The First Person To Successfully Use The Temporary Insanity Defense

The first successful use of a plea of not guilty by reason of temporary insanity was a mess. The lawyers barely established that their client had actually acted in an insane manner, and they tried to assert temporary insanity while simultaneously hammering away at the justification that their client had sought to regain his honor.

In the end, the public turned on Daniel Sickles more when he took his wife back than when he'd killed his wife's lover. But despite everything, Sickles went on to be remembered for his Civil War escapades instead of the murder he committed. Meanwhile, the legacy of the temporary insanity defense persisted for another century until legislation in the 1980s shifted the burden of proof. And although the temporary insanity plea wasn't always used successfully, Sickles' defense set the stage, especially for spouses who murdered their partners' lovers. This is the story of the first person to successfully use the temporary insanity defense.

Rex v. Arnold

In 1724, Edward Arnold attempted to murder Lord Onslow in England. The resulting case, Rex v. Arnold, ended up becoming the first in which a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity was accepted and given a definition.

Law Explorer writes that while the defense admitted that Arnold had shot and wounded Lord Onslow, they contended that he did so not out of malicious intent but because of "the delusion that he was the victim of Onslow's persecution and bewitchment, which caused 'imps' to dance in his bed at night."

The prosecution, on the other hand, maintained that Arnold was a "wicked man" rather than a "madman." They also argued that Arnold's family didn't regard him as a madman, which "was shown by their frequent appeals to him to improve his life and his relations with others," since one wouldn't make appeals to someone whom they knew to be "mad."

Although Arnold was ultimately found guilty, Justice Tracy's instructions to the jury about what the definition of insanity must entail set the stage for future legal battles: "It must be a man that is totally deprived of his understanding and memory, and doth not know what he is doing, no more than an infant, than a brute, or a wild beast." According to "Partial Insanity" by Rollin M. Perkins, Justice Tracy claimed that only someone in such a state "is to be exempted from punishment."

Who was Teresa Bagioli Sickles?

Teresa Sickles was born Teresa Da Ponte Bagioli in New York City in 1836. Her father, Antonio Bagioli, was a prominent Italian singing teacher, and her grandfather, Lorenzo Da Ponte, had once worked as Mozart's librettist, so growing up, Teresa was surrounded by music. History of American Women also writes that by the time she was a young adult, she already spoke five languages.

When Teresa was three years old, a young man began studying and living with her family, according to Find A Grave. Named Daniel Edgar Sickles, the guest only ended up living at the Da Pontes' house for a little over a year, and he had to move out when his benefactor died. But it wouldn't be their last meeting. In 1851, Teresa and Daniel met once more, though by this point, Sickles had already become an assemblyman.

She was 15 to his 32, and Daniel apparently already had a reputation as a womanizer. Still, he became fixated on Teresa and proposed to her. However, "despite his prominence and long connection to the family, the Bagiolis refused to consent to the marriage," per History of American Women.

But Daniel wasn't one to take no for an answer, and on September 17, 1852, the two were married in a civil ceremony. Teresa's family finally consented, since they had little choice, and Daniel and Teresa held a second wedding, this time with Teresa clearly pregnant. Several months later, Teresa gave birth to their only child, Laura Buchanan Sickles.

Who was Daniel Sickles?

Born in 1819 in New York City, Daniel Sickles started off in the printer's trade and went on to study at New York University. It was around this time that he began living with Teresa's family, but after his benefactor died, Sickles began studying law in the office of Benjamin Butler, according to History of American Women. In 1846, Sickles was admitted to the bar.

After opening his own law practice and joining Tammany Hall, a New York City political organization, Sickles became an assemblyman by 1851 and, per HistoryNet, was elected to a seat in the New York State Senate in 1855. After serving in the Senate, Sickles moved on to the House of Representatives, and from 1857 until 1861, he represented New York's 3rd Congressional District.

Throughout his career, Sickles was always caught up in one scandal or another. Even his first law office was opened before he'd actually passed the bar. And aside from his marriage to a girl half his age, Sickles carried on obvious affairs and at one point got in trouble for bringing Fanny White, a sex worker and his mistress, with him into the State Assembly's chambers. She also ended up accompanying Sickles to England at one point, "leaving his pregnant wife at home."

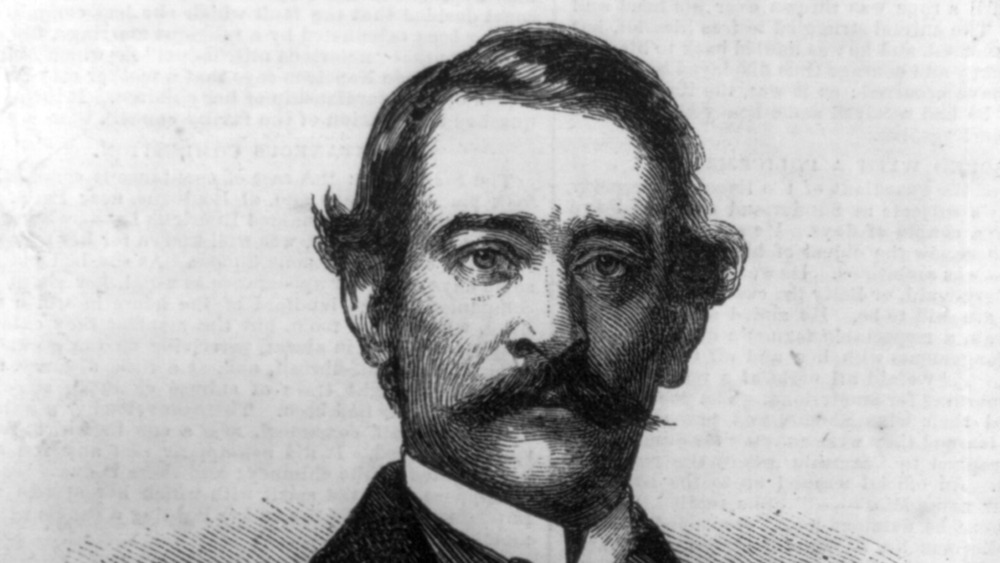

Enter Philip Barton Key II

Philip Barton Key II, son of "The Star-Spangled Banner" composer Francis Scott Key, was the district attorney of the District of Columbia when he met 21-year-old Teresa Sickles around 1857. According to J. Michael Martinez, after meeting briefly, Key began frequently visiting Teresa Sickles, and before long, they were often seen together at plays, parties, and balls.

HistoryNet writes that Daniel Sickles even encouraged them to spend time together and "often asked Key to escort his wife to social events whenever the congressman had to work late or was occupied with other women."

Before long, the affair between Teresa Sickles and Key became "the best-known secret in the Capital," since the two acted incredibly familiar and affectionate with one another in public. The Vintage News writes that Key was "known to wave a handkerchief outside his window when he wanted Teresa's company," but other accounts state that he tied a string on the door of the house where they'd meet.

Meanwhile, Daniel Sickles claimed to be entirely unaware.

An anonymous note

On February 24, 1859, Congressman Sickles and his wife hosted a dinner party at their home. After dinner, some of them decided to go to the Willard Hotel for dancing, and while some traveled in coaches, Daniel and Teresa Sickles decided to walk. On their way out, a messenger arrived with a yellow envelope for Daniel. The letter came from an "R.P.G.," whose identity is still a mystery today.

Daniel Sickles didn't read the note until the following morning, but when he finally opened the envelope, he discovered a message detailing his wife's affair. Lapham's Quarterly writes that the letter informed Daniel Sickles of a house on Fifteenth Street "where neighbors had noticed a man who did not reside there frequently tying a string or ribbon on the door."

Daniel Sickles sent a friend to watch the house to confirm the accusations of the letter, and the friend returned to inform him that he'd witnessed "a woman fitting Teresa's description entering through the rear door, and a man resembling Key entering through the front. They would stay about an hour."

Daniel confronted Teresa and, according to HistoryNet, made her write out a confession of her affair, "which she signed with her maiden name."

Daniel Sickles shoots Philip Barton Key

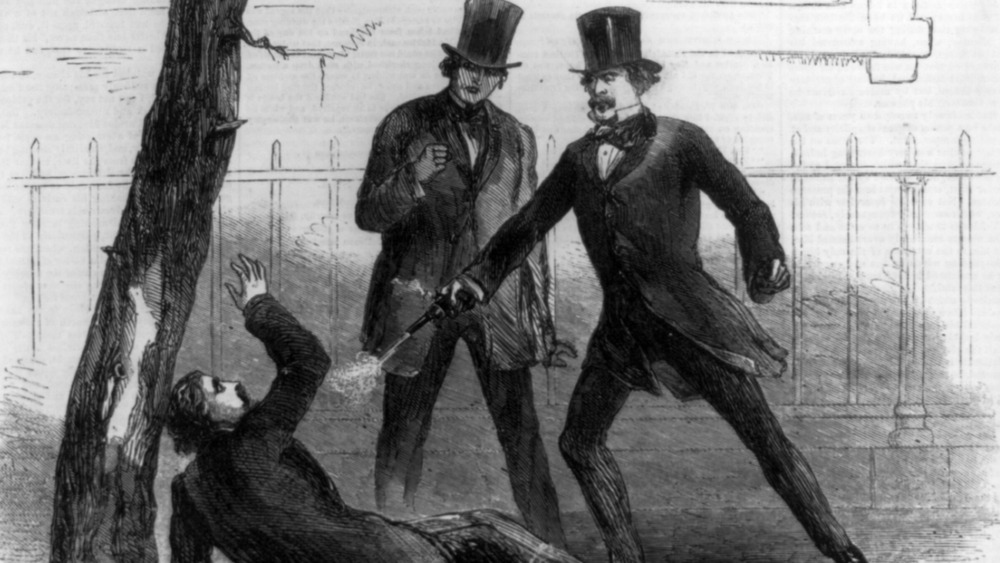

Key had no idea what was going on with Teresa and, on February 27, made an attempt to meet up with her as he'd always done. HistoryNet writes that when Daniel noticed Key signaling for Teresa outside the Sickles' house, he grabbed a revolver as well as two derringers and ran out of the house after Key.

According to Lapham's Quarterly, Daniel Sickles yelled, "Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my house — you must die!" as he gunned down his wife's lover. Daniel Sickles fired numerous shots at Key, hitting him several times at close range. As Key lay on the ground, pleading with Sickles not to murder him, Sickles called Key a villain and kept shooting at Key until his weapon misfired.

Although there were several bystanders, none of them intervened until the gun misfired and Sickles was unable to keep shooting. Key's body was taken away, and Sickles justified his actions to "anyone who would listen," proclaiming "He has violated my bed."

After discussing his options with his friend Samuel F. Butterworth, Sickles went to United States Attorney General Jeremiah S. Black and turned himself in for the murder of Philip Barton Key II.

A publicly approved murder

Even before United States v. Sickles began, most people were already on Daniel Sickles' side, including President James Buchanan, who sent Sickles a letter to show his support. According to Lapham's Quarterly, members of congress who went to visit him found him "in the head jailer's quarters" rather than being locked up like a typical murder suspect. It was even difficult to assemble a jury since so many people supported Sickles' act of murder.

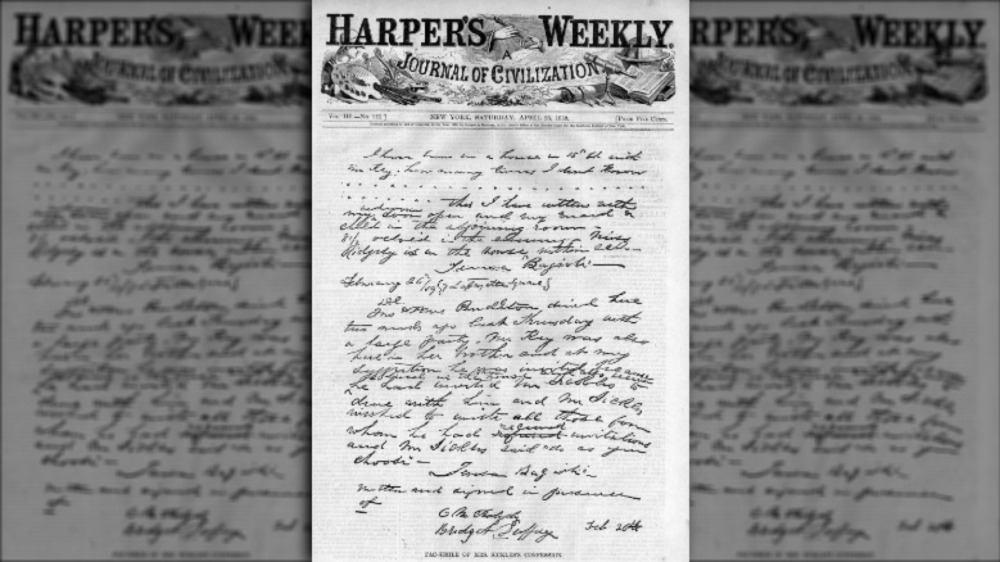

An editorial in Harper's Weekly, published before the trial started, wrote that "The public of the United States will justify him in killing the man who dishonored his bed." The New York Times agreed with Harper's Weekly, while the New-York Daily Tribune was criticized for "condemning the killing."

The Tennessee Bar Association writes that while Sickles hired three of the best lawyers in the country, President Buchanan would not appoint a special prosecutor, so the task "was left to the dead Key's young and inexperienced assistant, Robert Ould."

Trial for murder or adultery?

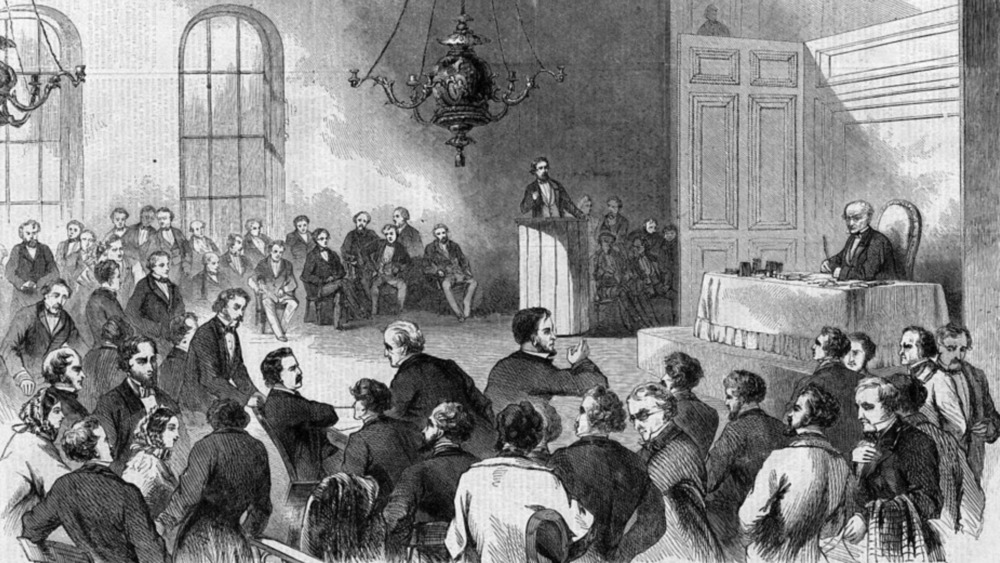

During the trial, the defense repeatedly hammered home the fact that Key was "a confirmed, habitual adulterer" and stated that a husband had a God-given right to vengeance. Defense Counsel John Graham brought up the notion of temporary insanity in his opening statement, which lasted two days, by claiming that "Sickles' provocation was so enormous that he was, from a legal point of view, insane." While defendants had pled insanity before in the United States, according to All That's Interesting, this was the first time that someone tried to use the insanity plea in a temporary capacity.

Quoting Othello and waxing poetic about the horrors of adultery, Graham claimed that, "It may be tragical to shed human blood; but I will always maintain that there is no tragedy about slaying the adulterer." However, according to the Tennessee Bar Association, despite the fact that proof of Key and Teresa's adultery was allowed into evidence, "prosecution was not allowed to introduce proof of Sickles's own adulteries."

As Thomas Fleming writes in Verdicts of History, "By now it was hard to tell whether Sickles was on trial for murder or Key for adultery." Meanwhile, Teresa was depicted as a murderer herself and claimed to have been pulled into "the horrid filth that is common prostitution." And although the confession that Daniel forced Teresa to write wasn't admissible as evidence during the trial, newspapers across the country scrambled to print "a wicked woman['s]" confession, as shown above.

Not the first crime of passion

Usually, a crime of passion requires provocation and the lack of any time to calm down. And while the prosecution demonstrated that Daniel Sickles didn't resort to drastic actions when he initially found out about the affair, the defense hammered away at the idea that "blind rage and jealousy were the natural impulses of a man who had been deeply wronged," according to Narratively.

However, this ultimately conflicted with the idea of temporary insanity, since the jury was asked to simultaneously believe that Sickles wasn't in control of his thoughts and actions "and yet engaged in the clear and noble work of defending his household." All That's Interesting writes that Judge Crawford, who was presiding over the trial, didn't buy the temporary insanity defense and stressed to the jury that since several days had passed between the murder and Sickles learning of the affair, premeditated murder was much more likely than a bout of temporary insanity.

At one moment, the defense even contended that the burden was on the prosecution to prove that someone was actually sane, but Judge Crawfod maintained that every person "is presumed to be sane until the contrary is proved; that is the normal condition of the human race, I hope."

Not guilty

The courtroom burst into applause when the verdict of not guilty by reason of temporary insanity was read after only an hour of deliberations. Daniel Sickles was led outside, and some 1,500 people took him on an "impromptu victory parade" through the streets of Washington, D.C.

With the not guilty verdict, Sickles became the first person in the United States to successfully use the temporary insanity defense. However, the public's support for him faded when Daniel and Teresa Sickles publicly reconciled. According to We're History, this ruined Sickles' reputation, but he remained married to Teresa until she died of tuberculosis in 1867. However, they never appeared together in society again.

As Narratively notes, "In 1859, it was no sin to kill your wife's lover, but to take back a fallen woman was political suicide."

Although his friends and colleagues were disappointed that Daniel Sickles decided not to divorce Teresa, in July, Daniel addressed their concerns in open letter in the New York Herald, stating that he still wished to maintain an "honorable American home" and that "I can now see plainly enough in the almost universal howl of denunciation with which she is followed to my threshold, the misery and perils from which I have rescued the mother of my child."

What happened to Daniel Sickles?

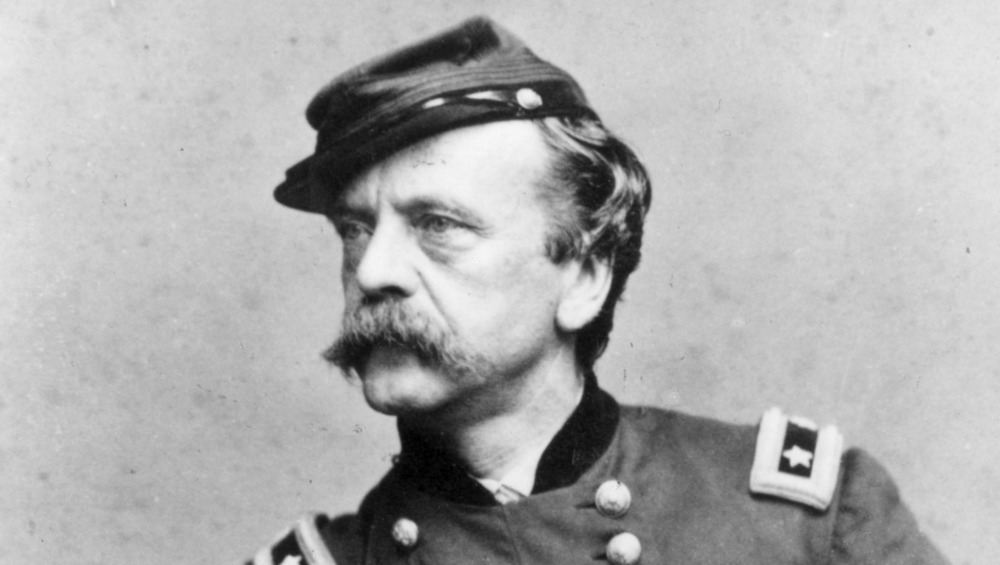

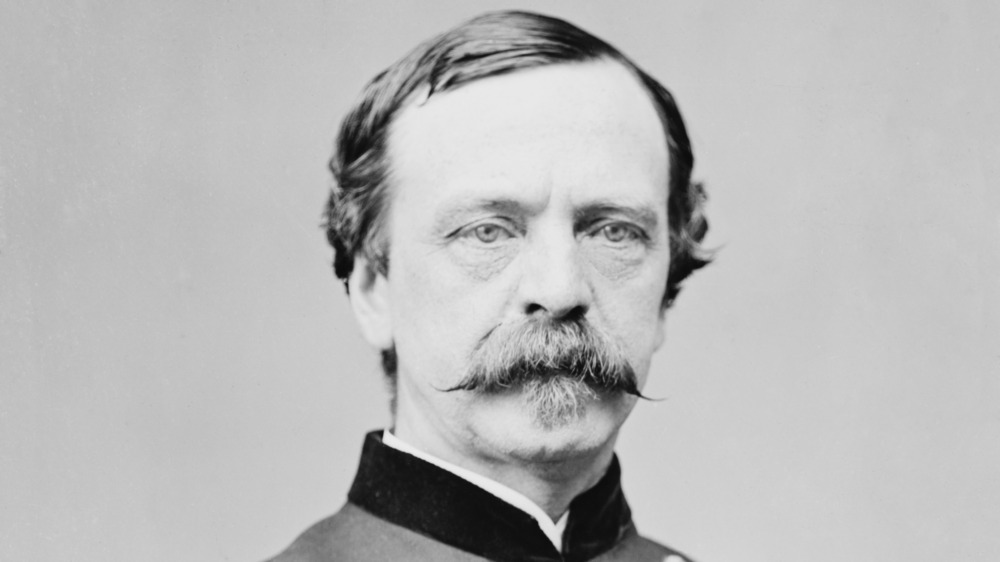

Although Daniel Sickles had to give up his congressional seat, when the Civil War began in 1861, he joined the Union army to raise a brigade. Within three years, he'd been promoted from brigadier general to major general.

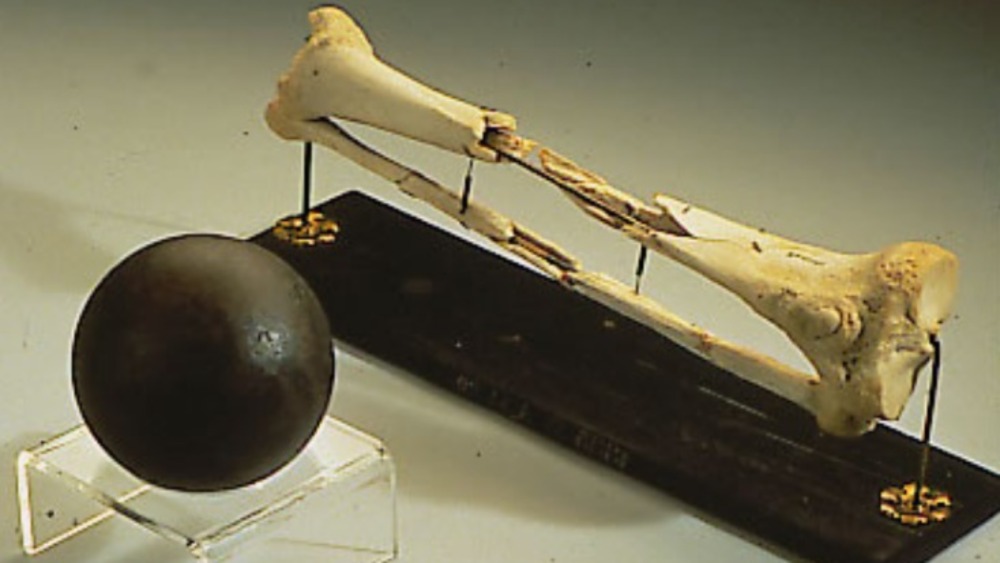

All That's Interesting writes that during the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, he disobeyed his orders and led his men into the battle. As a result, his right leg was wounded by an artillery shell and ended up being amputated. And according to We're History, Sickles "promptly sent the leg to Washington, where he supposedly visited it every July 2 for years to come" at the National Museum of Health and Medicine. For his part in the battle, Sickles was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1897

After the war, Sickles was appointed ambassador to Spain by President Ulysses S. Grant. Some claim that Sickles became so close with Queen Isabella II of Spain that the two of them had an affair, but since Sickles wasn't murdered by King Francisco de Asís of Spain, maybe not. While he was in Spain, Sickles (by then a widower) met and married Carmina Creagh, one of the queen's attendants.

In 1879, Sickles moved back to New York and "became more active in veterans' affairs when they increasingly began to return to Gettysburg in the 1880s," writes Politico. And in 1892, at the age of 72, Sickles was reelected to serve one last term in the House of Representatives.

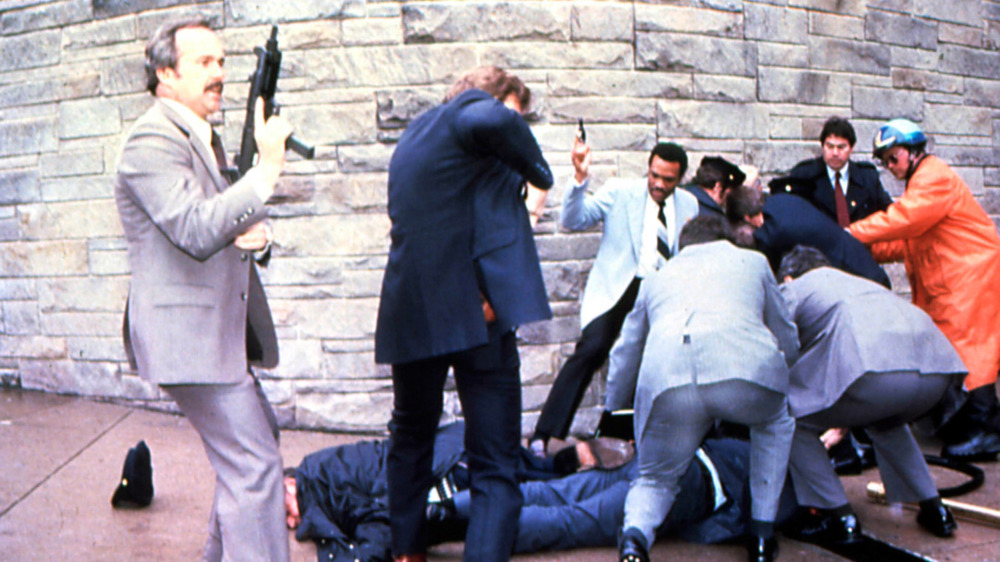

The Insanity Defense Reform Act of 1984

After Sickles' trial, the temporary insanity defense was sometimes used successfully, and it became an "unwritten law" that murder was excusable if it was found that one's spouse was in an adulterous relationship. As Narratively writes, "with men 'insanity' was a byword for an altered state, a channeling of divine justice and social honor. A woman, if acquitted under similar circumstances, was just capital-C Crazy. Usually her act was chalked up to hormonal insanity, inherent female instability or simple moral failure."

When Laura Fair was put on trial in 1871 for murdering the married man who was having an affair with her, despite the plea of temporary insanity, her defense attorneys claimed that her irregular menstrual cycle was responsible for the shooting. Although Fair was found guilty in her first trial, she was acquitted in her second, and overnight, she became a political symbol. Mark Twain even based a character in The Gilded Age on Fair.

However, the insanity plea changed in 1984, after John Hinckley Jr. was found not guilty by reason of insanity for his attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan. According to Lapham's Quarterly, the Insanity Defense Reform Act of 1984 amended insanity pleas and shifted the burden of proof onto the defense, whereas before, the prosecution had been forced to prove sanity beyond a reasonable doubt if an insanity plea was invoked.