The FBI's Deadly War On Depression-Era Gangsters

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The years between the start of Prohibition in 1920 and the christening of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1935 were among the most violent in United States history. Gangsters roamed cities, bitterly fighting for control of gambling, bootlegging, and protection rackets. In rural areas, outlaws robbed banks and wreaked havoc. Both groups relied on advances like the automobile and the Tommy gun, and many became household names thanks to newspaper and radio reports.

A turning point came in 1929. In February, the American public, long hardened to the violence, was shocked by the gruesome St. Valentine's Day Massacre. Months later, when the Wall Street crash in October left millions destitute, the stage was set for a fresh wave of criminality — and a new breed of lawmakers.

So began the American era of the "Public Enemy," a term reportedly coined by Frank J. Loesch, who was chairman of the Chicago Crime Commission from 1928 to 1938. It was more or less over by 1935, but in that time, the bureau gained new powers, used innovative detection methods, and turned little-known lawyer J. Edgar Hoover into a figure synonymous with justice and the FBI's deadly war on Depression-era gangsters.

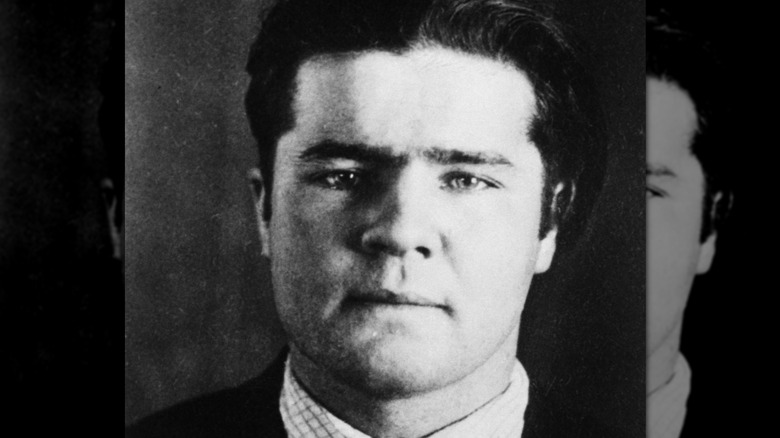

Charles Pretty Boy Floyd

Born in 1904 in Georgia, Charles Floyd (nicknamed "Choc" after his favorite beer) had his first brushes with the law as a teenager. He tried his hand at bootlegging and was taken under the wing of notorious fence John Callahan before becoming a husband and father. In 1925, a St. Louis robbery netted Floyd almost $12,000 — and five years in jail.

Released in 1929, a newly divorced Floyd met Beulah Baird, who dubbed him "Pretty Boy," and he embarked on a spree of over 30 bank robberies across the Midwest. While the police were powerless to stop him, the public adored him. Myths circulated that Floyd tore up mortgage papers at the banks he robbed, and he became known as "Robin Hood of the Cookson Hills." On a postcard sent to the Oklahoma governor, Floyd claimed: "I have robbed no-one but moneyed men," via The Oklahoman.

To J. Edgar Hoover, a rising star in the FBI, Charles "Pretty Boy" Floyd was nothing less than "Public Enemy Number One." Whether he was involved in the 1933 Kansas City Massacre is disputed by historians, but that incident nevertheless led to a major shift in how criminals were targeted — and Floyd's death at the hands of law enforcement officials a year later.

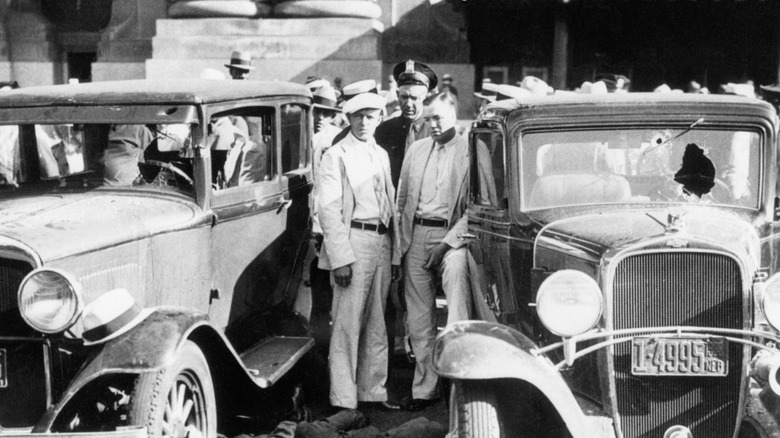

The Kansas City Massacre

Frank "Jelly" Nash was a thief and safe-cracker with a 20-year criminal career. His first offence was a 1913 murder — but the life sentence was cut to 10 years after he signed up for World War I. He was jailed again in 1920 for burglary and using explosives, though the 25-year term was also reduced thanks to good behavior. Upon his release in 1922, Nash joined the Al Spencer gang, robbing the Katy Limited postal train in Oklahoma the following year.

Again, Nash received a 25-year sentence but brazenly escaped Fort Leavenworth in 1930 after being allowed to run an errand. More lawbreaking followed, including helping seven inmates to escape Leavenworth. By 1933, Nash ended up in Hot Springs, Arkansas. When FBI agents learned he was in town, they quickly joined police chief Otto Reed, who had the legal authority to arrest Nash.

All four boarded an overnight train for Union Station in Kansas City, Missouri. The next morning, they were met by more officers, but while loading Nash into a car, three gunmen — allegedly including Charles "Pretty Boy" Floyd — killed him and four law enforcement officials. What became known as the Kansas City Massacre prompted Congress to pass laws beefing up the weapons carried by agents, finally allowing J. Edgar Hoover's FBI to take the fight to members of organized crime.

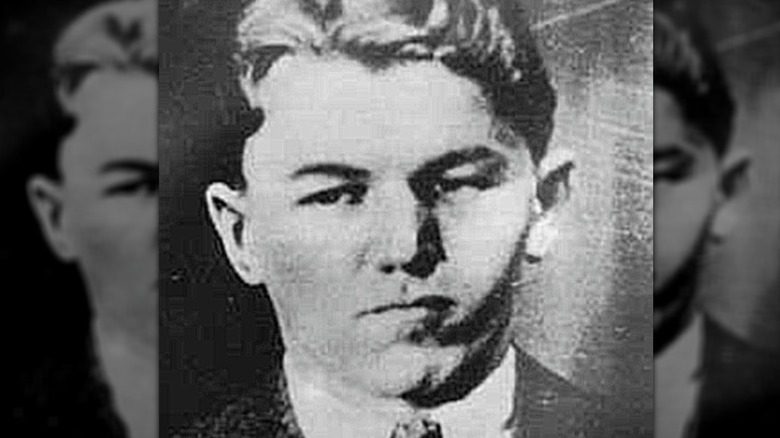

George Baby Face Nelson

Chicago-born Lester Gillis was a seasoned car thief by the time he was 14 years old, earning his nickname "Baby Face Nelson," yet proving too violent for Al Capone. By 1931, he was in jail for one bank heist and being tried for another when he escaped and fled to California. There he met long-standing partner in crime John Paul Chase. Nelson was subsequently implicated in two apparent murders and briefly worked with John Dillinger and his gang.

In 1934, after Nelson killed an FBI agent, a reward was issued for his capture or arrest. He was involved in the deaths of more police officers the same year, and after Dillinger was fatally ambushed, Nelson and Chase stole a car in Chicago and decided to get out of town.

However, they reckoned without Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, a B.I. agent who was tipped off about Nelson and the stolen vehicle. When the car was spotted in Barrington, Illinois, Cowley and Special Agent Herman Edward Hollis headed to the location. A gunfight ensued in which both lawmen were killed. Chase and Nelson took the agents' car, but the latter was fatally wounded, despite wearing body armor. He died that evening.

Bonnie and Clyde

Solid detective work and the transport marvel of the age — the motor car — first put the Bureau of Investigation onto Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow in 1932. A prescription bottle, found in a vehicle they had stolen, led the FBI to the criminal couple and their gang, prompting a warrant for their arrest.

The couple had met in West Dallas in 1930, shortly before Clyde was jailed for car theft. Bonnie proved her love by helping him in a short-lived escape, but after two years (during which he committed his first murder that another inmate took the blame for), he was released. Bonnie and Clyde, alongside their ever-evolving gang, embarked on a crime spree that included stealing cars, robbery, kidnapping, and indiscriminate murder.

Unlike some Depression-era criminals, the notoriously violent couple were not well-regarded by the public, and by 1934, the net around them was closing in. They made headlines with a jailbreak at Eastham Prison Farm, and afterward, the duo headed to Louisiana's Bienville Parish. Little did they know a police ambush was lying in wait: Bonnie and Clyde's criminal careers ended in a fatal hail of bullets.

The Barker-Karpis Gang

Fred Barker was one of four boys born to Arizona (aka Kate) "Ma" Barker, who spent much of her time trying to get one or more of them out of prison in the 1920s. While behind bars in 1931, youngest son Fred met Alvin "Creepy" Karpis, and after getting out of jail, they teamed up to hold up banks, steal from trains, and commit murder across the Midwest.

The Barker/Karpis gang made their names with two high-profile kidnappings. In 1933, they secured a $100,000 ransom for brewery owner William A. Hamm, Jr. and reaped twice that figure the following year for millionaire Edward Bremer. But the criminals reckoned without the investigative smarts of the B.I. Technical Crime Laboratory.

Founded in 1932 and driven by Special Agent Charles Appel and J. Edgar Hoover, it was expanding the field of forensic detection, including the use of fingerprints. The agents at the B.I. Lab were able to take latent fingerprints from the ransom notes sent to Hamm's family and connect them to Barker/Karpis gang. In 1935, after a shootout with B.I. agents, Fred and "Ma" Barker were killed, while Karpis – who had his fingertips surgically removed to avoid detection — was arrested a year later.

The Lake Weir Shootout

In his 1938 book "Persons in Hiding," J. Edgar Hoover insisted that Kate "Ma" Barker was "the most vicious, dangerous, and resourceful criminal brain of the last decade," and was as a "monument to the evils of parental indulgence." While forensic evidence tied her son Fred to the kidnappings of William A. Hamm Jr. and Edward Bremer, there wasn't a shred of proof his mother was involved. Would justice prevail?

When Arthur "Doc" Barker, the third of four Barker brothers, was arrested in Chicago on January 8, 1935, FBI agents were delighted. He had a map that led law enforcement officers to the exact place where his younger brother Fred and "Ma" Barker were holed up: Lake Weir, in Marion County, Florida.

A team led by Agent Earl Connelly soon had the house with the Barkers inside surrounded, and at around 5 a.m. on January 16, a six-hour gun battle began, during which as many as 1,500 rounds were fired. When it ended, both Fred and Ma Barker were dead. Ironically, a memo to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent out that same day said of the matriarch: "She has no criminal record apparently."

Al Capone

During the 1920s, Al Capone made a name for himself and a fortune from a string of illicit enterprises, including bootlegging booze and drug running, murdering anyone who stood in his way. As he built up his criminal enterprise during the Great Depression, Capone also offered help to the city's poor, running a soup kitchen for the needy.

While some people saw him as a Robin Hood-like figure, as the FBI's Public Enemy No. 1, federal agents had no such illusions. For years, J. Edgar Hoover and the Bureau were all-but powerless to stop Capone's illegal activity. He was jailed in 1929 for carrying a concealed deadly weapon, released after nine months, but imprisoned again in 1931 for six months on contempt of court charges.

He always seemed to slip through the fingers of the justice system. Making matters worse, Hoover and Eliot Ness, the man who would later claim to have brought down Capone, did not get on. It was only when President Herbert Hoover overhauled federal criminal law, the courts, and prison systems that officials finally got the upper hand. In the end, it was a failure to pay income tax on his ill-gotten gains that saw Capone jailed in 1931. He died in 1947, aged just 48.

Frank Nitti

In Depression-era America, gangsters were every bit as ruthless as kings when it came to seizing and retaining power. But the rise of Frank Nitti was a rare instance where a transfer happened bloodlessly. Known as "The Enforcer" because of his ability to handle figures and money, Nitti was a close family friend to Al Capone, and after an 18-month spell behind bars for tax evasion, he soon became indispensable to the crime boss.

When Capone was imprisoned in 1931, Nitti was his natural successor and quickly became a target for law enforcement. However, he became proof that breaking the rules was not an option for the police. In 1932, Nitti was shot during a raid ordered by the new Chicago mayor, Anton Cermak, and was framed for shooting one of the senior officers taking part. When Cermak's involvement in the raid emerged during the trial, the case against him collapsed, and Nitti was acquitted.

Notoriety still beckoned for Nitti, thanks to a blackmail scheme targeting theater owners that began in 1933 with George E. Browne and Willie Bioff. Nitti seized his chance to turn the screws on Tinseltown and extorted $1 million from major old Hollywood studios, including Paramount, 20th Century Fox, and Warner Bros. In 1943, a diminished Nitti died by suicide.

George 'Machine Gun' Kelly

Many sources have claimed that George Kelly Barnes — aka George "Machine Gun" Kelly — uttered the immortal line: "Don't shoot, G-Men!" It's likely he never said any such thing during his 1933 arrest for kidnapping, his most infamous crime. No matter the truth, the nickname stuck, and "G-Men" was forever aimed at Bureau of Investigation agents.

The phrase has also overshadowed the incredible work done by the FBI in the lead-up to George "Machine Gun" Kelly's capture. In July 1933, he had abducted wealthy Charles Urschel from his home at gunpoint. Urschel's wife immediately telephoned J. Edgar Hoover himself for help, but the bureau did not leap into action until after the $200,000 ransom was paid and Urschel was released.

The FBI embarked on a nationwide investigation that put George Kelly and his wife, Kathryn, in the spotlight almost from the start. Their cohorts in the kidnap scheme were quickly found and arrested, from the couple who owned the house where Urschel was held to gang members spending the ransom money. By September, the net had closed in on the Kellys, who were arrested in an early morning raid without a shot being fired. The pair was sentenced to life in prison the following month. Machine Gun Kelly died in prison in 1954, while Kathryn was released in 1958 and died in 1985.

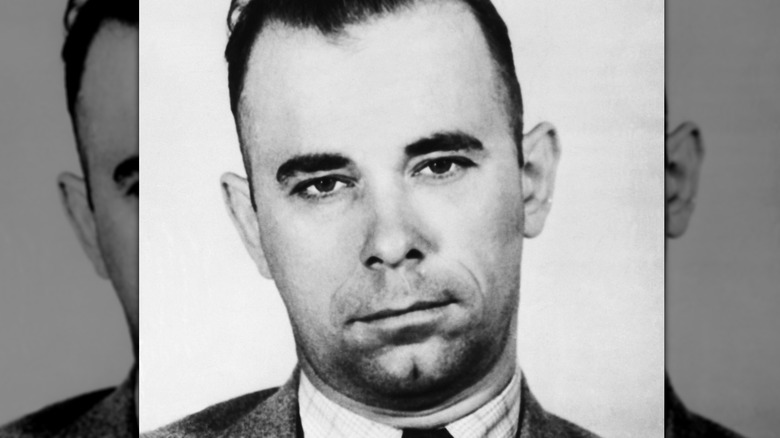

John Dillinger

J. Edgar Hoover was not the sole driving force behind the Bureau of Investigation and its campaign against Depression-era gangsters (one of the false things people believe about him). Melvin Purvis, hand-picked by Hoover to head the Chicago FBI office, was a key player in the downfall of three Public Enemies in 1934: Pretty Boy Floyd, Baby Face Nelson, and John Dillinger.

Purvis wrote in his autobiography, "American Agent": "There is probably no one whose career so graphically illustrates the inadequacies of our systems as does that of John Dillinger." Dillinger was in and out of trouble since his childhood, and after a nine-year prison sentence, he was paroled in 1933. Thus began an almost year-long spree of prison escapes, robberies, and killings as Dillinger and his gang wreaked havoc.

Though the general public loved Dillinger, his growing celebrity forced him to get plastic surgery in May 1934. He even tried — unsuccessfully — to get rid of his fingerprints before being named America's "Public Enemy Number One" in June. The next month, Special Agents Samuel A. Cowley and Melvin Purvis, acting on information from a friend of Dillinger's then girlfriend, fatally ambushed him outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago.

The Little Bohemia Raid

The fight against crime in Depression-era America was often an uphill battle for the FBI. For many years, it worked with one hand behind its back. Limited legal powers, qualified personnel, and weapons often gave criminals the edge, but the perfect storm of challenges for the lawmakers came in April 1934 with the Little Bohemia raid.

It should have been Melvin Purvis' finest hour: Capturing John Dillinger and his gang, including George "Baby Face" Nelson, at the Little Bohemia Lodge in Wisconsin. When the owners realized who they were, they hastily contacted Assistant Director Hugh Clegg, and a plan was hastily put into action. Unfortunately for Clegg, Purvis, and the other agents, it was chaotic and doomed. Unreliable vehicles, an isolated location in the snow, and darkness led to the team being split up — and the agents ended up targeting their own men.

The gunfire alerted Dillinger and his gang, who fired back before fleeing, while the agents kept shooting. As the criminals sought shelter with a couple before getting out of town, special agents Jay Newman and W. Carter Baum ran into George "Baby Face" Nelson. He shot them both, killing Baum, before disappearing into the night.

The Brady Gang

The death of John Dillinger in 1934 didn't put an end to the "Public Enemy" era — at least not in Alfred Brady's mind. He, Clarence Lee Shaffer Jr., and James Dalhover pledged to "make Dillinger look like a piker," per the FBI, and for several months between 1935 and April 1936, they fulfilled that vow. The trio were behind roughly 150 robberies and murdered between two and four people, depending on the source. Despite their long list of crimes, the newly named Federal Bureau of Investigation could not intervene as everything happened at a state level — until late April 1936. The Brady gang, having robbed an Ohio jewelry store, crossed the state line into Indiana with their ill-gotten gains, allowing the FBI to step in.

Brady and his men remained at large for several months, killing an Indiana state trooper in 1937, before escaping to Maine. They ended up in the backwater of Bangor, where, over multiple visits, they bought guns, including a deadly semi-automatic pistol. But when they asked for Tommy guns, the store owner told them to wait before quietly contacting the authorities, and FBI agents were able to position themselves around the town. When the Brady gang returned, a roughly four-minute gunfight erupted that left all three dead.

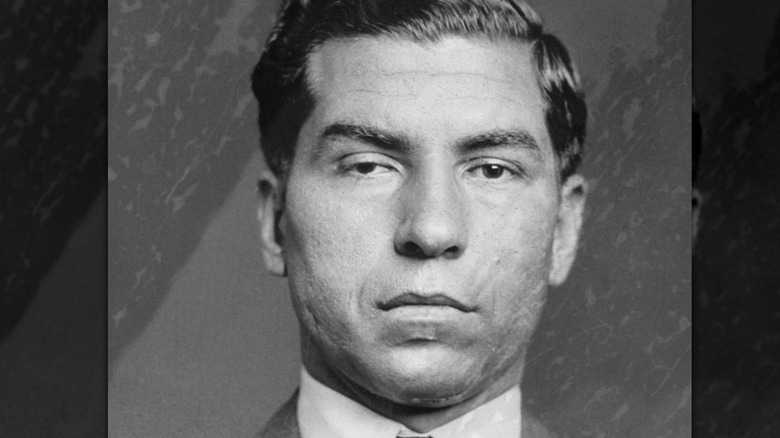

Charles Lucky Luciano

Salvatore Lucania came to the United States at 10 years old, launching his own protection racket shortly after. As a teenager, he changed his name to Charles Luciano, picking up the nickname "Lucky" in 1929 from life-long friend Meyer Lansky. Throughout the 1920s, he became the acknowledged head of a sophisticated network of organized crime he called "The Outfit" or "The Commission."

In the 1930s, Luciano also controlled a vast sex work ring. Although he focused on raking in profits for New York's Five Families and minimizing bloodshed, he was also attracting the attention of law enforcement officers. In 1936, New York special prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey named Luciano — who had fled the city for Ohio — Public Enemy Number One and launched a nationwide manhunt.

Luciano was eventually tracked down to Hot Springs, where he declined a request to return to New York, while state attorney general Carl E. Bailey was offered $50,000 to deny any extradition demand. Bailey refused, and Luciano was subsequently charged, tried, and convicted on more than 60 charges of compulsory prostitution. He served 10 years before being deported to Italy, where he died in 1962.