Times Alcohol Changed The Course Of American History

Despite being a relatively "young" country, the United States of America has a long and storied history that goes back centuries. As a former British colony, America was founded with a spirit of rebellion and self-determination, not to mention that well-documented commitment to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

And also? America was founded with the help of lots and lots of booze. So, so much booze.

It's true! Without alcohol, the country would look very, very different. Thanksgiving may never have happened. George Washington probably wouldn't have been elected as our first president. Abraham Lincoln might've finished his second term in office, and the Vietnam War probably would've gone nuclear.

Seriously. It doesn't matter which beverage you prefer. Beer, whiskey, rum, cider, and more all had a major impact on the future of America, and therefore, the world. Still don't believe us? Here are just a few examples.

The Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock to make a beer run

The Mayflower encountered many hardships en route to the New World, but only one ended their journey: As they approached their destination, the ship's beer supply was running low. This was a problem, because the Mayflower's crew wasn't going to settle in America alongside the Pilgrims they were transporting, and the sailors needed to save some beer for their voyage home.

See, during long sea voyages, water tends to go bad fairly quickly. Fermented beverages like beer, however, last for months, making them ideal for keeping both crew and passengers hydrated. Naturally, the concoction served on the Mayflower was much lower in alcohol content than modern beer — all passengers, including children, drank up to a quart a day.

And so, instead of traveling south to more hospitable farmland, Mayflower captain Christopher Jones parked his ship for the winter and forced the Pilgrims to disembark at Plymouth Rock, forever changing the course of history. The settlers, Jones figured, could drink water once on land, letting the crew preserve enough beer to last them through their spring voyage. The plan worked, although the Pilgrims weren't too happy about it. After the Mayflower's passengers disembarked, they complained about the water in New England, and said they'd much rather be drinking beer instead. Still, Jones held fast, although he did surprise the settlers with some extra brew on Christmas Day.

So, while you're scarfing down your turkey and mashed potatoes next November, make sure you save room for a pint or two. Without beer, Thanksgiving never would've happened.

The Boston Tea Party was really about a different drink

Sure, the British love their tea, but you know what the American colonists were actually into? Rum. Not only was rum the most popular beverage in the New World, but it accounted for about 80 percent of New England's exports, and was a pivotal part of the West African slave trade, which largely kept the colonies going.

So, of course, the British were none too pleased that Americans preferred to make their rum using molasses imported from France, not other English colonies, and began levying taxes to try to make the settlers change their ways. The Molasses Act of 1733 imposed harsh penalties on French imports. But it wasn't enforced, and it changed nothing. The Sugar Act of 1764, on the other hand, caused a major uproar. Protests against the Sugar Act spawned the phrase "No taxation without representation," which became the American revolution's rallying cry, and bolstered support for the secession movement.

Britain later imposed other duties, including the tea tax that inspired a bunch of patriots to storm a ship in Boston Harbor and toss its contents overboard, but by that point the colonists were really taking out decades' worth of frustration. Years after the American Revolution, founding father John Adams admitted it was molasses — and, by extension, rum — that got the whole thing going. And why not? "Many great events have proceeded from much smaller causes," he said.

Without alcohol, George Washington probably wouldn't have been our first president

You know what's a great way to win an election? Get potential voters good and drunk before they head to the ballot box. This practice, known as "swilling the planters with bumbo," was a common procedure during the days of early American history, and helped swing more than one election. That's something that George Washington learned the hard way: In 1755, Washington campaigned against drunkenness while running for the Colony of Virginia's main legislative body and lost very badly. The next time he ran, he gave each individual voter half a gallon of booze. Naturally, he won.

Later, while leading the Continental Army against British forces, Washington came out in favor of drinking among members of the military, arguing that alcohol boosted troops' morale, helped relieve the tedium of long marches and uncomfortable conditions on the battlefield, and gave them just a smidge of much-needed liquid courage. Still, Washington wasn't always a friend to America's drunks. When it came time to repay some of the debts incurred by the American Revolution, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and now-President Washington began to tax whiskey, which had supplanted rum as the country's drink of choice.

Farmers and distillers, who relied on whiskey to make a profit on America's swelling stockpiles of corn, wheat, and rye, fought back. They refused to pay the fees. Whenever a tax collector showed his face, they tarred and feathered him. By the time the farmers began burning down tax officials' houses, Washington was forced to respond by sending in a militia 13,000-men strong to put the so-called Whiskey Rebellion down. Ironically, after he retired, Washington actually opened his own distillery — and by the time he died in 1799, it was one of the biggest in the country.

The fruits of Johnny Appleseed's labors were used for booze, not snacks

In the early 1800s, John Coleman wormed his way into American folklore by embarking on a very unusual mission. Armed with a sack full of apple seeds, Coleman trekked across the American west, planting trees wherever he went. Over time, he earned the nickname Johnny Appleseed.

That's all well and good, but there are a few details that the common version of the story leaves out. For one, Coleman wasn't just planting fruit out of the goodness of his own heart, although he was a vocal conservationist and had a strong compassionate streak. In some versions of Coleman's story, he was a businessman who was helping to establish nurseries in order to flip them to oncoming settlers, all of whom were required to plant orchards in order to secure their land. In others, his interest in apples came from the Bible, and he used their symbolic significance as a tool to spread the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, who established the branch of Christianity known as the New Church.

More importantly, the apples that Coleman's trees produced weren't used for eating. They were used to make cider. Apple trees grown from seeds tend to produce fruit that's sour and unpleasant — the apples you know and love today are created through a process known as grafting — but they're excellent for brewing. In fact, among early American frontiersmen, cider was a very popular beverage. Like beer, it's easier to store than water, it doesn't taste that bad, and has a little kick. No wonder Coleman was so popular: In addition to everything else, he was bringing alcohol to the masses.

Lincoln's bodyguard was out drinking while the President was assassinated

You probably know what happened at Ford's Theater on April 14, 1865, but just in case, here's a quick reminder: President Abraham Lincoln and his guests were there to see a performance of Our American Cousin. During the show, a guy named John Wilkes Booth snuck into the presidential box and shot Lincoln in the back of the head. Lincoln died the next day.

Maybe things would've gone differently, however, if John Frederick Parker, a Washington DC police officer, had done his job correctly. Not that anyone should've expected much from Parker, of course. Before landing the presidential protection gig, Parker had been disciplined a number of times, including for being drunk on duty and for taking a nap on a passing streetcar during his shift. On that fateful April night, however, he was the sole person in charge of Lincoln's safety — remember, the Secret Service wouldn't be founded until a few months later, and focused primarily on hunting down counterfeit currency until 1901. Obviously, Parker blew it — here's how.

First, Parker arrived three hours late for his shift. Next, after Lincoln took his seat, Parker abandoned his post to get a better view of the stage. Finally, during intermission, Parker left Ford's Theater entirely and joined a few members of Lincoln's support staff at the bar next door, clearing the way for Booth's deadly attack. Remarkably, even that oversight didn't end Parker's career: Shortly afterwards, he was assigned to protect the White House, much to the grieving Mary Lincoln's displeasure.

During Prohibition, alcohol defined an entire decade

Ironically, alcohol's most dramatic effect on American history came when people tried to get rid of it. While the temperance movement had been growing since the end of the Civil War, it wasn't until January, 1920, when the 18th Amendment came into effect, that alcohol became entirely illegal. Those in favor of prohibition argued that banning alcohol would cut down on crime and increase sobriety while boosting the economy by freeing up resources. That'd give people more money to spend on other goods and services, and increase productivity.

Of course, things didn't quite work out that way. Yes, overall alcohol consumption fell during Prohibition, as did public drunkenness and booze-related health disorders. However, the closing of major breweries and distilleries led to a sharp rise in unemployment. Restaurants and theaters went out of business, damaging the entertainment and hospitality industries. The government lost $11 billion in tax revenue from the alcohol sales that they were no longer taxing, on top of the $300 million it spent trying to keep Americans sober.

And then, there's the crime. While some evidence suggests that overall violent crime rates fell during Prohibition, bootleggers and smugglers stepped into the void legitimate brewers could no longer fill, building vast criminal empires while increasing corruption in civil institutions like city police forces. By the time that Prohibition ended in 1933, America's criminal underworld had undergone a massive transformation — and we all have Prohibition to thank.

Nixon's drinking almost started — and then saved us from — nuclear wars

Richard Milhous Nixon was many things, including a heavy drinker. In fact, he once asked an 11-year-old Jet Li to be his bodyguard when he grew up (Li said no). Even before the Watergate scandal ruined both Nixon's reputation and his political career, the 37th president of the United States would have one, or two, or a few too many in the evenings. Even worse, when he was drunk and angry, he'd order his subordinates to launch nuclear strikes.

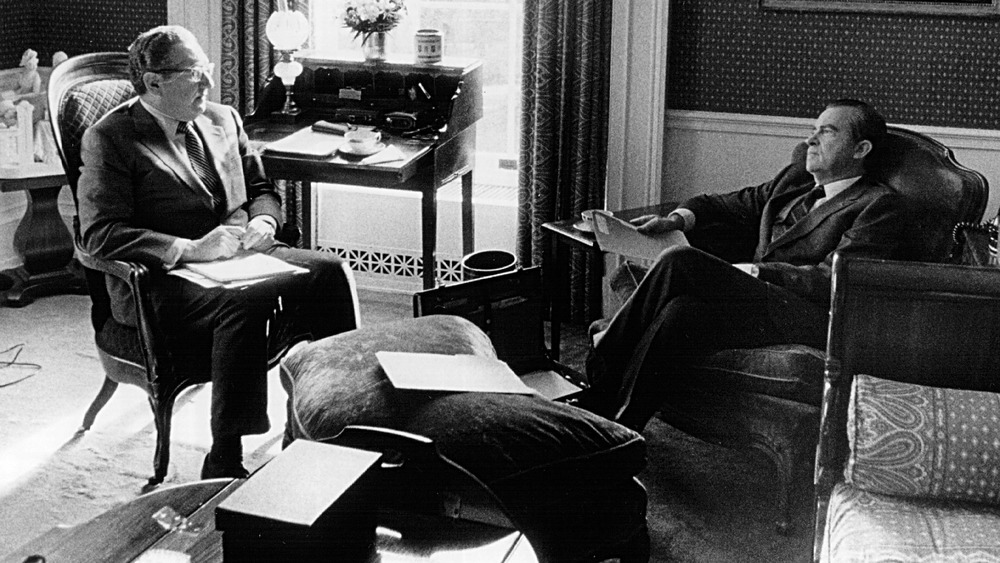

It happened once in 1969, when North Korea shot down an American spy plane, and Nixon decided to nuke North Korea in response. It happened again during a particularly heated conversation about Cambodia, which Nixon invaded in a major escalation of the Vietnam War. While drinking, he often talked about dropping nuclear bombs on Vietnam. In fact, Nixon's Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, is quoted as saying, "If the president had his way, there would be a nuclear war each week!"

The one thing that saved, well, everyone? Ironically, also Nixon's drinking. Whenever the drunk president ordered something like a nuclear strike, Kissinger would tell the rest of the administration to wait until the morning, after Nixon had sobered up. When dawn came, Nixon would continue on as if nothing had happened the night before, probably because he simply didn't remember ordering the nukes — until, of course, the whole situation came up again.