The Most Daring Rescue Mission Of The Vietnam War

From 1954 to 1975, North Vietnam (aka the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or DRV) and South Vietnam (aka the Republic of Vietnam) were locked in a brutal armed conflict. The root was the former's desire for a single unified communist regime after overthrowing the French government that had been in control for over half a century. (Here's the complete Vietnam War timeline, explained.) Other countries participated in the war as well, sending support to either side of the conflict: The DRV received assistance from China and the Soviet Union, while the U.S. fought alongside South Vietnam starting in 1965.

There is a sizable list of messed-up things about the Vietnam War, but there are also true accounts of breathtaking missions amid the combat that are equal parts educational, tragic, and inspiring. And chief among these, perhaps, is the story of the U.S. Air Force's desperate attempts to find and rescue its navigator, Lieutenant Colonel Iceal "Gene" Hambleton, in the thick of battle against North Vietnamese troops. It's a tale of multiple failed (and fatal) attempts to ascertain Hambleton's whereabouts and a last-ditch effort to save him with ground troops, grit, and golf references (it's also worth noting that this took place just a year before the U.S. withdrew all of its forces from Vietnam). These are the highlights of what has been called the U.S.'s "largest, longest, and most complex search-and-rescue operation" during the Vietnam War.

Who was Iceal Gene Hambleton (and why was rescuing him a top priority)?

To the uninitiated, it may seem like a baffling decision to spend so much time and resources to rescue just one military man in the thick of war, especially a 53-year-old pilot who'd been serving since World War II. Born in Rossville, Illinois, Iceal Hambleton was placed on active duty during the conflict between the Allies and the Axis powers but did not actually fight in the trenches. Half a decade later, in the Korean War, Hambleton put his talents and training to good use, flying a B-29 bomber and completing more than 40 missions.

After that, he spent the '60s working with missiles as part of the Jupiter medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) and Titan I and II intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) programs for the Army. Despite his age, Hambleton took on the responsibility of navigator during the Vietnam War, flying an EB-66 aircraft with the call sign Bat 21 Bravo. Fellow navigator Gerald Hanner, who wrote a book about EB-66 Destroyer pilots, observed that Hambleton likely accepted the assignment due to a desire to complete 30 years of service upon his retirement.

Hambleton had extensive experience — not just as a pilot, but also with ballistic missiles. This expertise, as well as his Top Secret clearance, was the main reason why it was imperative to rescue him. Had he fallen into the hands of Russian and North Vietnamese forces, the consequences would have been devastating for the U.S.

How Hambleton was placed in peril

On April 2, 1972, Iceal Hambleton and five other crew members were flying an EB-66, equipped for jamming electronic signals instead of actual fighting. This was Hambleton's 63rd combat mission. But tragedy struck when Hambleton and his crewmates were caught off-guard by North Vietnamese forces, reacting just five seconds too late to an incoming surface-to-air missile. At an altitude of over 30,000 feet, Hambleton, who was not commandeering the aircraft, speedily realized that he had no choice but to hit eject. Anticipating that at least his commander would follow suit, Hambleton was able to get out just before a second missile obliterated their vehicle — and he became the only person from the six-man crew to survive the attack.

Under normal circumstances, his parachute would have opened at 14,000 feet above ground. In an interview after his rescue, he revealed that this would have been a fatal move. "If I'd waited for the barometric opener [to open the chute at 14,000 feet], I'd have been out in the clear with 30,000 enemy troops around me, and I wouldn't be here today," he said, per Aviation Geek Club. Instead, he manually deployed his parachute after descending to below 28,000 feet, just in time for a dense mass of fog to provide him with enough cover to land without being targeted by enemy forces. "I got on the ground [in Vietnam] and found out what war was," Hambleton told the Syracuse Post-Standard in an interview sixteen years later (per the Los Angeles Times).

A valiant but doomed first rescue attempt

Landing on a rice paddy just south of the demilitarized zone between the two Vietnams, Iceal Hambleton began what would be a nearly two-week game of deadly hide-and-seek. The injuries he had sustained through this harrowing ordeal — which included a ripped finger, shrapnel embedded within his body, and a compressed spine that severely affected his mobility — meant that he was in immeasurable pain as he did his best to stay quiet and undetected. All the while, a massive contingent of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) was on the lookout for any troops that could have made it out of the shootdown alive.

Almost immediately, Hambleton's radio became an indispensable tool for him, allowing him to establish contact with the U.S. Army and making his eventual rescue possible. Unfortunately, the same environmental conditions that provided him the necessary cover to evade capture became the bane of the U.S.'s first efforts to retrieve him. It didn't take more than a few minutes after Hambleton's landing for the first rescue attempt: A UH-1H Iroquois helicopter with the call sign Blueghost 39, piloted by a four-man crew. Unfortunately, the team was unaware that the area — the Quang Tri province — was swarming with North Vietnamese soldiers. Enemy troops on the ground bombarded the helicopter with firepower, causing it to crash. Three of its crew members — pilots 1st Lt. Byron Kent Kulland, Warrant Officer John Wesley Frink, and crewchief Specialist Five Ronald Paschall — were slain, while gunner Specialist Five Jose Astorga was captured.

Desperate measures to keep Hambleton alive

Per Iceal Hambleton's own recollection, his descent took about a quarter-hour. The entire time, a U.S. forward air controller pilot was providing support via Hambleton's emergency radio. To help ensure Hambleton's survival, Colonel Cecil Muirhead, the U.S. Commander of Rescue Forces in Vietnam, decided that it was imperative to constantly monitor Hambleton's movements on the ground.

To accomplish this, Muirhead ordered round-the-clock forward air control coverage around Hambleton's known position, which required deploying six controllers who were alternating shifts every four hours. Captain Jimmie D. Kempton was one of these controllers, and he coordinated the subsequent (albeit ultimately failed) rescue attempts. In addition, Muirhead ordered Captains Rocky Smith and Richard Atchison, who were aboard one of the Army helicopters monitoring Hambleton, to set a standard 27-kilometer (16.8 miles) "no fire" zone around Hambleton's position to prevent him from being endangered by air or artillery fire.

Meanwhile, Hambleton was making his way through enemy lines with a barebones survival kit: in addition to his two URC-64 emergency radios, he also had a water bottle, a knife, flares, a first-aid kit, a small firearm, a compass, and a map. The radios fortunately turned out to be reliable, equipped with batteries with an estimated lifespan longer than the span of Hambleton's ordeal. By maintaining contact with the air controllers, they were able to track his movements and help him dodge the relentless enemy troops. As Hambleton himself admitted (per the U.S. Army War College), "Without that radio, I was dead!"

Subsequent rescue attempts from the air were unsucessful

For nearly a week, U.S. forces unsuccessfully tried to safely extract Iceal Hambleton from the battlefield. Meanwhile, the 24-hour forward air control monitoring directive put the controllers themselves at risk, and eventually, one of them, 1st Lt. Mark Clark, ended up needing rescuing as well. In 1972, in order to keep the North Vietnamese soldiers distracted and busy, the U.S. command in Saigon flew in B-52 bombers at high altitudes to drop bombs around the known locations of both Clark and Hambleton. According to HistoryNet, it's been estimated that "hundreds" of these air strikes were conducted.

Four days after Hambleton's unplanned descent, U.S. command ordered 42 air strikes around him and determined that it was time to send in a rescue helicopter. HH-53 helicopter Jolly Green 67 — manned by pilot Captain Peter H. Chapman, co-pilot Captain John H. Call, pararescuemen Technical Sergeant Allen J. Avery and Technical Sergeant Roy D. Prater, flight engineer Sergeant William R. Pearson, and combat cameraman Sergeant James H. Alley — swooped in amid the deafening silence. But they were taken by surprise by undetected North Vietnamese ground troops. The helicopter went down, and none of the crew survived. On April 7, another support helicopter went down, crashing near Blueghost 39's wreckage. As the days passed, each unsuccessful rescue attempt just added more names to the lists of captured and deceased U.S. airmen. (Read why the Vietnam War was worse than you thought.)

Operation Bright Light: A ground rescue operation with a not-so-bright record

On April 9, General Creighton Abrams, the overall commander of the U.S. forces during the Vietnam War, took a look at the losses incurred by the U.S. in its efforts to rescue Iceal Hambleton. There were 14 casualties, two airmen captured, two missing, and eight destroyed aircraft, and Abrams determined that it was time to change tactics. He immediately put a stop to further helicopter rescue attempts, and the surviving airmen were withdrawn from the area. According to reports, it was Marine Lieutenant Colonel Andy Anderson who came up with an alternative search-and-rescue solution: Operation Bright Light, a less costly, ground-based mission that utilized highly specialized Navy SEALs. (Here's why SEAL Team Six is one of the world's most elite kill teams.)

It's important to note, though, that at this point, Operation Bright Light didn't exactly have the brightest track record. In fact, at that point, it had been established for six years, yet still had no successful American prisoner-of-war (POW) rescues under its belt. Nevertheless, Bright Light was carried out as a preventive measure to avoid the possibility of Hambleton becoming a POW in the first place. Leadership responsibility was placed upon the shoulders of U.S. Navy SEAL Lieutenant Thomas R. Norris. Joining him on the small makeshift team were ARVN Petty Officer Nguyen Van Kiet and four other Lien Doc Nguoi Nhia ("soldiers who fight under the sea"), the South Vietnamese counterparts of the Navy SEALs. Their mission: Rendezvous with Hambleton and Mark Clark, who were separately radioed instructions to help them make it safely to a nearby riverbank.

Rescuing Mark Clark — and finding Hambleton

The next day, the ground rescue team was swiftly deployed in a bunker near the Song Mieu Giang river — they had been ordered to prioritize the rescue of Mark Clark, moving in the dark of night. Adding an extra layer of challenge to this difficult mission was the fact that Lt. Thomas Norris' team was not in direct contact with their two targets — the safer option, no doubt, because the North Vietnamese troops who could listen in on their radio communications understood English. As such, the radio operators resorted to creative ways of stating their instructions to the two imperiled airmen.

Instead of being directly told to swim and look for Norris' team along the river, Clark, an Idaho native, received this strange instruction (via HistoryNet): "When the moon goes over the mountains, become Esther Williams and get in the Snake and go from Boise to Twin Falls." Williams, a swimmer and actress, starred in the 1950 film "Duchess of Idaho," while Boise and Twin Falls are cities in Idaho. Unfortunately, Norris' initial attempt to retrieve Clark failed — his team saw Clark floating by but had to let him pass because enemy troops were nearby. After the danger passed, the ground rescue team attempted to track down Clark once more, and after a few hours of searching, they found him. They almost didn't make it because North Vietnamese troops found the bunker and rained fire on them, but Anderson called in a few air strikes, distracting the enemy and providing the team with enough time and cover to get out of the area alive.

Rescuing Iceal Hambleton, made possible by ... golf?

Coordinating Iceal Hambleton's rescue was a slightly more complicated matter, as he was farther from the river than Mark Clark. But as it turned out, the key to his salvation was a hobby that he was known to excel at: golf. In fact, Hambleton reportedly had a "vivid memory" of specific golf courses, which the rescuers used to their advantage.

Some of the instructions Hambleton received included playing 18 holes and starting at "No. 1 at Tucson National." Per a 2001 Golf Digest interview, because Hambleton remembered that Tucson National "is 408 yards running southeast," he was able to correctly decipher that the rescuers were telling him to run in the direction of the river. By interpreting subsequent mentions of golf course holes as precise instructions for the distance and direction he should be moving, Hambleton survived his dangerous imaginary golf game while dodging enemies along the way.

There was just one instance in which, driven by hunger, Hambleton tried to capture a rooster, only to be attacked by an assailant hiding in the dark. Hambleton killed his opponent, but not before getting his left shoulder slashed. By the time he met with Lt. Thomas Norris and LDNN Petty Officer Nguyen Van Kiet (who were disguised as fishers) on April 13, he was nursing, in addition to his previous injuries, a broken wrist. He was also in a semi-delirious state, having lost a staggering 45 pounds and suffering from food poisoning due to drinking contaminated water.

Rescued — but at what cost?

While Iceal Hambleton succeeded in meeting up with his rescuers, it took a while before they were finally in the clear. While making the dangerous trek to safety, they encountered North Vietnamese soldiers not once, but twice. While they managed to evade their potential attackers the first time, the second time almost took a tragic turn, as they found themselves staring down the business end of a heavy machine gun. Fortunately, aid came in the form of seven bombers from the USS Hancock, who swiftly came to the scene after Lt. Thomas Norris called for help. The air strikes took out a few enemy troops, with the resulting chaos allowing Norris and LDNN officer Nguyen Van Kiet to bring Hambleton safely back to base.

Aside from the aforementioned American casualties and destroyed aircraft, many members of the various rescue teams sustained injuries over the course of the nearly two-week operation to rescue Hambleton. The U.S. military also ordered over 800 air strikes to aid the rescue efforts. In addition, it cannot be discounted that, due to the "no fire" zone established within the radius of Hambleton's estimated location, there is a possibility that South Vietnamese soldiers could have died there as well. While Hambleton was grateful to have been rescued, he also openly lamented the heavy setbacks incurred by the U.S. during the rescue efforts and was even deeply apologetic about the way things unfolded, despite being out of his control. "It was a hell of a price to pay for one life," he told the Associated Press after his safe return (per the Los Angeles Times).

After the rescue

After he and his team successfully brought back both Mark Clark and Iceal Hambleton, Lt. Thomas Norris received recognition from the U.S. government in the form of the Medal of Honor, the highest award given for valor in military service. Reportedly, Norris initially rejected this, perhaps connected to his team's failure to rescue a third U.S. military man, 1st Lt. Bruce Walker. However, Norris ultimately accepted the award in 1975. Meanwhile, for his role in the rescue mission, DNN officer Nguyen Van Kiet was awarded the U.S. Navy Cross, the second-highest award for U.S. military heroism, in 1976. Only one other Vietnamese serviceman shares the distinction of receiving this award.

The successful outcome of the attempts to rescue Hambleton did not blind the U.S. military to the fact that their procedures and protocols needed heavy adjusting to minimize casualties and expenses. It reevaluated its standard operating procedures (including the prerequisites for launching a search-and-rescue operation) and updated its technology and training to avoid sending future rescuers to their own deaths. As for Hambleton, he received the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, the Meritorious Service Medal, and the Purple Heart for his service during the Vietnam War. Speaking to the Los Angeles Times, Hambleton's sister-in-law, Donna Cutsinger, said the airman had a lot of speaking engagements in which he shared the story of his daring rescue and enjoyed a quiet retirement in Arizona for the next three decades of his life while playing "a lot of golf." He passed away at a hospital in Tucson on September 19, 2004, from pneumonia connected to lung cancer.

The story of Hambleton's rescue, immortalized

The daring account of Iceal Hambleton's successful rescue from behind enemy lines proved to be an interesting story for many, as evidenced by the number of times the subject has been covered by literature and even a full-length feature film. The first to provide a deeper examination of what Hambleton's life was like as a soldier in the Vietnam War was a 1980 book titled "Bat-21," penned by Lieutenant Colonel William Charles Anderson. This creative work was reportedly written with some fictional twists and omissions, such as the total absence of any mention of Thomas Norris, Nguyen, or their ground team, due to the classified status of the mission at the time Anderson was writing the book.

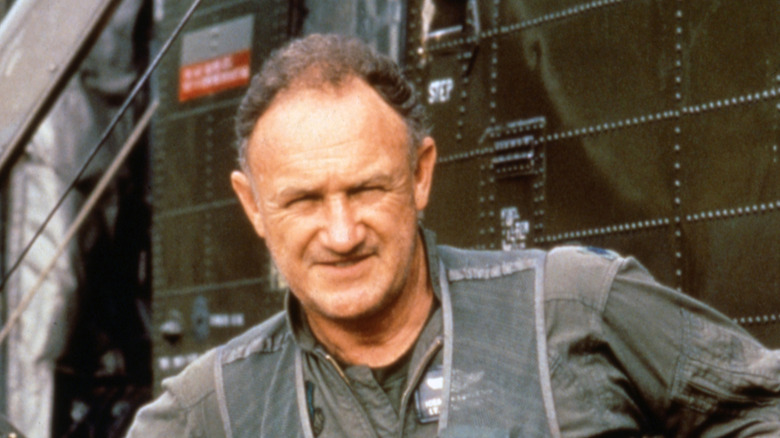

The work became the basis of the 1988 film of the same name, which featured Gene Hackman as Hambleton alongside Danny Glover as flight controller Captain Bartholomew Clark, a made-up character meant as a stand-in for the numerous military men involved in Hambleton's rescue. A decade after the film's release, Colonel Darrel D. Whitcomb, who had also served in Vietnam, published his account of the events in a book called "The Rescue of Bat 21." As the rescue mission was declassified sometime during the 1980s, "The Rescue of Bat 21" told Hambleton's story in greater and more accurate detail. (Read about the most bizarre unsolved mysteries of the Vietnam War.)