The Biggest Cold Cases Finally Solved With DNA In The Last Decade

For centuries, to solve a crime, investigators had to rely on the testimony of witnesses (presuming there were any), physical clues, and deduction. A revolution occurred in the 1890s, when fingerprints on a door frame helped identify a killer in Argentina. Within a few years, the technology was being used across the world to bring criminals to justice — but it was just the start of the role of science in crime detection.

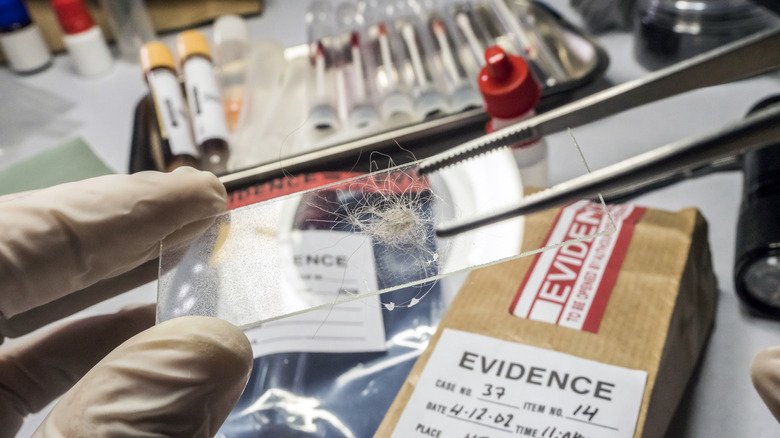

The 1980s heralded the dawn of the DNA age. Skin, hair, blood, and other physical evidence left at a crime scene could be analyzed to identify who left these vital traces. DNA technology was first used in England in 1986 to convict murderer Colin Pitchfork, but has evolved extensively since then, becoming more sophisticated and accurate. It's hoped that DNA analysis will finally solve the decades-old killing of JonBenét Ramsey, but it's not always an exact science.

In his 2014 book, "Naming Jack the Ripper," author Russell Edwards claimed DNA on a shawl, found at the site of Catherine Eddowes' death, identified Polish barber Aaron Kosminski as the murderer. Edwards repeated his assertion in 2025, despite skepticism from many quarters. Although it remains to be seen whether the Ramsey or Ripper cases will ever be cracked using DNA, there are many cold cases that have been solved — some more recently than you might think.

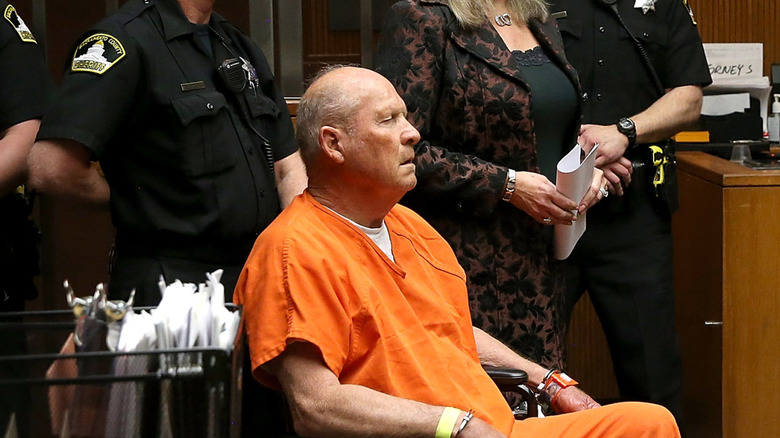

US: The Golden State Killer

It is a fundamental right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty, and someone should only be investigated if there is a reasonable suspicion they have broken the law. Balancing an individual's rights to privacy with the duty to protect the public can be a delicate line to walk for law enforcers. Catching the Golden State Killer, a burglar, rapist, and murderer, who terrorized Californian residents during the 1970s and '80s, would test these principles like never before.

Initially, detectives investigating the crimes believed more than one person was responsible, but they struggled to find any suspects. DNA samples were recovered from the crime scenes, but none found a match in the National DNA Index System. In 1986, the Golden State Killer's spree seemingly ended with the murder of 18-year-old Janelle Cruz, and the case went cold for 40 years, until police took a radical step in 2018. They uploaded their DNA samples to the genealogy site GEDmatch. It included data from websites including Ancestry and 23andMe, and had been used by relatives of the Golden State Killer.

Detectives built up a family tree of their suspect, using what expert CeCe Moore described as "reverse genealogy" (via Forbes) that focused on third cousins. By studying the male and female genetic intersections, they could pinpoint anyone who shared the suspect's physical traits. Eventually, the finger of suspicion pointed to Joseph James DeAngelo. Fresh DNA samples (taken covertly) were compared to the crime scene evidence. In April 2018, the 72-year-old former police officer was finally arrested.

Australia: Somerton Man

Just as all that glitters isn't gold, sometimes a mystery isn't quite as, well, mysterious, as it first appears. Somerton Man, one of Australia's longest and most enigmatic cold cases, is a perfect example. It began on December 1, 1948, when the body of an unidentified man was found on Adelaide's Somerton Beach. Alongside his physical appearance, more intriguing details were noted, including train and bus tickets, missing labels on his clothing, and a scrap of paper in a hidden pocket with the words "tamám shud" written on it. A plaster cast of his head and shoulders was taken, and a worldwide race was on to identify the Somerton Man.

Many theories circulated over the years, from his being a Russian spy to being related to ballet dancer Robin Thomson, but none of them led anywhere. In May 2021, his remains were exhumed at the request of University of Adelaide professor Derek Abbott, the husband of Thomson's daughter Rachel, so forensic tests could be carried out to determine whether Somerton Man was her grandfather. He wasn't.

The answer lay in several strands of hair, caught in the plaster cast, that were given to Abbott by the police years earlier. He partnered with American genealogist Colleen Fitzpatrick to create a 4,000-member family tree using DNA from the hair, which led to a first maternal cousin, three times removed. So, who was Somerton Man? According to DNA, he was Melbourne-born electrical engineer and poetry fan, Carl "Charles" Webb. Australian authorities have yet to confirm Abbott's conclusion.

Canada: Sharron Prior

There are many cases where, despite the best efforts of detectives, criminals are never brought to justice. Although it is devastating for the relatives of victims, occasionally, time doesn't just heal, it allows technology to advance far enough to ensure justice is done. Such was the case for the family of 16-year-old Sharron Prior from Montreal, whose body was found in the woods three days after she went missing in 1975.

At the time, the amount of DNA and forensic material gathered from the crime scene, including a shirt that was used to bind Sharron, wasn't enough either to be tested or presented as evidence in court. Although over 100 suspects were investigated, the perpetrator remained unknown, and the trail went cold. In a million other cases, the slender evidence would be shuffled around or lost over the years. Not this time.

Leaps in DNA technology enabled scientists to take a "boosted" sample from the saved evidence, and in 2019, they were sent to a West Virginia lab where, similar to the Golden State Killer case, genetic genealogy was used to compare the DNA to thousands of people. By analyzing the paternal Y chromosome, the trail led to the Romine family, whose son Franklin was already known to the police. Although he died in 1982, his body was exhumed, and DNA from it matched samples from the Prior case. In 2023, investigators solved the case, saying they could, "with 100% certainty," (via Facebook) conclude that Romine was her killer.

US: Marise Chiverella

For years, amateur sleuths could only read about Sherlock Holmes' or Miss Marple's investigations, but the internet changed all that. It allowed amateur sleuths to get involved in cases, swap theories about suspects, and — in very rare instances — actually solve them. That's what happened to 20-year-old college student Eric Schubert, after he helped close a murder case that had been cold for almost 60 years.

When 9-year-old Marise Chiverella was found murdered hours after setting off for school in 1964, the local police in her hometown of Hazleton, Pennsylvania, were desperate to find her killer. Unfortunately, the investigation went nowhere, and the case was handed down through the years. Things started to change in 2007, when a DNA profile was created from forensic evidence on Chiverella's clothing. Eleven years later, technology and genetic genealogy firm Parabon NanoLabs became involved and shared the DNA data with GEDmatch, where they unearthed a very distant cousin.

Here's where Elizabethtown College history student Eric Schubert came in. He had helped in other cases and offered to do the legwork in the Chiverella murder by using DNA samples to assemble a family tree. The trail eventually led to James Paul Forte, a known criminal with no connections to Chiverella or her family, who had died in 1980. His body was exhumed, and a DNA sample matched the traces on Chiverella's jacket. "That's the thing about genetic genealogy. The evidence is in the DNA," Schubert told CBC.

Canada: Babes in the Woods

DNA and forensic technology have come on in leaps and bounds since it was first used to secure Colin Pitchfork's murder conviction in the United Kingdom in January 1988. As good and reliable as it has become, sometimes it can only provide half the story. In 2022, for Vancouver police, DNA helped with a crime that had been unsolved for 70 years. Known as the "Babes in the Woods" case, it involved two young boys, whose remains were found in the city's Stanley Park in 1953, though they had died long before then.

For almost 40 years, officials believed the bones were of a boy and a girl, but dental DNA extracted in 1997 revealed they were half brothers. But who were they? In 2015, a former Vancouver detective suggested a local woman could be their mother, but attempts to recover mitochondrial DNA from the bones proved inconclusive. However, thanks to evolutions in technology, that changed in 2021.

Vancouver police worked with Redgrave Research to extract DNA from teeth and skull fragments from both boys. The initial samples were too small, but a larger piece of bone from the older boy proved to be enough to sequence his DNA. After comparing it to information on genetic databases, researchers tracked down the boys' living relatives and eventually identified the children as 6-year-old David D'Alton and his 7-year-old half-brother Derek. Sadly, their killer has never been found.

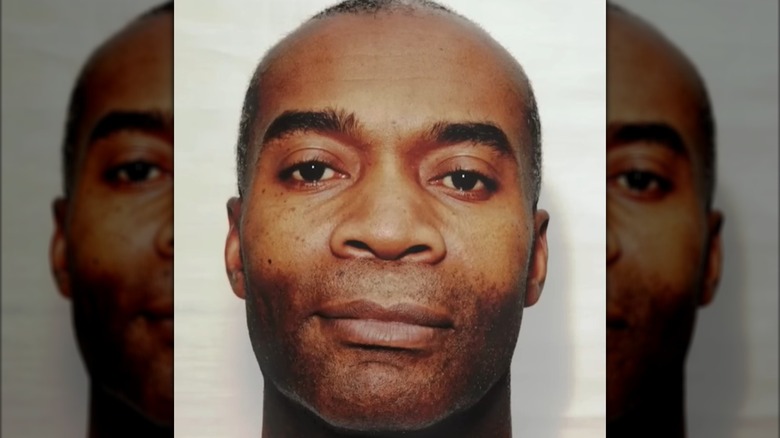

UK: Delroy Grant, The Night Stalker

The Yorkshire Ripper case in the United Kingdom stands as an infamous example of how a botched investigation can allow a criminal to slip through the net. But it wasn't the only time police in the U.K. messed up. What the press dubbed a nearly 20-year "reign of terror" by a man known in England as "The Night Stalker" (not to be confused with American serial killer Richard Ramirez) could have ended in half the time, had DNA profiling not sent detectives on a wild goose chase.

Between 1991 and 2009, more than 200 elderly women in southeast London, aged between 68 and 89, were attacked in their homes, and detectives used the latest in DNA profiling to catch the culprit. A search of the national database turned up no results, so, desperate police turned to a Florida-based company for a profile. It suggested the prime suspect had ancestors from the Windward Islands, but while detectives scoured the Caribbean, back in London, the attacks continued.

Matters were made worse by the wide net cast by officers. More than 3,000 DNA samples were taken and the list of people of interest ran to 21,000 names. One of them, Delroy Grant, was eliminated as a suspect in 1999 due to a case of mistaken identity. A decade later, a vast surveillance operation was launched in a change of tack — and it worked. Grant's car was pulled over, and his DNA, including that found on a carton of juice in a victim's home, connected him to 11 of the Night Stalker's victims.

US: Bear Brook Murders

Many criminals change their names to avoid detection, but their DNA will never lie. Terry Rasmussen went by so many aliases that he was dubbed "The Chameleon Killer." It's uncertain how many murders he actually committed before his 15-year-to-life conviction in 2003, but DNA did help connect Rasmussen with what became known as the Bear Brook Murders. In 1985, a barrel containing the remains of a woman and a child was discovered close to Allenstown's Bear Brook State Park. Fifteen years later, a second barrel, with the remains of two more children inside, was found close by.

It took until 2019 for them to be identified, after genetic genealogist Barbara Rae-Venter used the then-revolutionary technique of extracting DNA from a hair sample. It allowed detectives to not only name three of the victims: Children Marie Vaughn and Sarah McWaters and their mom, Marlyse Honeychurch, but also their killer: Terry Rasmussen. But what about the fourth body, Jane Doe 2000, who came to be known as "The Middle Child"?

As forensic science advanced, so experts continued to try to identify the girl. In 2016, DNA revealed she was Rasmussen's biological daughter, but it took until 2024 to find the woman who genetic genealogists believed was her mother. A birth record confirmed Rasmussen and Pepper Reed were the girl's parents, while a DNA sample from the latter's brother proved the familial link. In September 2025, "The Middle Child" was formally identified as Rea Rasmussen, almost 15 years after her father died in prison.

US: The Boy in the Box

Emotions ran high for 65 years when the body of a young boy was found in a bassinet box in Philadelphia in 1957, both in the city and nationwide. At the time, police exhausted every forensic avenue to try to find out who the child was, from trying to match footprints from the scene to taking a cast of his face.

By 1998, DNA technology was in its infancy, but officials thought it could produce a lead. The boy was exhumed and samples were taken, but no results came up on the Combined DNA Index System. Ten years later, Philadelphia detectives launched a program using cutting edge genetic genealogy to identify several individuals — including the so-called "Boy in the Box." A second exhumation in 2019 extracted more DNA for testing, but it took more than two years to generate a suitable sample. That's when the case finally turned a corner.

Colleen Fitzpatrick, Misty Gillis, and Identifinders International used the DNA to build a family tree that led to a potential candidate for the boy's mother. A birth certificate also listed the boy's possible father and after contacting relatives were able to finally give the Boy in the Box a name: Joseph Augustus Zarelli. Although his grave now bears his name, the investigation into who killed him remained active as of 2025.

US: The Grim Sleeper

Bernie Madoff, who ran the world's largest Ponzi scheme, was famously turned in by his sons after he confessed his activities to them. But what about violent criminals who are brought to justice by their relatives without either side's knowledge? In 2010, new technology called familial DNA was used to catch The Grim Sleeper, ending a serial killer's spree that lasted more than 20 years. At a press conference, Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck said the method would "change the way policing is done in the United States," per ABC News.

Ethical questions about familial DNA swirled almost immediately, but there was no doubting its efficacy. Initially launched in November 2008 by Attorney General Edmund G. Brown Jr., California's familial search program contained DNA data that could be compared with that from crime scenes and identify family members of potential suspects. Detectives hunting The Grim Sleeper used the program the year it began operating, with no success. However, in April 2010, a partial match surfaced.

Between 2008 and 2010, the son of Lonnie David Franklin — later revealed as The Grim Sleeper — had been arrested and his DNA uploaded to the database. Some of his unique DNA markers also appeared in the crime scene samples, suggesting the two individuals were related. Detectives combined the data with other information and, after testing Franklin, finally had their man. Although the Supreme Court has validated the use of familial DNA, privacy and civil liberties groups warned it could be harmful to minorities.

US: Lady of the Dunes

Millions of people across the world have fleshed out their family trees using sites like 23AndMe or Ancestry. While some want to uncover connections to a famous (or infamous) person, Richard Hanchett just wanted to find his birth mom. He would get his wish, but little did he realize she was at the center of one of Massachusetts' oldest cold cases. The "Lady of the Dunes" had been found dead in the sands near Provincetown in 1974, and for years, attempts to identify her drew a blank.

Detectives tried everything, including facial reconstructions and artificially aged images, all to no avail. Then, in 2018, Hanchett submitted a DNA test to Ancestry, which led to a meeting with biological relatives in Tennessee. They told him about his mother, Ruth Marie Terry, but more was to come. Four years later, detectives asked Hanchett for DNA to compare to a sample of the unnamed victim's jaw that was being tested by experts at a forensics laboratory. The results produced a match, confirming the "Lady of the Dunes" was his mom.

In the years since she was found, theories about her killer included infamous gangster James (Whitey) Bulger, or that she was an extra from the hit movie "Jaws." The truth, detectives later revealed, was even sadder. They strongly suspected Terry was killed by her then-husband, Guy Rockwell Muldavin, just a few weeks after they married. He died in 2002.

UK: Ryland Headley

In every crime drama involving a cold case, there's always a dogged investigator willing to go the extra mile when everyone else has given up. When it came to finding out who killed 75-year-old Louisa Dunne in 1967, that dogged investigator was Jo Smith. She didn't just have to read through a few files; she had to sort out and bag all the forensic evidence linked to the case before she even got started.

The investigation kicked into a new gear in late 2023 when forensic evidence was sent off for analysis, and unlike in the movies, it took months for the results to come back. But when they did, Simpson was amazed. The materials had included Louisa Dunne's skirt, and forensic evidence traces had yielded a full DNA profile of her attacker, thanks to revolutionary DNA-17 profiling. This technology was able to assess more short tandem repeat loci than previous iterations, enabling a profile to be extracted even from low-quality DNA samples.

Even more shocking, decades after Dunne's murder, the perpetrator was still alive. In November 2024, 92-year-old Ryland Headley was arrested after his DNA, taken in 1977 for two separate crimes, matched that found on Dunne's clothing. In addition, a partial palm print, found on a window inside her house, also matched Headley. In court, the jury was told "the DNA was a billion to one times more likely to be from Headley," via Avon and Somerset Police. He was sentenced to life, with a minimum term of 20 years.