Musicians Who Couldn't Stand The Beatles

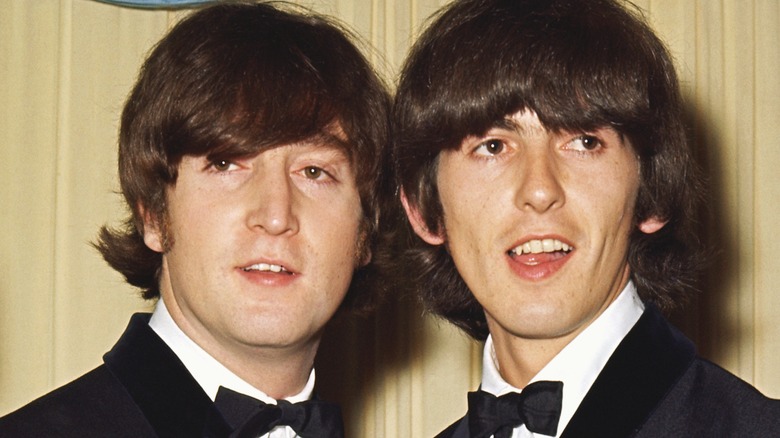

It's a hard concept to wrap one's mind around, but there's a significant number of people out there — famous, professional, and important musicians even — who just don't care for the Beatles. Music is all subjective, a matter of taste, but the Beatles are as objectively good or as universally beloved as any musician is ever likely going to be. Collectively, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, George Harrison (and their guiding producer and arranger George Martin) have sold more albums than anybody ever has; have amassed more No. 1 hits in the U.S. and in the U.K. than any other band; and are responsible for so many elements and tropes of rock 'n' roll and pop music.

Still, not everybody can dig that well-known Liverpudlian sound. Many other influential, popular, and highly regarded musicians have gone on the record with reporters to denounce the Fab Four and let the world know that they're not on board with the world's favorite band. Here are the musicians and artists who just plain loathed the Beatles.

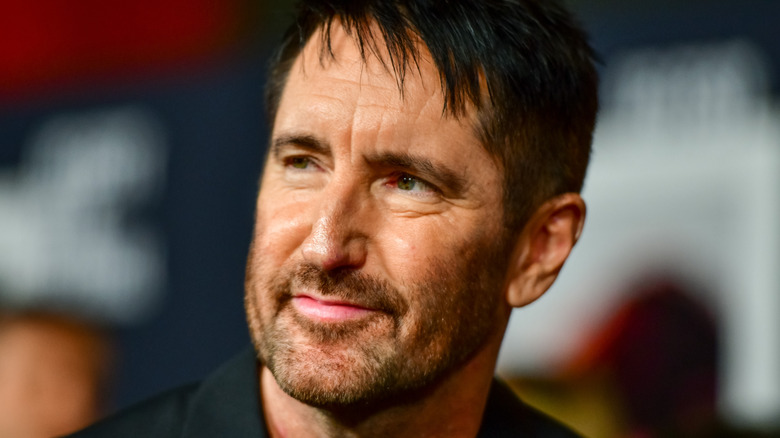

Trent Reznor

As the frontman and only continuous member of Nine Inch Nails, Trent Reznor has used his band to explore the dark side of humanity. Nine Inch Nails have sold millions of copies of albums full of sinister industrial alternative metal like "Down In It," "March of the Pigs," and "Closer."

In 1994, Reznor told Plazm that he'd been listening to a lot of older music at the time such as Davie Bowie's '70s output. It made him realize that contemporary music paled in comparison to that stuff, as did the music that Bowie followed. "I hate to think in a retro mindset. You know, 'the Beatles were the best thing.' F*** the Beatles, I hated people who were always going on about the f***ing Beatles. They're dead. They're ugly now. Get them out of my sight."

Reznor's harsh opinion softened over time. In 2011, Rolling Stone asked the musician, who'd just won an Academy Award for scoring "The Social Network," who he thought could be labeled a genius. "It's so obvious, but the Beatles," Reznor said. "When I was growing up, the people who liked the Beatles, I didn't like, so I didn't pay attention to them." He explained that around the time of the release of the Nine Inch Nails album 'The Downward Spiral' — which he was promoting with the Plazm interview — he started to listen to a lot of latter-day Beatles records. "They were so far ahead of the game, it's just not fair."

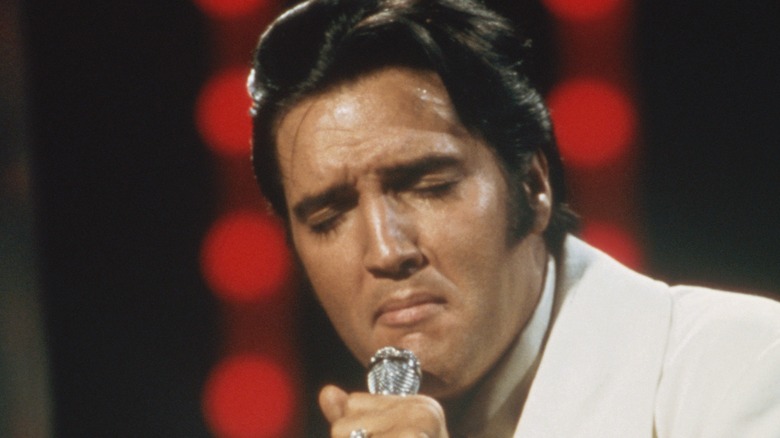

Elvis Presley

In 1970, as recorded in the National Archives, Elvis Presley, the King of Rock n' Roll, wrote a letter to President Richard Nixon expressing worry about the direction the U.S. was heading, particularly with the rising popularity and influences of drugs, hippies, and the Black Panther Party. "Sir, I can and will be of any service that I can to help The Country out," Presley wrote. "I can and will do more good if I were made a Federal Agent at Large and I will help out by doing it my way through my communications with people of all ages."

That correspondence gave way to a 1970 Oval Office meeting and a lasting friendship between Nixon and Presley. Per a summary prepared by Nixon's associate Bud Krogh, also recorded in the National Archives, the duo discussed the concerns raised in the letter. Then Presley cited the Beatles as one of the chief negative influences on America's youth. "[H]e thought the Beatles had been a real force for anti-American spirit," Krogh noted. "He said that the Beatles came to this country, made their money, and then returned to England where they promoted an anti-American theme." In response, Nixon "nodded in agreement and expressed some surprise."

Ray Davies

After the Beatles made it big in the U.S. in 1964, a variety of bands from England rode that success to international fame and fortune of their own. Among those other "British Invasion" acts that helped define '60s rock were the Rolling Stones, the Who, and last but not least, the Kinks. Brothers Ray and Dave Davies of the Kinks drove the band's musical direction, and they'd record timeless, gritty pop-rock hits with "You Really Got Me," "Picture Book," and "All Day and All of the Night."

The Beatles' 1966 album "Revolver" is one of the most critically celebrated albums of all time. Just before its release, music magazine Disc and Music Echo (via KindaKinks) gave Kinks frontman Ray Davies an advance copy and let him write a track-by-track review. Davies was left decidedly underwhelmed by the classic in the making. He likened "Taxman" to a mixture of the sound of the Who and the theme song to the '60s "Batman" TV series. He found "And Your Bird Can Sing" to be "too predictable," and called "I Want to Tell You" "not up to the Beatles' standard." But Davies clearly hated "Yellow Submarine," writing, "This is a load of rubbish, really. ... I think they know it's not that good."

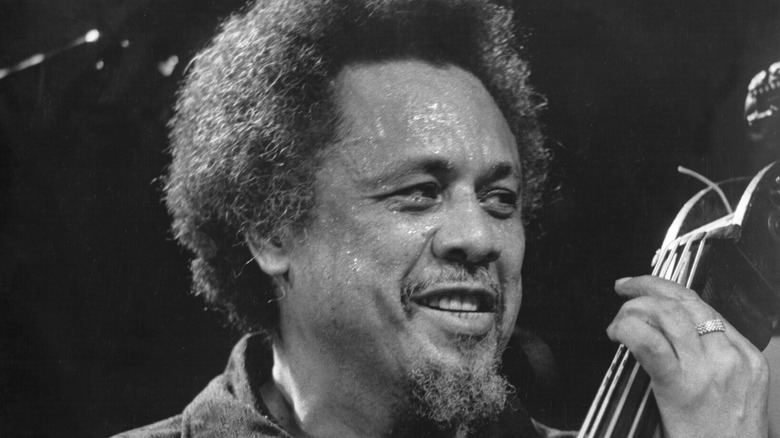

Charles Mingus

A towering figure of jazz in the mid-20th century, Charles Mingus took his genre to new heights as a bassist, pianist, composer, bandleader, and music theorist. He ranks with the all-time greats of jazz, with whom he often collaborated, including Charlie Parker and Miles Davis.

Mingus didn't merely dislike the Beatles' songs and sensibility — he pointedly discredited and called into question everything they did. Many have accused the Beatles of unfairly using music from Black musicians, a sentiment Mingus reflected in his autobiography, in which he declared the British band to be thieves and frauds. "For the Beatles to be able to come here and take all the millions of dollars away from this country by copying our own music and composers, selling it back to 'em and nobody even suing 'em yet!" Mingus wrote in "Mingus Speaks."

Mingus considered the Fab Four to be pawns in a grand conspiracy. "They stole what we call rock, studied it — not the Beatles did it but some great classical minds from England," Mingus explained. "And they built the Beatles and the Beatles was a machine, and they promised these kids so much money, and they trained them. They were not musicians when they came."

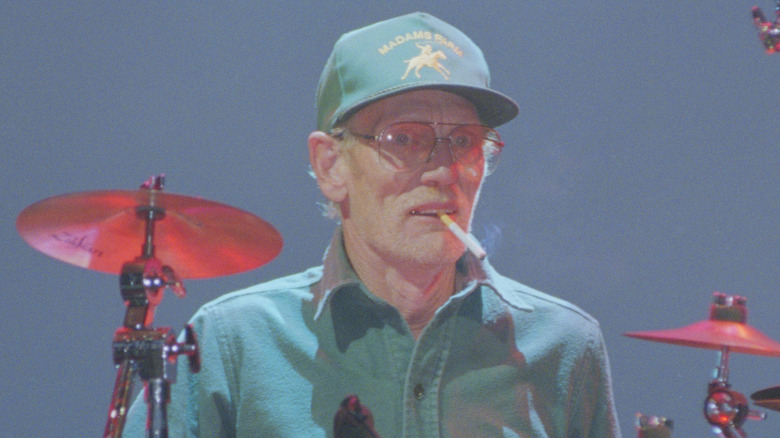

Ginger Baker

While British Invasion rock bands hit the charts, young virtuoso musicians across England embraced American-style blues and combined this style with rock elements to create something new. One of the loudest, heaviest, and most popular of those blues rock bands was Cream, whose three members got a whole lot of sound on psychedelic-tilting classic rock standards such as "Sunshine of Your Love," "White Room," and "Badge." Cream was a supergroup, consisting of guitarist Eric Clapton, bassist Jack Bruce, and drummer Ginger Baker.

In a 2015 interview with Forbes, Baker expressed disdain for professional musicians who can't read or write musical notation such as heavy metal performers and a certain Beatle. "Even Paul McCartney needs someone to write it down for him. And he thinks that's good," Baker said. "There was an article where he said that if he learned to read music, he might not be able to write as well," Baker explained, adding that his mistrust of the Fab Four went back to the band's early days. "We used to say about the Beatles in 1963: 'They didn't know a hatchet from a crotchet.' A crotchet is what we call a quarter note."

Four years later, Baker offered up some backhanded compliments for the Beatles. "John Lennon was the best musician in the Beatles by a country mile," Baker told Classic Rock. "But George Martin was the Beatles," he said of the band's producer. "Without him they'd have been nowhere."

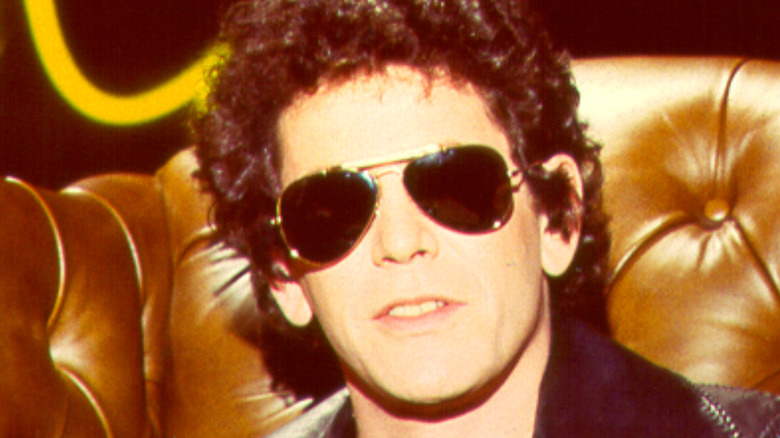

Lou Reed

Championed by modern art icon Andy Warhol and fronted by singer-songwriter Lou Reed, the Velvet Underground presented a stark contrast to the music of the Beatles. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, their self-titled album and follow-up "Nico" presented droning, atonal, and deliberately unconventional soundscapes about drug users and others living on the fringe of society.

Presaging the rise of punk and indie rock, the Velvet Underground didn't sound much like any other rock band that came before it or its contemporaries, and that was probably by design. Reed didn't like the music being made by other '60s rock bands. "I just thought the other stuff couldn't even come up to our ankles," he said in record executive Joe Smith's Blank on Blank series in 1987. "They were just painfully stupid and pretentious." Reed reserved some special vitriol for the Beatles. "I never liked the Beatles. I thought they were garbage. If you said, 'Who did you like?' I liked nobody."

Pete Townshend

Like the Beatles, the Who came out of the British rock scene of the mid-1960s. Unlike the Beatles, the Who were loud, heavy, and aggressive, giving voice to the agitated youth of the era. Pete Townshend wrote the majority of the band's early work and played lead guitar, known for his distinctive "windmill" strumming technique.

On a 1966 episode of the youth-centric BBC talk show "A Whole Scene Going," Townshend lamented what he saw as a general lack of quality in popular music at the time. He specifically called out the Beatles for their lack of greatness, particularly as it pertained to their manipulation of recording technology. Townshend discussed how he and Who bassist John Entwistle had just been listening to a Beatles LP in the stereo format. "The voices come out one side and the backing track comes out of the other," Townshend explained. That allowed Townshend to isolate the vocals as well as the instrumentals, and neither did much for him. "And when you're actually hearing the backing tracks of the Beatles without their voices they're flipping lousy."

Todd Rundgren

Often working on the cutting edge and just outside of the mainstream, Todd Rundgren made layered, dreamy, and experimental pop-rock for himself, his band Utopia, and as a producer and collaborator for acts including Meat Loaf, the Tubes, and the New York Dolls. He's probably best known for his '70s radio hits like "I Saw the Light," "Hello, It's Me," and "Bang on the Drum All Day."

In a 1974 interview with British music magazine Melody Maker in which he promoted his "Todd" LP, Rundgren veered off topic to discuss the solo career of John Lennon. He had scored some hits with progressive and socially conscious singles like "Imagine," "Power to the People," and "Give Peace a Chance," none of which moved, charmed, or convinced Rundgren. "John Lennon ain't no revolutionary. He's a f***ing idiot, man. Shouting about revolution and acting like an a**. It just makes people feel comfortable," Rundgren proclaimed (via Far Out). "All he really wants to do is get attention for himself, and if revolution gets him that attention, he'll get attention through revolution." Rundgren later admitted that Lennon is a culturally significant figure, "But so was Richard Nixon," he quipped.

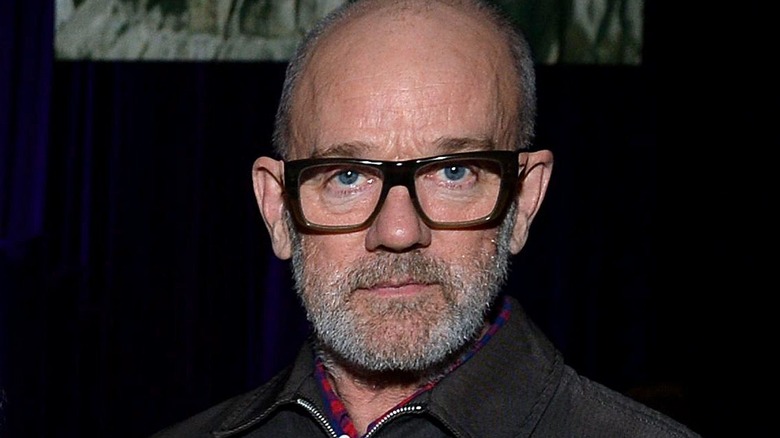

Michael Stipe

Two decades after the Beatles launched the British Invasion in the '60s, R.E.M. gave rise to alternative rock, or "college rock," as it was known at the time. Emerging from the university city of Athens, Georgia, R.E.M. combined jangly guitars with poetic lyrics sung passionately. The latter was the work of frontman and lead singer Michael Stipe, who'd head up R.E.M. for 30 years, making smash hits and radio staples out of "Stand," "The One I Love," "Everybody Hurts," and "Losing My Religion."

It's not as if Stipe outright hated the Beatles — they merely left him feeling nothing. "The Beatles were elevator music in my lifetime," Stipe told Rolling Stone in 1992, adding that the 1968 Ohio Express bubblegum pop hit, "Yummy Yummy Yummy," "had more impact on me." About three decades later, Stipe clarified his remarks but doubled down on his ambivalence toward the Fab Four. "I'm not really a Beatles fan, though. I acknowledge their genius, but I'm just not the generation that grew up with them," Stipe told Pitchfork in 2021. "It's not something I'm personally drawn to, and that's gotten me into a lot of trouble in the past."

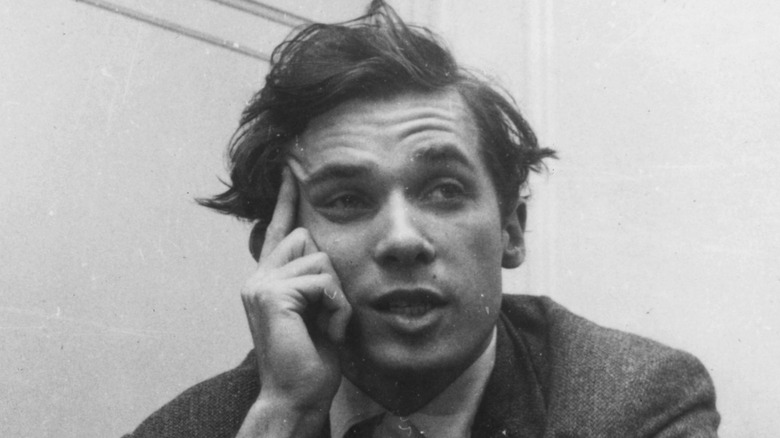

Glenn Gould

A classical pianist who packed concert halls around the world, Canadian musician Glenn Gould quit performing in 1964 to focus entirely on recording music. He went on to release 80 albums of avant-garde-leaning instrumental music, taking a particular interest in reinterpreting the compositions of Bach.

In a 1974 interview series with Rolling Stone, collected in "Conversations with Glenn Gould," Gould discussed contemporary pop music figures. A classical musician who was highly literate in musical theory, he wasn't much impressed by the Beatles. Gould called out what he thought were "ultrasimplistic notions" and a lot of filler in their music. "After all of the pretension has been cut away... what you really have left is three chords," Gould said. "Now, if what you want is an extended exercise in how to mangle three chords, then obviously the Beatles are for you." The pianist didn't think much of their lyrics, either. "I mean, 'I Want to Hold Your Hand' — you can understand that; 'Let it Be" — you can understand that. And almost everything in between is sort of way down there, buried under piles of garbage, of instrumental garbage."

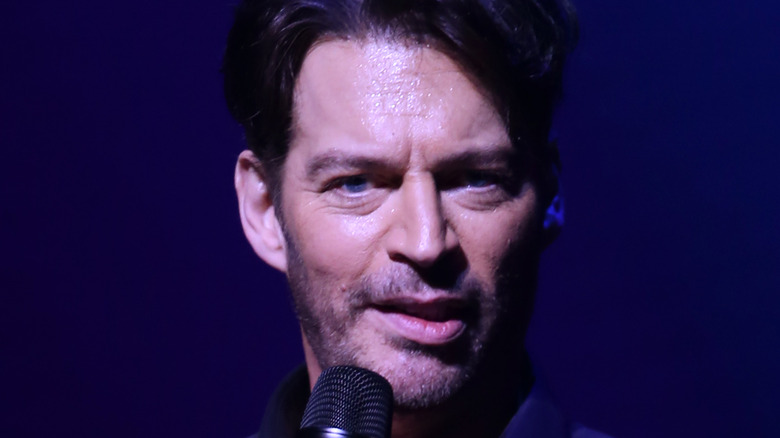

Harry Connick Jr.

The son of a New Orleans politician, Harry Connick Jr. grew up surrounded by jazz and was a locally famous piano-playing wunderkind before he found mainstream success as an adult. Later an actor and a talk show host, Connick broke out big with a collection of standards that served as the soundtrack for the 1989 romantic comedy "When Harry Met Sally..." which positioned him as a jazzy crooner who accompanied himself on the piano and sometimes led an old-fashioned big band.

Connick overwhelmingly favored pre-rock sounds, espousing the virtues of old-fashioned crooners like Frank Sinatra, and conversely, criticizing bands like the Beatles who didn't do what Sinatra and other singers did. "I just want to touch him. I just want to say, 'Mr. Sinatra, you're the king,'" Connick told USA Weekend in 1990 (via the Santa Cruz Sentinel). As for the Beatles, Connick said, "That music is for second-graders."

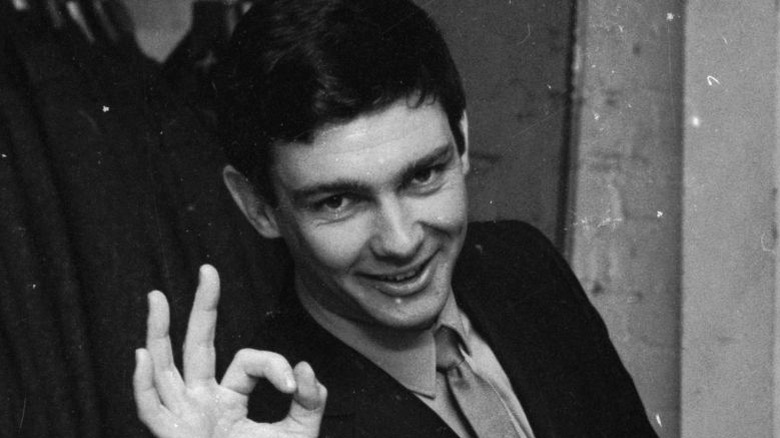

Len Barry

The Philadelphia-based band the Dovells were American contemporaries of the Beatles. In the mid-1960s, they landed several songs near the top of the pop chart, including "You Can't Sit Down," "The Bristol Stomp," and "1-2-3." The Dovells were as much of a soul act as they were a rock band, owing to the distinctive vocals of lead singer Len Barry, who'd launch a solo career and take the song "1-2-3" to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100.

In 1966, Barry declared to Hit Parader that he was done associating with and performing alongside long-haired rock 'n' roll bands. "It isn't only that they look like a collection of tramps, they act that way and it's the way they really are," Barry said. "They're appealing to the lowest possible common denominator in their appearance, performance, and in some cases in their material as well."

Barry specifically had some choice words for the Beatles, who he thought had a bad work ethic and bad attitude. "I enjoy their records but I think that they're probably one of the worst in-person acts I've ever seen. They make a joke out of the kids who love them. They ridicule the very people who took them out of the gutter and made them stars."

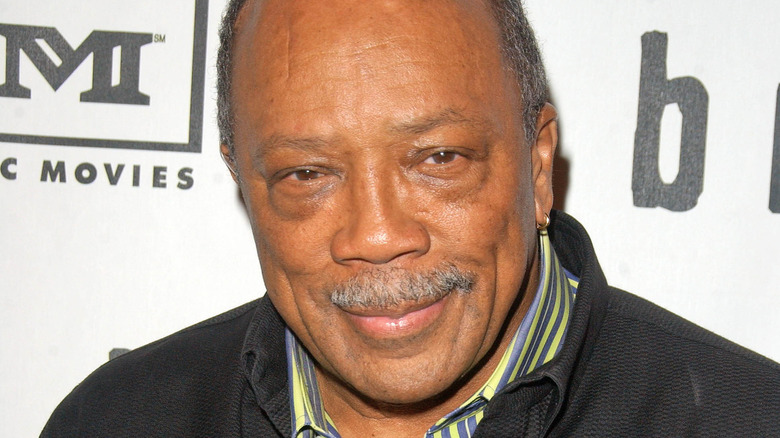

Quincy Jones

As a trumpet player, producer, arranger, and composer, Quincy Jones has been working behind the scenes in the recording industry since the 1950s. He'd already well established himself by the time the Beatles broke in the U.S. in the mid-1960s. And when Beatlemania hit and captivated millions of new fans, Jones wasn't among them. "They were the worst musicians in the world. They were no-playing motherf***ers," Jones recalled to Vulture in 2018, referring to what he thought was their poor musicianship. "Paul was the worst bass player I ever heard. And Ringo? Don't even talk about it."

Jones recalled one time sitting in on a studio session with Ringo Starr, and the drummer couldn't get a small portion of music correct after three hours of trying. He and producer George Martin dismissed Starr and brought in jazz drummer Ronnie Verrell, who knocked out the tricky part in 15 minutes. About the only classic rock band Jones would admit to enjoying was Eric Clapton's late '60s supergroup Cream. "Yeah, they could play," Jones said.