The Truth About The Deadliest Day Of The Civil War

September 17, 1862. Sharpsburg, Maryland. The American Civil War had been raging for over a year, and the end still wouldn't be in sight for at least a few more. But history was about to be made, and not in a good way.

Union and Confederate troops clashed at the Cornfield and Bloody Lane for hours, gunfire ringing in their ears and the bodies piling up by the thousands. The men were scared, and the commanders feared for the troops under their control. Eventually, the Confederate Army was pushed back to a bridge over Antietam Creek, holding a bluff that gave them the literal high ground. But the Union eventually allowed the Confederate Army to retreat back to Virginia and declared the battle a victory.

And it was, in some ways and in the long term, but at the same time, it was sort of a hollow one. The Battle of Antietam, as the fight is now called, had a profound impact on the rest of the war, but it's more well known for its other title: the deadliest day of the Civil War. There's a lot to unpack here, including some really unfortunate (and sadly unsurprising) truths about the battle.

A high casualty count

All wars are remembered for being violent and bloody, leaving death and destruction in their wake. But just looking at the numbers, nothing in American history compares to the Civil War. And this isn't to diminish any other conflict — the statistics just speak for themselves.

According to the American Battlefield Trust, Civil War casualties numbered somewhere around 620,000 (about 2 percent of the American population at the time). That's more than American casualties in both World Wars combined and more than every other war combined until Vietnam. And that's not counting the missing, captured, or wounded. Taken all together, the casualty number is closer to 1.5 million. (Not to mention that other sources believe the death toll to be closer to 850,000, in which case, no other war or combined count is even close).

And battles like Antietam are a big part of why the count is so high — Constituting America reports over 12,000 dead, wounded, or missing on the Union side and over 10,000 for the Confederacy. But even with 23,000 casualties, it's still pretty far from the bloodiest battle of the whole war. A handful are within 10,000 casualties more, while Gettysburg has over double the casualties at 51,000. But Antietam has its own terrible title as the deadliest single-day battle, with approximately 23,000 people dead or wounded in under 24 hours. Truly horrific.

The Battle of Antietam involved close-range fighting

The fighting that took place at Antietam was absolutely terrifying, and not just because it was a battle and a lot of people died. That's true in just about any conflict. At Antietam, the fighting was up-close and personal.

So, part of the Battle of Antietam took place at the Cornfield — a literal cornfield — and that part of the battle went on for a full eight hours. But the thing about this is the fact that it was a relatively small space. From the start, the gunfire was really concentrated, opening with just 200 yards of distance between the two armies. Then from there, things just got even closer, even down to below 100 yards. Basically, at certain points, a soldier could just pop up and immediately see the enemy. Things got even worse when the Union moved south toward the Confederates holed up in Sunken Road (better known as "Bloody Lane"), but more on that later.

A hailstorm of bullets

The soldiers at Antietam had some really vivid memories of the battle, describing hours on end of being surrounded by death. And that was true, no matter the side. Sebastian Duncan recalled the fear at hearing shots whizz over their heads, the shells bursting into splinters above them as all the men ducked on instinct, even if the shots were passing more than 100 feet over them. Eventually, they realized the distance, but that didn't make anyone brave enough to try and poke their heads up for a better view. And with muskets rattling waves of gunshots through the air like explosions, who could blame them?

But for others, the bullets truly did rain down on them: Thomas Evans wrote how, sometimes, the shells were exploding just over their heads, showering them in shattered bits of metal. Another soldier, Robert Kellogg, had a shell burst so close to him that it blew dirt right into his face. With bullets flying through the air, knowing they were hitting so close, the instinct was just to hope for a little luck and stay out of the way.

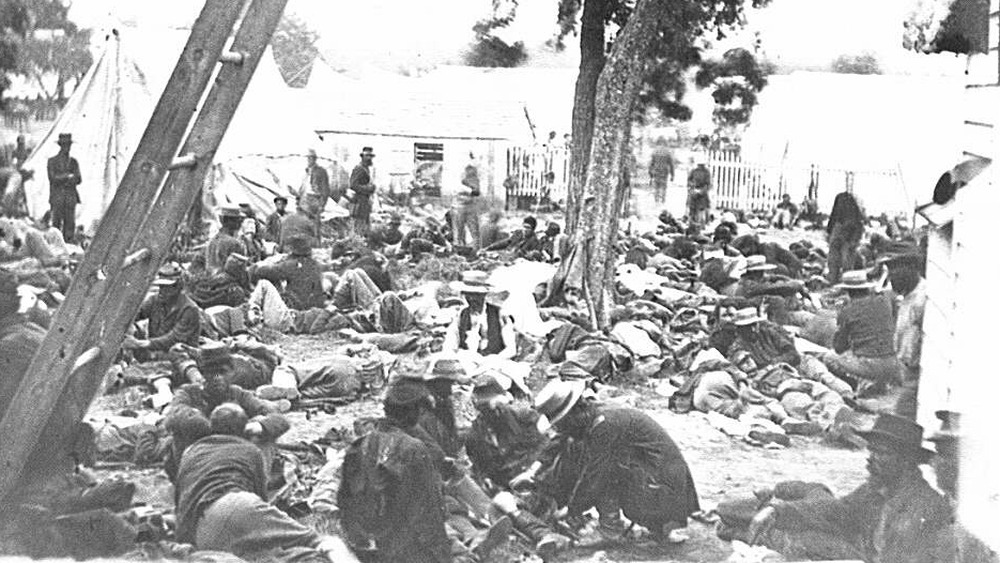

The scene at the hospitals

It's no far stretch to call Antietam the bloodiest day in all of American military history. The devastation on the battlefield itself — in the midst of all the fighting — is one of the places that anyone could've seen that. But William Child, a surgeon writing from a battlefield hospital near Sharpsburg, believed that, maybe, it was the days after the battle that might have been even worse .

In the aftermath of the battle, his work was never-ending, dressing wounds quite literally from dawn 'til dusk for multiple days on end. George Allen added that, in most cases, the wounded were basically piled into the hospitals, tightly packed together, where they awaited treatment (which was, more than likely, going to be amputation). But the part that was really bad was the difference between the dead and the wounded.

A bunch of soldiers described the carnage on the battlefield, painting horrifically vivid images of their fallen comrades, but at least the dead were just gone. The wounded had to suffer through intense and burning pain, the kind that's too hard to think through, and it wasn't easy for them or the doctors who treated them. It was all so bad that Child believed it was an act of God — punishment for a great sin. "I pray God may stop such infernal work," he wrote in a letter to his wife (via the National Park Service).

Bodies falling on the battlefield

It's really, really easy to find accounts of this battle that are just filled with gruesome and horrifying imagery, the things that the soldiers saw as people fell left and right. Soldiers struck by a bullet would be sent sprawling backwards, and any of them not immediately killed from a shot to the head or heart would be left to writhe in pain. Christoph Niederer had an even more disturbing story: He felt a blow to his shoulder but also something wet splatter on his face. Looking over, he saw a fellow soldier "lacked the upper part of his head, and almost all his brains had gone into the face of the man next to him" (via HistoryNet). There really isn't much more that needs to be said — it's just a terrifying image.

But aside from the blood and gore, there are other stories that are just sad. One soldier staggered in the midst of battle, not from a wound, but from finding his father lying dead on the ground. Union Major R.R. Dawes wrote about his captain owning a dog that was loyal all the way until the end, by his side as he fell. J.D. Hicks found the body of a teenaged drummer boy — not even a soldier — pale and lifeless with a bullet in his forehead, but a smile still on his face and his drum lying next to him, "never to be tapped again."

The soldiers all had families

This is one of those things that everyone knows, but it just sort of deserves to be said. All of the soldiers in this battle were people, not just numbers on a casualty list. All of them had families, and no small number of the accounts of the battle come from letters. A lot of them just missed everyone back home, wanting little more than to see them again, hoping for letters and the happiness they got from being able to hear from them, at the very least ). Many times, those letters would also include individual things to tell different people back home — personal and more intimate responses.

And there are stories filled with a lot of longing. William Child wrote to his wife about a dream he had, where he was back home, back in his normal life, feeling like the dream was real. "I love to dream of home it seems so much like really being there," he wrote (via the National Park Service). It reads kind of like a scene in a movie, lingering a bit on the moment when he got to be with his wife — when she kissed him and told him that she loved him. It's intimate and bittersweet, a dream in the middle of him tending to so many wounded. Another soldier also wrote home, not sad or despairing over his wounds, but over the fact that someone had stolen something priceless from him: A book containing a lock of his wife's hair.

The Battle of Antietam wasn't meant to be important ...

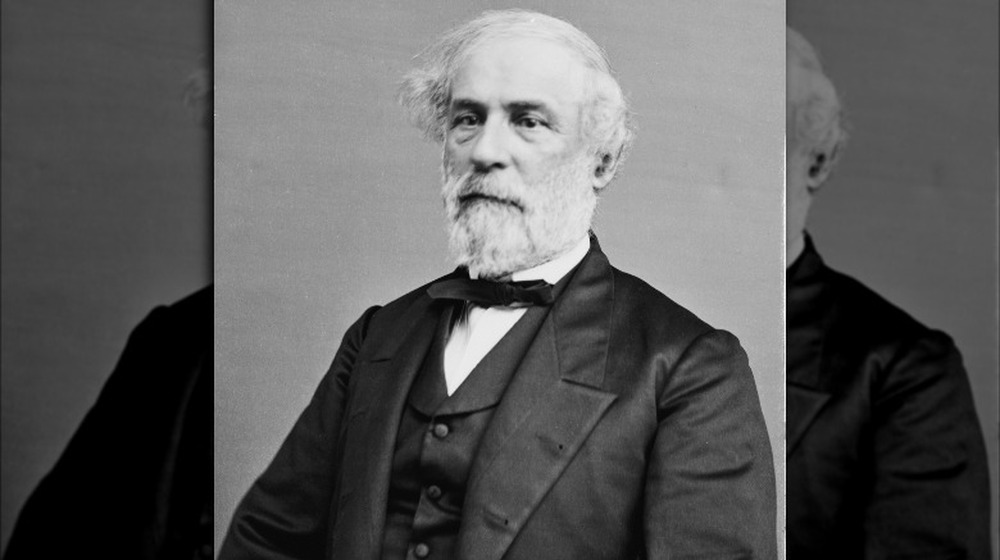

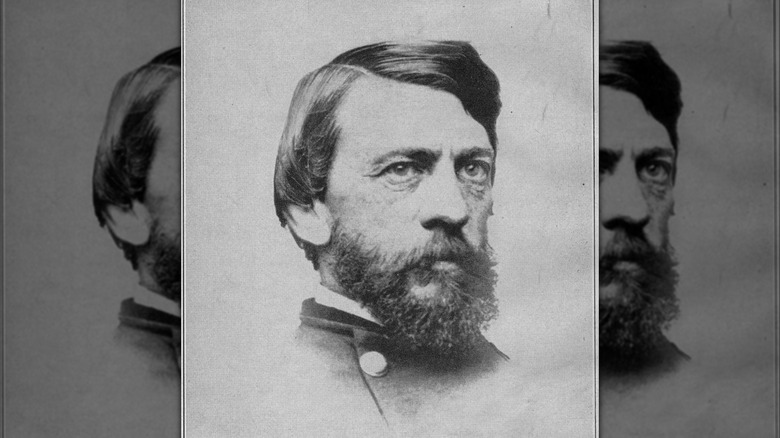

It was 1862, and things weren't going well for the Union. There were a number of reasons why, but it mostly came down to demoralization and a few less-than-flattering military losses. That gave the Confederates an opportunity, one that General Robert E. Lee (pictured) was going to capitalize on. He knew that invading Maryland would end up being a real blow to the Union as a whole, as the Confederacy could really go on the offensive and start encroaching on Union lands. That spawned the Maryland Campaign, Lee's ambitious plan to pretty much sweep through the state and capture Union-controlled areas.

Here's the thing, though: Antietam wasn't exactly part of those plans. The creek wasn't a strategic position — it's just where the Confederate army fell back to when things went awry. At best, it would just be a place where they could launch a larger campaign farther north. A Confederate victory up north could have meant something. Antietam itself didn't really mean much — the actual lines only shifted about 100 yards total. That said, it could've been insanely important, yet McClellan allowed Lee to retreat and regroup and refused to pursue him, feeling he'd done his job.

... And it didn't have to happen

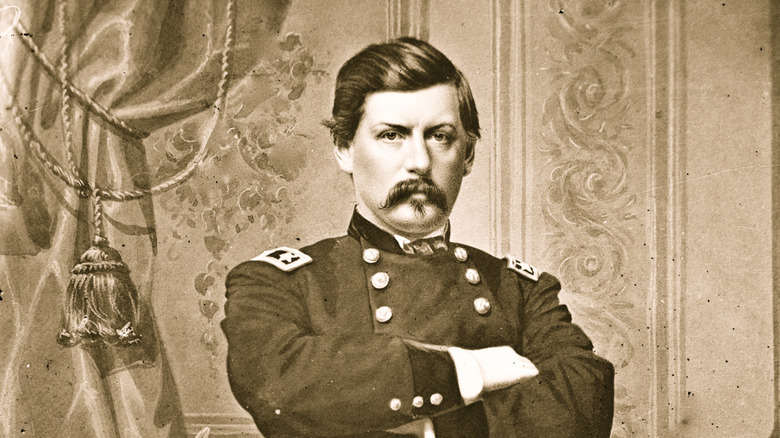

On September 13, the Union army under General George McClellan (pictured) was stationed just outside Frederick, Maryland. Sergeant John Closs and Corporal Barton Mitchell happened upon a lucky find: Three cigars discarded on the ground. But it was more than that. A paper was wrapped around them, addressed to Confederate General D.H. Hill and titled "Special Order No. 191."

This was a major find. McClellan and the Union had been completely confounded by Lee's strategies, but suddenly, they had their hands on the Confederate army's exact plans, coming directly from Lee's adjutant general. Suddenly, they knew that Lee's army was spread thin, separated into five parts over 30 miles, and not even that far away. It was a massive tactical advantage.

Except, McClellan did nothing about it. The Union could have completely decimated the Confederate army in one fell swoop. The soldiers could've taken their enemies out piece by piece — a bunch of small battles between a tiny army and a much larger one. It would've been the easiest Union victory, and one with a relatively small casualty count. But McClellan completely squandered the opportunity. He took a full 18 hours to mobilize his troops, at which point Lee already guessed the Union knew about his plans and had regrouped his forces, and then the bloodshed of Antietam wasn't far behind. As Lincoln pointed out to him, McClellan could've decimated the Confederate Army right then and there. He might have been able to win the war that day, but the chance slipped away.

General George McClellan made some very curious decisions during the battle

Major General George McClellan was commander of the Union Army amid the Battle of Antietam, but seeing as he's now remembered as one of the worst generals of the Civil War, perhaps he shouldn't have been. The first of his odd decisions regarding Antietam (the only full battle under his command) was to convince himself that 120,000 Confederate troops were bearing down on Sharpsburg. In reality, 45,000 Confederates met 87,000 Union soldiers there. Besides conjuring a phantom army, McClellan was oddly reluctant to tell his generals what he was planning or give clear orders in the midst of battle. Indeed, he actively undermined command of his least-favored generals.

Odder still, as we just mentioned, was that McClellan had intercepted Robert E. Lee's battle plans ahead of time, yet did practically nothing with the intel. The plans indicated that Lee wasn't interested in advancing on Washington, D.C., and gave McLennan forewarning of Lee's intent for the earlier Battle of Harpers Ferry, further forcing the Confederate military leader into uncomfortable positions days later at Antietam. But McClellan was strangely sluggish at Antietam, allowing Confederate forces to muster into stronger positions while he dilly-dallied. He also allowed Confederate troops the chance to retreat, though whether that was by design or through incompetence is hard to determine over a century and a half later. However it happened, McClellan hardly earned a glowing performance review. After an increasingly tense series of events, President Lincoln removed McClellan from Army command in November 1862.

Photographs of Antietam brought the battlefield home

The Civil War saw a pretty important first in history: Antietam was one of the first battles to ever be photographed, showing the tragic, harsh realities of war. See, photography had just become a thing earlier in the century, the first photographic images getting produced in the late 1830s. But the entire process of producing photographs was ... complicated. It's the entire tedious process with darkrooms, but with some added layers of complexity that come from using necessary chemicals that had to be handled with a lot of care.

So battlefields were generally "too chaotic" for photography, as The Met puts it. Photographers definitely couldn't get any footage of the battle itself, but they could document the preparation and the aftermath. And that's the big part: the aftermath. Antietam was the first battlefield photographed before the dead were buried. The first battlefield that anyone could see, littered with the bodies and the dead and all. Those photographs went up into galleries, and for the first time, people at home could see just how terrible war was — how bloody and grim it was — without ever being there themselves. All of a sudden, the battle was brought right to their doorstep, and they could just about see it all firsthand.

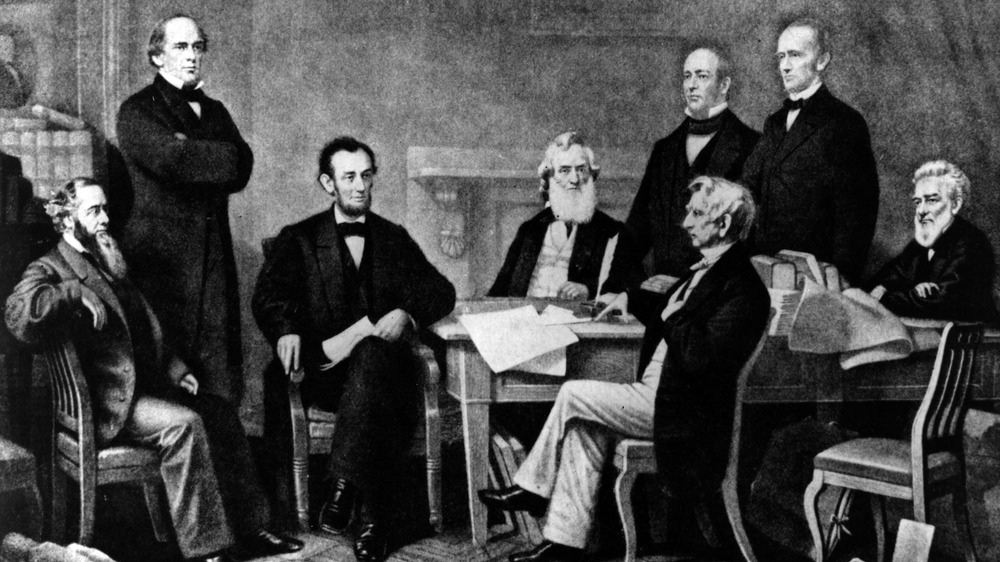

The Battle of Antietam led to the Emancipation Proclamation

The Battle of Antietam has become infamous for the amount of blood shed in such a small amount of time, but it's also become famous for other reasons, like inadvertently changing the tide of the Civil War. At the time, President Abraham Lincoln had been intending to find a way to end slavery. His solution to that problem was the Emancipation Proclamation — a document that would free enslaved peoples in the South as a part of Lincoln's wartime powers (while exempting those in the border states in order to keep those states from running into the arms of the Confederacy).

But the Union wasn't in a great place at the time when Lincoln first penned it. Union morale was already low, the military was despairing because of lost battles, and the public at large was frustrated with how long the war was taking. So Lincoln's cabinet was worried about him delivering such a speech — there were too many things unsure, and they counselled him to wait for a military victory. It would be best to deliver the Emancipation Proclamation from a place of strength.

Antietam was exactly that. Casualties were high (to the point that many historians would actually call the battle a stalemate), but the Union claimed it as a victory regardless. It was the best chance the Union was going to get, and so Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves as of the start of 1863.

Europe stayed out of the Civil War because of Antietam

The Union had a lot to deal with in 1862: A demoralized army, disappointing military defeats, unpopular legislation, and the like. But there was another looming problem: Europe. Europe imported Southern cotton, and they might end up recognizing the Confederacy. Backing by a major European power could really change things.

And that was a really legitimate concern, as Europe was definitely watching from the sidelines. England and France had initially stated their neutrality, their respective governments not willing to support rebels who believed in slavery (both countries had already abolished the practice) and expecting a quick Union victory. But that quick victory didn't happen, and the two European powers started to reconsider. European nobility identified with Southern gentility, and the governments thought that the U.S. was becoming too powerful in world affairs. The nation splitting would reset the balance of power. Plus, the Confederacy proved their military capability, and an international incident painted the Union badly. And this war wasn't — officially, at least — just about slavery. After all, supporting the Confederacy didn't necessarily have to equate to supporting slavery in the eyes of other countries, so maybe it wouldn't be the worst idea.

Antietam flipped that around, though. It gave the Union a victory, and then it led directly to the Emancipation Proclamation. Suddenly, the war was about slavery, and the Confederacy was the villain for supporting it. At that point, European powers pulled out entirely — they couldn't support the Confederacy without their people hating them.

Sunken Road was a notoriously bad spot

Sunken Road was once an unremarkable byway near Sharpsburg, but the Battle of Antietam turned it into a scene of horror. As the conflict commenced, Confederate Colonel John Brown Gordon assured General Robert E. Lee that the 2,200 men under his command would hold their position on the road "till the sun goes down or victory is won" (via the National Park Service). However, that proved daunting when almost 10,000 Union soldiers focused their efforts on taking Sunken Road. Even when another Confederate general sent 3,800 troops to support those already at the road, it was fruitless.

By midday, the Confederates had retreated. As William H. Osborne of the 29th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry recalled (via Project Gutenberg), "The shouts of our men, and their sudden dash toward the sunken road, so startled the enemy that their fire visibly slackened, their line wavered, and squads of two and three began leaving the road and running into the corn." Though Union forces proved technically victorious and took the position, there were terrible casualties on both sides. An estimated 5,500 soldiers were killed or wounded at Sunken Road alone, which quickly came to be known as "Bloody Lane."

Even presumably battle-hardened witnesses were shocked to survey the carnage. "What a bloody place was that sunken road," recalled Charles A. Hale of the 5th New Hampshire Infantry (via HistoryNet). "[T]he fences were down on both sides, and the dead and wounded men were literally piled there in heaps," he added.

Clara Barton truly distinguished herself during the battle

Today, Clara Barton is remembered as a pioneering educator and nurse who saved lives on Civil War battlefields, identified the unknown dead, and later established the American Red Cross. But part of her potentially untold truth is that she rose to real prominence with her work at Antietam. Having begun work as a nurse barely more than a year before, Barton arrived at Antietam just before the battle began, for what would be her first time encountering active combat. Over the next 36 hours, she delivered supplies, aided the wounded (including helping to move them to cover), prepared much-needed meals, and provided lighting for doctors as night fell.

She brought much-needed bandages and other supplies to surgeons (who in some accounts had resorted to using corn husks) and began ministering to the wounded, oftentimes at great risk to herself while projectiles flew around her. Per her own account, Barton was tending to a wounded man when she felt a bullet pass through her sleeve, narrowly missing her torso. But it had hit the soldier she had been helping, Barton soon realized. "There was no more to be done for him and I left him to his rest," she recalled (via the National Park Service). In a letter after the battle (via the Clara Barton Museum), surgeon James Dunn referred to her as "the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battlefield," an epithet that stuck thereafter.

The ambulance corps of Jonathan Letterman saved lives

Within the Union Army, the ambulance corps headed by Dr. Jonathan Letterman saved thousands of lives at Antietam. Letterman joined the U.S. Army in 1849 as a newly minted assistant surgeon and, until the commencement of the Civil War in 1861, was part of numerous military actions (many targeting Indigenous Americans). By 1862, he was the Army's medical director, and he was given the daunting task of revamping its battlefield medicine.

Those medical practices were grim at best. In the early campaigns of the war, wounded soldiers were often left stranded and in great pain. Letterman's innovation was to put together an Ambulance Corps, consisting of soldiers trained to carry men off battlefields and load them onto wagons. These corps members were also trained in triage to assess the nature of battlefield injuries and determine each soldier's prognosis. From the battlefield, soldiers would be taken through a three-stage system that began with a field dressing station, moved to a nearby field hospital (often an ersatz arrangement in a local building), and then, if necessary, a long-term hospital.

While Antietam was undeniably bloody and later battles like Gettysburg were potentially worse than you thought, Letterman's Ambulance Corps (as well as his improved methods of delivering medical supplies) made a demonstrable difference. Unlike earlier battles where the wounded lingered in pain on the field for days, all of the still-living casualties at Antietam — some 17,000 in total — were recovered within 24 hours and sent for life-saving treatment.

Civilians had to grapple with the battle's violence

Civilians who made their home in and around Sharpsburg in the fall of 1862 were also hit hard by the Battle of Antietam. With troops assembling around the town, non-combatants faced the difficult choice of staying in place or fleeing. The town itself was officially under Confederate control and was likely to be hit by Union guns, but leaving homes, farms, fields, and other holdings meant leaving them vulnerable to fighting and hungry, desperate soldiers. Horses were a particular target, as both armies seized them — no matter if the animals were vital to someone's livelihood. The Roulette family stayed on their farm but saw it converted into a Union field hospital where family goods were seized, including textiles, beds, and kitchenware. An estimated 700 soldiers were buried on the property (with no one bothering to ask the Roulettes first).

Others were forced to leave. The Prys, another local farming family, lived in a nice brick home that became officers' quarters for General George McClellan and his staff. The surrounding property turned into a campground for the Second Corps, which consumed the family's food supplies, stole hay (and killed the animals that would have eaten it), and even burned fencing for campfires. Though Philip Pry, the family's father, filed multiple claims against the government for this incursion, he wasn't paid until years later (and the government even demanded some repayment). Financially devastated, the family moved to Tennessee in 1873.

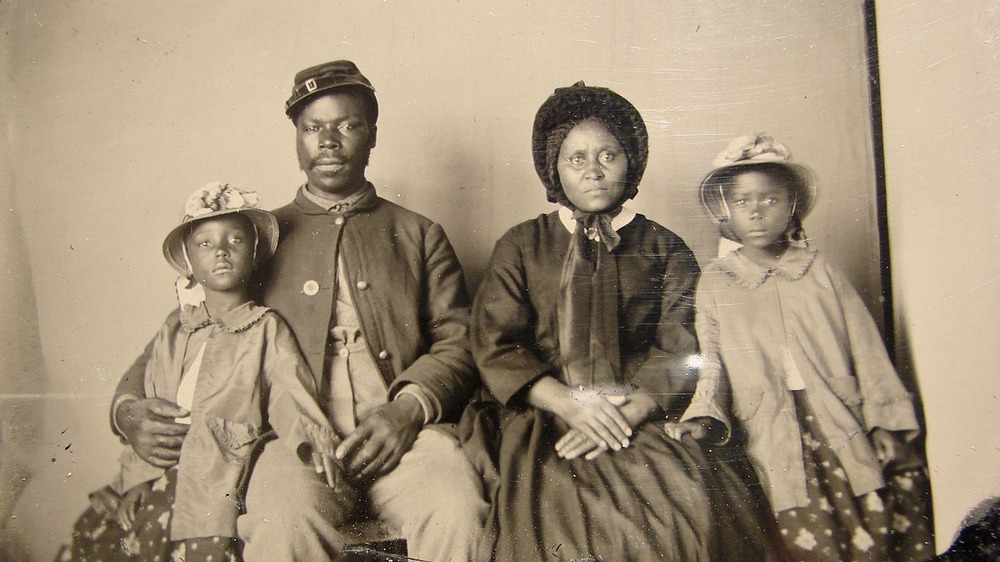

Black Americans were uniquely affected at Antietam

As mentioned, the Emancipation Proclamation, officially enacted after Antietam on January 1, 1863, declared enslaved people living in rebel states to be free, but not those living in Union border states — including Maryland. Both enslaved and free Black Americans lived in the area at the time of Antietam, and some were owned by noted Union supporters. Anti-slavery abolitionists had a poor reputation there, too, while local authorities sometimes announced intentions to capture and return escaped enslaved people.

As war approached Sharpsburg and Confederate troops threatened to overtake the town, some Black residents moved even farther north (though some were compelled to join Union troops, as was the case for the teenaged Jeremiah Cornelius "Jerry" Summers, who was retrieved by the Piper family that claimed to own him). Those who remained, whether by choice or compelled to do so, encountered hungry troops (sometimes cooking for them) and weathered the artillery barrage.

True to its reputation as a major presidential game-changer, the Emancipation Proclamation helped pave the way for enlisting Black soldiers in the Union Army, an effort that only really began in the first months of 1863. Eight Black men from Sharpsburg, five of whom were enslaved, enlisted with the Union after the Battle of Antietam. The teenaged Summers attempted to do the same, but he was retrieved again by the Piper family. Later that year, he was freed under new state legislation but continued working for the Pipers for pay.

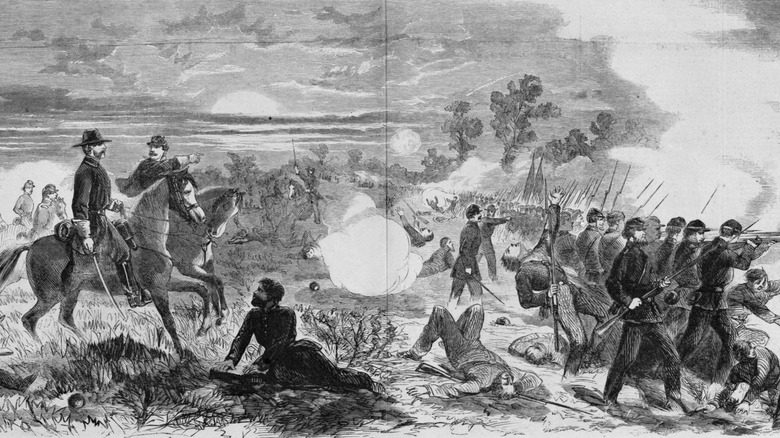

Miller's Cornfield saw some of the worst fighting

Where was the worst fighting at Antietam? One inglorious candidate is Miller's Cornfield. The stretch of 24 acres saw a combined 25,000 Union and Confederate troops battle for almost three hours. "It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battlefield," Union General Joseph Hooker recalled (via the National Park Service). The skirmish produced an estimated 8,000 casualties.

Miller's Cornfield belonged to the Miller family — specifically, David R. Miller, his wife Margaret, and their children. When it became apparent that a major battle was about to happen, they left their home north of the town and traveled into Sharpsburg to shelter with family. Upon returning, they were confronted with the carnage of what had happened in their field. Their home and barn were intact, but the corn crop was ruined — some wounded soldiers were still lingering in the field — and practically all of their stored food had been seized and handed out to Union soldiers.

Like other soldiers who died in battle during the Civil War, those who died were buried nearby ... meaning the Miller fields became a massive graveyard. Though some bodies were exhumed and reburied elsewhere, that process took years, and not all of the estimated 5,000 graves were identified. In fact, one hiker stumbled across a long-forgotten grave there in 2008 (the unnamed soldier was identified as a member of a New York company and reburied in Saratoga National Cemetery).

Both sides used intense artillery

Artillery at Antietam played an especially noticeable and frightening role, to the point where Confederate Colonel Stephen D. Lee said that the battlefield was "artillery hell," recalling the terrible effects of Union artillery on troops under his command (via Antietam on the Web). All told, over 500 cannons and large guns were deployed by both sides during the battle, producing tremendous, nearly constant noise that survivors described as a deafening, deadly thunder. Dedicated artillery units of eight soldiers each moved relatively quickly around the battlefield, maneuvering wheeled weapons pulled by horses.

Soldiers moving across the largely unobstructed land of Antietam were faced with deadly barrages from these units, which could mass cannons together in groups of up to 24 large guns. Smoothbore cannons used on the field were less accurate than their rifled counterparts but could also fire 12 pounds of ammunition over 1,600 yards (depending on the exact model). Rifled cannons were more accurate and were largely held by Union forces (about 60% of Union artillery was rifled compared to an estimated 40% for Confederate forces).

As for ammunition, solid cast iron shot was more accurate than shells and certainly proved devastating. But shells, cases, and canister-style ammunition produced more noise and could fling deadly shrapnel at approaching forces. Both soldiers and civilians — some of whom recalled sheltering for an agonizing stretch of days in cellars as the air outside boomed with bursting shells — were witness to the devastating effects of artillery.

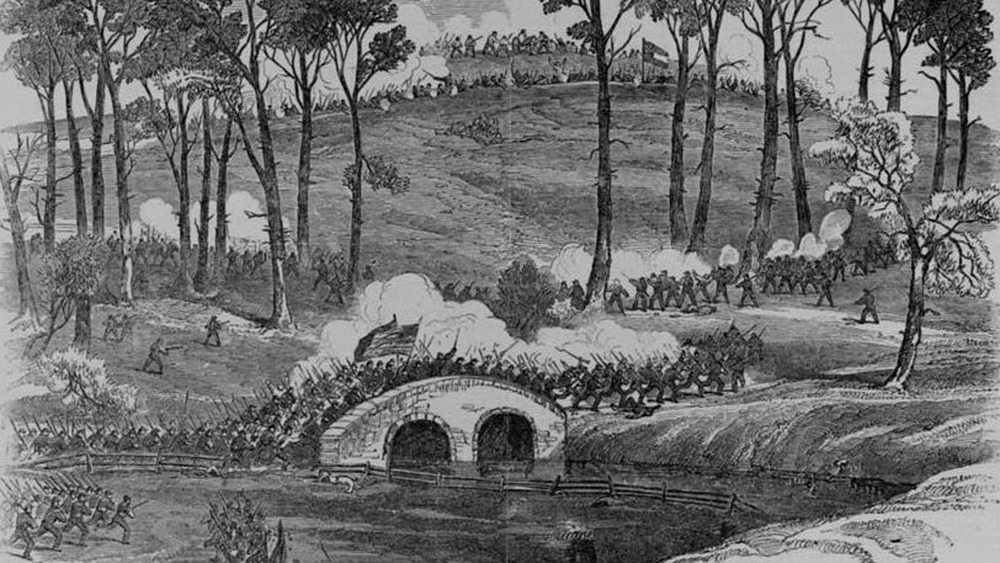

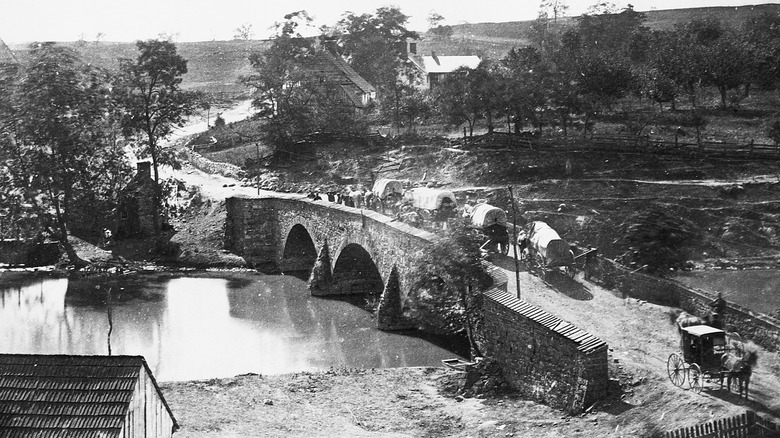

Burnside Bridge was a hard-won victory for the Union

Burnside Bridge was a key point in the landscape of Antietam. Spanning Antietam Creek, it allowed key movement of troops and equipment from the south. Confederate troops defended the position at first, but after more than three hours of Union assault, they were nearly surrounded. With Union Brigadier General Isaac P. Rodman's 9th Corps having crossed the creek a short march south of the bridge by the middle of the day, Confederate General Robert Toombs was forced to order a retreat.

The process in which Union Major General Ambrose Burnside and his troops finally took Burnside Bridge turned out to be a rather uncoordinated one. To that end, some historians have since alleged that if Rodman and his soldiers had crossed Antietam Creek earlier, the Union victory would have been far more decisive and perhaps far less bloody. The argument goes that, if Union Army commander Major General George B. McClellan or another of his officers had better directed troops and had more accurately identified a good spot to ford the creek, Rodman's division wouldn't have wasted time finding a better place to cross. Or perhaps staffers confused reconnaissance data and directed forces to the wrong place. Things get even more thorny when you realize that quite a lot of the controversy stems from postwar memoirs, which perhaps took already complicated battlefield experiences and made them all the murkier with the passage of time.