse, when intelligence about vast enemy numbers massing against Tet in 1968, Westmoreland — and others — ignored it, with catastrophic results.

Following the disaster at Tet and with domestic support for the Vietnam War nosediving, Westmoreland did the unthinkable: He misled President Lyndon B. Johnson about the success of his attrition campaign and asked for over 200,000 additional troops. Johnson refused the request, and Westmoreland was swiftly replaced by General Creighton Abrams.

Tommy R. Franks: The Iraq War

Weeks after the 9/11 attacks on the United States, Osama bin Laden and his terrorist group al Qaeda were identified as the culprits. They became the targets of the Bush Administration's War on Terror, which included the December 2001 Battle of Tora Bora in Afghanistan. The CIA were certain they had Bin Laden in their sights and pleaded for Army Ranger support, but their request was denied by General Tommy Franks.

A few months later, he refused to send in troops during Operation Anaconda, also in Afghanistan, where al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters were cornered. Like bin Laden, the Taliban were able to escape to Pakistan, but according to Franks, "the result of the operation was also outstanding," via The Atlantic. In 2003, General Franks led the invasion of Iraq, and while his "basic grand strategy" focused on starting the conflict, he had no plans on how to end it, establish stability, and hand over control to Iraqi authorities.

Even before the invasion, Franks had shrugged off concerns about the low number of U.S. troops being deployed. The then-retired Franks said in a 2004 interview with CBS: "We opted to go with a smaller force and a plan to build the force as necessary over time." However, Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez claimed Franks told him American soldiers would be gone by the end of 2003. Complete U.S. withdrawal took until December 2011.

Ricardo Sanchez: The Iraq War

In Thomas E. Ricks' 2012 "General Failure" article for The Atlantic, he described General Ricardo Sanchez, the man who succeeded Tommy Franks as commander of U.S. ground forces in Iraq, as a "tragic figure," a "mediocre officer," and an "inveterate micromanager." While General David Petraeus was flexible and able to adapt to the complex situation in the country, Sanchez was not. Ricks noted that then-Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage said to himself: "This guy doesn't get it." But worse was to come.

It was during Sanchez' tenure that thousands of Iraqi prisoners were illegally detained and sent to what would become the notorious Abu Ghraib prison. While he initially regarded it as a "breakdown of discipline" and denied giving the green light to their actions, the 2008 Senate Armed Services Committee report concluded differently. It said the abuses at Abu Ghraib were "not simply the result of a few soldiers acting on their own" but were "approved by Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, and dubbed the practices "an erosion in standards dictating that detainees be treated humanely."

The scandal prompted Sanchez to retire in 2006, and in his book "Wiser in Battle," published the same year as the committee report, he called the Iraq invasion a "strategic blunder of historic proportions." As reported by The Atlantic, Sanchez hit the headlines in June 2020 when he told David Reed that President Donald Trump was "a racist."